Taorui Guan *

Download a PDF version of this article here.

In the era of digitization, data has become a pivotal force driving advancements across various sectors and transforming legal systems worldwide. China, in particular, is exploring new data-driven governance models. A prime example of this is its integration of the patent system with the Social Credit System (SCS). This paper aims to fill the void in theoretical research on this subject, moving beyond the prevalent narrative of the SCS as either a tool of state surveillance or a reputation-based regulatory mechanism. Instead, it introduces the concept of personalized law in the context of China’s patent system.

The paper suggests that the integration of social credit data within China’s patent law system aligns the system’s operations more closely with its objectives. This offers a personalized approach that provides individual market entities with tailored incentives based on their unique characteristics. To analyze this approach, the paper proposes a novel four-part analytical framework: profiling, personalization, communication, and adjustment. The paper then applies this framework to the two core mechanisms that result from the integration of the patent system with the SCS: the Reward and Punishment Mechanism and the Tiered Regulation Mechanism. This analysis reveals that these mechanisms are still in the stage of crude personalization and grapples with challenges such as narrow data scope, lack of transparency, and over-penalization.

The paper discusses two implications of personalized law reform: the redistribution of power toward administrative bodies—which necessitates a rebalancing of powers to avoid abuse and protect individual rights—and the possible expansion of the law’s functions—which might not align with existing normative theories and might have unintended consequences. The process of personalization requires scholars and policymakers to adapt and refine these theories as well as to identify and eliminate unintended consequences.

Introduction

In the digital age, the increasing prominence of data is reshaping diverse fields beyond the realm of technology, influencing commercial practices and the foundations of governance.1 In the legal sector, this shift is evident as governments employ data to enhance the operation of their legal systems.2 The response to the COVID-19 pandemic exemplified the pivotal role of data, where law enforcement strategies informed by real-time data were instrumental in addressing public health challenges.3 Such scenarios illustrate the burgeoning trend of integrating data analytics into legal and governance frameworks,4 establishing data-driven laws as an imminent reality.5 China’s adoption of the Social Credit System (SCS) within its legal framework, utilizing social credit data for dynamic insights into behaviors,6 marks a significant stride in this global movement.

The broader applications of China’s SCS and its data-driven paradigm have increasingly gained scholarly attention.7 However, a specific and critical area remains less explored: the integration of the SCS within patent law, particularly through the implementation of two key mechanisms—the Reward and Punishment Mechanism8 and the Tiered Regulation Mechanism.9 Introduced through the State Council’s 2014 initiative for “credit construction in intellectual property,” these mechanisms represent a pioneering approach to melding social credit data with the operation of the patent system.10 This strategic integration of the Reward and Punishment Mechanism and the Tiered Regulation Mechanism, crystallized in the 2019 Regulation on Management of the List of Joint Punishments for Seriously Untrustworthy Entities in the Patent Field (Trial), reflects China’s commitment to enhancing intellectual property laws and curbing infringement using data-driven methods.11 Studying this integration is crucial, as it exemplifies the evolution of a legal regime of property into a data-driven domain, offering a distinctive example of how legal systems can be transformed through the application of data analysis.

Existing literature primarily oscillates between portraying the SCS as a tool for state surveillance and as a model for reputation-based regulation.12 However, these interpretations do not fully capture the essence of the Reward and Punishment Mechanism and Tiered Regulation Mechanism within the realm of patent law. Scholars like Nicholas Loubere, Stefan Brehm,13 and Fan Liang14 depict the SCS as surveillance infrastructure, integral to state control and the maintenance of stability. This narrative, which Lauren Yu-Hsin Lin and Curtis J. Milhaupt developed further under the concept of “surveillance state capitalism,” regards the SCS as a tool for monitoring and controlling economic actors, enhancing corporate compliance, and aligning market behavior with the political objectives of the Chinese Communist Party.15 Anne S.Y. Cheung and Yongxi Chen have further developed this perspective, portraying the SCS as a mechanism that could transform China into a “data state.”16 In this data state, the government would use data collection and data-driven methods extensively to monitor, assess, and regulate the behavior of its citizens.17 Scholars holding this view generally believe that the integration of SCS with the legal system is likely to have undesirable consequences, including curtailing individual autonomy,18 infringing on human rights,19 and undermining the principles of the rule of law.20

However, framing the SCS solely as an instrument for consolidating state power does not reflect its actual application and impact. While there are legitimate concerns surrounding privacy and security risks associated with the SCS, Xin Dai suggests that focusing exclusively on these aspects may overlook the system’s potential to advance China’s regulatory regimes.21 The alignment of the SCS with policies like “streamlining administration, delegating powers, and improving services”22 indicates a move away from stringent governmental oversight, as evidenced by reduced state oversight in certain domains.23 This contradicts the concerns about heightened control. Furthermore, a national survey showing over 80% of China’s connected population engaging with the SCS and acknowledging its positive role in promoting accountability, regulations adherence, and quality of life,24 suggests that the perceptions of the SCS are varied and may be influenced by its integration into various facets of governance, likely including those that streamline and improve administrative services.

Dai’s alternative perspective views the integration of SCS into the legal system as the introduction of a reputation-based regulatory model that relies on social credit data. In this context, the SCS employs mechanisms like blacklisting and scoring in response to a range of governance issues, from market deception to government misconduct.25 While these mechanisms might resemble aspects of state surveillance, the primary focus of a reputation-based state is on encouraging compliance and self-discipline through reputational incentives, rather than on pervasive monitoring and control. Echoing this view, Daithí Mac Síthigh and Mathias Siems note that the SCS has facilitated China’s transition from a “reputation society” to a “reputation state.”26 This perspective effectively captures the integration of the SCS with legal frameworks.

However, focusing solely on the reputation aspect does not adequately capture the entire spectrum of the SCS’s implications for patent law. The Reward and Punishment Mechanism and the Tiered Regulation Mechanism extend beyond reputational impact to substantive economic consequences such as limiting access to finance and constraining operational activities.27 Cheung and Chen observe that the concept of “credit” in this context is becoming increasingly complex.28 The SCS employs a broad range of data, moving away from a strict association with individual or corporate reputation and toward a broader set of attributes and behaviors.29 This evolution in the scope and application of data calls for a more comprehensive analytical framework through which to understand the integration of the SCS with patent law.30

This paper proposes that we can understand the integration of social credit data in China’s patent law more comprehensively through the concept of “personalized law” that Omri Ben-Shahar and Ariel Porat have developed.31 Personalized law systems tailor legal rules to individual circumstances rather than applying uniform rules in every case.32 Although theoretical discussion of personalized law spans a range of legal domains, from traffic regulations33 to consumer protection,34 there has been little practical implementation.35 This paper suggests that the integration of the patent system with the SCS is an example of this concept, and that it marks a significant step toward the application of personalized law.36 Viewing the Reward and Punishment Mechanism and the Tiered Regulation Mechanism as forms of personalized law not only enriches our understanding of the nuanced interplay between social credit data and the patent system, but also highlights the potential of personalized law to transform legal systems in a technologically advanced and contextually relevant manner.37

Part I of this paper delves into the practical challenges confronting China’s patent law and theoretical underpinnings of its integration with the SCS. There are two primary obstacles impeding the effectiveness of the patent system in promoting innovation: the rise of speculative patent applications and the inadequacy of the system’s remedies for infringement.38 The Reward and Punishment Mechanism and the Tiered Regulation Mechanism address these challenges by allowing the patent system to incorporate social credit data strategically. Through the use of social credit data, these mechanisms personalize the rules of the patent system, aligning operations more closely with its function of incentivizing genuine innovation and effective knowledge dissemination, thereby mitigating the limitations of the traditional, one-size-fits-all approach.39 Presently, this model exemplifies the crude personalization phase of personalized law as outlined by Ben-Shahar and Porat, which involves forming “discrete buckets of treatment” based on individual characteristics and applying these treatments accordingly, moving away from a uniform approach to more nuanced and individualized legal applications.40

In Part II, this paper presents a comprehensive analysis of the Reward and Punishment Mechanism and the Tiered Regulation Mechanism of China’s patent system, utilizing a novel analytical framework derived from personalized law literature. This framework—comprised of profiling rules, personalized rules, communication rules, and adjustment rules—serves as a tool for dissecting and understanding these mechanisms as forms of crude personalized law.41 Applying this framework, this paper highlights the mechanisms’ intricacies and implications, demonstrating that they function as manifestations of personalized law, and evaluating their effectiveness and challenges.42

Part III of this paper explores the profound implications of personalizing patent law with social credit data. This section describes how personalized law shifts the balance of power within the state, enhancing the role of administrative bodies.43 It discusses the need for enhanced legislative, judicial, and public engagement mechanisms to balance this shift.44 Additionally, Part III examines how personalized law can expand the functions of patent law—from fostering innovation to promoting a compliant and disciplined market environment.45 This functional expansion highlights the need for reevaluation of existing legal theories and normative justifications of patent law, as well as for meticulous appraisal of the resultant societal impacts, emphasizing the necessity of academic engagement to provide robust descriptive and normative frameworks for the evaluation of legal functions in an age of personalized law.46

This paper contributes to the literature in three significant ways. First, it provides an alternative—and potentially more fitting—theoretical perspective on the current integration of social credit data in China’s patent law. This perspective is crucial, as it enhances our understanding of how law is changing in the context of advanced data systems and digital governance.47 Moreover, on a practical level, the analysis of personalized patent law not only aids domestic entities in China but also provides valuable insights for enterprises operating in the Chinese market from foreign countries, including the United States.48 Second, the paper provides an example of personalized law in practice. This is particularly noteworthy as the field of personalized law lacks substantial real-world applications.49 This, then, is a valuable case study, which sheds light on the potential effects of personalized law, particularly on the distribution of powers and the expanding roles and objectives of legal systems. Third, this paper pioneers an analytical framework that advances the understanding of personalized law. The novelty of this framework lies in its application to the “crude” stage of personalized law, which has not yet engaged with Big Data and algorithms. This framework would assist scholars and practitioners in comprehending the operations and impacts of personalized law during its developmental phase or as it transitions to more advanced stages.

I. Toward Personalized Patent Law

A. Patent Law Faces Two Challenges

The patent system seeks to promote innovation.50 It does this in two ways. First, it awards inventors exclusive rights to their discoveries.51 This exclusivity gives them the ability to derive financial rewards from their inventions.52 Having exclusive rights allows creators to demand substantially greater prices for their products than would be feasible in a competitive marketplace,53 which encourages creators to invent.54 Second, rooted in the disclosure theory,55 it makes the inventions’ technical information accessible to the public.56 With the details of patented inventions, the public can enhance, modify, or freely employ these inventions after the patents expire.57

China’s patent system faces two significant challenges in fulfilling its incentive and disclosure functions. The first arises from the prevalence of speculative patent applications.58 These speculative patent applications, often of low technical quality, stem not from a genuine need for innovation protection but rather from the desire to exploit the exclusivity of patent rights for profit.59 Patent agencies and attorneys who, motivated by financial gains—including government subsidies for application fees—encourage and support the submission of these low-quality patents exacerbate the problem.60 Such opportunistic behavior has led to an influx of inferior patents into the system, creating a “patent bubble.”61

These speculative applications, along with the complicit actions of the patent agencies and attorneys, obstruct the objective of patent law—promoting innovation. Patents derived from speculative applications fail to serve the system’s intended purpose of protecting the interests of genuine creators. Instead, they are often used as tools to improperly obtain financial benefits, such as government subsidies or tax breaks, without contributing to actual innovation.62 Moreover, they consume valuable examination resources, leading to longer processing times for substantial and innovative patent applications and potentially hindering true innovators from receiving timely rewards.63 The proliferation of low-quality patents also impedes researchers and businesses in their technological research searches, which undercuts the patent system’s goal of disseminating knowledge.64

The second challenge pertains to the inadequacy of remedies for patent infringement.65 Patent holders in China often experience extended delays before receiving court judgments, particularly in cases involving foreign parties.66 Zhang Chenguo’s empirical research shows these cases take an average of 11.7 months, with some extending to 63.3 months, far exceeding the statutory six-month limit.67 In infringement cases, rights holders struggle to gather sufficient evidence,68 and courts often award damages that are significantly lower than claimed.69 For instance, in the city of Nanjing, courts typically award only about 40.7% of the claimed damages.70 Enforcement of judgments also presents challenges,71 exacerbating the issue of insufficient remedies. Between 2008 and 2012, over 70% of judgment debtors in national courts attempted to evade, avoid, or even violently resist enforcement.72 This judicial inefficiency encourages opportunistic and repeated infringements. Insufficient compensation and frequent infringements both diminish innovators’ incentives for innovation and discourage them from disclosing their technology through patents.

B. Personalization of Patent Law as a Solution

To address the challenges of speculative patent applications and inadequate remedies for patent infringement, the Chinese government introduced two mechanisms into its patent law: the Reward and Punishment Mechanism and the Tiered Regulation Mechanism, both of which rely on social credit data. This paper posits that these mechanisms reflect an overarching strategy to personalize the rules in the legal system, aligning its operation more closely with its objectives. In the context of patent law, this means tailoring the rules in the patent system to improve its fostering of innovation and dissemination of knowledge,73 or at least to correct the system where it currently deviates from these objectives.

Personalization enhances the precision of legal rules by tailoring them to individual circumstances, characteristics, or behaviors,74 as opposed to applying one-size-fits-all rules. Advocates of personalized law argue that uniform rules might be “good on average” but they often do not adequately cater to entities with diverse traits,75 as they are potentially both “over- and under-inclusive.”76

In theory, personalized law can apply to a broad range of legal domains, such as traffic regulations,77 negligence,78 criminal procedure,79 contracts,80 copyrights,81 consumer protection,82 data privacy,83 and pre-commitments.84 A ubiquitous example in academic discussions is personalized traffic regulations, where speed limits are customized based on the distinct characteristics of each driver.85 Under such a framework, drivers with varying risk profiles would face different legal rules even in identical external conditions. This nuanced personalization of traffic laws considers various factors that contribute to a driver’s risk level.86 For example, it might classify a driver with a history of accidents as high-risk and would consequently assign him more conservative speed limits. In contrast, those with a clean driving record might be permitted to drive at higher speeds. This aligns the legal framework more closely with the objective of reducing road accidents by holding high-risk drivers to stricter standards. The sophistication of such personalized traffic regulations can be enhanced by leveraging Big Data and algorithmic analysis.87 This would allow for the formulation of highly individualized speed limits based on an array of personal attributes, including a driver’s eyesight, reaction instincts, driving experience, and even real-time measures of fatigue.88 Additionally, the algorithmic model could incorporate factors like age, sex, and credit score, which actuarial models often associate with driving risk.89 This level of detail would ensure that each driver’s speed limit is optimized based on a comprehensive assessment, thereby contributing to safer traffic management.

Similarly, in the patent law context, personalized rules could subject entities with a history of filing speculative patent applications or engaging in intentional or repeated infringements to more stringent oversight or potent counter-incentives. Conversely, entities whose actions align with the goals of the patent law system could receive positive incentives, encouraging them to maintain or even elevate their standards of operation in ways that better advance the patent system’s goals.90

Data plays a crucial role in enabling this personalization.91 Without data, the government could not discern individual traits and craft tailored rules that would allow it to achieve its legal objectives more effectively.92 The Reward and Punishment Mechanism of China’s patent system classifies entities into categories based on their social credit data, which indicates whether they are “trustworthy” or “untrustworthy,” and applies corresponding incentives in the forms of rewards or punishments.93 The Tiered Regulation Mechanism, on the other hand, assesses entities based on their social credit scores, assigning them ratings that dictate the level of regulation they receive.94 This differentiated approach allows the government to tailor its rules more finely.

In the realm of personalized law, scholars recognize different degrees of personalization, ranging from more sophisticated to more rudimentary. High-degree personalization involves the use of large datasets and algorithmic analysis to generate rules based on individual traits, situational contexts, and legal objectives.95 Casey and Niblett refer to these as “microdirectives,” or highly precise rules.96 When the system cannot attain this level of detail, it uses a more preliminary approach—crude personalization.97 According to Ben-Shahar and Porat, crude personalization in law means forming “discrete buckets of treatment” based on individual characteristics, and applying these treatments accordingly.98 They suggest that “much of the benefit” of personalized law “could be achieved this way.”99 Currently, both the Reward and Punishment Mechanism and the Tiered Regulation Mechanism in China’s patent system represent this form of crude personalization.100

A typical example of crude personalization in law in the academic discourse is the personalized alcohol purchase age.101 Instead of applying a uniform age requirement, such as 21, the legal system could implement a stratified approach that reflects varying risk levels of alcohol abuse among individuals. This model could avoid reliance on highly sensitive information like mental health records.102 Instead, a stratified approach could use more general data to determine risk categories. For instance, this might allow individuals deemed least risky, based on factors such as driving records and evidence of risk-seeking behavior, to purchase alcohol at age 18.103 It might set the legal purchase age at 20 for those with a moderate risk level, while the system might restrict the highest risk individuals until age 22.104 This method of categorization would utilize less intrusive data while still attempting to tailor legal obligations to individuals’ idiosyncratic risks and behaviors.

II. Analysis

To understand the Reward and Punishment Mechanism and the Tiered Regulation Mechanism within China’s patent system as a crude form of personalized law, we need an analytical framework. Since no studies have yet provided such a framework, this paper proposes one by synthesizing insights from personalized law literature. While scholars initially proposed many of these insights in the context of advanced stages of personalized law that is based on Big Data and algorithms, they apply equally to the analysis of its crude form. Utilizing this framework, the paper delves into a detailed analysis and assessment of both mechanisms.

A. An Analytical Framework

The essence of personalized law lies in providing different rules for different individuals. However, to sustain this system, merely having personalized rules is insufficient. This paper categorizes the rules in personalized law into four types, by function: profiling rules, personalized rules, communication rules, and adjustment rules.

Profiling rules: The personalization of rules relies on identifying the characteristics of regulated entities.105 Therefore, in a personalized law system, there must be rules outlining how the government may use data to create individuals’ profiles.106 We can call these “profiling rules.” Profiling rules must address several issues. First, they need to specify the entities responsible for data collection.107 Elkin-Koren and Gal note that this can involve government-collected data, such as from speeding cameras and tax returns, and data that private firms collect, such as from wearable technology or smartphones.108 Where government data is inadequate, a blend of governmental and private data sources might be necessary in order to craft effective personalized laws.109 Second, profiling rules must address the scope of the data collection. A broad scope can be advantageous, as more data facilitates the formation of detailed and accurate profiles.110 However, factors such as collection cost, the capacity of data processing, and the need to protect privacy limit its scope.111 Third, profiling rules also need to control the formation of profiles, ensuring that the government can derive meaningful conclusions from the collected data.112 An example is Adam Davidson’s discussion of using data to identify “the dangerous few”—those most likely to re-offend.113 In this context, the essence of a profile lies in its practical application: pinpointing “the dangerous few” informs tailored approaches, such as specific incarceration or surveillance measures.114

Personalized Rules: Personalized rules are the crux of personalized law. The government can generate them algorithmically, including through AI, based on the collected data, to ensure alignment with the system’s objectives.115 However, infinitely increasing precision in personalization is impractical due to cost and technical constraints.116 A more feasible alternative is crude personalization, where the government creates discrete buckets of treatment based on broad profiles, and imposes them accordingly.117 While this approach reduces precision, it also curtails the costs of data collection and decreases reliance on algorithms.118 Personalized rules fall into two categories—unilateral and bilateral.119 Unilateral personalization, the simpler type, addresses the interests of a single party.120 We see this in scenarios such as customizing regulations to individual consumer needs in consumer protection laws or tailoring the preferences of a testator.121 Bilateral personalization involves balancing the interests of two parties, as occurs in contract law.122 This approach recognizes the intricacies and price sensitivities involved in adjusting legal parameters like warranty periods, depending on each party’s unique characteristics.123

Communication Rules: The way that the government communicates personalized rules to the relevant entities is critical. This paper defines the strictures governing this process as “communication rules.” A vital aspect of these rules is the timing of their communication. Generally, the government should communicate an entity’s personalized rules before it undertakes relevant actions, enabling the entity to adjust its behavior.124 The communication can be immediate or non-immediate. Immediate communication uses technology to relay rules to individuals just before they act.125 Non-immediate communication allows for the dissemination of rules in advance, giving entities sufficient time to understand and integrate these norms into their decision-making processes, and avoids the potential pitfalls of haste.126 This is particularly applicable to circumstances where real-time behavior adjustment is not necessary.

Adjustment Rules: Adjustment rules regulate or correct both the outcomes and the formulation of the aforementioned rules. Adjustment rules are essential for maintaining the integrity of the personalized law system and for safeguarding the rights of those regulated. Ben-Shahar and Porat’s discussion highlights the importance of these rules, arguing that personalized law, as a departure from “the uniformity of rules,” means stepping into challenging territories where “things could go wrong in many ways.”127 The government should “regularly audit” personalized rules and actively “identify and correct unintended effects.”128 While scholars agree on the need for this adjustment mechanism,129 they raise concerns over its effectiveness as personalized law evolves, particularly when the government uses algorithms to generate rules.130 In this case, the rules’ complexity and sophistication might surpass human understanding, which makes it difficult to identify and address errors.131

B. The Reward and Punishment Mechanism

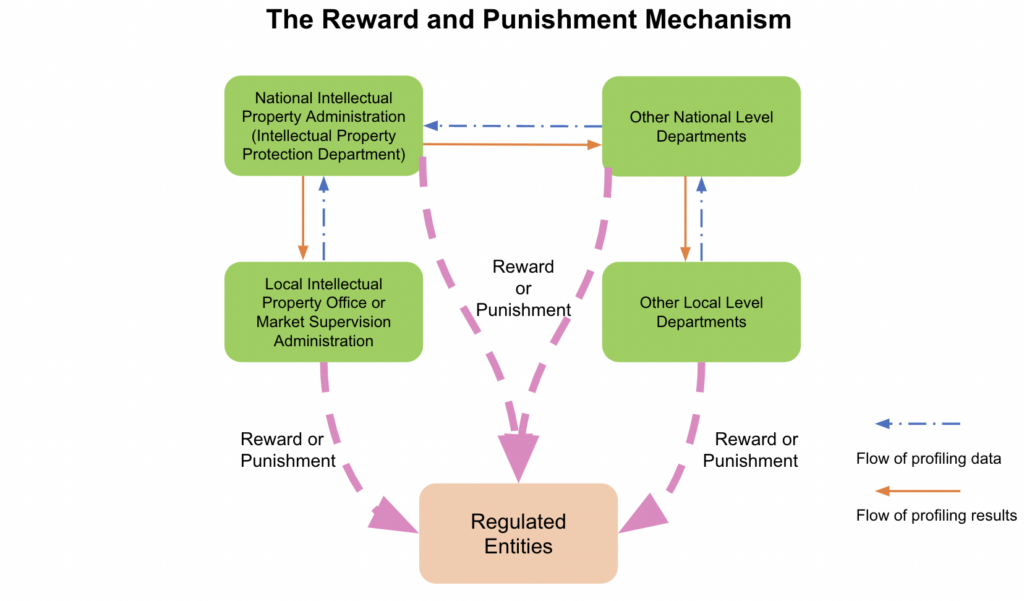

The Reward and Punishment Mechanism in China’s patent law operates on the principle that governmental entities apply rewards or sanctions based on the profiles of individuals or enterprises. This approach is not limited to patents but extends to other sectors like taxation and environmental protection.132 Currently, two departmental regulations—The National Intellectual Property Administration’s Intellectual Property Credit Management Regulations (“Credit Management Regulations”)133 and The Market Supervision Administration’s Management Methods for the Serious Illegal and Untrustworthy Entity List (“Untrustworthy Entities Management Methods”)134—govern the reward and punishment mechanism in the patent domain. The following diagram helps to illustrate this mechanism’s structure and functionality.

Figure 1 illustrates the structure and key components of the Reward and Punishment Mechanism in China’s patent law. The central component is the Intellectual Property Protection Department (IP Protection Department), which aggregates social credit data and creates profiles of regulated entities.135 The IP Protection Department aggregates data collected by other departments responsible for patent-related work and patent agency regulation.136 Based on this data, the IP Protection Department categorizes entities into three profiles: “Untrustworthy Entities,” “Seriously Illegal and Untrustworthy Entities,” and “Entities with Good Credit for Three Consecutive Years.”137 The first two profiles are associated with various punitive measures, while the last profile qualifies entities for rewards. The specific punitive measures and rewards are predetermined and officially declared to the public.

1. Profiling Rules

The Reward and Punishment Mechanism primarily collects data through government channels. The National Intellectual Property Administration, particularly the IP Protection Department, is at the core of this mechanism.138 Other departments responsible for patent-related work and patent agency regulation also contribute to data collection.139 These departments collect data during their “execution of statutory duties and provision of public services” and report to the IP Protection Department.140 Currently, the scope of data collection in the patent field is relatively narrow, limited to data concerning an entity’s specific types of legal violations.141 Categorization in either of the first two categories (“Untrustworthy Entities” and “Seriously Illegal and Untrustworthy Entities”) can lead to sanctions,142 while the last category (“Entities with Good Credit for Three Consecutive Years”) opens opportunities for rewards.143

To label an individual or enterprise as an “Untrustworthy Entity,” the IP Protection Department must identify at least one act of “untrustworthy conduct.”144 Strict rules govern the recording of untrustworthy conduct data, limiting records to legally effective documents such as notices of abnormal patent application rejection, administrative penalty decisions for illegal patent agency activities, and decisions or penalties recognizing refusal or evasion of execution despite having the ability to comply.145 Article 6 of the Credit Management Regulations enumerates six categories of untrustworthy conduct, mostly related to patents. These include abnormal patent applications not aimed at protecting innovation, activities in patent agencies that violate laws or administrative regulations and result in administrative penalties, and actions involving the refusal to execute or the evasion of administrative penalties or decisions despite having the ability to comply.146 These categories are not exhaustive, and the IP Protection Department can deem other behaviors untrustworthy as well.147

To categorize an individual or enterprise as a “Seriously Illegal and Untrustworthy Entity,” the IP Protection Department relies on four types of information.148 First, records of having engaged in seriously illegal patent agency activities coupled with having received “relatively heavy administrative penalties,” such as fines or license revocation.149 Second, records of having refused to execute administrative decisions despite having the ability to comply, along with findings that such behavior significantly undermines the credibility of the National Intellectual Property Administration.150 Third, a history of intentional patent infringement, along with heavier administrative punishment from the departments for market regulation.151 And fourth, being identified as having submitted abnormal or malicious patent applications, with an official determination that these applications harm the public interest.152

In contrast to the IP Protection Department’s identification of “Untrustworthy Entities” and “Seriously Illegal and Untrustworthy Entities,” there is no established list of “Entities with Good Credit for Three Consecutive Years” under Article 20 of the Credit Management Regulations.153 Consequently, entities believing they fit this category must declare their status in order to claim government-provided benefits.154 At present, entities petitioning for this status must demonstrate that they have operated for three consecutive years without garnering negative credit information.155 In practical terms, departments responsible for administering incentives only need to confirm the absence of negative credit records in the social credit system’s database.156

2. Personalized Rules

Currently, the personalization approach in China’s patent system represents a form of crude personalization.157 In other words, the government sorts individuals and enterprises into broad categories based on their profiles and applies corresponding sets of rules to each category. Article 9 of the Credit Management Regulations outlines six distinct punitive measures,158 which we can put into four categories. The first increases the difficulty of obtaining benefits from the government, such as requiring stringent approval for government-funded projects and for preferential policies related to patent applications.159 The second involves the withdrawal of eligibility for certain benefits, including disqualification from recognition as a “National Intellectual Property Demonstration and Advantage Enterprise” and from receiving the “China Patent Award.”160 The third provides for intensified regulatory oversight, such as more frequent inspections.161 The fourth revokes the privilege of utilizing the “credit commitment system,” which simplifies administrative procedures for entities with a positive credit standing.162 Importantly, while Article 9 states these measures explicitly, it also allows for the imposition of other measures according to the relevant laws, administrative regulations, and policies of the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the State Council.163

The restrictions for “Seriously Illegal and Untrustworthy Entities” are broader and more critical than those for “Untrustworthy Entities,” especially with respect to basic operational and market participation permissions. Similar to “Untrustworthy Entities,” “Seriously Illegal and Untrustworthy Entities” receive more regulatory oversight, with more frequent inspections and strict monitoring.164 These entities lose the opportunity to utilize the notice and pledge system,165 which streamlines the processing of administrative matters.166 In addition, entities in this category face up to 38 punitive measures implemented by multiple government departments.167 These 38 measures include restrictions on stock market financing, internet information services, and participation in public resource transactions—all significantly limiting the commercial activities and operations of relevant entities.168

In contrast to these punitive measures, “Entities with Good Credit for Three Consecutive Years” receive a set of beneficial personalized rules.169 However, such benefits are not guaranteed, as administrative authorities retain discretion in awarding them.170 According to Article 20 of the Credit Management Regulations, there are four categories of benefits: first, prioritization in the administrative approval processes, such as expedited processing; second, greater ease in securing government grants; third, right of access to expedited patent examination processes; and fourth, fewer inspections.171 Administrative authorities can implement other incentive measures as well.172 However, the scope of benefits for entities in this category is limited to the purview and services of the departments and units of the State Intellectual Property Administration,173 which might not be attractive to entities whose business substantially relies on matters other than IP.

3. Communication Rules

In the current framework of China’s Reward and Punishment Mechanism, administrative agencies do not generate personalized rules in real time. Instead, they pre-formulate them. The Credit Management Regulations and the Untrustworthy Entities Management Methods detail the relevant rules and make them publicly accessible, as they do for statutory laws.174 Though this approach provides a complete set of personalized rules, these rules possess inherent informational gaps, as evidenced by administrative bodies’ open-ended listings and discretionary enforcement.175 For instance, an entity has no guarantee that it will receive the benefits for “Entities with Good Credit for Three Consecutive Years,” as these are subject to the agencies’ discretion.176 Therefore, even with access to the rules, it is difficult for individual entities to grasp the full extent and legal consequences of their personalized rules.

Although it should precede an entity’s action, the communication of these rules is not instant. Unlike the theoretical, immediate relay of personalized speed limits, there is no temporal proximity between an agency’s rule communication and the relevant entity’s subsequent actions. Additionally, when an entity qualifies for this “good credit” category, there is no direct communication with the entity itself currently. The lack of communication means that entities must instead rely on their knowledge to determine that they qualify for benefits. In contrast, for “Untrustworthy Entities,” public announcements act as the notification mechanism, and the IP Protection Department publishes the list of untrustworthy entities on the State Intellectual Property Administration’s website.177 The system for “Seriously Illegal and Untrustworthy Entities” involves two layers of communication: preliminary notification of the basis for the decision basis before an entity’s inclusion on the list,178 and then public disclosure on government websites and the national enterprise credit information system.179

The public disclosure of “Untrustworthy Entities” and “Seriously Illegal and Untrustworthy Entities” lists is a form of public shaming that affects the entities’ reputation and potentially disrupts their social and commercial interactions.180 This public portrayal can diminish the confidence of their clients, partners, and investors, limiting their business opportunities and their ability to establish financial relationships.181 Therefore, the communication about disclosure on government websites can be insufficient to correct behavior, as entities’ reputations will already be tarnished.182

4. Adjustment Rules

In the existing structure of China’s Reward and Punishment Mechanism, adjustment rules are critical for protecting the rights of those labeled as “Untrustworthy Entities” or “Seriously Illegal and Untrustworthy Entities.” These adjustment rules are twofold: duration regulations and error correction protocols.

Regarding duration, the punitive measures applied to “Untrustworthy Entities” and “Seriously Illegal and Untrustworthy Entities” have specific time limits.183 Measures against “Untrustworthy Entities” typically last for one year, but can be extended by up to three years if the IP Protection Department discovers new data about the entity’s untrustworthy conduct.184 “Untrustworthy Entities” can also apply for “credit restoration” after six months if they can show that they have rectified their untrustworthy behaviors.185 In contrast, sanctions for “Seriously Illegal and Untrustworthy Entities” generally last for three years.186 After one year, these entities must have fulfilled their obligations under administrative penalty decisions, rectified adverse impacts, and avoided receiving additional penalties if they are to be eligible to improve their profiles.187

Regarding error correction, the current system only addresses operational errors in rules enforcement; it does not adjust unreasonable rules in the personalized law system. Currently, the IP Protection Department’s categorization of an entity as “Untrustworthy” must be based on administrative adjudications or similar processes.188 Entities can challenge this decision through administrative review and litigation processes, which offer entities a chance to overturn these decisions, or to have them declared illegal or invalid.189 If the administrative decision is overturned, Article 12 of the Credit Management Regulations allows the affected entity to petition the IP Protection Department to amend its profile.190 Theoretically, though, this correction should be automatic, as the regulations require any department whose decision is reversed to report the reversal to the IP Protection Department within five working days.191 Upon receiving this notification, the IP Protection Department must coordinate with relevant departments, cease public announcements, and remove punitive measures within five working days.192 This process leads to the removal of negative publicity and sanctions typically within ten working days. If the IP Protection Department refuses to amend the profile, then the entity can contest this decision through administrative review and litigation.193

Similarly, an entity labeled as “Seriously Illegal and Untrustworthy” can challenge its profile via administrative review or litigation.194 If the administrative penalty that led to the negative profile is overturned or declared illegal, the public announcement of its status and the revocation of sanctions should occur within three working days.195

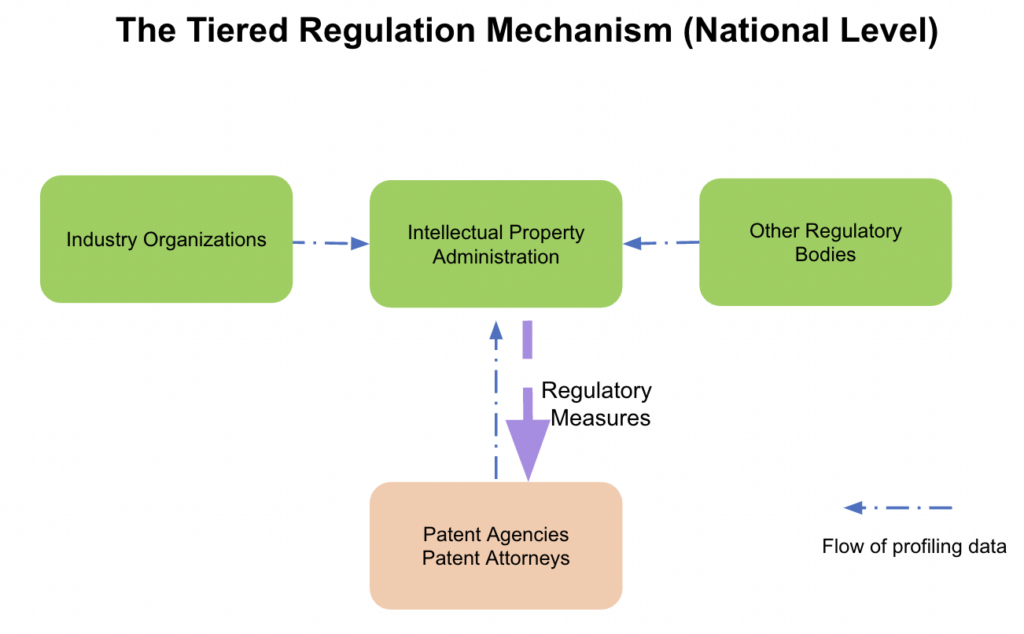

C. The Tiered Regulation Mechanism

The Tiered Regulation Mechanism—another significant aspect of China’s integration of social credit data with patent law—targets patent-related market entities. Initiated after the Reward and Punishment Mechanism, the Tiered Regulation Mechanism currently regulates patent agencies and patent attorneys at the national level.196 The broader regulation of other market entities remains experimental in various regions across the country.197 This section focuses on the national aspect of the mechanism. The Patent Agency Credit Evaluation Management Measures (Trial) (“Credit Evaluation Measures”) effective from May 1, 2023, uses social credit scores to regulate patent agencies and patent attorneys.198 The following diagram helps to illustrate this mechanism’s structure and functionality.

Figure 2 illustrates the structure and key components of the Tiered Regulation Mechanism at the national level. The Patent Agency Management System, created and operated by the National Intellectual Property Administration, serves as the central hub for collecting and integrating diverse data sources, including administrative and regulatory information from national and local intellectual property departments, input from patent agency industry organizations, data from other industry regulatory bodies and industry organizations, and self-reported data from the patent agencies and attorneys themselves.199 Using this data, the Patent Agency Management System categorizes entities into one of five tiers based on their accrued credit points. The credit points are determined by the Credit Evaluation Indicators System and Evaluation Rules for Patent Attorneys and the Credit Evaluation Indicators System and Evaluation Rules for Patent Agencies. Based on their tier, patent agencies and attorneys are subject to corresponding regulatory measures, ranging from rewards and preferential treatment for those in the higher tiers to increased scrutiny and restrictions for those in the lower tiers.

1. Profiling Rules

Prior to the Tiered Regulation Mechanism’s inception, the regulation of patent agencies and attorneys already occurred under existing patent laws.200 This earlier form of regulation facilitated the establishment of each entity’s initial profile. Specifically, before providing patent-related services, patent agencies were required to secure approval from the State Council’s patent administration department,201 whereas attorneys had to pass a qualification exam and register with provincial patent departments.202 These procedures enabled the documentation of the basic information of these entities, which could then be used for profiling.

The Tiered Regulation Mechanism builds on this foundation by imposing an informational component that evaluates and scores these entities based on the relevant data gathered by the Patent Agency Management System.203 Specifically, the system transforms this pre-existing mechanism for documentation into a dynamic scoring framework. According to the Credit Evaluation Measures, the Patent Agency Management System categorizes the entities into one of five tiers based on their accrued credit points.204 These tiers are “A+” (over 100 credit points), “A” (90 to 100 credit points), “B” (80 to 89 credit points), “C” (60 to 79 credit points), and “D” (below 60 credit points).205 The initial base score for each entity is 100 points, which the system grants automatically.206 Subsequent data added to the system can increase scores and potentially upgrade them or can lead to score reduction and potential downgrades.207

The process of adding or deducting points simplifies multi-dimensional matters (such as various behaviors, punishments, and honors) into a single measurement standard: the score. The basis for scoring the entities currently follows the Credit Evaluation Indicators System and Evaluation Rules for Patent Attorneys and the Credit Evaluation Indicators System and Evaluation Rules for Patent Agencies.208 Both sets of rules set out similar scoring schemes. Positive data typically adds 1 to 3 points to a patent attorney’s score.209 This can include records of provincial or higher-level government accolades, serving as industry integrity volunteers, providing information about others’ misconduct, etc.210 The criteria for awarding points to patent agencies largely overlap with those for attorneys. Agencies also earn points for awards, volunteer work, and providing information about misconduct by others.211

Conversely, data relating to negative matters lowers the score. Eighteen items, categorized into three groups—“unprofessional behavior,” “penalty,” and “sanctions by industry association”—can lead to deductions for patent attorneys.212 The most significant deductions, amounting to 100 points, are imposed for criminal penalties related to patent agency violations and revocation of the patent attorney’s license.213 The smallest deduction, 15 points, results from a warning from the industry association.214 Other items leading to deductions include refusing to execute administrative penalty decisions (a 20-point deduction), receiving a warning as an administrative penalty (30 points), engaging in speculative patent applications (40 points), or being part of an agency whose license is revoked (60 points).215

Likewise, patent agencies are subject to 25 deduction items, arranged into categories of “unprofessional management,” “operational anomalies,” “penalties,” and “sanctions by industry associations.”216 Deductions range from 10 to 100 points, with the highest penalties imposed for criminal violations or license revocation affecting agencies or their senior executives.217 The lowest deduction (10 points) applies to administrative issues like delayed annual reporting.218 Other penalties fall between 15 to 60 points for various operational anomalies.219

2. Personalized Rules

The government applies personalized rules to the patent agencies and patent attorneys based on their credit tier, which ranges from “A+” to “D.” For entities rated “A+” and “A,” the Credit Evaluation Measures provide a series of preferential treatments to reward their good standing.220 These privileges include fewer routine inspections, streamlined administrative approval processes, and prioritization in applications and reviews for fiscal fund projects.221 Entities rated “B” receive relatively neutral measures under the Credit Evaluation Measures.222 This indicates that these patent agencies and attorneys face standard business supervision and receive necessary business guidance when required.223

In contrast, the system subjects entities with “C” and “D” ratings to more stringent, even punitive, governance strategies. “C” entities receive heightened scrutiny, including increased inspection frequency, targeted business guidance, and policy education.224 This category of entities undergoes a rigorous review process for applications involving fiscal funds and formal records of facilitation measures, such as expedited patent examination requests.226 Designated as primary targets for regulatory oversight, these entities face frequent inspections, strict legal supervision, and limitations on the use of administrative facilitation measures like the notification commitment system.227 Moreover, their access to preferential policies, fiscal fund projects, facilitation measure records, and participation in various intellectual property activities, including evaluations, awards, and expert recommendations is significantly curtailed.228

3. Communication Rules

The communication of the personalized rules of the Tiered Regulation Mechanism echoes the approach of the Reward and Punishment Mechanism.229 This involves the transmission of a complete set of rules to the regulated entities.230 The authorities predetermine and officially declare the rules to the public through the Credit Evaluation Measures.231 This document gives patent agencies and attorneys the opportunity to comprehend thoroughly the entire spectrum of personalized rules that it describes.

Also like the Reward and Punishment Mechanism, there is no immediate temporal connection between the communication of rules and the subsequent actions of the entities, such as engaging in volunteer activities or ceasing to submit speculative patent applications. But unlike the Reward and Punishment Mechanism, where an entity in the “Entities with Good Credit for Three Consecutive Years” category can only infer its profile, the entities in the Tiered Regulation Mechanism can figure out their profiles through the Patent Agency Management System.232 Determining their tiers lets entities know which personalized rules they must follow. The Patent Agency Management System gives patent agencies and attorneys access to detailed information regarding their credit scoring.233 Patent agencies can view their profiles, detailed scoring, and the profiles of patent attorneys associated with their organizations, while individual patent attorneys can read their personal profiles and scoring details.234

The public can also see the profiles of patent agencies and attorneys through the system, although scoring details remain confidential.235 The public accessibility of these profiles creates a deterrent effect through public shaming of entities with negative profiles, affecting their reputational standing and commercial relations.236 Simultaneously, it empowers clients and potential partners by giving them crucial information, which enables them to make informed decisions about which patent agencies and attorneys to work with.

4. Adjustment Rules

Both Mechanisms structure their adjustment rules to include both duration and error correction components. A distinct feature of the Tiered Regulation Mechanism is its emphasis on the time-bound effect of collected data on an entity’s profile rather than on the regulatory measures.237 Specifically, both positive and negative data affect an entity’s profile for a duration of twelve months. After this period, the influence of this data is nullified; the data is effectively reset and no longer factors into the entity’s credit score.238

Furthermore, the Tiered Regulation Mechanism incorporates a credit restoration process, which allows entities to recover from past misconduct.239 Six months after the successful rectification and the fulfillment of the relevant obligations, entities may apply for credit restoration.240 This process requires them to submit evidence of corrective actions and fulfilled obligations for review.241 Approved applications result in the restoration of deducted credit points, facilitating an improvement in the entity’s credit tier.242 However, conditions apply to this process, such as the barring of entities that have already restored credit in the previous twelve months, that submit fraudulent applications, or that are prohibited from restoration due to legal or policy constraints.243 This mirrors the duration regulations of the Reward and Punishment Mechanism, underscoring the compliance encouragement objective inherent in the social credit system.

Error correction in the Tiered Regulation Mechanism focuses on addressing the application of rules rather than on adjusting the rules themselves, mirroring the approach of the Reward and Punishment Mechanism. Article 10 of the Credit Evaluation Measures allows patent agencies and attorneys to challenge their credit scores or profiles.244 They can submit their objections, with supporting evidence, through the Patent Agency Management System, for verification by the relevant patent management departments.245 By law, these departments must complete the verification within fifteen working days and communicate the outcomes to the applicants.246 If they validate the objections, then they adjust the entity’s credit score and tier accordingly.247

D. Assessment of the Two Mechanisms

1. Profiling Rules

In the Reward and Punishment Mechanism, the scope of data collection is relatively narrow, focusing primarily on the compliance records that governmental entities generate. This limited range of data, while possibly restricting the granularity of entity profiles, has its advantages. It reduces the costs of data collection, as these records are produced and gathered during routine administrative operations, and it guarantees the authenticity of the data, which stems from formal administrative decisions.248 In contrast, the Tiered Regulation Mechanism adopts a more expansive data collection approach, incorporating a wider array of data from administrative, industrial, and self-reported sources.249 This comprehensive method, although more elaborate, introduces the challenges of ensuring the trustworthiness of data, especially the self-reported information from regulated entities. Such data necessitates stringent verification processes to confirm its authenticity and to manage the risk of misinformation effectively.

2. Personalized Rules

The personalized rules of both the Reward and Punishment Mechanism and the Tiered Regulation Mechanism mark an advancement of the rules in China’s patent system towards precise regulation by tailoring legal rules based on the nuances of individual entities.250 The targeted approach of the Reward and Punishment Mechanism enhances the disincentives to infringers and entities that engage in speculative patent filings, while it improves the incentives to entities exhibiting consistent compliance. The differential treatment of the Tiered Regulation Mechanism makes the incentives more targeted and boosts the efficiency of resource allocation among administrative authorities, as it ensures that compliant entities are not over-regulated while focusing on managing frequent violators. By shifting from uniform, one-size-fits-all rules to a more nuanced, data-driven approach, these mechanisms counteract both the over-inclusiveness and the under-inclusiveness of the conventional patent system.

However, the personalized rules of both mechanisms are not without their limitations. First, due to their nature as crude personalization models, the legal content remains relatively static, which limits the system’s ability to respond dynamically to real-time changes in entities’ behaviors or circumstances, potentially reducing its effectiveness. Second, both the Reward and Punishment Mechanism and the Tiered Regulation Mechanism have a transparency issue. The specific reasoning behind punitive measures, rewards, preferential treatments, or stricter treatments remains undisclosed, leading to a lack of clarity that can hinder stakeholders’ comprehension and challenge the legitimacy of these regulatory frameworks.251 Third, they raise concerns regarding the proportionality and appropriateness of the measures.252 For instance, the Reward and Punishment Mechanism enacts up to 38 joint punitive actions across various governmental departments for “Seriously Illegal and Untrustworthy Entities,” which can lead to excessively harsh sanctions that potentially stifle their operations and exceed the mechanism’s deterrent intent. Similarly, the rewards for “Entities with Good Credit for Three Consecutive Years” are predominantly offered by departments dealing with intellectual property, suggesting a narrow scope of incentives that might not sufficiently motivate entities toward higher compliance levels.

3. Communication Rules

To disseminate information to regulated entities, the Reward and Punishment Mechanism and the Tiered Regulation Mechanism adopt an approach that resembles conventional laws. By publicly disclosing both the full contents of the personalized rules and the outcomes of profiling, these mechanisms ensure that all regulated entities are thoroughly informed about the regulatory framework in which they operate. It is generally beneficial to inform regulated entities about the content of law, as the knowledge of law is inherently valuable and essential for ensuring accountability.253 Crucially, this method of conveying rules upholds the “value of shared experience in interpreting and following laws.”254 The collective understanding and application of these rules fosters a sense of communal participation in the legal process that mitigates the risk of alienation or fragmentation within the community. Moreover, public shaming, an outcome of disclosing the profiles of regulated entities, serves as a potent deterrent against non-compliance—creating another mechanism from which entities can be fully informed of the regulatory framework and relevant dropdown effects, such as the effect of associating with the named entity.255 This public awareness strategy allows the general population to avoid interactions with unreliable entities, as non-compliance is indicative of irresponsibility.

However, the mechanisms’ communication strategies also have shortcomings. The informational gaps inherent in the disclosed rules represent a significant concern. For instance, the Reward and Punishment Mechanism does not explicitly guarantee the benefits that “Entities with Good Credit for Three Consecutive Years” stand to gain,256 which can lead to inconsistent application. Similarly, phrases in the personalized rules section of the Tiered Regulation Mechanism like “may reduce,” “relevant administrative approvals,” “providing business guidance when appropriate,” and “implement corresponding incentives and tiered regulatory measures”257 leave room for discretion, introducing uncertainty for regulated entities. In addition, the fact that the authorities neither communicate nor explicitly acknowledge the positive profiles of “Entities with Good Credit for Three Consecutive Years,” might undermine an entity’s motivation to attain and maintain this status. These challenges underscore the need for more direct communication of the profiles, and for providing personalized rules in a clearer manner.

4. Adjustment Rules

The adjustment rules of both mechanisms are critical for fostering a balanced regulatory environment that allows for rehabilitation and redress. Notably, the duration regulations prevent indefinite sanctions. Allowing credit restoration is instrumental in ensuring that entities are not perennially tarnished by their past misdeeds, and to encourage them to reform promptly. The error correction protocols that give entities the right to challenge inaccuracies in the implementation of rules ensure alignment with the principles of due process and fairness.258 By facilitating administrative review and litigation, the mechanisms empower entities to seek to correct their profiles, letting them safeguard themselves against the unwarranted harm that punitive measures and stricter regulation can cause.

However, these adjustment rules have notable limitations. They focus primarily on addressing operational errors in the application of rules and overlook the substance of the rules themselves. This narrow focus might lead to scenarios in which the rules, despite being applied correctly, are inherently unreasonable or overly punitive.

III. Implications

This section, based on the analysis of the Reward and Punishment Mechanism and the Tiered Regulation Mechanism in China’s patent system, discusses two potential implications of personalization of law. The first is institutional: legal personalization may increase administrative bodies’ control of the legal environment. The second is functional: legal personalization could lead to an expansion of the functions of law, raising important questions about the theoretical justifications and normative principles underlying these new roles.

A. The Redistribution and Rebalancing of Powers

Professor Hans Christoph Grigoleit posits that the movement toward personalized law “will bring about major changes to the structure of power distribution in the judicial system,”259 with major implications for legislative, judicial, and procedural dynamics.260 At the legislative level, personalized law introduces complexities and reduces transparency, potentially increasing expert influence and shifting power either to administrative bodies or private actors.261 This raises concerns about diminishing public control and democratic discourse in lawmaking.262 For the judiciary, more specific legislative commands lead to a reduction in decision-making power, as the courts have less leeway in interpretation.263 Additionally, high-degree personalization could lead to decisions based on nontransparent algorithms, potentially dehumanizing the decision-making process and affecting the acceptability of outcomes.264

Grigoleit’s concerns are particularly relevant when examining the Reward and Punishment Mechanism and the Tiered Regulation Mechanism of China’s patent system. Although these mechanisms demonstrate a rudimentary form of personalization, rather than an advanced stage primarily driven by Big Data and algorithmic analysis, they signify a growing tendency toward a more administratively controlled legal environment. Notably, it is administrative bodies that formulate these personalization mechanisms in the patent system, not the national legislative authorities—the National People’s Congress and its Standing Committee. Cheung and Chen note that this pattern is not confined to the realm of patent law. They observe the establishment of various standards in the SCS without formal legislative procedures.265 Although there is no overt reduction in judicial discretion, it is predominantly administrative agencies, rather than the courts, that enforce these personalization mechanisms. Additionally, the lack of transparency regarding the underlying rationale obscures these mechanisms from public scrutiny, limiting the public’s capacity to influence or challenge these laws and their implementations through legislative and judicial avenues.

This paper posits that as the administrative bodies’ role in shaping and executing personalized law expands, a rebalancing of state powers is imperative in order to prevent abuses and the risk of the infringement of individual rights. In China, legislative and judicial oversight of the administrative agencies’ creation of such personalized laws is generally confined to the setting of broad guidelines and principles, while detailed monitoring of administrative regulations is outside the direct scope of the National People’s Congress and its Standing Committee. The Legislation Law delegates this oversight to the State Council, an administrative entity.266 Specifically, Article 109 of the Legislation Law requires the administrative bodies that make departmental regulations to file their regulations with the State Council, an administrative body, rather than submitting them for legislative review.267 On the judicial front, the scope of review of administrative actions does not typically extend to assessing the constitutionality or legality of the administrative rules themselves.268 Courts focus on the compliance of administrative actions with established laws and regulations, which leaves a gap in oversight, particularly in evaluating the fairness and reasonableness of these administrative regulations.269

One solution to this problem could be to expand the role of the legislative branch. This would involve the creation of a specialized legislative committee, equipped not only with legal experts but also with data scientists and public representatives, responsible for comprehensively reviewing administratively-made personalized laws to ensure that they align with overarching laws and legal principles. As these personalized laws continue to evolve, this committee would engage in periodic audits to identify potential misalignments and unintended consequences.270 Making the outcomes of audits publicly available would enhance transparency and facilitate public trust and acceptance of these laws.

Judicial oversight could be expanded to include a substantive review of the legality and constitutionality of the administrative agencies’ personalized laws. While integrating these reforms into China’s current legal structure presents challenges, as this development could require substantive amendments to the existing legal framework,271 it is a feasible endeavor that addresses the evolving needs of data-driven administrative law. Recognizing the complexities of data-driven legal systems, courts should have access to technical resources, such as data analysis experts to evaluate the rules’ intricacies.272 While making this resource available to courts might not seem urgent in the current stage of crude personalization, it becomes indispensable as the system advances to a more sophisticated stage involving algorithmic personalized law.

Public oversight is also important. In the rudimentary stage of personalized law, transparency in administrative agencies’ rationales vis-a-vis the four categories of rules is paramount to enable public scrutiny.273 Beyond error correction, such public scrutiny fortifies the democratic legitimacy of personalized law.274 The government can bolster this process by incorporating public engagement into the formulation of the system. This could manifest itself through public hearings and open forums for commenting on proposed regulations. These steps would clarify the decision-making process and offer a platform for diverse stakeholder input. As personalized law reaches more advanced stages, disclosure and public participation will continue to be pivotal.275 However, the focus on disclosure and scrutiny would shift toward the design of the algorithms and the data that the administrative agencies and their algorithms consider. Given the increasing complexity of algorithmic systems and the potential for opacity in their decision-making processes, ensuring meaningful public participation and oversight may become increasingly challenging. To address this, governments and administrative agencies will need to develop and implement strategies for explaining the functioning of these algorithmic systems in an accessible manner, such as the use of simplified models, visualizations, or case studies that illustrate how the algorithms operate and make decisions. Additionally, there may be a need for independent audits and assessments of these systems to ensure their fairness, accountability, and adherence to legal and ethical standards. While providing tailored introductions and explanations to the public is important, it is equally crucial to recognize and proactively address the inherent difficulties in achieving full transparency and understanding of complex algorithmic systems.

B. The Expansion of the Function of Law

The data-driven personalization of laws invites a critical examination of the expanding function of legal systems. Consider, for example, the nuanced personalization of traffic laws.276 This approach factors in a driver’s risk level, incorporating data ranging from driving experience and current fatigue to credit scores.277 While using credit scores in traffic law personalization might enhance road safety by assigning more accurate speed limits—a primary goal of traffic regulation—it might also inadvertently influence drivers’ financial behavior. Drivers motivated to attain higher speed limits might engage in timely loan repayments and maintain minimal debt. The use of credit scores to personalized speed limits extends traffic regulation’s function beyond road safety to influencing financial conduct.

Similarly, the expanded functionality of law is evident in the personalization of China’s patent law. The Reward and Punishment Mechanism and the Tiered Regulation Mechanism in China’s patent framework go beyond the traditional focus on innovation promotion to reflect broader policy objectives, including social and ethical considerations. The legal texts of these two mechanisms include the goals of “fostering a fair and honest market and social environment,”278 “promoting self-discipline and honesty,”279 and “strengthening industry self-discipline.”280 Such a blend of objectives demonstrates how the integration of diverse data sets, in this case social credit data largely based on compliance records,281 into the patent law framework contributes to the expansion of its function.

The structure of these mechanisms also reflects this expansion. For example, the Reward and Punishment Mechanism confers advantages, such as priority in patent examination, to entities with a “Good Credit for Three Consecutive Years” status. Priority patent examination and approval could lead to earlier patent grant and, consequently, earlier enforcement rights. In many jurisdictions, including China, while a patent application is pending, the applicant may have provisional rights to monetary compensation.282 However, full enforcement rights are only available once the patent is granted. Although patent protection terms are primarily intended to encourage innovation, giving an entity with good compliance records the opportunity for expedited patent grant and enforcement also encourages compliant behavior across a broad spectrum.

The expansion of the function of law in data-driven personalization introduces two significant challenges. The first is the issue of theoretical justification. Traditional patent law rests on the incentive theory and the disclosure theory, which encourage innovation and the sharing of knowledge.283 However, when this temporal protection is extended to promote compliance behaviors, it introduces a new dimension that established theoretical frameworks do not currently support. This discrepancy is particularly evident as the text of the fundamental legal document of China’s patent system—the Patent Law—does not list the objectives of fostering fair markets and promoting self-discipline in the personalized patent mechanisms. Instead, the Patent Law still emphasizes the traditional goals of promoting innovation and sharing and implementing knowledge.284

Second, there is a complexity in the cumulative effects of nudges across multiple legal domains. For example, in the case of Ben-Shahar and Porat’s personalized traffic laws, if a credit score is used to personalize laws across various domains, then the use of such data nudges a person’s financial behavior across each of those domains, rather than individualizing the behavior to each instance or legal domain. This integration of data for law personalization could lead to intricate patterns within the legal system, potentially leading to “unintended consequences.”285 The criticisms of China’s application of social credit data in law personalization highlight these concerns, as multiple legal areas combine to produce disproportionate penalties,286 exemplifying the pitfalls of expanded functions and cumulative nudge effects.

In response to these challenges, scholars and policymakers must undertake two pivotal tasks. First, they must work toward creating intricate and comprehensive normative frameworks that can evaluate the law’s expanded functions, integrating its traditional objectives with the new considerations that arise from incorporating diverse data sets.287 This updated normative theory should guide rule generation and enhance the public understanding of the rationale behind personalized laws. Second, and perhaps more challenging, is the development of precise descriptive models to analyze and assess the cumulative effects of nudges. These models would help to identify unintended consequences and find interventions to mitigate them, perhaps by calibrating the combined effects of multiple personalized legal domains. Overall, the personalization of law offers the opportunity to shape legal systems that are technologically advanced and contextually relevant while also presenting the challenge of ensuring that this new legal form remains ethically grounded and operationally sound.

Conclusion

The analysis of the Reward and Punishment Mechanism and the Tiered Regulation Mechanism in China’s patent law framework demonstrates the significant impact of integrating social credit data into legal systems. These mechanisms represent a shift towards personalized law, marking a departure from traditional, uniform legal frameworks and moving towards a more nuanced, data-driven approach to regulation.

The Reward and Punishment Mechanism, which categorizes entities into “Untrustworthy Entities,” “Seriously Illegal and Untrustworthy Entities,” and “Entities with Good Credit for Three Consecutive Years,” applies corresponding incentives or sanctions based on these profiles. This targeted approach enhances disincentives for infringers and entities engaging in speculative patent filings while improving incentives for consistently compliant entities. Similarly, the Tiered Regulation Mechanism assigns patent agencies and attorneys to one of five tiers based on their social credit scores, subjecting them to differentiated regulatory measures. This approach optimizes resource allocation among administrative authorities, ensuring compliant entities are not over-regulated while focusing on managing frequent violators.

The evaluation of these mechanisms highlights the potential of personalized law to address the limitations of one-size-fits-all legal frameworks. However, it also reveals challenges, such as the lack of transparency in the reasoning behind punitive measures and rewards, concerns about the proportionality of sanctions, and the need for more direct communication of profiles and personalized rules.

The implications of this shift are profound. Institutionally, the growing prominence of administrative agencies in the enforcement of personalized laws signals a reconfiguration of power dynamics within the legal system. This development necessitates a reassessment of the roles and responsibilities of both legislative and judicial bodies in order to ensure a balanced distribution of state powers and to protect individuals’ rights within this new legal landscape. Functionally, the expansion of the patent law’s function, from encouraging innovation to fostering a compliant and disciplined market environment, challenges the traditional theoretical basis of patent law. This expanded scope calls for a comprehensive theoretical reevaluation to ensure that the laws are not only effective in their new roles but also remain grounded in normative principles and avoid unintended consequences.

In addition to the broader implications for legal systems and governance, this paper’s analysis offers critical insights for innovative enterprises, both domestic and foreign, operating within the Chinese market. The integration of social credit data into China’s patent law provides a unique regulatory environment that they must navigate. For transnational businesses, adapting to this data-driven legal landscape means reevaluating their operational and compliance strategies to align with the nuanced requirements and opportunities presented by China’s evolving patent system. Moreover, the insights gleaned from China’s experience can serve as a valuable lesson for transnational companies as they prepare for the potential adoption of similar data-driven legal frameworks in other jurisdictions.

Some describe personalized law as “incredibly timely, even visionary” and believe that it will “dramatically change the law.”288 China’s patent law, personalized through social credit data, exemplifies the development of legal systems in the digital age. It underscores the need for scholars, policymakers, and legal practitioners to navigate the challenges and harness the opportunities that data-driven law presents. The resulting dialogue will be crucial, not only for China, but also for the global legal community.

Appendix

Table 1

| Credit Evaluation Indicators System and Evaluation Rules for Patent Attorneys (Simplified Version) | |

|---|---|

| Base Score (100 points) | |

| Positive Information (10 additional points maximum) |

|

| Negative Information (points reduction) |

|