By Roya Ghafele*

Download a PDF version of this article here

I. The New Paradigms of the Internet of Things

The next wave of internet usage will disrupt a host of

different industries, while at the same time opening up so far unknown

opportunities to those ready to seize them. Devices and components with an

internet address will be joined to each other allowing for large-scale

communication embedded in gigantic sensing systems.[1] In this sense, the

Internet of Things (IoT) can be understood as a means

to connect objects, machines and humans in large-scale communication networks.[2] The IoT merges physical and virtual worlds by interconnecting

people and objects through communication networks, sending status updates, and

reporting on the surrounding environment. Applications will become more

sophisticated, allowing for the emergence of services and product offerings

that are beyond our imagination: IoT based toys will

accompany children from early age until adulthood, IoT

driven medical devices will save the lives of those suffering from a sudden

stroke, and clothing with IoT technology built in

will allow everything from our shirts to our shoes to customize according to

daily fashion trends. Smart homes, smart cities, and even smart countries will

become the norm; reducing energy wastage to a minimum. The commercial

opportunities associated with the IoT will be

substantial. Markets will expand into areas we have not even conceived of,

thereby creating new jobs and fostering further competition between the various

regions of the world.

Against this background, the European Union has recognized

the need to identify a governance framework that will enable it to take

advantage of the promising opportunities associated with the IoT, while mitigating risks and adverse effects to the best

extent possible. An important aspect of a European IoT

strategy consists of adequately addressing the interplay between competition

and intellectual property law. Consequently, the European Commission itself

considers it necessary to formulate policy guidelines on fair, reasonable, and

non-discriminatory (FRAND) licensing. In order to accomplish this, the European

Commission (E.C.) launched a series of stakeholder consultations, workshops and

published two in-depth reports addressing the potentially anticompetitive

effects that standard essential patents could have for the Internet of Things.[3] With the goal

of offering further clarity on the licensing conditions for patents that read

on standards, the E.C. issued guidelines on FRAND licensing[4] on the 29th of November

2017.[5] While these guidelines are non-binding,

the E.C. will nonetheless take advantage of soft law mechanisms so to offer a

transparent framework for FRAND licensing. This appears justified given the

major patent wars[6] that the

licensing of standard essential patents triggered in the telecommunications

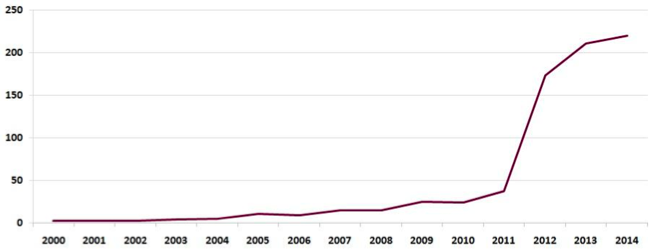

sector. For a quantitative analysis of the imminent rise in patent litigation

in the area of speech recognition, an area closely related to IoT, see for example the below analysis by iRunway; showing a sharp increase in patent litigation

since 2011.[7]

Figure

1: Patent Litigation Trend in Speech Recognition Domain (Source: iRunway analysis based on patent data from USPTO and

litigation data from RPX)

(Source: iRunway analysis based on patent data from USPTO and litigation data from RPX)

While it is laudable that the E.C. is taking ownership of a

key policy area that will make or break the success of the IoT,

it is regrettable that the process preceding policy formulation has been

primarily driven by interaction with large corporations and industry

associations having significant experience with FRAND licensing. The views,

experiences and opinions of European young innovative companies, YICs, are

largely missing from the policy development process. Given that young

innovative companies are seeking to advance the IoT,

the European Commission is hence likely to have missed out on input from those

companies, who are doing their best to move the IoT

forward. To fill this gap, this study undertook a series of thirty in-depth

interviews with young innovative companies active in

the European IoT space. In doing so, it hopes to

counter policy formulation that lacks grass roots linkages and takes

insufficient consideration of the needs of YICs. In doing so, this study is

pleased to report that the suggestions made hereby were reflected in the E.C.

Guidelines on FRAND.[8]

The study is structured in two main parts. The first part is

dedicated to discussing key features of the IoT from

an IP and competition policy perspective. The second part presents the findings

from the field study undertaken in the summer of 2016. It concludes by urging

policy makers to include young innovative companies in the policy process as it

finds that there is quite a significant gap between the theoretical

conceptualisation of the topic and the practical experiences of YICs.

A. Defining

the Internet of Things

Identifying a working definition for the Internet of Things

is complicated by the fact that the IoT is an

umbrella term encapsulating a variety of different technologies. The IoT has been described as “a concept that interconnects

uniquely identifiable embedded computing devices, expected to offer

Human-to-Machine (H2M) communication replacing the existing model of Machine-to-Machine

communication.”[9]

It has also been labelled as “[I]nternet-enabled

applications based on physical objects and the environment seamlessly

integrating into the information network.”[10] More narrowly, the OECD

defined the IoT as “Machine to Machine communication

(M2M)”[11] and the

European Commission describes the IoT simply as

something that “merges physical and virtual worlds… where objects and people

are interconnected through communication networks and report about their status

and/or the surrounding environment.”[12] All of these definitions

are fairly vague and it is probably for that reason that they encapsulate the

gist of the IoT so well. The IoT

constitutes a high growth business opportunity as its application is vast and

it bears the potential to transform virtually every sector of the economy. In

current IoT markets, it is not yet clear what type of

business models will succeed and who will emerge as a market leader. As such,

the IoT space has been described as being quite

dispersed and driven to a large extent by small early stage companies.[13]

II. The Internet of Things is exposed to Network Effects

…

The IoT is a network-based

technology, which thrives on multilateral exchange. Similar to

telecommunications networks, it constitutes an interconnected eco-system. Such systems

can be associated with “network effects.” Network effects are “defined as a

change in the benefit, or surplus, that an agent derives from a good when the

number of other agents consuming the same kind of good changes.”[14] The more

the peculiar software solution of one firm becomes adopted, the more it will

benefit this specific firm, making it more difficult for new entrants to see

their technological solutions adopted in the market; even if they are of higher

technological quality. Network effects enable large-scale access to an

interoperable software solution, whose value thrives with additional adoption.[15] The more

the IoT solution is in use, the more it becomes known

and even more additional users will be attracted to it. At the same time,

existing users are less and less inclined to switch to another service

provider.[16] Some

scholars consequently associate networks with “increasing returns” to “path

dependence.”[17] The

initial success of one specific IoT solution is often

owed to small, random events; yet once it establishes a strong position in the

market, it will remain in use, even if better technological solutions are

identified. This is because users cannot afford to switch, as they would have

to give up the interconnectivity provided by the existing network. Thus the overall effect is to discourage technological innovations

as incumbents entrench themselves through network size and technological

compatibility rather than technological sophistication.[18]

Once critical mass is reached, usage of the service will

grow quasi-automatically and this comes often to the detriment of other service

offerings.[19]

Furthermore, critical mass allows incumbents to gain significant cost

advantages over new entrants who undoubtedly will face significant upfront

costs because IoT solutions are complex to design,

costly to deliver to the market, and accessibility to the needed know-how is

often protected through patents or trade secrets. In addition, incumbents will

be in a position to offer complementary services, extensions, add-ons and

customer support to further strengthen their dominance in the market, making it

more difficult for new entrants. Hence, network effects can reasonably be

understood as the “tendency for that

which is ahead to get further ahead, for that which loses advantage to lose

further advantage.”[20]

Consequently, network effects can distort competition and adversely affect

consumers.

III. Which can trigger Anticompetitive Licensing

Behaviour

Adverse implications of network effects can be even more

pronounced if interoperability is achieved through standardization and market

participants leverage patents to protect their inventions. Standards are

dynamic, in the sense that their main function is to ensure a collaborative

technology development. Standards do evolve over time. However, the status quo

of a technological solution does exist for a given period of time, at least

until a new standard is adopted by the market that addresses the same

technological challenge.

Patent protections on theses standards,

particularly if held by a wide range of market participants, can incite anticompetitive

behaviour. To mitigate the kind anticompetitive licensing behaviour that

standard essential patents can trigger, the FRAND agreement was introduced. The

“FRAND promise is construed according

to its core function as an irrevocable waiver of extraordinary remedies” and

hence seeks to counterbalance the exclusionary aspects of patent law.[21] Because of the FRAND or RAND (in the

U.S.A.) commitment, companies are obliged to license patents on a standard on

fair (Europe only), reasonable and non-discriminatory terms, following the IP

policies of the relevant standard setting organizations. Hence, the FRAND

concept seeks to offer a governance framework for the licensing of standard

essential patents. Because these patents can accrue market power to their owner

and hence potentially provoke anticompetitive licensing behaviour, it is

believed that standard essential patents are warranted different licensing

pathway than other patents — namely, they must be licensed in a way that

comports with the FRAND framework. Exactly how such a FRAND framework should be

applied, and whether the scope of the application should be narrow or broad, is

currently subject to international IP policy formulation. If the FRAND

agreement offers adequate means to mitigate against risks associated with

widely dispersed patent ownership, that will also deserve further policy

attention.

A new entrant may need to hack through a host of patents

held by many different IP owners, which can lead to an undesired anti-commons

effect, whereby existing patents stifle rather than promote innovation and the

very purpose of the patent system is undermined.[22] While it is important to

note that the IoT does not yet dispose of any

prominent standards, nor depend on any particular technology protected through

patents, it is quite unlikely that this will remain that way. If the IoT is to evolve from its current state of infancy to a

more mature technology field, it will be necessary to establish widely used

standards. At this point, contributors to those standards will undoubtedly want

to leverage their IP for licensing, sales purposes or blocking third party

entry. Although these may be legitimate usages of IP, the licensing of standard

essential patents has also been associated with an undesired behaviour known as “holdup.”

The impact of holdup can be particularly pronounced where

firms benefit from first mover advantage or where firms have the necessary

innovation capacity to capture the patent landscape. It is, however, incorrect

to assume that patent holdup would only be an issue concerning “important”

patent owners. In fact, each and every standard essential patent owner (SEP

owner) could theoretically engage in holdup because its position as a

gatekeeper to the standard allows him or her to do so. It is alleged that these

patent holders — having claimed an important position in the patent landscape —

can charge abnormally high licensing rates to standard essential patent licensees.[23]

By charging these high licencing

rates, the patent holders are engaging in the practice of what is commonly

called patent holdup. For instance, it has been stated that the holdup problem

is particularly severe with mobile telecoms standards because the standards

that are adopted are used for a long time and the costs that are associated

with switching to an alternative standard are high.[24] Further it has been argued

that standards holdup is both a private problem facing industry participants

and a public policy problem. Privately, those who will implement the standard

(notably manufacturers of standard-compliant equipment) do not want to be

overcharged by patent holders. But standards hold-up is also a public policy

concern because downstream consumers are harmed when excessive royalties are

passed on to them.[25] Given

that the IoT can be associated with network effects,

it is likely that such adverse effects could occur within the context of the IoT as well.

Adverse licensing behaviour

could also occur if licensees stall payment, refuse a licensing agreement all

together, or take a license below the fair rate. Such holdout constitutes an

equally problematic market practice as it leads to free riding problems

associated with technology used. Licensees may also simply engage in a series

of offers and counteroffers to further stall negotiations. Such strategic

behaviour can erode the incentive to invest in R&D. Both patent holdup[26] and holdout[27] are

possible in the IoT context and both can constitute

undesired strategic behaviour.[28]

IV. . . . that can particularly affect Young Innovative

Companies

Young innovative companies (YICs) can be particularly

vulnerable to adverse licensing behaviour. YICs, which have come to be

understood as small, young and highly engaged in innovation, aim “to exploit a

newly found concept, stimulating in that way technological change, which is an

important determinant of long run productivity.”[29] While it would appear that

the very process that drives YICs would quite naturally be associated with

patent protection, it has been observed that micro enterprises and SME lack IP

awareness.[30]

YICs’ fear above all are the costs associated with patent

protection and patent enforcement. From the perspective of YICs, IP is primarily

a cost factor that diverts time and attention away from doing business. Studies

undertaken by the UKIPO,[31] the IPR

Helpdesk of the European Commission,[32] as well as WIPO[33] show that

such firms associate IP protection with a tedious, laborious and time-consuming

endeavour that offers only moderate support to business because costs

associated with enforcement are often unaffordable. For the same reasons, these

firms tend to be reluctant to enforce their own patents against infringers,

leaving this group of firms with questionable patent proposition. This has led

several observers to the conclusion that “deterred by high costs and

complicated procedures, YICs tends to lack the necessary skills to take any

particular advantage of the patent system.”[34] The UK Government’s

Hargreaves Review “IP and Growth,” further highlighted that strategic advice

would be needed to help fill this gap stating that “many SMEs have only limited

knowledge of IP and the impact it may have on their businesses; they lack

strategic, commercially based IP advice; have difficulties identifying the

right source of advice and IP management is made impossible due to too high

costs.”[35] Hence,

cost and time constraints tend to discourage YICs from taking ownership of the

patent system. With respect to the particular challenges associated with

standard essential patents, it is very likely that the overarching lack of IP

competence will overshadow any potential experiences there may be with standard

essential patents. Arguably, the lack of IP skills will make YICs more prone to

unreasonable licensing requests, while at the same time making them more likely

to inadequately respond to licensing requests themselves. Hence, lack of

knowledge will risk exposing YICs to anticompetitive IP requests, while at the

same time making them more likely to stall licensing engagement payments.

V. Methodology

Is there a gap between the way European policy makers and

YICs are conceptualising the role of IP in the IoT?

To gain further insight into that question, a series of thirty-one in-depth

interviews were undertaken with YICs during the course of 2016. In addition,

four contextual interviews were carried out. Interviewees were asked to reply

to a set of open ended questions, allowing them to discuss their experiences

with patents and standards, present their licensing practices and the extent to

which they were (if at all) exposed to licensing requests. They were also asked

if they feared patent wars similar to those in telecom could occur in the IoT space and what they would expect the European policy

maker to do to counter potentially anticompetitive usage of IP, while helping

them to take advantage of standards and patents. The issue of software patents

was deliberately excluded from the conversations as this was subject to

historical policy formulation and not that of current policy thinking. Given

the stance taken on software patents in the E.U., the market participants

interviewed here would simply not have been in a position to comment on their

experience with software patents in the E.U.[36]

The technique applied is known in social sciences as a “semi

structured interviewing” process.[37] The

techniques give the interviewees space to express their own perspectives and

mitigates against biased research results. This approach is somewhat comparable

to a study based on focus groups. Such a qualitative research method was

considered suitable as it allows us to theorize about what public policy

formulation could look like in an emerging field of technology, where policy

guidelines are yet to be identified. In addition, this specific research

approach offers the necessary insights for a bottom-up approach to public

policy formulation.

The target group was identified via LinkedIn. The firms

interviewed usually had no specialized lawyer dedicated to IP issues, so the

most senior person in the company was interviewed. This was usually the Chief

Executive Office, Chief Technology Officer, Chief Operating Office or sometimes

one of the investors in the firm. The vast majority of the firms interviewed

were early stage firms or start-ups. Only Italian firm ‘S.’ has been acquired

by a major technology company. In addition to interviewing a core group of

young innovative companies, we also undertook contextual interviews with a

financial analyst, a few management consultants specialized in the IoT space, as well as a patent analyst with whom we

discussed patent landscapes. Of the 350 people we reached out to, we obtained

thirty-five interviews — yielding a response rate of 10%. A sample of

thirty-one in-depth interviews with Young Innovative Companies and four

contextual interviews is usually considered sufficient to provide meaningful

insights.[38] It is

recognized, however, that such a qualitative research method, cannot offer

“hard facts,” but only views, opinions and impressions.[39] Yet, it is precisely this

web of views and opinions that is key in politics. Language is a constitutive

element of politics, shedding light on the language of those otherwise

marginalized in the political process, which is conducive towards the

democratic process. The FRAND debate forms no exception to that.

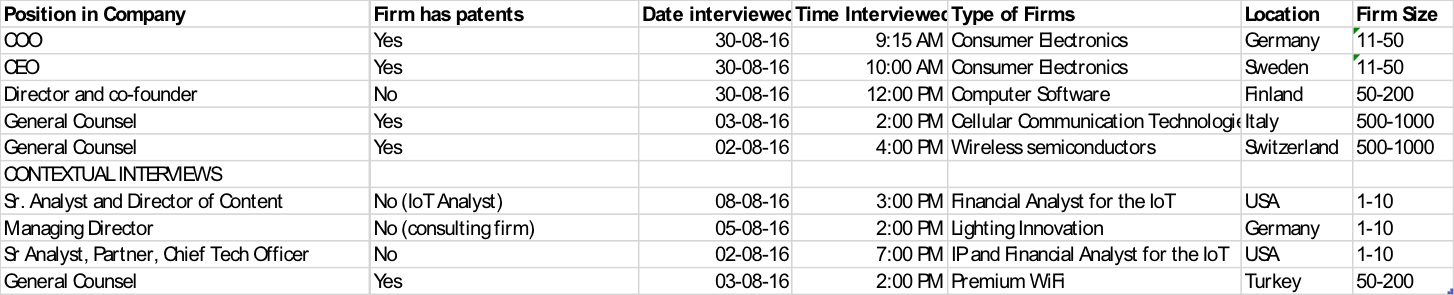

Table 1 offers an anonymized overview of the interview

process. In order to shield the interviewees from potential exposure to patent assertion

entities, it was decided not to disclose their identities publicly. The

detailed transcripts of the interviews are available only in my private

archive.[40]

A. Trends in Internet of Things

Markets

Of the 31 firms we interviewed, no two firms had the same

business proposition or sought to apply the IoT in

the same manner. The firms interviewed seek to apply the IoT

in areas as vast as fashion, toys, lighting, smart cities, health care, automotive

and even social housing. In regards to technology,

cloud services, big data, and platforms appear key to many of these early stage

businesses. Social Innovation and lean management were other concepts, which

were often combined with the usage of the IoT. It was

surprising to hear that the majority of the firms interviewed had fairly little

start-up capital. In many instances, EU grants were considered too complicated

to obtain and if obtained at all, then regional funds were used. Some sought

funding in the U.S., as they thought there was more capital available there.

Interviewees confirmed that the IoT

was a mesmerizing and also somewhat confusing term: “The IoT

is a buzz word just like big data, the market is still very early stage, but I

have a feeling that we may be not far away from a break-through in the market.”

(K.) This makes it quite difficult to describe the state of the market or

capture industry trends. “The IoT market is still in

search for adequate applications . . . many solutions are quite simple and they

could just as well function without the IoT.” (J.) Overall,

interviewees agreed that the market is still very early stage, with many firms

still looking for an adequate business model. “The main problem is how to

establish the business model around the technology . . . the market is still in

a trial and error stage.” (M.) Yet, in spite of the various uncertainties

surrounding the IoT, it is seen as a “mega trend”

with substantial growth opportunities: “The Iot? I

think it is going to happen . . . in up to five years we will be able to talk

about billions.” (I.)

Overall, interviewees were sceptical

about the prospects for European markets. According to them, the markets for IoT will take off in the U.S. and Europe will eventually

follow. “I think we are behind the US with its Silicon Valley and its big tech

firms that lead the tech industry.” (A.) “The IoT

market in Europe is imagined.” (L.) “The IoT market

is something we believe in, but it is not yet established in Europe.” (G.) This

should be a wake-up call for policy makers in the EU and set them thinking

about what can be done to promote the IoT in Europe.

B. Standardization,

Patents and Standard Essential Patents Experiences

The YICs interviewed were not able to formulate particularly

nuanced views on SEPs, standards, patents or licensing markets. With respect to

standard essential patents they were entirely ignorant on the topic and were

also not involved in the regulation processes of any of the standardisation

organizations. Their experience with patents mainly pertained to difficulties

associated with obtaining patents, facing high filing costs, feeling

overwhelmed by legal costs and finding information on prior art. “Our patent

attorney is ripping us off . . . and we don’t even know if it is really worth

it.” (S.)

Alarmingly, many YICs we talked to even doubted that the

patent system mattered at all for them. “The technology in this area is moving

so fast that by the time you have the patent the technology is outdated. I am

not sure patents are really helpful, it is only expensive for a small firm . .

.” (S.) It was lead-time advantage

and open source software that mattered, rather than proprietary innovation. “When

you are in the Savanna and you don’t know if you are the antelope or the lion,

what do you do? You run! With IP it is the same. We

care about first mover advantage. The IP is so hard to enforce and so costly

that we feel we are better off without it.” (F.) Equally, defensive mechanisms associated with IP were entirely

ignored. The reason given was that a defence would be too expensive. There was heavy doubt that the

patents had a business proposition at all. Also, there was a sense that the

value proposition of the firm was to deliver customer solutions or products and

there, so many agreed, IP had not really any particular meaning for them. It

was products they offered that were valuable, not IP protection. “We have filed a few patents in the US

and through the PCT, but we have no business usage for them.” (M.) These

findings are commensurate with what

has been reported in the literature and underline the need to combine overall

IP measures geared towards YICs with the overarching SEPs debate.

Some of the firms we interviewed went as far as to state

their discontent with the patent system openly. “In general

we don’t like patents . . . we think they are very bad . . . the original idea

of the patent was to protect an invention, but in the software space patents have

been abused for a long time . . . just look at the patent trolls.” (W.) Patents

were also mentioned as a means to slow down businesses and as leaving YICs

exposed to threats of litigation. “I don’t like the IP part . . . patents slow

things down . . . I would prefer never to file patents. I believe in building a

lot of brand capital.” (H.) Even those

firms who considered developing a patent strategy, found that costs associated

with patent ownership prevented them from taking advantage of the patent

system. For example, a Partner at V. presented plans for a patent strategy, but

was not able to execute it because of cost constraints. “Patents are expensive

and there is no point in patenting if you don’t have the money to defend your

patents . . . [s]o, we are waiting.” (H.)

C. Licensing

Experiences in the Internet of Things Spac

The YIC’s knowledge of European patent ameliorating efforts

was no better. When asked about FRAND licensing, they were also completely

uninformed and key terms had to be explained first. Following that, firms

generally did not feel competent enough to comment. Similarly, the consequences

they could be facing in case of patent infringement were unknown to them.

The YICs talked to were not involved in patent licensing and

they generally denied having been exposed to patent licensing. If, at all, it

was copyright licensing they used. This was however called by all the interviewees

“software licensing,” maybe because they were not very IP savvy. This was seen

as a fairly straightforward process and nobody found there was a need to

discuss this at length. “Software licensing is our business strategy, not

patent licensing… our business is to sell the usage of the platform.” (S.) However, interviewees were not exactly

sure what the question meant. Only two firms had experience with patent

licensing. N. told us that he had been exposed to licensing in another firm he

worked for and there they used the out-licensing of patents as a means to

manage competition. “Licensing no, not in this firm no, but in another firm, we

used patent law suits to slow down our competitors.” (B.) Furthermore, the IoT sector was not

considered an industry where patent licenses were needed. “In our industry nobody would want to take a license.” (T.)

The role of patents was however seen in a different light by

more established firms. Here, costs mattered less and measures such as

licensing did play a role. Both inbound and outbound licensing was critically

reflected upon. Such firms were also often part of industry associations such

as the IP Europe Alliance[41] or the Fair

Standards Alliance.[42] These

firms are, however, not directly engaged in the IoT

space and hence their input is probably less of relevance here.

Some firms, like the Spanish University spin-off we talked

to, had moved their business from producing parts of an Antenna to pursuing an

active IP licensing program. They found this strategy more lucrative. (I.)

Similarly, the CEO of a Danish software firm confirmed that his company is “now

slowly moving from a mere defensive approach to IP to a more aggressive way of

managing its IP.” In particular, this firm is interested in establishing a

systematic licensing program targeting potential infringers.

However, even those who have an active licensing program in

place do not find it an easy business. For example, one Danish inventor explained

that it took him nearly ten years to obtain a patent family and that he also

attracted significant investments so to obtain licensing revenues from firms

that infringed on his patents, but he overall found it to be a very long,

complicated and so far not particularly lucrative

process. He concluded that “the patent system was a bit ridiculous . . . and

that the return on investments in patents is not very good . . . you always

have to use a lawyer, but these guys [the firms he was trying to get a license

from], they shut down their business and then they open up a new one and you

get to start all over again with suing them . . .” (J.) The CTO of the spin-out

from the Spanish University was the only one we talked to who felt that the

patents the firm had were truly beneficial to their business. His only concern

was that licensees can deploy delay tactics and that can become difficult.

Otherwise he considered patents an important instrument of monetization.

Additionally, the senior

representatives of three SMEs were interviewed. These firms had been approached

for taking a license but all of them found the process unhelpful. One firm, for

example, criticised that licensing requests were not supported by adequate

documentation. Many licensors do not even send claim charts or send them only

very late, in an effort to pass on costs from licensor to the licensee. Also,

they complained it was very common to receive unrealistically short deadlines

for a legally binding reply. This situation is made even more complicated as it

is a lengthy and costly procedure to determine whether some patents claimed to

be standard essential, really are standard essential: “what is a standard essential patent and what not is essentially

gut feeling.” (L.) According to them, it is also very costly and time consuming

to negotiate licensing rates. Many times they are forced

to accept a license rate simply because costs to counter the argument would be

too high. They argued that it is also difficult to determine what an adequate

royalty rate is in the absence of an adequately defined framework for licensing

standard essential patents.

D. The Threat of Patent Wars and

Lack of Defence Mechanisms

There was a general sense among interviewees that patent

wars as seen in the telecom space could repeat themselves in the IoT space. “Definitely, definitely . . . I think the IoT space is a classic example . . . I would not be

surprised if in 2019/2020 we would see these things.” (R.) The only reason, in

their view, why this had not happened yet, was because the IoT

sector was still too immature. Still, the potential emergence of patent wars is

seen in a negative light. Once more, interviewees underlined that the patent

system is not equally accessible to small and big players: “it is a downward

spinning circle. The more cases you have, the more people will shy away from

the IoT because patent litigation is really expensive

. . . and then the IoT will only be for the super big

ones.” (B.) Nobody expected such patent confrontations to occur any time soon,

though: “Maybe in the future, when the markets are more mature, but I don’t

think we will see much trolling in the next five years.” (M.)

If patent confrontations were to occur in the IoT space, it is my impression that it would leave most

interviewees unprepared. Some even thought that they could not face any patent

litigation because they had no patents themselves. “Probably it will happen.

But I don’t think about it, but now that you say it . . . yes . . . but since

we don’t have an IP for end customers or big scale use, we will not be attacked

by trolls.” (A.) Some did not even know what the patent war was or thought that

it would not concern them: “What is that? I have never heard of that.” (M.)

YICs also felt quite powerless and that they had little to defend themselves

with against potential litigation. “They are so big and if they want to break

you, they can do that. As a small firm you have no

chance to defend yourself.” (N.) The

only firm in our sample that was not concerned with patent wars was the Spanish

firm that had an active licensing program.

E. What Role

for European Policy?

Many of the firms interviewed felt that the patent system

would require a radical reform. Under a particularly critical light were the

activities of patent assertion entities. “Patents do not help SMEs, the best

would be to get rid of them . . . if that is not possible, then we would need a

complete reform of the patent systems . . .” (S.) For interviewees making the patent system accessible to YICs meant

also making patent enforcement accessible to them. Helping young firms obtain

patents, but leaving them without the necessary financial means to protect

themselves from litigation, was, according to the interviews, not of great

help. “The EC should support smaller firms in enforcement and in a way that

they have the right to have a patent and also a right to enforce it.” (J.) Small firms should somehow have a

chance to defend themselves and the Government should provide some means to do

that. “Any policy reform that helps assure that the patent system is actually

used in a way to promote genuine innovation and not in a predatory way . . . that

one guy invents something great and a patent troll just buys the patent to sue

other people . . . the government should do something to prevent that.” (H.) In

that respect, the E.C. was called upon to identify policies that would counter the

inequalities between parties, something that would enable small players to level

the playing field with large firms. “It would be good to make legislation that

would help avoid situations where big companies use patents as a means to shield

competition from small firms.” (K.) On a more practical level, there could be

more information made available on the role of IP and standards in the context

of the IoT.

Interviewees expressed that educational material, websites,

really anything that would help to get more acquainted with the issues at stake

would be very welcomed and the E.C. should do more in that respect. “What would

help is to allow small firms to learn about patents . . . Are there educational

materials, websites . . . we could get to learn more about IP?” (T.)

There was also a general sense in the community that open

source software should be promoted and that the standard essential patents

regime was not particularly fit for the IoT space.

Their policy suggestion was to promote awareness about open source software and

the role it can play in an IoT driven business. “Patenting

software is dead and that is good . . . I would suggest that they spend more

time explaining Open Source Software to common people and to business . . . they

should find the European version of Open Source Software licensing, make it

more common, teach about it and sponsor work to formulate Open Source Software

licenses.” (B.)

In that respect it was proposed

that the E.C. could identify stimulation funds, however these should be made

available with as little administrative burden as possible. “Promote Open

Source Software . . . maybe also subsidies for stimulation funds, but in the end it is mainly the established firms that get that and the

true innovation comes from the small ones and they don’t access these funds

because it is too bureaucratic to get these funds.” (A.) Equally, more training on Open Source could be an alternative to

the traditional standard essential patent regime. “Anything the Government can

do to assure firms win by conquering markets and not by paying expensive

lawyers . . . I would suggest spending more resources in explaining Open Source

Software and focus much more on training firms in Open Source Software.” (B.)

Conclusions

The E.C. is eager to approach the role of SEPs in the IoT through the lens of the FRAND agreement. Through this

process the E.C.’s goals is provide further clarity of

what the FRAND commitment entails. While very important, this aspect is not

entirely reflective of the issues raised by the interviewees of this survey.

Hence, an additional section was added to the FRAND Guidelines that address the

need to raise awareness among SMEs (small and medium sized enterprises) on

standard essential patents and the role of the FRAND commitment. This is

entirely commensurate with the findings of this study.

Like the findings of Pikethly, Talvela and Nikzad,[43] the

survey showed that young innovative firms lack IP awareness and do not

understand the role that IP management could play for their firm. A good

illustration of this issue is that respondents showed two apparent

contradictory views on the IP system. On the one hand side

they lacked awareness on IP, on the other hand, they felt that the patent system

should be urgently reformed. This suggests that the senior managers in YICs

have, at best, a layperson’s understanding of the IP system and it underlines

the need for further IP awareness-building campaigns.

The interviewees also

had a minimal understanding of standard essential patents and the accompanying

FRAND debate, especially the early stage firms. This leaves them exposed to

unexpected licensing requests, while depriving them of the opportunity to

pursue their own licensing programs. Certainly, standard essential patent

owners focus their licensing programs on companies with significant revenues,

which is usually not the case of YICs. However, once YICs obtain critical mass,

they could be hampered in their growth due to licensing requests they did not

expect. If they do reach such a level, these licensing issues will require further

policy attention and there will be a need to raise awareness among YICs about

FRAND.

Against this backdrop, the FRAND guidelines will very likely

be accompanied by tailored awareness-raising measures that allow YICs to

adequately familiarize themselves with the peculiar challenges associated with

standard essential patents. The nature of the FRAND agreement deserves further

policy attention, but so does its practical applicability. This aspect was

given adequate consideration in the FRAND guidelines.[44]

If young innovative companies have not even heard of FRAND or standards

essential patents before, it is highly unlikely that they will be prepared to

formulate smart strategies as licensees or licensors. Nowhere are these concerns

included in the current policy debate. The European Commission and even

National Patent Offices are actively working towards raising IP awareness and

enhancing the understanding of IP among young innovative companies. However, so

far this has not been approached from a FRAND perspective. Adaptations are

sorely needed in light of the risk of patent wars[45] spreading to the IoT.

Lastly, there is a dire need to assume governance responsibilities

and identify a mediating structure between the inherent tensions prevailing

between the exclusionary features of patent law and the open, collaborative

nature of the Internet of Things. The interviews showed that the patent system

cannot be viewed in isolation and the benefits of other innovation strategies,

such as the promotion of open source software, need to be weighed against the

further advancement of the patent system. Many of the firms we talked to found

an open source strategy more effective than a patent strategy. They also

thought that the open architecture enabled by open source was more befitting of

the nature of the IoT.

Certainly, such statements need to be read with care, but at

present too much policy formulation is occurring in isolation. What the IoT needs is a cross-functional, horizontal policy

formulation, rather than policies developed in vertical silos. This can only be

achieved by bringing all actors in the IoT space into

the debate. Therefore, I urge policy makers to study further how IP can be

promoted as a tool to promote openness rather than as a means of segregation.

Annex: Table 1 – Overview of Interviewees

[1]

See, e.g., Ian Hargreaves, Digital Opportunity: A Review of Intellectual

Property and Growth, at 14-15 (2011) (U.K.), https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/digital-opportunity-review-of-intellectual-property-and-growth.

[2]

See The Internet

of Things, Eur. Comm’n (last visited Sept. 4,

2017) https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/policies/internet-things.

[3]

See Communication from the Commission

— Guidelines on the applicability of Article 101 of the Treaty on the

Functioning of the European Union to horizontal co-operation agreements, 2011

O. J. (C 11) 55; Chryssoula Pentheroudakis &

Justus A. Baron, Licensing Terms of

Standard Essential Patents: A Comprehensive Analysis of Cases, JRC Science for Policy Rep.

(Nikolaus Thumm ed., 2017);

Tim Pohlmann & Knut Blind, Landscaping study on Standard Essential Patents, IPlytics (2016), http://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/newsroom/cf/itemdetail.cfm?item_id=8981;

Pierre Reégibeau, Raphaêl De Coninck & Hans

Zenger, Transparency, Predictability, and

Efficiency of SSO-based Standardization and SEP Licensing: A Report for the

European Commission (2016) http://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/newsroom/cf/itemdetail.cfm?item_id=9028&lang=en;

Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry,

Entrepreneurship and SMEs, Public

Consultation on Patents and Standards – A Modern Framework forStandardisation Involving Intellectual Property Rights

(2015), http://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/newsroom/cf/itemdetail.cfm?item_id=7833;

European Competitiveness and Sustainable Industrial

Policy Consortium, Patents and Standards:

A Modern Framework for IPR-Based Standardization (2014), http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/4843/attachments/1/translations.

[4] Setting

Out the EU Approach to Standard Essential Patents, European Comm’n, https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/26583.

[5]

Directorate-General for Internal Mkt., Indus., Entrepreneurship and SMEs, Communication from the Commission on

Standard Essential Patents for a European Digitalised

Economy, Ares(2017)1906931 (2017), https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/initiatives/ares-2017-1906931_en.

[6]

See, e.g., Lea Shaver, Illuminating Innovation: From Patent Racing to Patent War, 69 Wash.

&n Lee Rev. 1891, 1933 (2012); Thomas H. Chia, Fighting the

Smartphone Patent War with RAND-Encumbered Patents, 27 Berkeley Tech. L. J. 209, 210, 239-238 (2012); Jeff Hecht, Winning the laser-patent war, 12

Laser Focus World 49, 49 (1994); Sonia Karakashian,

A

Software Patent War: The Effects of Patent Trolls on Startup Companies,

Innovation, and Entrepreneurship, 11

Hastings Bus. L.J. 119, 122 (2015);

Tim Bradshaw, Smartphone patent

wars set to continue, Financial Times, May 28, 2013, available at https://www.ft.com/content/3eda6296-b711-11e2-a249-00144feabdc0.

[7]

Aditi Das, Ashish Gupta, & Bhargav Ram, Speech Recognition Technology & Patent

Landscape, iRunway, (2015), at 26, available at http://www.i-runway.com/images/pdf/iRunway-Speech-Recognition-Patent-Landscape.pdf.

[9] LexInnova, The Internet of Things: Patent Landscape

Analysis, (Nov. 2014), available at http://www.lex-innova.com/resources-reports/?id=33.

[10]

William H. Dutton, The Internet of Things,

(June 20, 2013), https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2324902

(quoting William H. Dutton et al., A

Roadmap for Interdisciplinary Research on the Internet of Things: Social

Sciences’, addendum to Internet of Things Special Interest Group, A Roadmap for

Interdisciplinary Research on the Internet of Things. London: Technology

Strategy Board (January 5, 2013), https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2234664.

[11]

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development [OECD], Machine-to-Machine

Communications: Connecting Billions of Devices at 7, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 192 (Jan. 30, 2012), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k9gsh2gp043-en.

[12]

The Internet of Things, Eur. Comm’n, https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/policies/internet-things.

[13] See Raph Crouan,

Why are SMEs the single most important

element in our Alliance for IoT today?, Eur. Comm’n

(Nov. 20, 2015), https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/blog/why-are-smes-single-most-important-element-our-alliance-iot-innovation-today;

‘Internet of Things’ has huge potential

for SMEs, Knowledge Transfer Ireland,

http://www.knowledgetransferireland.com/News/‘Internet-of-Things’-has-huge-potential-for-SMEs.html;

The Business Drivers and Challenges of

IOT for SMEs, IOTUK, https://iotuk.org.uk/the-business-drivers-and-challenges-of-iot-for-smes/;

The business drivers and challenges of IoT for SMEs. https://iotuk.org.uk/the-business-drivers-and-challenges-of-iot-for-smes/.

[14]

S.J. Liebowitz & Stephen E. Margolis, Network Externalities (Effects), https://www.utdallas.edu/~liebowit/palgrave/network.html.

[15] See

Michael L. Katz & Carl Shapiro, Systems

Competition and Network Effects, 8.2 J. Persp. 93 (1994).

[16]

See Joseph Farrell & Paul

Klemperer, Coordination and Lock In:

Competition with Switching Costs and Network Effects, in 3 Handbook of Indus. Org. 1967 (Mark Armstrong

& Robert H. Porter eds., 2007).

[17]

Pierson Paul, Increasing Returns, Path

Dependence, and the Study of Politics, 94(2) Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 251, 251-67 (2000); see also Kenneth J. Arrow, Increasing

Returns: Historiographic Issues and Path Dependence, 7(2) Eur. J. of the Econ. Thought 171, 171-80

(2000).

[18]

See Vernon W. Ruttan,

Induced Innovation, Evolutionary Theory

and Path Dependence: Source of Technical Change, 107(444) The Econ. J. 1520, 1520-29 (1997);

Robert W. Rycroft & Don E. Kash, Path Dependence in the Innovation of Complex

Technologies, 14(1) Tech. Analysis

& Strategic Mgmt. 21, 21-35 (2002); Arthur

W. Brian, Increasing Returns and Path Dependence in the Economy, 46 (1994).

[19] See Venkatesh Shankar & Barry L. Bayus, Network

Effects and Competition: An Empirical Analysis of the Home Video Game Industry,

24(4) Strategic Mgmt. J. 375, 375-84

(2003).

[20] William B. Arthur, Increasing Returns and the Two Worlds of

Business, 74(4) Harv. Bus. Rev. 100, 100-09 (1996) (emphasis

added).

[21] Joseph S. Miller, Standard Setting, Patents, and Access

Lock-In: Rand Licensing and the Theory of the Firm, 40 Ind. L. Rev. 351, 378 (2007).

[22] See Dan Hunter, Cyberspace as

Place and the Tragedy of the Digital Anticommons,

91 Calif. L. Rev. 439, 439-519

(2003); Sven Vanneste et al., From “Tragedy” to “Disaster”: Welfare Effects of Commons and Anticommons Dilemmas, 26 Int’l Rev. of L. and Econ. 104, 104-22 (2006); Clarisa Long, Patents

and Cumulative Innovation, 2 Pol’y 229, 229-46 (2000).

[23]

See, e.g., U.S. Dep’t of Justice & Fed. Trade Comm’n,

Antitrust Enforcement and Intellectual Property Rights: Promoting Innovation

and Competition (2007) (addressing ‘hold up’ in the context of standard

setting).

[24]

Philippe Chappatte, FRAND Commitments – The Case for Antitrust

Intervention, 5 Eur. Competition J.

319, 326 (2009).

[25] Joseph

Farrell, John Hayes, Carl Shapiro & Theresa Sullivan, Standard Setting Patents and Hold-Up, 74 Antitrust L. J. 603, 608 (2007).

[26]

See, e.g., U.S. Dep’t of Justice & U.S. Fed. Trade Comm’n,

supra note21

(addressing hold up in the context of standard setting); Mark A. Lemley & Carl Shapiro, Patent Hold-up and Royalty Stacking, 85

Texas L. Rev. 1991 (2007); Carl Shapiro, Injunctions, Hold-Up, and Patent Royalties, 12 Am. L. & Econ. Rev. 280 (2010). For a critique of Lemley & Shapiro, see

Einer Elhauge, Do Patent Holdup and Royalty Stacking Lead

to Systematically Excessive Royalties?, 4 J. Competition L. & Econ 535 (2008); John M. Golden, “Patent

Trolls” and Patent Remedies, 85 Texas L. Rev 2111 (2007); Vicenzo

Denicolò, Damien Geradin,

Anne Layne-Farrar, & A. Jorge Padilla, Revisiting

Injunctive Relief: Interpreting Bay In High-Tech Industries With Non-Practicing

Patent Holders, 4 J. Competition L. & Econ 571 (2008); Peter Camesasca, Gregor Langus, Damien Neven, & Pat Treacy,

Injunctions for Standard-Essential

Patents: Justice Is Not Blind, 9 J. Competition L. & Econ 285

(2013); James Ratliff & Daniel L. Rubinfeld, The Use and Threat of Injunctions in the

RAND Context, 9 J. Competition L. & Econ 1 (2013).

[27]

Gregor Langus, Vilen Lipatov & Damien Neven,

Standard-Essential Patents: Who Is Really

Holding Up (and When)?, 9 J. Competition L. & Econ.,

253 (2013); Damien Geradin, Reverse Hold-Ups:

The (Often Ignored) Risks Faced by Innovators in Standardized Area The Pros and Cons of Standard Setting,

(Nov. 12, 2010) (paper prepared for the Swedish Competition Authority on the

Pros and Cons of Standard-Setting).

[28]

Michael J. Meurer, Controlling Opportunistic and

Anti-Competitive Intellectual Property Litigation, 44 B.C. L. Rev. 509 (2003).

[29] Dirk Czarnitzki & Julie Delanote, Young

Innovative Companies: The New High-Growth Firms?, 1 (Ctr. for Eur. Econ. Research,

Discussion Paper No. 12-030) (2012).

[30] Robert

H. Pitkethly, Intellectual

Property Awareness, 59 Int’l

J. Tech. Mgmt. 163 (2012).

[31]

Robert Pitkethly, UK

Intellectual Property Awareness Survey 2006, Chronicles of Intellectual Prop.,

http://breese.blogs.com/pi/files/ipsurvey.pdf; Preliminary Report, Intellectual Property Awareness Survey 2015 (Feb.

11, 2016), https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/500211/IP_awareness_survey_2015.pdf.

[32]

See IPeuropeAware,

Promoting the Benefits of greater knowledge and effective management of

European SMEs & Intermediaries, https://www.dpma.de/docs/dpma/conclusion_paper_ipeuropaware.pdf;

European IPR Helpdesk, https://www.iprhelpdesk.eu/ambassadors

(last visited Dec. 1, 2017).

[33]

See World

Intellectual Property Organization, http://www.wipo.int/ip-outreach/en/tools/

(last visited Dec. 1, 2017).

[34]

Intellectual Property Office, From Ideas to Growth: Helping SMEs get value from

their intellectual property (Apr. 3, 2012), https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/316116/ip4b-sme.pdf;

Competitiveness and Innovation Framework Programme, IP

Awareness and Enforcement Modular Based Actions for SMEs, http://www.obi.gr/obi/portals/0/imagesandfiles/files/abstract_en.pdf.

[35]

Ian Hargreaves, Digital Opportunity: A Review of Intellectual Property and

Growth (May 18, 2011), https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/32563/ipreview-finalreport.pdf.

[36]

Patents for software? European law and

practice, Eur. Pat. Off.,

https://www.epo.org/news-issues/issues/software.html (“Under the EPC, a

computer program claimed “as such” is not a patentable

invention (Article 52(2)(c) and (3) EPC). Patents are not granted merely for

program listings. Program listings as such are protected by copyright. For a

patent to be granted for a computer-implemented invention, a technical problem

has to be solved in a novel and non-obvious manner.”).

[37]

See generally Margaret C. Harrell

& Melissa A. Bradley, Data Collection

Methods: Semi Structured Interviews and Focus Groups, RAND Nat’l Def. Res. Inst., at 27

(2009); Siw. E. Hove & Bente

Anda, Experiences

from conducting semi-structured interviews in empirical software engineering, Software Metrics, 2005, at 3.

[38]

See, e.g., Mark Manson, Sample

Size and Saturation in PhD Studies Using Qualitative Interviews, Forum:

Qualitative Soc. Res., Sept. 2010, at 3, 9 (citing several major works

recommending between 20-50 interviews and finding an average of 31 among studies

included in analysis).

[39]See Florian Kohlbacher, The Use of Qualitative Content Analysis in

Case Study Research, Forum: Qualitative Soc. Res., Jan. 2006, at 13.

[40]

On an anonymized basis and subject to prior approval the transcripts of the

interviews are available upon request.

[41]

IP Europe Alliance, About Us, IP Europe,, https://www.iptalks.eu/

(last visited Nov. 9, 2017).

[42] Fair Standards Alliance, Our Vision, Fair Standards Alliancehttp://www.fair-standards.org/ (last visited Nov. 9, 2017).

[43]

Robert Pitkethly, Intellectual Property Awareness, 59 Int’l J. of Tech. Mgmt. 163 (2010); Juhani

Talvela, How to Improve the Awareness and Capabilities of Finnish

Technology Oriented SMEs in Patent Related Matters, ResearchGate, June 2016, available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Juhani_Talvela/publication/316735577_How_to_Improve_the_Awareness_and_Capabilities_of_Finnish_Technology_Oriented_SMEs_in_Patent_Related_Matters/links/590f8bbea6fdccad7b126a31/How-to-Improve-the-Awareness-and-C;

Rashid Nikzad, Small

and medium-sized enterprises, intellectual property, and public policy, 42 Sci. & Pub. Pol’y

176, 178-179, 183 (2014); Robert Pitkethly, UK Intellectual

Property Awareness Survey 2010,

Intell. Prop. Office (2010), available at http://www.ipo.gov.uk/ipsurvey2010.pdf.