Despite the two lawsuits recently brought against MSCHF, the brand isn’t too worried about being sued. The art collective aptly pronounced “Mischief” approaches lawsuits as it does everything, from its creations to its speaking engagement at the Engelberg Center on Innovation Law & Policy’s Fake Symposium—as a gimmick. However, there is nothing gimmicky about the current lawsuit against MSCHF pending in the Second Circuit, which could clarify the ever-blurry distinction between expressive and commercial works in trademark law. Before discussing that lawsuit, it’s necessary to learn what MSCHF’s all about.

To that end, the Engelberg Center on Innovation Law & Policy invited John Belcaster, MSCHF’s general counsel, to speak at its Fake Symposium on September 23, 2022, in a fireside chat with NYU School of Law vice dean and professor Jeanne Fromer and Megan Bannigan, a Debevoise & Plimpton partner representing MSCHF. But, instead of providing explanatory information about the company and its legal defenses, MSCHF pulled one over on the audience. Three individuals sat on the stage, each introducing themselves as “John Belcaster, general counsel of MSCHF” and piping in throughout the chat with their “legal” opinions. At the end of the event, they polled the audience to see who everyone thought was the real Belcaster. Yet the gimmick continued through the reveal—my internet sleuthing uncovered that the man who claimed to be the real Belcaster at the end was, in fact, not. He and the other fake Belcaster were non-legal employees of MSCHF.

During the fireside chat, Bannigan told the audience: “One of the fundamental foundation questions you have to ask yourself is who is MSCHF and why are they doing what they’re doing?” While sometimes the answer to that is hard to pin down, often it is that they are making creations to poke fun at, riff on, or comment on something put out by another party or a societal or industry practice. MSCHF releases new creations every two weeks in exclusive drops. These drops push boundaries and play with the law, often intentionally. While the First Amendment protects artistic expression, American law attempts to strike a balance between that protection and trademark law’s commercial and consumer protections by distinguishing between expressive and commercial works. The fuzzy line between such works is one that MSCHF frequently straddles.

Many of MSCHF’s boundary-pushing drops have not spurred any legal action. One notorious example is the Jesus Shoes, altered Nike Air Max 97s containing drops of holy water from the Jordan River in the soles, priced at $1,000 per pair. Gabriel Whaley, MSCHF’s chief executive, told the New York Times that the shoes were a form of social commentary, making fun of collab culture. Despite having no affiliation with or permission from Nike, MSCHF left the trademarked swoosh visible on the shoe. Nike didn’t publicly disavow the shoe or bring any legal action against MSCHF—much to the disappointment of Kevin Wiesner, a creative director at MSCHF who told the Times: “That would’ve been rad.” It’s likely Nike didn’t sue for trademark infringement because the sneaker garnered minimal negative press and consumer confusion.

Another example is the Severed Spots drop, in which MSCHF cut up a Damien Hirst spot painting and sold each spot for $480 apiece. The claimed purpose was to criticize the practice of investors pooling resources to buy art, each gaining fractionalized ownership and then flipping the work. Hirst never acknowledged the drop or brought any legal claim, but arguably, he could have.

With its Cease & Desist Grand Prix drop, MSCHF admittedly and intentionally crossed legal boundaries. The company sold shirts that illegally had the logos of eight major companies on them (think Disney, Coca-Cola, Microsoft, etc.). MSCHF promised shoppers that if they bought the shirt with the logo of the first company to end up sending them a cease and desist letter, they would win a free, exclusive hat. MSCHF co-founder Daniel Greenberg told Women’s Wear Daily, “We chose companies that are large enough to be worth infringing on and are mostly known for being litigious….The C&D letter [is] essentially a unilateral censorship tool. With C&D Grand Prix, we can bait this predictable and lamentable response and make it part of our own work, inverting the power dynamic.” At the Fake Symposium, one of the MSCHF employees (not the real Belcaster) revealed that the gimmick didn’t spur much legal action, with only Subway sending a cease and desist.

Then, there are the drops that led to lawsuits. In the past year and a half, two major shoe retailers have sued MSCHF. Yet, the brand welcomes the litigation, viewing it as it views any other press: as marketing and good publicity. On The Complex Sneakers Podcast, MSCHF’s chief creative director, Lukas Bentel, was asked, “How hyped do you guys get when you guys get sued?” “It means we’re doing something good, I think,” he responded. “We’re not really worried about it too much.” At the Fake Symposium, one of the MSCHF employees (again, not the real Belcaster) said MSCHF doesn’t do what they do to get sued, “the suing is mostly just a marketing gimmick.” While MSCHF views litigation as marketing and publicity for the brand, such legal action has much broader implications, particularly for the trademark law community.

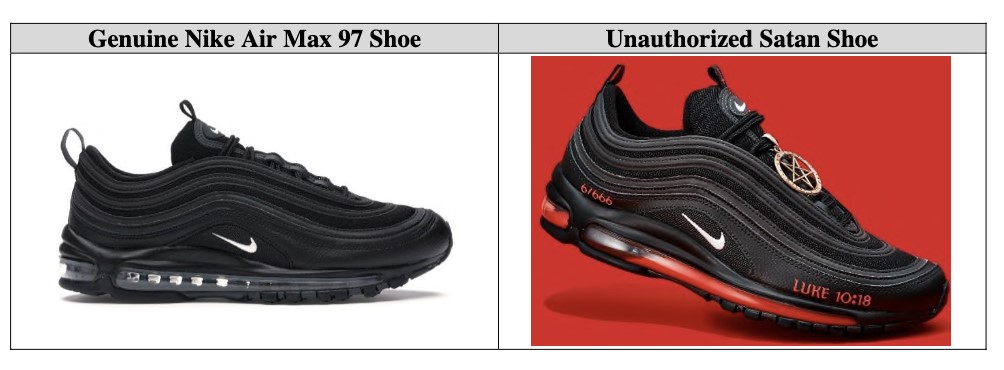

Nike brought suit against MSCHF in March 2021 regarding the Satan Shoes, created in collaboration with musician Lil Nas X. The sneakers were Nike Air Max 97s adorned with an upside-down cross, bronze pentagram, and a single drop of human blood (from MSCHF employees) in the soles, priced at $1,018 per pair. As with the Jesus Shoes, Nike’s trademarked swoosh was visible on the sneakers. Unlike the Jesus Shoes, the Satan Shoes quickly garnered widespread negative press and perception. Nike promptly disavowed the product and filed a complaint for trademark infringement and dilution, as well as unfair competition. MSCHF managed to leverage the legal action as another opportunity for commentary and commerce: dropping a Legal Fees t-shirt displaying the first page of Nike’s legal complaint with drawn-on devil horns. In the end, Nike won a temporary restraining order in district court, and then the case settled quickly thereafter. Artists and trademark lawyers alike were left with many unanswered questions. Some people believed MSCHF had key defenses at its disposal, such as the first sale doctrine and fair use. Others predicted the case would bring about MSCHF’s demise. It is still unknown whether MSCHF’s claim of using the Nike Air Max 97 as a canvas for its artistic creation is a potentially successful legal defense.

Just a year later, MSCHF was back in court facing a lawsuit brought by Vans in April 2022. The suit concerns the Wavy Baby, a sneaker created by taking a photograph of the Vans’ Old Skool shoe, including the trademarked side stripe, and putting it through a digital filter that liquified it to create a wavy-soled shoe. According to a statement put out by MSCHF, the sneakers are a parody, critiquing sneaker companies’ practice of riffing off each other by taking an object “that is itself a symbol” and completely distorting it. On The Complex Sneakers Podcast, Bentel said, “Yes, the base of the shoe before the transformation is, of course, a Vans, no doubting that. We are completely playing into that space, but it is a really unique transformation that Vans would not ever have done.” Vans filed claims of trademark infringement and dilution, along with unfair competition under both federal and New York state law. The district court granted Vans a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction, finding the Wavy Baby shoes to be an infringement because they are likely to cause consumer confusion and fail to be a successful parody.

The case, which is currently pending in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, is one that, as Bannigan put it at the Fake Symposium, “everyone in the trademark community is watching.” That is because it provides the Second Circuit with an opportunity to establish some guidelines as to the balance between First Amendment rights and trademark protections over expressive merchandise. The district court did not consider the infamous Rogers test, applied when both an expressive work and trademark are at play. That case stands for the proposition that when a defendant’s product is expressive, the Lanham Act must be interpreted narrowly so as not to conflict with the First Amendment. Now, the lingering questions are whether MSCHF’s sneakers are expressive and, more broadly, what exactly constitutes an expressive work under the Rogers test. This opportunity to clarify what qualifies as expressive as opposed to purely commercial and to delineate the line between the two categories is huge.

Not only will the outcome of the Vans case greatly impact creatives and trademark lawyers, but it could also alter MSCHF’s entire business model. MSCHF currently has plans to launch its own sneaker line, with supposedly none of the styles riffing off or modifying existing shoes. Depending on what the Second Circuit has to say about the Wavy Baby, this line might end up being one of many instances in which MSCHF shies away from playing with the law and commenting on something put out by another company. Only time will tell if MSCHF will continue to use gimmicks and litigation as tools for generating publicity or whether the law will reign them in.