In the playpen that is nonverbal marks, the game is all about whether registrants can jump the hurdle between two opposing classifications—product packaging and product configuration.

Conceived to decide whether nonverbal marks merit trademark protection, nonverbal marks fall into three categories: product packaging (also known as trade dress) which is capable of inherent distinctiveness; product configuration (also known as product design) which is capable of acquired distinctiveness; and tertium quid.

In doing so, courts have tried to create a framework that keeps sellers from being able to secure marks that add to a piece’s commercial appeal, like an attractive color, or a pleasing shape of a product, without first having to prove that consumers see the thing as a source identifier.

By this logic, the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) held that a monster truck entertainer could trademark their truck’s décor as inherently distinctive product packaging in In re Frankish Enterprises Ltd., 113 U.S.P.Q.2D (BNA) 1964 (TTAB 2015). Monster truck fans, TTAB reasoned, pay for the privilege of watching massive trucks crush things and hurdle through the air. Whether the truck itself is painted to look like a triceratops, it reasoned, is secondary to the automotive carnage for monster truck rally enthusiasts.

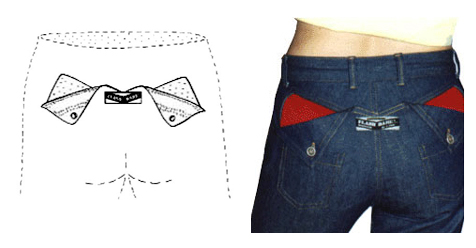

On the other hand, the Federal Circuit ruled that the cutouts in a pair of jeans at issue in In re Slokevage were only product configuration, requiring costly proof of acquired distinctiveness in the marketplace. Quoting Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Brothers, Inc., the court reasoned that product design is not inherently distinctive because its inclusion makes the “product itself more useful or more appealing.”

It is on this spectrum that nonverbal mark disputes have been played for decades. Is a nonverbal mark separate enough from the product’s intrinsic usefulness or appeal that the trademark applicant doesn’t need to prove that it has source-designating meaning?

But what if I told you that the game was not so two-dimensional?

That there is a way to make it impossible for a nonverbal mark to ever acquire distinctiveness? That you could submit a product configuration mark to TTAB and not only get denied registration, but that they could tell you that you can never reapply? Even with proven secondary meaning? And then what if I told you that the practice has had precedent since 2013?

In re Lululemon Athletica Canada, Inc., a 2013 TTAB case, does just that. In Lululemon, the athleisure juggernaut sought registration for “a single line in a wave design that is applied to the front of a garment” as pictured below. In response, TTAB did not merely deny Lululemon registration. They deemed the mark “merely as ornamentation”—a design that is “rather simple” “piping” that is not stylized enough that the public would understand it to be more than an ornamental flourish.

It seems like TTAB made a presumption about how relevant consumers will perceive a product here which makes a dramatic encroachment on product configuration doctrine. How a mark is perceived by the relevant consumer base is a key tenet of trademark law, and applicants should be allowed the opportunity to prove their mark’s value as a source designator through secondary meaning.

Should it not be considered that I, a consumer in Lululemon’s target demographic who begrudgingly loves his Lululemon Surge Warm Half-Zip and Surge Shorts (plural!), understood this ornamentation to be a stylized version of the Lululemon logo? Why shouldn’t the brand be allowed at least the opportunity to prove acquired distinctiveness as product configuration?

And why, when the curved panel of an air conditioning unit could be considered a registrable product configuration, is Lululemon any different?

Oddly, this “mere ornamentation” theory has not been followed in the past nine years. In the meantime, the product packaging-product configuration spectrum has continued as the lingua franca of nonverbal mark disputes. This leaves us with a few takeaways. Lululemon is still good law. And we need to ask ourselves why it has not had more of an impact. That being the case, is Lululemon an iceberg-in-waiting, and could the canny trademark lawyer use the precedent to upend nonverbal marks doctrine as we know it?

… [Trackback]

[…] Information on that Topic: jipel.law.nyu.edu/can-mere-ornamentation-blow-up-product-configuration/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More to that Topic: jipel.law.nyu.edu/can-mere-ornamentation-blow-up-product-configuration/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Information here to that Topic: jipel.law.nyu.edu/can-mere-ornamentation-blow-up-product-configuration/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Information here to that Topic: jipel.law.nyu.edu/can-mere-ornamentation-blow-up-product-configuration/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info on that Topic: jipel.law.nyu.edu/can-mere-ornamentation-blow-up-product-configuration/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 10918 additional Info on that Topic: jipel.law.nyu.edu/can-mere-ornamentation-blow-up-product-configuration/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here on that Topic: jipel.law.nyu.edu/can-mere-ornamentation-blow-up-product-configuration/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info on that Topic: jipel.law.nyu.edu/can-mere-ornamentation-blow-up-product-configuration/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you can find 72306 additional Info on that Topic: jipel.law.nyu.edu/can-mere-ornamentation-blow-up-product-configuration/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information on that Topic: jipel.law.nyu.edu/can-mere-ornamentation-blow-up-product-configuration/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you can find 40897 additional Info on that Topic: jipel.law.nyu.edu/can-mere-ornamentation-blow-up-product-configuration/ […]