Victoria Thede *

Download a PDF version of this article here.

Art historian Hal Foster and his colleagues write of the accelerating convergence between fine art and consumer goods: “artistic and commercial, high and low, rare and mass, expensive and cheap, and so on. There is little tension, and not much insight, now that these pairs have imploded—just a giddy delight, a weary despair, or a manic-depressive cocktail of the two.”1 Nowhere is this messy collision more evident than the arena of non-fungible tokens (NFTs), where artists and fashion designers compete in their aspirations to lay claim to the medium for their works.

This article uses the recent litigation between luxury fashion house Hermès and artist Mason Rothschild over a series of so-called “MetaBirkin” NFTs to examine whether the test developed in Rogers v. Grimaldi can effectively resolve disputes over trademark infringement by expressive works. The non-dimensionality of the NFT challenges the premise that paintings and purses are all that different and exposes the broader “crisis of the object” that inspires art and plagues trademark law. As contemporary art has increasingly used the medium of the artwork to challenge its capitalist context, the Rogers inquiry has grown ineffectual at delineating the boundaries between infringing and non-infringing expressive works at the intersection of art and fashion.

Introduction

In the case of luxury French fashion house Hermès, its renown for high-quality handbags may lack worthy competition; style critics compare the brand’s “handwork” manufacturing process to the “tradition of Europe’s medieval craft guilds” and laud the results as “perfect.”2 The iconic Birkin bag (Fig. 1)3 is the fruit of a famous encounter on an Air France flight between actress Jane Birkin and the executive chairman of Hermès at the time, Jean-Louis Dumas, in 1984.4 Now each handbag typically sells for between four- and six-figures, whether consigned or brand-new, depending on the rarity of the model.5 In December of 2021, artist Mason Rothschild sold the rights to individual non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”) as part of a series entitled the “MetaBirkins,” with each NFT representing an image of a Birkin bag covered in fur (Fig. 2)6.7 Rothschild explained that he wanted to, in his words, “create that same kind of illusion that [the Hermès Birkin bag] has in real life as a digital commodity.”8 Rothschild and his team earned $1.1 million from the one hundred MetaBirkins sold between December of 2021 and June of 2022.9

Trademark law helps consumers to distinguish among goods on the basis of their source and thereby incentivizes producers to build up a brand-name reputation for their products.10 The threshold question for any trademark suit, then, is whether the copied mark has earned a sufficiently distinct reputation such that it deserves the protection of the law in the first place.11 Given the global renown of Birkin handbags, it comes as no surprise that courts have opted to protect the trade dress of the distinctive Hermès bag against counterfeiters in the past.12 To succeed in an action for trade dress infringement under Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act, the plaintiff must first prove “that the mark is distinctive as to the source of the good” by demonstrating that the mark either is inherently distinctive or has acquired distinctiveness, also known as secondary meaning.13 In the case of product design, such as the distinctive silhouette of a Birkin bag, the Supreme Court has held that it can only achieve protection under Section 43(a) with a showing of secondary meaning.14 For example, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York found in 2004 that the unique shape of Cartier’s Tank and Panthère watches possessed secondary meaning, meaning that “in the minds of the public, the primary significance of a [mark] is to identify the source of the product rather than the product itself,” on the basis of a consideration of factors including “advertising expenditures, consumer studies, sales, competitors’ attempts to plagiarize the mark, and the length and exclusivity of the mark’s use.”15 While courts have generally opted to reflexively presume that Hermès Birkin bags represent a protectable mark without elaboration,16 this close analogue in the luxury space demonstrates the rationale behind finding that the trade dress of the Birkin bag has acquired secondary meaning.

The weighty concerns in favor of strong trademark enforcement must account for the constitutional protection of freedom of expression. Trademark law once adopted a “no alternative avenues” of communication test, such that “where adequate alternative avenues of communication” exist, the infringing expressive message is not protected by the First Amendment.17 In the landmark 1989 case Rogers v. Grimaldi, however, the Second Circuit overturned this standard and developed a novel test for balancing trademark rights with freedom of expression:18

We believe that in general the [Lanham] Act should be construed to apply to artistic works only where the public interest in avoiding consumer confusion outweighs the public interest in free expression. In the context of allegedly misleading titles using a celebrity’s name, that balance will normally not support application of the Act unless the title has no artistic relevance to the underlying work whatsoever, or, if it has some artistic relevance, unless the title explicitly misleads as to the source or the content of the work.19

In the Second Circuit, the Rogers test applies where the “unauthorized use of another’s mark is part of a communicative message and not a source identifier,”20 particularly to “commentary, … news reporting or criticism.”21 The Rogers test distills the policy tension between trademark law and freedom of expression to a dual-pronged test. Rogers shields trademark use in expressive works under the Lanham Act where the “defendant’s use of the mark or other identifying material is (1) ‘artistically relevant’ to the work and (2) not ‘explicitly misleading’ as to the source of content of the work.”22 Whether the Rogers test protects Rothschild’s MetaBirkins at all depends on whether his work is “part of a communicative message and not a source identifier”—in other words, whether it is art or just a knock-off Birkin.

Hermès brought the trademark action at hand against Rothschild in January of 2022 and presented four sets of allegations in its Amended Complaint, claiming in part that “the MetaBirkins NFTs infringe Hermès’ trademarks in the word ‘Birkin’ and in the design and iconography of the handbag” and that “Rothschild’s alleged appropriation of the ‘Birkin’ mark diluted and damaged the distinctive quality and goodwill associated with the mark.”23 Hermès asserted that the MetaBirkins did not qualify as artistically expressive and therefore did not deserve protection under the First Amendment, because Rothschild released the MetaBirkins NFTs with the intention of “[p]rofit, [n]ot [e]xpression” by minting a “digital brand.”24 Rothschild described himself as “a marketing king” who was “sitting on a gold mine” and proposed minting a similar set of watch NFTs entitled “MetaPateks” after the luxury watch brand Patek Philippe.25 Hermès capitalized on Rothschild’s own statements to media outlets in the wake of his release of the MetaBirkins to suggest that his work represented a meaningless, yet lucrative, “digital commodity” as opposed to a work of artistic expression.

The seminal Rogers test fails to provide an adequate path that allocates ownership to either designer brands or contemporary artists over the arena of NFTs, and this particular “crisis of the object” forebodes broader difficulties in distinguishing between infringing and non-infringing expression. In addition to collaborating more co-extensively in recent years, luxury fashion and contemporary art also compete to conquer the NFT space. The MetaBirkins series of NFTs at issue in Hermès International v. Rothschild exemplifies the difficulties posed at this borderland between First Amendment and trademark law.

I. What are NFTs?

NFTs are non-interchangeable digital assets that creators can sell on a blockchain via “smart contracts” which self-execute.26 NFTs “point to things,” and “[w]hile NFTs can point to anything, one of the first applications of NFT technology was in the realm of digital art.”27 The modern art establishment that has long traded in Picassos has welcomed NFT artworks with open arms. The Guggenheim Museum has accepted a significant contribution from an electronics company and accordingly dedicated those resources toward digital artwork and “the Metaverse.”28 Turkish artist Refik Anadol used an artificial intelligence model to transform the hundreds of thousands of pieces of content from the archive of the Museum of Modern Art (“MOMA”) into dizzying video displays where masterpieces morph into each other in rapid sequence, and the MOMA earned a fraction of the sales revenue for each NFT the artist sold.29 Cryptocurrency experts assert that NFTs “are more akin to objects of art or collectibles than currencies.”30

Yet the myriad potential classifications of NFTs implicate the case at hand. NFTs could fall under existing regulation for commodities due to the close resemblance of certain digital currency transactions to derivative financial instruments, including “futures, options, [and] swaps” that “derive their value from something else, including, for example, a benchmark rate, a physical commodity such as oil or wheat, or digital asset commodities.”31 In 2023, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission successfully filed in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois for a consent order and permanent injunction of the cryptocurrency platform Binance according to the theory that the platform “offer[ed] digital asset derivative products” classified as commodities under federal law, although the order did not clarify the status of NFTs in particular as opposed to the other cryptocurrency transactions at issue in the consent order.32

Alternatively, NFTs could be classified as investment contracts. The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York held in Friel v. Dapper Labs, Inc. that NFTs called “Moments”—depicting notable moments of NBA players—could constitute securities in February of 2023.33 The court made this determination that the Moments could represent an investment contract by establishing that the NFTs met the three prongs of the so-called Howey test, established by the Supreme Court in SEC v. W.J. Howey Co. “(1) an investment of money (2) in a common enterprise (3) with the expectation of profit from the essential entrepreneurial or managerial efforts of others.”34 That said, the court noted that whether the Moments were securities “toes [the] line intimately” and characterized its ruling as “narrow,” clarifying that “[n]ot all NFTs offered or sold by any company will constitute a security, and each scheme must be assessed on a case-by-case basis.”35 The Securities and Exchange Commission likewise successfully charged Stoner Cats 2 LLC with unregistered offering and sale of “crypto asset securities” for its sale of so-called “Stoner Cats” NFTs, for which the company consented to a cease-and-desist order and payment of a civil penalty.36

By virtue of their disputed legal status and their shared qualities with various financial instruments, the MetaBirkins carry the reputation of NFTs and cryptocurrencies at large as “a risky and speculative market that has been plagued by grifters.”37 The Supreme Court determined in Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association that video games constituted expressive works because they “communicate[d] ideas” and “social messages … through features distinctive to the medium (such as the player’s interaction with the virtual world).”38 If the MetaBirkins are works of art, they communicate “through features distinctive to the medium” of the NFT. Any artistic message that the MetaBirkins may express is necessarily filtered through the viewer’s perception of the NFT as a speculative financial instrument. The NFT sits uncomfortably at the intersection of commodity, security, and provocative artistic medium.

II. Threshold Inquiry to the Rogers Test

A. From “Is This Art?” to “Is This a Mark?”

At the time of the Hermès trial, the threshold question under the Rogers test was whether the work qualified as expressive. Presided over by Judge Jed Rakoff, the court noted in its order denying the parties’ cross-motions for summary judgment that neither Rogers nor its progeny in the Second Circuit had thoroughly delineated a clear understanding of what exactly comprises “artistic expression” within the Rogers framework.39 A clearer standard emerged from the Ninth Circuit that is particularly relevant to digital media. Citing Brown, the Ninth Circuit held that even though the video game in question was not necessarily “the expressive equal of Anna Karenina or Citizen Kane,” it nonetheless fell under the Rogers test because it was “expressive.”40 Likewise, in Gordon v. Drape, the Ninth Circuit determined that a set of greeting cards qualified for application of the Rogers test because “greeting cards are expressive works protected under the First Amendment” and cited the expressive element as “[a]n intent to convey a particularized message, … and in the surrounding circumstances the likelihood was great that the message would be understood by those who viewed it.”41 The Ninth Circuit articulated a standard whereby works that the First Amendment protects as expressive pass the initial threshold of the Rogers test, and the courts define “expressive” broadly using language akin to the Supreme Court in Brown v. Entertainment Merchants to encompass works that express “ideas” and “messages” using “features distinctive to the medium.”

In 2023, the Supreme Court pushed for a shift in emphasis away from the expressive qualities of the work and toward the function of source identification because the latter is the “primary mission” of trademark law.42 The dispute centered between Tennessee whiskey brand Jack Daniel’s and a dog-toy company which released a line of so-called “Bad Spaniels” and “Silly Squeakers” dog toys in the distinctive shape of the Jack Daniel’s whiskey bottle.43 Justice Elena Kagan delivered the Opinion of the Court and held the Rogers test does not apply where an infringer is “trading on the good will of the trademark owner to market its own goods”—that is, the infringer is using the infringed-upon mark for the purpose of “source identification.”44 Stated differently, Rogers “does not apply if the defendant uses the similar mark as a mark,”45 as opposed to the Ninth Circuit standard “that Rogers applied to all ‘expressive work[s].’”46 As any critical visitor to a contemporary art museum knows, artists of the early twentieth-century relentlessly challenged the older, narrower conception of what is “art,” and consequently, our own popular conception of expressive works has grown more expansive with ill-defined boundaries.47 It is no surprise, then, that under the former threshold inquiry into the expressive qualities of the work, courts overwhelmingly tended to find expressive qualities in otherwise infringing works and granted Rogers protection.48

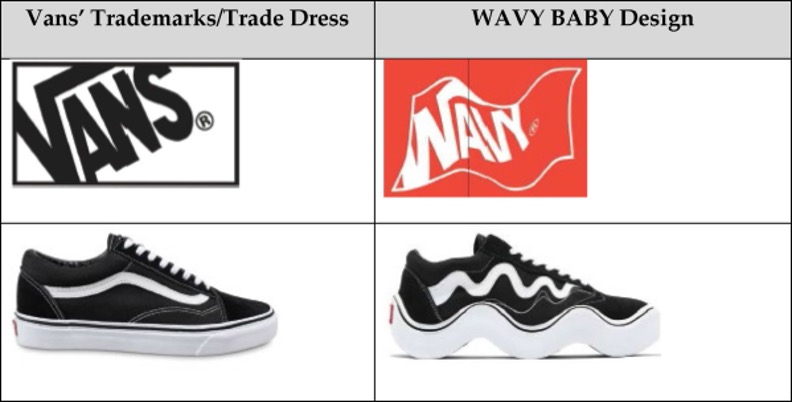

Jack Daniel’s effectively replaced this pre-existing, “defendant-friendly” inquiry into expressive value with an alternative inquiry into the source-identifying function of the infringement, tipping the balance toward finding the work infringing and against finding the work eligible for Rogers deference.49 Accordingly, when the sneaker company Vans filed suit against an art collective known as MSCHF, which sold a line of sneakers that distorted the trade dress and trademarks of the iconic Vans sneaker to produce a “Wavy Baby” line of sneakers (Fig. 3)50, the Second Circuit found that MSCHF was using the trademarks and trade dress of the Vans sneaker as a “source identifier” for its own sneakers in a similar fashion to the “Bad Spaniels” use of the Jack Daniel’s marks.51 The court asserted that the “black and white color scheme, the side stripe, the perforated sole, the logo on the heel, the logo on the footbed, and the packaging” of the MSCHF sneaker evoked the Vans Old Skool sneaker in a way that would “brand its own products.”52 Where the courts once asked, “Is this art?,” they now ask, “Is this a mark?” Both inquiries are broad and easy to answer in the affirmative.

B. Art as Branding

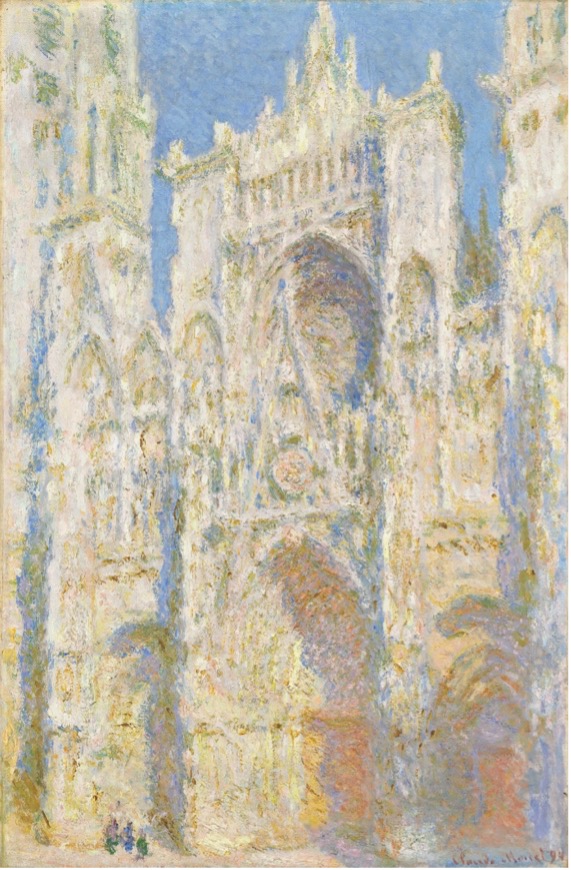

Contrary to both the old and new threshold inquiries for Rogers deference, the boundary between artwork and branding proves fuzzy under scrutiny. Beginning in 1891, art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel exhibited multiple series of paintings by Claude Monet such as Haystacks, Poplars, Rouen Cathedral (Figs. 4-5)5354, Views of the Thames, and the artist’s famous Water Lilies.55 These series were, in the words of art auctioneer Philip Hook, “a dealer’s dream, visually stupendous treatments of the same subjects under the varying light conditions of different times of day. Ten or twenty at a time, they flowed into his gallery for exhibition and sale with the paint barely dry on them.”56 Durand-Ruel needed to go to great lengths to sway the press and customers that Monet’s series had an artist’s touch and did not reduce his artistic brilliance to a mere “painting factory,” all while the dealer himself participated proactively in “[t]he active branding of artists as commodities” and the “manipulat[ion of] the performance of their works at auction.”57 Monet also once wrote to Durand-Ruel to ask that he work with a rival dealer named Georges Petit whose artists seemed to be immune from public criticism because, in Monet’s words, their “paintings are mounted advantageously” and “because of the luxury of the room.”58 Hook writes that Petit’s strategy represented “the first stage in the reinvention of the Impressionist painting as luxury object.”59

Monet’s series share a common structure with MetaBirkins—a set of depictions of the same subject with slight color alterations, packaged all together yet sold individually. Moreover, as Hook illustrates through his comparison of art dealer Petit’s strategy to the sale of luxury objects, the commodity-like quality that characterizes the MetaBirkins is just as much of a feature of luxury handbags and modern art. The serial nature of Rothschild’s work particularly evokes the factory-like process for the manufacture of both Monet cathedrals and Birkin bags. The MetaBirkins harness the serial, commodified, and speculative qualities of NFTs to skewer both luxury handbags and fine art and emphasize their own status as, in Rothschild’s words, “digital commodities.”

C. Rogers’ Artificial Distinction between “Art” and “Mark”

The court in Hermès ultimately determined that Rogers nonetheless governed the case at hand because “using NFTs … does not make the image a commodity without First Amendment protection any more than selling numbered copies of physical paintings would make the paintings commodities for purposes of Rogers.”60 To establish that the MetaBirkins series represented an expressive work rather than a commodity, the court needed to draw an artificial distinction between commodities and artworks. Historic works of modern art such as Monet’s cathedrals already elided such a dichotomy, and the novel generation of NFT artworks similarly cannot be neatly divided into these two categories. As Dapper Labs, the C.F.T.C. stance against Binance, and the art world’s cozy reception to NFTs altogether demonstrate, NFTs do not fall cleanly into traditional categories of artistic expression deserving of Rogers deference.

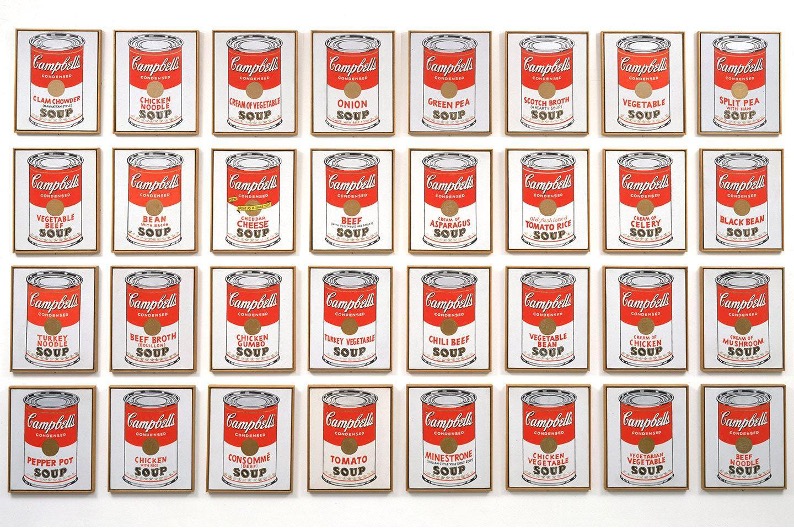

Yet Kagan’s inquiry is equally ill-adapted to the contemporary art environment. As discussed above, artists have been crafting “marks” for themselves in the form of visual motifs since at least the Impressionist movement. According to Foster, “This serial ordering … oriented Pop [art] to the everyday world of serial commodities more systematically than any previous art” and forged a direct connection between consumer culture and the brand of the artist.61 Artist Andy Warhol’s well-known, mass-produced silkscreens of Campbell’s soup cans (Fig. 6)62 particularly evoke the serial quality of Monet’s cathedrals while calling attention to consumer objects, albeit household items of a more pedestrian quality than Birkin bags.63 These soup cans have come to “brand” Warhol’s artistic image to the extent that many art museum visitors can immediately identify Warhol as the source of a silkscreen-printed image of a Campbell’s soup can. Under Kagan’s inquiry, Warhol’s soup cans could evidently serve the purpose of source identification, whether that was Warhol’s intention or not. Using the indicia of consumer brands to critique consumerism has become an archetypal strategy for contemporary art, from Warhol’s use of Campbell’s soup cans through Rothschild’s MetaBirkins. As artists imitate capitalist branding in their artwork, they increasingly blur the separation between artwork and branding that the new Rogers threshold test relies upon.

The old inquiry asked, “Is this art,” while the new inquiry asks, “Is this a mark?” While both investigations are sensible and important ones to make in this context, they also both prove inherently tautological. The questions they ask are philosophical, and neither inquiry provides any guardrails for how to resolve them. Kagan appears somewhat knowledgeable of the nebulous quality of this investigation into art-versus-mark when she suggests that the standard “likelihood-of-confusion inquiry does enough work to account for the interest in free expression.”64 As I will discuss below, such an assurance is misplaced in the context of contemporary art.

III. First Prong of Rogers Artistic Relevance

After passing the initial threshold inquiry, the first prong under Rogers is whether the “defendant’s use of the mark [is] … ‘artistically relevant’ to the work.”65 As the court in Hermès expounds with citation to Rogers, “[t]he threshold for ‘artistic relevance’ is intended to be low and will be satisfied unless the use ‘has no artistic relevance to the underlying work whatsoever.’”66 According to the Ninth Circuit, “the level of relevance merely must be above zero.”67 An illustrative example lies in Louis Vuitton Mallatier S.A. v. Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc., whereby Louis Vuitton contended that Warner Bros. featured knock-off bags that infringed upon the Louis Vuitton mark in the film The Hangover: Part II.68 In a scene at the airport before a flight to Thailand, one character remarks to another of his bag, “Careful … that [bag] is a Lewis Vuitton.”69 The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York determined that the character’s comment “comes across as snobbish only because the public signifies Louis Vuitton … with luxury and a high society lifestyle” as well as “ironic because he cannot correctly pronounce the brand name of one of his expensive possessions, adding to the image of Alan as a socially inept and comically misinformed character.”70 Upon these grounds, the court concluded that the use of the Louis Vuitton mark in the film met the “artistically relevant” prong of Rogers.71 This inquiry of Rogers separates expression that incorporates a famous mark to provide social commentary from expression that intends to profit off of the goodwill of the mark, and in The Hangover: Part II, the Louis Vuitton reference serves to satirize Louis Vuitton in the form of social commentary.

In a similar fashion to the Hangover character who mispronounces Louis Vuitton, the Birkin bag is “artistically relevant” to the work insofar as it connotes luxury to skewer its meaninglessness. The medium of the NFT is essential to that process because, as the mediator between the content and the viewer, it filters our vision of the Birkin bag through the cultural reputation of NFTs. Rothschild provokes the popular view of NFTs as vacuous “digital commodities” and compares them to the similarly empty, speculative nature shared by both luxury handbags and modern art. In Hermès, the court determined that “there is a genuine factual dispute” as to whether the use of the Birkin mark bears any artistic relevance to the MetaBirkin project and left this determination to the jury.72 The court in Hermès framed this inquiry into artistic relevance as an investigation into “whether Rothschild’s decision to center his work around the Birkin bag stemmed from genuine artistic expression or, rather, from an unlawful intent to cash in on a highly exclusive and uniquely valuable brand name.”73

The dichotomy between “genuine artistic expression” and “an unlawful intent to cash in” does not map well onto the art world, which has long had an ambivalent relationship with “cashing in.” Seventeenth-century Netherlands represented the “greatest concentration of wealth on the planet until the emergence of Wall Street.”74 By virtue of their status as international sea-faring merchants, the Dutch had access to fantastic foreign objects that could serve as attractive status symbols.75 Since the Dutch were Calvinists, riches demonstrated a merchant’s status as a member of “the elect,” a clear sign of God’s favor.76 Yet Calvinists also espoused the eschewal of the delights of this world to hold out for the ecstasy of Heaven.77 To align their desire to display God’s favor with their antipathy toward sinful earthly pleasures, the Dutch developed a “compromise,” one that scholar Julie Berger Hochstrasser calls “window shopping.”78 Rather than display the physical possessions themselves, the Dutch instead depicted them in still-life paintings known as vanitas, which positioned the luxury objects alongside symbols of death and rebirth to indicate that earthly goods could not distract the Dutch from their heavenly aspirations.79

The MetaBirkins thematically closely align with the Dutch vanitas. In Willem Claesz Heda’s Vanitas (Still Life) (Fig. 7)80, painted between 1633 and 1635, a gold figurine and gold goblet dazzle in the foreground.81 The New World was home to the vast majority of global silver mining in the seventeenth century, so Heda’s depiction of a silver tazza particularly evokes exotic luxury.82 Heda pairs these symbols of mercantile success with an extinguished candle, a skull, and a celestial globe to allude to the transience of mortal time, the imminence of death, and the rapture of the heavens.83 The trio of luxuries paired with the trio of symbols of mortality suggest that the owner of this still-life has not forgotten the fleeting nature of earthly pleasures in his pursuit of riches. Both Heda’s painting and the MetaBirkins use their own respective medium to impose a distance between the consumer and the luxury object, transforming the item from something tangible into a two-dimensional depiction. Without being able to touch the skin of a Birkin bag or the cold metal of the tazza, these objects lose their tactile qualities and their utility as containers and instead become meaningless investment items. This flattening of the object forces the viewer to examine its luxury in a critical fashion.

The artist’s self-consciousness of his own mercenary aims later became the obsessive focus of contemporary art in the mid- to late twentieth century,84 and the artistic relevance of the MetaBirkins lies in their placement within this longstanding thematic tradition. Andy Warhol quipped in 1975: “Business art is the step that comes after Art.”85 Art critic Blake Gopnik asserted that Rothschild’s mercenary aims should not disqualify him from the protection of the First Amendment, noting that “Leonardo da Vinci and Andy Warhol both loved making a buck.”86 Gopnik also asserted that he “couldn’t see any real difference between Rothschild and the many artists, good and bad, who made art about our culture’s commerce, often by including trademarked goods,” including Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soups, Coca-Colas and Brillo Boxes.”87 In this era of business art, a critique of the Birkin bag as a vacuous status symbol continues the lineage of artistic targeting of capitalism from Dutch vanitas through Warhol.

The Rogers analysis for artistic relevance does not effectively account for NFTs that feature famous marks. If the NFT medium itself instills the work with an ironic commentary on consumer culture by virtue of the NFT’s status at the crosshairs of art, commodity, and investment contract, then an artist could support incorporating any famous mark into his NFT artwork with the justification that it represents a commentary on consumerism. In the face of this dilemma, the courts have instead crafted an alternative false dichotomy that juxtaposes “genuine artistic expression” and “an unlawful intent to cash in” when, in the context of contemporary art, “genuine artistic expression” is entirely concomitant with an “intent to cash in”;88 as Gopnik noted, all artists work for compensation, going back to the Renaissance. This impossible binary could ensnare any NFT artwork that incorporates a famous mark.89

The artistic obsession with the relationship between art and commodity—seeping into still-life from the wealthiest pockets of seventeenth-century Europe and emerging to the surface amidst the boom of speculative financial interests that characterized the 1980s—has come to characterize contemporary art at large and particularly defines Rothschild’s stated purpose for the MetaBirkins as “digital commodities.”90 This gradual merger of commodity and art over the course of the past few decades, which arguably were never actually separate to begin with, renders the judicial distinction between “genuine artistic expression” and “an unlawful intent to cash in” inapposite for the examination of artistic expression. This dichotomy between art and cash categorized the MetaBirkins just as poorly as it did the art that led up to them. Moreover, the general inquiry by Rogers into “artistic relevance” proves excessively reductive in the face of NFTs by virtue of their status at the intersection of commodities and fine art. NFTs confound attempts by jurists to define the artistic relevance of their images because the NFT itself is already so heavily laden with symbolism by virtue of its medium to the point where it may not even seem to many observers like a work of art at all, particularly in the wake of Dapper Labs. The MetaBirkins are the natural culmination of the artist’s self-interested conception of his artwork as a luxury good and trading commodity, beginning with Dutch vanitas paintings and continuing through Monet’s cathedrals and Warhol’s soup cans. The medium of the NFT, in its interstitial status between commodity, security, and work of art, brings this tension between art and the market to the surface.

IV. Second Prong of Rogers: Explicitly Misleading

The second prong of Rogers is whether the “defendant’s use of the mark or other identifying material is … ‘explicitly misleading’ as to the source of content of the work.”91 In the Southern District of New York, the extent to which a mark explicitly misleads is evaluated under the Polaroid factors, as enumerated in Polaroid Corp. v. Polarad Electronics Corp.92 As applied in Hermès, the factors were:

(1) the strength of Hermès’ mark, with a stronger mark being entitled to more protection; (2) the similarity between Hermès’ “Birkin” mark and the “MetaBirkins” mark; (3) whether the public exhibited actual confusion about Hermès’ affiliation with Rothschild’s MetaBirkins collection; (4) the likelihood that Hermès will “bridge the gap” by moving into the NFT space; (5) the competitive proximity of the products in the marketplace; (6) whether Rothschild exhibited bad faith in using Hermès’ mark; (7) the respective quality of the MetaBirkin and Birkin marks; and, finally, (8) the sophistication of the relevant consumers. 93

While the Polaroid factors are used in the typical test for assessing likelihood of confusion in cases of trademark infringement, as the Hermès court explains, “the most important difference between the Rogers consumer confusion inquiry and the classic consumer confusion test is that consumer confusion under Rogers must be clear and unambiguous to override the weighty First Amendment interests at stake.”94 In such “classic” consumer confusion cases, plaintiffs in the Second Circuit have a harder time surpassing this test as compared to plaintiffs in other circuits.95 Under Rogers, the plaintiff bears an even heavier burden to demonstrate that the defendant’s infringement justifies overriding the right to freedom of artistic expression.

A. Sleight-of-Hand: Similarity and Actual Consumer Confusion

The second Polaroid factor considers the similarity between the expressive work and the mark it infringes, while the third factor looks to the actual confusion experienced by potential consumers about whether Hermès was the source of the MetaBirkins project. The similarity between the “Birkin” and “MetaBirkins” marks is substantial, both in terms of the words and the associated goods—Birkin bags and images of furry MetaBirkin bags. As to the third factor of actual consumer confusion, as the court noted, Hermès presented mixed evidence of consumers experiencing actual confusion.96 Both factors serve as benchmarks for the propensity of the expressive work to confuse potential consumers, yet they also function as key mechanisms by which the artwork is able to express insightful social commentary about a famous brand at all.

The inquiry into confusion cuts to the sleight-of-hand by which the contemporary artist plays with the viewer’s association with the brand. Artist Marcel Duchamp was the principal founder of the Dada movement, which transformed “ready-made” objects into novel works of art, such as flipping a urinal on its back to create a so-called “Fountain.”97 Critic Lucy Lippard writes of the artist, “His fine French hand can be discerned in the evolution of everything from pop art to earthworks.”98 In 1936, writer André Breton in his seminal essay “Crisis of the Object” explained the significance of Duchamp’s innovation: “Objects thus reassembled have in common the fact that they derive from, and succeed in differing from the objects which surround us, by simple change of role.”99 Breton wrote his essay to accompany his exhibition by Surrealist artists that included Salvador Dalí and Joan Miró alongside a now little-known artist named Meret Oppenheim.100

One year prior, Oppenheim had bumped into Pablo Picasso and Dora Maar at a Paris café.101 As the two of them examined the fur-covered bracelet that Oppenheim wore as a prototype for jewelry that she was designing for fashion icon Schiaparelli, Picasso commented that “anything could be covered with fur,” to which Oppenheim replied, “Even this cup and saucer?”102 Oppenheim would transform this banter into a work of art for Breton’s exhibition (Fig. 8)103, buying “a large cup, saucer, and spoon at a cut-rate department store and cover[ing] its glazed white surfaces with the pelt of a Chinese gazelle.”104 The resulting “Object,” as it was named,105 appears strikingly similar to the MetaBirkins: it is a readymade object covered in fur. Both also invert the ready-made in a similar fashion, by rendering a once-useful object thoroughly inoperable. Breton describes Oppenheim’s work as a successful iteration of the Surrealist imperative to “hound the mad beast of function.”106 The furry tea-cup can no longer serve tea, because it both is covered in fur and now serves principally as an artwork in a museum, and the MetaBirkin is just as useless, corrupting the carry-all purpose of the Birkin bag by covering its leather skin with fur as well as flattening its form to a digital image.

Most importantly, both works find their shock value in the initial confusion exhibited by the viewer, and the similarity of the shapes of the silhouettes of the bags and the corresponding name of MetaBirkins are what facilitate this sleight-of-hand. Upon seeing the furry tea-cup, the viewer instantly imagines the taste of fur in one’s mouth because the artwork intends to confound the viewer with his immediate association with the image. Likewise, the MetaBirkin viewer instantly associates the image with the prestige of Hermès because Rothschild wanted to “create that same kind of illusion that [the Birkin bag] has in real life as a digital commodity.”107 The viewer may understand the gimmick within seconds or minutes of investigation, as Hermès’ paltry finding of only 18.7% consumer confusion demonstrates;108 yet the allure of the item does not fade even as the illusion does. The contemporary artist brings the buyer in on the cool irony that he is not actually acquiring a Birkin bag by purchasing an NFT of one, nor does he obtain a Campbell’s soup can by purchasing a silkscreen of one. Invoking the mark using similar references in order to pique consumer confusion is not only a bedrock example of trademark infringement but also the raison d’etre for the appeal of what Warhol describes as “business art,” including the MetaBirkins. The NFT represents the vehicle that accomplishes this illusion, because it is the medium of the NFT that accomplishes Breton’s “change of role” from handbag to digital artwork.

B. Convergence: Competitive Proximity and Bridging the Gap

The shared intuition behind the fourth and fifth prongs of the Polaroid test lies in the notion that, if the plaintiff and defendant generally sell the same types of products, it is more likely that the consumer will be confused and assume that the infringing product is connected with the plaintiff.109 The fifth prong of the Polaroid test considers the propensity for luxury fashion brands to “‘bridge the gap’ by moving into the NFT space.” It is prescient that the inspiration for Oppenheim’s tea-cup was a fur bracelet that she had crafted for an apparel designer, because as fine art has gravitated toward the consumer object, consumer brands have reciprocated in kind. The three other artists in Oppenheim and Breton’s serendipitous tale—Picasso, Dalí, and Miró—all helped to design wine branding in their own day, and the pop artist Jeff Koons followed in their footsteps by collaborating more recently with the champagne brand Dom Pérignon.110 Koons shares with Warhol a “factory-like studio” to create his works alongside a similar fascination with consumer brands.111 Louis Vuitton collaborated with Koons to put out a “Masters” collection that adapted the works of instrumental modern artists such as Van Gogh to the exterior of handbags and featured Koons’ own signature “bunny” as the shape for the bags’ accompanying leather bag fobs.112 Contemporary artist Yayoi Kusama has similarly worked with both Lancôme to design lip gloss and Louis Vuitton to decorate storefronts and produce fashion accessories, including handbags, which feature the same polka dot and pumpkins that distinguish her artistic repertoire.113 In light of these collaborations which thematically traverse the same consumerism-focused arena as contemporary art and feature motifs used by the artists in their fine art, fine art and designer fashion have competitively grown quite proximate according to the fifth prong of the Polaroid test.114

The fourth prong of the Polaroid test examines the “competitive proximity of the products in the marketplace.”115 Given the incentive for luxury brands to associate themselves with fine artists “to enhance their high-class products even further through their association with art and exclusivity irrespective of the substance of the art,”116 it only makes sense that luxury fashion brands would expand into NFTs. As discussed above, the MOMA has welcomed NFTs with an art exhibit that drew visitors to the museum and by participating in an NFT-collaboration with the same artist that featured digitally manipulated graphics of fine art in their museum collections. In turn, luxury brands have entered the NFT space in full-force, including Adidas, Prada, Gucci, Louis Vuitton, Nike, Burberry, Rebecca Minkoff, and Tiffany & Co.117 Unsurprisingly, then, Hermès alleged that “Rothschild’s project has disrupted their efforts to enter the NFT market and hindered its ability to profit in that space from the Birkin bag’s well-known reputation.”118 The more that art and fashion co-occupy the world of NFTs, the harder that it becomes for either party to lay claim to that territory. The broad convergence of art and fashion, in particular within the realm of NFTs, render the fourth and fifth prongs of the Polaroid test ill-equipped to separate knock-offs from fine art.

C. Choosing a Target: Strength, Sophistication, and Respective Quality

The first Polaroid prong evaluates the strength of the mark, as stronger marks merit greater protection. The seventh Polaroid prong considers the relative quality of the two marks, and the eighth Polaroid prong considers the sophistication of the consumers. As aforementioned, Hermès is a strong mark deserving greater protection. The MetaBirkin, which is new and unestablished, clearly riffs off the highly renowned quality of the older and historic Birkin mark; hence, the Birkin bag would likely be considered of greater “respective quality” than the MetaBirkin mark. In the framework of a conventional trademark infringement case, the first and seventh factors would strongly favor Hermès, for they would suggest that Rothschild has intended to profit off the goodwill of the senior brand. Perhaps the eighth Polaroid prong for the sophistication of the relevant consumers could cut in Rothschild’s favor on the basis of two assumptions: first, NFTs and Birkin bags are somewhat specialized, niche products, and second, anyone willing to spend thousands of dollars on either an NFT depicting a Birkin bag or a Birkin bag itself is likely knowledgeable of the cultural connotation of the object and the significance of the brand.

Moreover, for the highly sophisticated consumer of art and fashion, the layers of irony and commentary on commercialism evident in the MetaBirkin constitute the central appeal for acquiring such a costly digital object devoid of practical utility. When an artist such as Rothschild selects his target, he must choose an item with popular resonance and distort it in a way that will evoke the cool capitalist satire of Warhol’s soup cans. Consequently, he selected a product with widespread brand recognition—or a strong mark, the first Polaroid factor. Likewise, he chose an item of substantial respective quality to render his deflation of the item’s practical utility particularly biting—the seventh Polaroid factor. When artists borrow fashion influences for creative fodder, they necessarily must evoke well-known brands of high quality to ensure that the highly sophisticated consumers of their artwork will “get the joke,” so to speak.

As one MSCHF executive explained, “‘The Wavy Baby concept started with a Vans Old Skool sneaker’ because no other shoe embodies the dichotomies between ‘niche and mass taste, functional and trendy, utilitarian and frivolous’ as perfectly as the Old Skool.”119 To ensure that the satire of the Wavy Baby sneaker resonated with the consuming public, MSCHF needed to evoke a brand that itself held powerful connotations within the sneaker market. The Polaroid factors of strength of the mark and the respective quality of the marks demonstrate that the test for likelihood of confusion would ensnare virtually any work that invokes a famous brand to comment on consumerism; and yet, such a critique of a popular brand by the artist is exactly the reason why a sophisticated consumer would choose to acquire the item in the first place. In other words, if the infringed-upon mark is weak, if there is no difference in respective quality between the spin-off and the original, and if the consumers are unsophisticated, then the artistic message cannot land with the desired audience. As the courts have articulated in the context of the parody defense to trademark infringement claims, “the strength of a famous mark allows consumers immediately to perceive the target of the parody, while simultaneously allowing them to recognize the changes to the mark that make the parody funny or biting.”120 However nakedly mercenary his motivations were, Rothschild needed to comment on a strong brand like Hermès to sell a product that was of lower respective quality to a field of sophisticated consumers in order to make a successful artistic statement at all.

D. Bad Faith

The final Polaroid factor to consider is “whether Rothschild exhibited bad faith in using Hermès’ mark.”121 This factor seems to have been the most salient one to Judge Rakoff. In the court’s application of the first prong of Rogers, the court characterized the test for artistic relevance as depending in part upon an “unlawful intent to cash in.”122 Likewise, in the instructions that Judge Rakoff ultimately provided to the jury:

It must be clear to you by now that the parties disagree about the degree to which MetaBirkins NFTs are works of artistic expression … It is undisputed, however, that the MetaBirkins NFTs, including the associated images, are in at least some respects works of artistic expression, such as, for example, in their addition of a total fur covering to the Birkin bag images. Given that, Mr. Rothschild is protected from liability on any of Hermès’ claims unless Hermès proves by a preponderance of the evidence that Mr. Rothschild’s use of the Birkin mark was not just likely to confuse potential consumers but was intentionally designed to mislead potential consumers into believing that Hermès was associated with Mr. Rothschild’s MetaBirkins project. In other words, if Hermès proves that Mr. Rothschild actually intended to confuse potential consumers, he has waived any First Amendment protection.123

At trial, Judge Rakoff offered the following explanation for a preliminary version of his jury instructions:

Because while both Rogers and the related cases speak in, frankly, less than clear terms like “explicitly misleading” or “artistically relevant” and the like, the real question here, so far is the defense is concerned, is did Mr. Rothschild intend to mislead? In which case, of course, he has no First Amendment protection, any more than a con man has First Amendment protection from telling lies to the public to make money. Or did he not intend to mislead, in which case I think there can be no question that there was at least some artistic aspect to what he was offering.124

Rather than bad faith representing one of the eight factors in the second prong of a two-pronged test, the court in Hermès transformed bad faith into the focal point of the inquiry when determining whether Rothschild’s work merited First Amendment protection. As Judge Rakoff explained, his suggestion derives more generally from First Amendment doctrine and represents a more straightforward test that connects with other practices of law that focus on intent. It also falls in line with the Second Circuit’s longstanding posture that the factor of bad faith intent holds “great weight,”125 although the court in Hermès deviated from this precedent as well by using this factor to avoid marching through the Polaroid factors entirely.

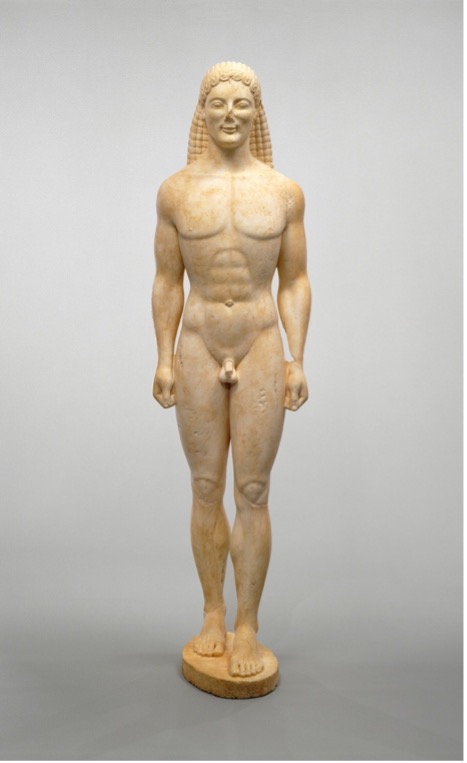

While Judge Rakoff correctly noted that the tests for artistic relevance and explicitly misleading prove fruitless where the entire purpose of the art form is to comment on consumer culture in a way that tricks the viewer, his line of inquiry falls into the same trap. Artists have moved between styles from archaic Greek kouros figures (Fig. 9)126 to Renaissance paintings to Jackson Pollock’s abstract expressionism (Fig. 10)127. These styles vacillate widely in how they depict what they see, or how they communicate “truth” to the viewer, by manipulating the subject of the image into a form that differs from how it is perceived in a photograph. Art depicts truth by bending it to the point of deceit. Dalí’s paintings bend time and space; he described this process as the “paralyzing tricks of eye-fooling … to systematize confusion and thus to help discredit completely the world of reality.”128 Rakoff’s “inten[t] to confuse potential consumers” cuts to the entire purpose of modern art, and the NFT is simply the latest iteration of this trajectory. As aforementioned, Rothschild intended to use the NFT to “create that same kind of illusion that [the Birkin bag] has in real life as a digital commodity.”129 The NFT constitutes the cornerstone to accomplish this sleight-of-hand—by offering up a flat digital commodity in lieu of a tactile physical good, in the same vein as the Dutch vanitas, it invariably represents the “con man” whom Rakoff wishes to outlaw.

Conclusion

To understand the unique challenge that the MetaBirkins pose to trademark enforcement as opposed to Warhol’s soup cans, we can distill two interrelated central issues of the works of art themselves. The first is content—where the chosen subject matter implicates the indicia of a famous brand, the artwork has the potential to infringe. The second is medium, which has the potential to either limit or exacerbate the likelihood that the consumer will experience confusion. The physical formulation of the Campbell’s soup cans as silk-screens on a wall in a museum limits the likelihood of consumer confusion because the viewer will immediately assume that two-dimensional images hung in art museums are works of art, whereas the MSCHF Wavy Baby sneaker collection exacerbates the potential for consumer confusion because consumers would assume that a sneaker bearing the trade dress of Vans sneakers is, in fact, a Vans-produced sneaker.130 The MetaBirkins fall somewhere in between these two poles, as both artists and fashion designers have attempted to claim the territory of the NFT as a medium for their craft.

The current Rogers balancing test attempts to account for both concerns: the “artistic relevance” prong considers the relevance of the trademark to the content of the artist’s message, while the “explicitly misleading” prong primarily evaluates whether the medium and its contextualization of the trademark facilitate the consumer’s understanding that this is an expressive work that riffs off the trademark, as opposed to the mark serving as an indicator of source. Unfortunately, the test ultimately fails to account for either and forces courts to answer a philosophical question of “art versus mark” at the outset with a reductive threshold inquiry; if anything, this note demonstrates that the art and fashion industries have rendered such a determination impossible because these two creative arenas see each other as entirely symbiotic and co-extensive. Preventing artists from using trademarks in their artwork would have a far-reaching chilling effect on free expression; imagine, for example, if magazine cartoon artists were cowed from making cartoons that featured famous trademarks when commenting on corporations’ activities.131 As opposed to regulating the content of expressive works, trademark law could simply allocate a safe-harbor for works of certain mediums that are more “traditional” to the art industry, such as paintings, sculptures, and films, and force others to answer to more stringent scrutiny.

The question of what constitutes art is an ancient one. The ancient Greeks classified all artwork as techne, meaning “craftsmanship.”132 Despite the current locus of the Greek pot behind glass in a museum and our modern appreciation for its beauty, it was originally a humble utilitarian object to store water, wine, or oil.133 The arbiters of the culture of ancient Greece applied the term techne with little discrimination between these household items and the statues artists carved carefully by hand.134 Our own distinctions between fine art, such as Heda’s Vanitas still-life, as opposed to decorative art, which could encompass anything from a visually attractive napkin-holder to a hand-painted mug, derive from the Latin ars.135 According to classical archaeologist Brian Sparkes, “The Roman elite, who collected so much Greek sculpture, seems not to have shown an equal interest in pottery.”136 The protections for trademarks rely on the artificial distinction between fine and decorative art that the Romans crafted to assert their subjective art-collecting preference for sculpture over pottery. The artistic lineage of the past century has explicitly challenged this separation, from Dalí’s advertising for consumer products to the Koons and Kusama handbag collections. This more contemporary strain of art history delights in the playground of the convergence of art and consumerism and propounds the notion that anything can be art.

To avoid evaluating the artistic merits of the content of a work—a subjective endeavor that would endanger free expression—the courts can opt to create a presumption that a distinction lies between fine art and craftsmanship as its threshold inquiry. As philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah explains, our “ideas about art … were not part of the cultural baggage of the people who made the objects” that he viewed on display at an exhibition of African art.137 Appiah explains that the objects in this exhibit “had primary functions that were, by our standards, non-aesthetic, and would have been assessed, first and foremost, by their ability to achieve those functions.”138 Such an investigation, which evaluates the artistic nature of the object by examining its medium, could function as an alternative threshold inquiry for the application of the Rogers test and would clarify much of the confusion about where fashion begins and art ends. The courts now pretend to abide by the ethos of the contemporary art movement that, in Warhol’s words, “art is what you can get away with” when they broadly define artwork to include new forms of media so long as the work “communicate[s] ideas” and “social messages … through features distinctive to the medium (such as the player’s interaction with the virtual world).”139 Yet in practice, they classify “[m]ovies, plays, books, and songs” as “indisputabl[e] works of artistic expression [that] deserve protection” and relegate knock-off sneakers to infringement.140 An explicit consideration of medium—and in particular, in the words of Appiah, whether the object is one that would be “assessed, first and foremost,” by its “primary … non-aesthetic” function—would allow courts to side-step such convoluted reasoning. Such a solution would grant artists greater certainty in predicting the legal consequences of their artwork as opposed to forcing them to gamble on the courts’ unpredictable interpretation of Rogers as it stands today.

Despite the increasingly close affinity between the art and fashion industries, the case of the MetaBirkins demonstrates that the battle between strong trademark protection and the promotion of free expression is zero-sum. The pre-Jack Daniel’s threshold inquiry into expressiveness tilted the balance in favor of artists, and the new threshold inquiry simply tips the scales in the opposite direction. Neither of these threshold inquiries, nor the actual Rogers test itself, properly account for the needs of both artists and consumer product brands. While the new threshold inquiry crafted by Kagan appears to fit into the commonsense ethos behind trademark law, it will also likely disqualify large swathes of expressive works that are considered quintessential examples of contemporary art, such as Warhol’s soup cans. If the Roman conceptualization of ars reveals anything, it is that classifying certain frontier objects as fashion rather than art would uphold the principles of art history rather than betray them. Regardless of whether a safe-harbor for works of certain mediums proves a viable solution, artists require a more predictable understanding of whether their work is protected under the First Amendment or subject to trademark infringement scrutiny to practice their craft.

The collision of art and fashion has rendered any attempt to separate art from marks exceptionally messy, and in crafting a solution, we must choose from the best of a number of destructive options, any of which would cede territory from one industry and grant it to the other. Evaluation of medium might prove highly suppressive to large swathes of creativity in the art world and force a rupture between art and fashion that neither industry desires; it could force the courts to craft somewhat fuzzy distinctions between, for example, a mug that serves as merchandise and a ceramic work of fine art. Alternatively, perhaps an explicit consideration of medium would change almost nothing about the actual outcomes of trademark-infringement lawsuits, as courts quietly use the medium to smooth over their application of the Rogers test even today. The Polaroid factor for the “similarity” between the products evidently considers medium, albeit under the guise of evaluating similarities in the trade dress between the items; for example, the MSCHF court belabored the similarities between the toe box and other shared elements of the Wavy Baby and Vans sneakers.141 Likewise, when courts consider the “competitive proximity” and the likelihood of the plaintiffs “bridging the gap,” they essentially ask whether the plaintiffs produce the same type of product142—goods that express not merely the same message but also the same message through the same medium. For example, the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California recently considered a line of NFTs that copied elements of an infamous rival set of NFTs called the “Bored Ape Yacht Club” collection and concluded that the shared NFT medium between the two goods weighed in favor of a finding of infringement.143

A stronger and more predictable standard for separating artwork from consumer goods, such as classification by medium, would likewise serve the core purpose of trademark law. Trademark expert Barton Beebe frames trademark law as an exercise in semiotics and explains the three constitutive elements of “the triadic structure” as follows:

First, the trademark must take the form of a “tangible symbol.” This “word, name, symbol or device or any combination thereof” constitutes the trademark’s signifier … Second, the trademark must be used in commerce to refer to goods or services. These goods or services constitute the trademark’s referent … Third and finally, the trademark must “identify and distinguish” its referent. Typically, it does so by identifying the referent with a specific source and that source’s goodwill. This source and its goodwill constitute the trademark’s signified. Thus, in the case of a trademark such as NIKE, the signifier is the word “nike,” the signified is the goodwill of Nike, Inc., and the referent is the shoes or other athletic gear to which the “nike” signifier is attached … To maintain the structural integrity of the mark, the law does not merely enforce linkages among the mark’s three elements. It also enforces separations among them. The mark’s elements must be related, but they may not be identical.144

To adapt Beebe’s language to the case of Hermès, the signifier is the word “Birkin,” the signified is the goodwill toward Hermès and the Birkin brand, and the referent is the particular handbag to which the signifier “Birkin” is attached. Each of these elements is connected, but they are not identical to each other. The MetaBirkin erodes the connection between the “signified” and the “referent” because the NFT offers only the goodwill of the Birkin brand without the bag itself. Luxury brands, though, are also responsible for this breakdown. When the realms of fine art and fashion commingle freely in the space of NFTs and the referent for the word “Birkin” expands from handbags to include NFTs and products equipped for the metaverse, the vital separations between the signifier, the signified, and the referent that “maintain the structural integrity of the mark” disintegrate. To allow artists and fashion brands alike to function, the jurisprudence must craft clear boundaries between artworks and consumer products.

On February 8, 2023, the jury in Hermès ultimately found Rothschild liable for trademark infringement and determined that the NFTs did not constitute protected artistic expression under the First Amendment. Subsequently, the court in Hermès awarded $133,000 in damages to Hermès;145 Rothschild has appealed the judgment.146 As it stands, the jury’s determination in Hermès poses concerning ramifications for freedom of artistic expression and the entire realm of Warhol’s “business art,” and the convergence of luxury fashion and fine art does not bode well for the future of trademark doctrine. Kagan’s tautological inquiry into whether the mark is acting like a mark accomplishes little by way of clarifying this distinction; it simply tips the balance in favor of finding infringement as opposed to artistic expression.

The lineage of art preceding the MetaBirkins, including Dutch vanitas, Monet’s cathedrals, Oppenheim’s furry teacup, and Warhol’s soup cans—in tandem with collaborations between luxury fashion brands and contemporary artists—demonstrate that the growing interest among artists in their own status as market participants rendered this collision between art and fashion inevitable. That NFTs were born already occupying this space between art, commodity, and investment contract rendered them the ideal situs of the battleground between contemporary art and luxury fashion. As luxury brands and fine art converge more broadly, NFTs will likely represent only one of many arenas in which the Rogers test will need to weigh the more substantial interest between the property rights of fashion brands’ goodwill and freedom of expression for artists. The inability of the Rogers test to cut to Breton’s “Crisis of the Object” that underlies both the MetaBirkins and the general trajectory of contemporary art forebodes the future challenges at the intersection of art and fashion that the test will surely face as the two industries continue to converge.