Richard Chused*

Download a PDF of this article here.

Introduction

In the middle of the night on December 17, 1989, Arthur di Modica arranged for the sudden deposit of an eleven- by-sixteen-foot, 7,100-pound bronze sculpture—Charging Bull—in front of the New York Stock Exchange. Di Modica neither notified nor sought permission from the N.Y. Stock Exchange or City of New York before doing so.1 The nocturnal2 event created a major hubbub. Di Modica claimed that the bull was a Christmas present to the city, celebrating “the strength and power of the American people” in recovering from the economic pain of the financial and stock market crashes of 1987.3

Just over twenty-seven years later, another sculpture unexpectedly appeared in downtown New York City. On March 7, 2017—the eve of International Women’s Day—a diminutive, four-foot-tall bronze figure—Fearless Girl—was placed staring down the bull from a short distance away. This also caused consternation and amazement.4 It too was deposited late at night, without permission from either public authorities or private property owners. In the ensuing months, disagreements among artists, local groups, and city authorities led to both works being moved, contests over property and copyright interests, arguments over the propriety of one work “commenting” on another, and threats of litigation. The tale has the makings of a great novel.

Most relevant to this essay, the out-of-the-blue arrival of Fearless Girl led di Modica, creator of Charging Bull, to claim that he enjoyed a right to control the setting in which his work was displayed and the character and quality of artworks that could be placed nearby.5 This essay briefly tracks the history of Charging Bull and Fearless Girl, before investigating the nature of di Modica’s claims and the role of copyright law in resolving the disputes.6 What, if anything, does copyright law have to say about the importance of compositional choices made during the creation and display of a particular work, the compositional relationships between a work and other works placed nearby, and the compositional significance of the physical setting in which a work is displayed?

I. A Tale of Compositional Conflict

A. A Brief History of Charging Bull

The story of Charging Bull and Fearless Girl has been told elsewhere in some detail.7 Only a brief retelling is warranted here. Shortly after the devastating financial crash of October 19, 1987, di Modica began contemplating the Charging Bull project.8 In di Modica’s view, the bull’s obvious reference to the rising stock prices of a bull market symbolized the vibrant and resilient fabric of American culture.

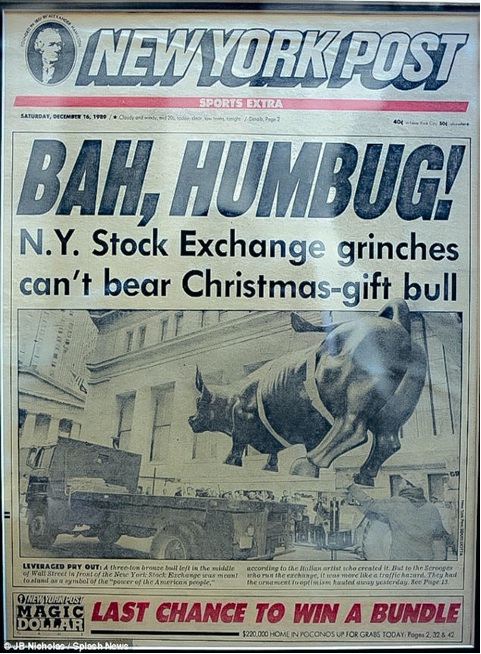

Almost immediately after Charging Bull was deposited in front of the N.Y. Stock Exchange, the trading mart complained to the city and the bull was moved to storage in Queens. The city agreed with the exchange’s complaints that automobile and foot traffic around the work were causing disruptions.9 Cries of public dismay followed. The now renowned front page of the New York Post, pictured below,10 excoriated the N.Y. Stock Exchange for the sculpture’s removal. Public calls for the work’s return to public view led to discussions between di Modica, his spokesperson Arthur Piccolo, who was also chairman of the Bowling Green Association, and Henry Stern, the New York City Parks Commissioner. The parties reached an agreement to retrieve the sculpture from storage and place it at Bowling Green, a small, cobblestone park located just a few blocks from the N.Y. Stock Exchange—but not within its view. Di Modica reportedly felt “fantastic” about the bull’s new location.11 During the bull’s subsequent solo stay at Bowling Green, Charging Bull became a major tourist destination and was viewed by millions.12

After Fearless Girl appeared years later, staring down the bull at Bowling Green,13 police and others once again voiced concerns over automobile congestion and tourists crowding around the two pieces. Fears of accidents, as well as concerns raised by di Modica, who was strongly opposed to the presence of the new work, led to the diminutive child’s removal from Bowling Green. On December 10, 2018, about nine months after Fearless Girl’s first appearance, she was removed and taken a few blocks away to her current location: the front of the N.Y. Stock Exchange.14 The story came full circle. The two pieces swapped locations.

At the time Fearless Girl was relocated, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio claimed that Charging Bull would also be moved back near the N.Y. Stock Exchange, and that it was important to keep the two works together.15 Brian Boucher, on behalf of ArtNet News, reported that di Modica was “steaming mad” at the prospect of the city reuniting the two sculptures.16

[T]he sculpture, by artist Kristen Visbal, was soon unmasked as the brainchild of ad agency McCann New York and investment firm State Street Global Advisors as part of a campaign to land more women on corporate boards. (Spoiler alert: State Street turned out to be not so great when it came to gender or racial equity.)

The arrival of Fearless Girl irked Di Modica, who maintains that the bronze lass turned his own sculpture into part of an ad campaign. He took legal action, retaining none other than civil rights crusader Normal Siegel to represent him. That led in turn to a tweeted criticism by Mayor Bill di Blasio, accusing Di Modica of not liking “women taking up space.” Ultimately, to better accommodate the crowds headed there just to see her, the Girl moved to a spot across from the NYSE. (That means Charging Bull’s relocation would put the beast close, again, to his nemesis.)17

After di Modica objected to his sculpture being relocated back to the N.Y. Stock Exchange in the presence of Fearless Girl, Mayor de Blasio apparently backed down, at least temporarily. De Blasio claimed that the city was still considering moving Charging Bull but that no definite plans had been made. 18 In the fall of 2019, the city withdrew its application from the Public Design Commission to move di Modica’s work back to the N.Y. Stock Exchange, allegedly because it could not decide exactly where to place it. In June 2020, the Commission finally entertained a proposal from the Mayor’s office to move Charging Bull, only to turn it down.19 The local community planning board had previously declined to approve a similar proposal. 20

As of this essay’s writing, the city’s plan to move Charging Bull somewhere near the N.Y. Stock Exchange and Fearless Girl remains embroiled in controversy. 21 The city continues to profess concern about automobile and pedestrian traffic if the two works are placed next to each other at the Exchange. 22 Yet, while di Modica claims that there is an agreement to leave the bull in Bowling Green permanently, the existence of such a deal is disputed. There is no written evidence to support it.23

Fearless Girl is not the only work to challenge di Modica’s claim for control over the environment in which his sculpture is displayed. Both before and after Fearless Girl, various “commentators” have made their own guerilla statements about the bull, asserting positions quite different from di Modica’s view of his work as an optimistic declaration of American resilience. On Christmas Eve in 2010, for example, artist Agata Oleksiak (typically called. “Olek”) wrapped Charging Bull in crocheted pink, purple, and green yarn as an artistic statement, creating a rather less fearsome and softer creature.24 The following year, Occupy Wall Street began its demonstrations by gathering around the bull.25 A poster, displayed below, used the bull’s image to promote the event.26 In 2017, a woman splattered the bull with blue paint as a protest against President Donald J. Trump’s withdrawal of the United States from the Paris Accords, an international agreement on climate change.27 Two years later, another paint splatter incident protesting climate change occurred, this time covering the bull in red to signify “blood on the hands” of the financial community.28

As with many other artworks on public display, Charging Bull’s observers imposed their own points of view on the work. Di Modica could not prevent such reactions. But they typically lasted only a short while before being removed or cleaned up. The single exception occurred in 2019, when a Texas trucker wielding a metal banjo and cursing President Trump whacked the instrument against the bull, inflicting a significant gash on one horn.29 The damage took some time and $15,000 to repair. 30

B. Origins of Fearless Girl and Subsequent Controversy

The most famous of all the commentators on the bull remains the diminutive, four-foot tall Fearless Girl standing akimbo with hands on her hips and staring directly down at the oversized bull charging toward her. Overnight, the Charging Bull and Fearless Girl pieces combined to evoke an array of vigorous statements about the relationships between women and finance, women and men, and the gendered structure of modern society. Fearless Girl appeared to make a forceful case for women to play a more significant role in American society. Or did it?

The sculptor of Fearless Girl was Kristen Visbal, but the project was actually the brainchild of State Street Global Advisors, an international financial management company, and their large, national advertising representative, McMann New York.31 State Street intended to use the sculpture to draw attention to the lack of women in leadership roles across Wall Street and to market its new Gender Diversity Fund. The fund sought investments in firms scoring better than their industry peers on gender diversity.32Fearless Girl, like Charging Bull, was intended to be a short-term display.33 But again, public clamor led to both works being left in place, staring each other down.

There was a major irony to this part of the story: State Street was known to have a spotty record on gender inclusion. 34 As one commentator snarkily noted, “[W]hen de Blasio’s office says he feels it’s important for Fearless Girl to stand up to the bull and ‘what it stands for,’ he’s referring to a fake meaning imposed on the bull by the new statue, and not the artist’s original intent.”35 In short, the notion that Kirsten Visbal placed Fearless Girl at Bowling Green as a guerilla commentary on the bull is misleading at best and fictional at worst. More accurately, it was a brilliant publicity move by a major Wall Street firm with a sketchy gender record.

Fearless

Girl, like Charging Bull, has

also attracted “commentaries” since its arrival in 2017. Perhaps the most

creative was by Alex Gardega. Displeased

that the statue staring down Charging Bull

was merely an advertising stunt by a large investment

firm with few women in leadership positions, Gardega placed Pissing Pug, next to the left leg of the

girl urinating on her foot.36 Manuel Oliver,

whose son Joaquin Oliver was killed in the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School

mass shooting in Parkland, Florida, made another clever and powerful commentary.37

In protest

of gun violence and mass shootings in schools, Oliver placed a bulletproof vest on Fearless Girl, turning her into what others have called Fearful Girl.

38

Finally, on the weekend after

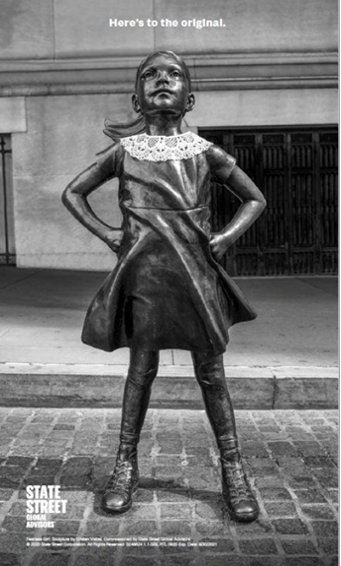

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died, State Street arranged for a “Ginsburg Collar”

to be placed on Fearless Girl, and

displayed the result in a full-page advertisement in the

New York Times to commemorate the justice’s death.39

Left: Alex Gardega next to Fearless Girl and his own Pissing Pug statue.

Right: Manuel Oliver’s statement against school shootings, for which he placed a bulletproof vest on Fearless Girl.

Right: State Street’s advertisement marking Justice Ginsburg’s death, which included the tagline, “Here’s to the original.”

From this very brief telling of the tale, it is clear that the presence of Fearless Girl, whether facing Charging Bull or not, has produced a variety of observations about both itself and the bull. All of these events confirm that even if the creators of public sculptural works retain legal authority over the surrounding environments, they may be sharply limited in their ability to control public commentary about their endeavors.

C. The Legal Issues

From the moment Fearless Girl arrived at Bowling Green, Arturo di Modica expressed deep antagonism about his work being a focus of criticism and social commentary.40 A letter from Norman Siegel and Steven Hyman, di Modica’s attorneys, to Mayor de Blasio just over a month after Fearless Girl appeared made this quite clear.41 Di Modica’s attorneys raised a series of objections to Fearless Girl’s presence near Charging Bull.42 They claimed that leaving Fearless Girl near to Charging Bull violated di Modica’s rights to control reproductions of the bull, to prepare derivative works, and to distribute copies of Charging Bull.43 They also contended that di Modica’s moral right to limit modification of his work was violated.44

For purposes of this essay, two of these claims are notable—the derivative work and moral rights issues. Neither reproductive nor distribution rights were threatened.45 The derivative work question is about the right of an artist to license works that rely on her or his original creation to make a new work.46 The moral rights claim would have to rely on the Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990 (“VARA”). VARA, however, applies only to works created after its effective date.47 Charging Bull was completed and placed at the Stock Exchange the year before the Act went into effect. But the modification terms of VARA are still worth exploring. They, like the provisions on derivative works, raise fascinating questions about the degree to which copyright law allows artists to control the environmental composition in which their works are publicly displayed.

These derivative work and moral rights issues are the primary focus of this essay.48 Usually we think about derivative works as creations adding new original material to a prior work that recasts, transforms, or adapts the original—like a movie made from a novel with the permission of the copyright owner.49 But in this case, Fearless Girl is a far different “creature” than Charging Bull. Its physical and compositional features make no direct use of the bull. It is not wholly analogous to a derivative movie’s use of content in a novel. Nonetheless, its installation nearby clearly commented upon and changed the atmospherics surrounding di Modica’s work. Does that make it a derivative work? Does di Modica have any control over the creation of Fearless Girl or its location?

The moral rights provisions of the copyright code raise closely related issues. The placement of the girl facing the bull created a dramatically new two-sculpture composition. Does only State Street have control over the coupled imagery it created? The modification provisions of the copyright code bar modification of a work of fine art by a party other than the artist that is an “intentional distortion, mutilation, or other modification of that work which would be prejudicial to . . . [the artist’s] honor or reputation.”50 As with the derivative work issue, Fearless Girl did not directly make any physical modifications to Charging Bull. If a change was made by the presence of the girl, it was in the alteration of the bull’s compositional impact. Does such a compositional change constitute a “modification” or “mutilation” within the meaning of VARA? If so, did it endanger di Modica’s honor or reputation?

Before directly approaching these copyright questions, it is important to have at least a basic understanding of various forms of artistic composition. That is taken up in the next section. Following that, I will explore more directly the ways some forms of composition were altered by Fearless Girl and consider the intellectual property consequences of those changes.

II. Charging Bull and Composition

A. A Brief Journey into the Aesthetics of Composition

Sensitivity about both the composition of a work and its relationship to the environment in which it is displayed have been persistent themes in the history of Western art. Attentiveness to these issues touches the heart of artistic creativity. Theorizing a bit about the composition of two-dimensional works provides a baseline for thinking about the ways location and environment may have significant impacts on viewer reactions to any work of art. Models about composition of two-dimensional works have evolved in at least two directions. The first attempts to find scientific and rational notions to explain why many people react more favorably to the appearance of one work than to another. The second views composition as an ineffable, aesthetic, and instinctual judgment.

Some artists use well-known rational or mathematical concepts like the “golden triangle,” the “golden ratio,” or the “rule of three” to construct basic features of their work.51 The first divides a surface into four triangles, with the four edges of the canvas or other material forming the bases of each. The golden ratio is based on the Fibonacci Ratio, a set of points on a surface that creates an elaborate spiral form. The rule of three is the simplest. Simply draw a “tic-tac-toe” grid on the working surface. This standard suggests placing important parts of an image at the points where the tic-tac-toe lines intersect. Some cameras are actually made with a tic-tac-toe grid that can assist a photographer in using the “rule of three.”52 Other conceptual and minimalist artists, such as Sol LeWitt, clearly use mathematical norms to guide their work.53

Not surprisingly, these and other logic systems have been subject to criticism, especially when applied to non-geometric compositions. The dissenters suggest that formulas may work in some cases, but that their fit with human artistic preferences in other settings is loose at best.54 Regardless of the validity of the various “golden” claims, many modern artists find it very difficult to express why or how they decide on the overall composition of works they create. For them, composition is a notion beyond the capacity of logical thinking to describe or define. This view is more appropriate for discussion of the relationships between Charging Bull and Fearless Girl. It is hard to imagine that State Street thought about the girl’s compositional relationship to the bull with mathematical precision. They certainly planned the positioning of the girl so that it stared directly at the bull. But the rest of their spatial interaction—the main subject of this essay—is very difficult to analyze precisely. Such ambiguity in compositional theory signals that grappling with the legal relationships between Charging Bull and Fearless Girl is likely to be as open-ended and conflictual as art itself.

This open-endedness is confirmed by a lucid depiction of subjective sensibility about composition. It may be found in Portraits—a perceptive book written by Michael Kimmelman, a sensitive, sophisticated, and knowledgeable art and architecture critic for The New York Times. 55 Some years ago, Kimmelman invited a number of well-known artists to meet him at museums of their choosing and view works that they believed influenced their artistic development or that they simply liked. His experiences are described in Portraits. During his visit with Jacob Lawrence at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Kimmelman asked Lawrence why he found Sassetta’s56 painting The Journey of the Magi, shown below,57magical. Lawrence responded:

It’s simplified but very complex at the same time. We say “simplicity” and imply something’s easy to accomplish but this isn’t easy. It’s a highly refined composition, and I could describe why formally: the way the shapes balance one another, the way the image moves from dark to light. But there’s something that I can’t describe formally, which is a certain feeling, an intuitiveness, maybe. An emotional authenticity. I’m just projecting here, but I think it seems authentic to me because maybe the artist wasn’t tied up too much in rhetoric, you know, talk, school talk, pedantics [sic]. When I was young I hung around painters and people in the arts, music, theater. I was just beginning to grasp what a theater person or artist meant when he talked about space or rhythm or movement. I couldn’t talk the way they did. At the time I had a more intuitive sense of why I like something, and I still think that’s the most important thing to have.58

Despite the uncertainty about our “knowledge” of the ways artists conceive of compositional forms or the reasons why people react to them in various ways, the overall appearance of a work of art is central to the relationships between artist and viewer. This has been true for centuries. Artists creating early religious paintings and iconography cared deeply about composition. The creation of triptychs is a perfect example. Their three-panel structure had deep resonance with Christian theology and therefore with the compositional choices made by artists in the panels themselves. The “architecture” of the style led naturally to the need to create relationships between the three segments of such works. But triptychs also were frequently placed in particular locations in churches.59Their environmental placement often was an important part in the artistic design of the triptychs themselves.

Artists have also experimented with ways to supplement traditional forms of religious painting with certain more elaborate “additions” for quite some time. Often these were designed to draw a viewer’s eyes to a particular figure in the composition or a phrase in a book. Artists of sacred art, for example, began to use gold leaf and other appliques to enhance their works. Similarly, an array of early book writers employed highly decorative calligraphy and images on some of their pages.60 These flourishes also were critical aspects of composition. They accentuated reverence, authority, power, holy figures, or important religious concepts. Golden halos around the heads of important Christian figures, of course, were commonplace in medieval art.61 The Western artists of these early works combined different artistic techniques, added new elements to their compositions, and crafted a variety of ways to contrast, compare, and emphasize emotional, religious, narrative, and compositional aspects of their work.

Some of these early innovations were precursors to much twentieth century art. The use of figurative subject matter and landscapes gradually gave way to increasingly secular and abstract compositions. Painters were heavily influenced by the relationships of triptych panels and by the addition of “artificial” methods (such as the use of gold leaf) to emphasize characters or features in works of art. Later artists, like Doménikos Theotokópoulos (“El Greco”) in the sixteenth century, Diego Velázquez in the seventeenth century, and Francisco Goya around the turn of the nineteenth century, each enhanced Western art in distinct ways—abstraction in the case of El Greco, realism and visible emotion in the case of Velazquez, and pathos together with use of lighting effects in the case of Goya.

As depictions of non-religious figures, objects, and scenes blossomed, artists’ use of inanimate features as the central compositional feature of two-dimensional work—animals, home interiors, or still life arrangements—became plausible. By the turn of the twentieth century, everyday items such as newspaper clippings, photos, cloth, and other materials began to take on both compositional and, at times, narrative commentary. For such non-representational works, including collage, assemblage, and combinations of two- and three-dimensional elements, composition was of central importance. Lacking an easily “understood” narrative or central religious element, something else was needed to draw, excite, or hold viewers’ attention.

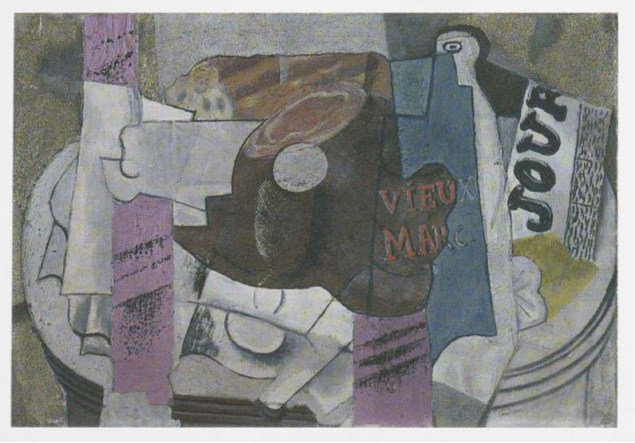

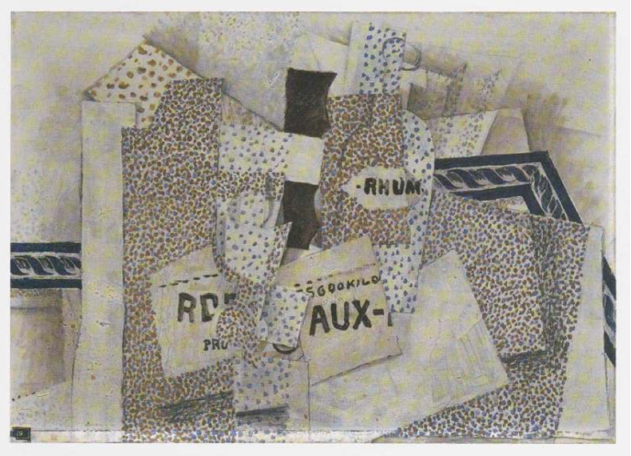

Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso were central figures in the development of modern and contemporary art. Working together between 1907 and World War I, the two developed new compositional techniques in cubist painting and collage that still referenced more traditional artistic tropes.62 Below are two fine examples of the novel projects they created, made in Paris in the spring of 1914. The Picasso is a painting on canvas of a collage-like composition, while the Braque is a work of painting and collage using sand on canvas.63 Both represent everyday objects, though each was painted rather than displayed as collage. In both works, the compositions lack a traditional focus. Each contain items that run off the edge of the canvas, cover most of the surface of the works, and juxtapose cleverly, leading one’s eyes to run riotously across the surface and tumble in all directions as a viewer ponders them for a time. They are, in short, untraditional, modern, eye-catching, animated, and political.64 But their compositions nonetheless are riveting, in part because they, like their medieval predecessors, used applique technique as a central compositional theme. By a century ago, Western art had reached the point where composition was ready to leap off the page into assemblages and combinations of traditional paintings with objects or even architecture.

Three-dimensional art evolved through similar transitions, though the compositional issues were often more complex. The compositional instincts of ancient sculptors, such as those constructing Stonehenge, are sometimes complicated and obscure to contemporary viewers. Later sculpting of religious figures and objects, especially in altar settings, frequently took on triptych compositional configurations, sometimes in large and multifaceted ways. The altar piece pictured below is one of many examples.65Whether occupying large spaces or a small niche, the environment in which a work was placed had an outsized impact on the way viewers perceived and comprehended the art itself. That compositional instinct, while surfacing at times with two-dimensional works produced for display in specific sites, is a more persistent factor in the creation and placement of three-dimensional works. From their use in religious settings, through their placement in particular secular locations, through recent tendencies to render sculpture using everyday objects, to their siting as abstract forms in open spaces, the intention is to grab and provoke our visual attention. Three-dimensional forms are often placed in unconventional settings—away from walls or in the middle of rooms—making the process of walking around them a critical part of the visual experience.

The work of contemporary artist John Chamberlin is a notable example of the use of everyday objects in three-dimensional art. Many of his pieces are composed of crushed and twisted parts of automobiles welded and bolted together in fascinating and joyous forms. Below is an image from a 2012 retrospective exhibition of Chamberlain’s work at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City,66 followed by another from a 2000 show of his work at the Pace Gallery, also in New York City.67 The Dia Beacon museum in Beacon, New York also routinely displays his work.68 In all three settings, it is not possible to fully comprehend many of the works without circumnavigating them. And their placement with other Chamberlain works is an integral part of the overall viewing experience.

For many stand-alone, two- or three-dimensional works, their setting is not necessarily critical to the way in which a viewer perceives them. Though their placement in certain rooms or near compatible works may enhance or diminish their artistic power, especially with three-dimensional works, many are largely capable of carrying their own creative authority without much environmental assistance. A single Picasso collage or Chamberlain sculpture can be placed in an array of spots and retain remarkable attraction to the human eye. But compositional sensibilities change dramatically when site-specific works come into view.

B. “Site-Specific” Works

For purposes of this essay, the most important compositional features present in many artistic endeavors arise in “site-specific” works. Intentional location in a particular place is central to their aesthetic power. Site-specific works create unified compositions combining surfaces—canvases, walls, or horizontal planes—with three dimensional forms—sculpture, architectural spaces, or landscape designs. The most extreme examples involve sculpting the earth itself. Robert Smithson,69 Nancy Holt,70 and Michael Heizer71 have sculpted huge parcels of land into vast vistas. These works cannot be moved—they are a part of the landscape that they inhabit. While di Modica can never claim that Charging Bull is as tightly connected to a site as the work of these earth artists, he does claim that the bull only attains its fullest symbolic power when placed in certain spaces with no other works to detract from or alter the perspective of viewers.

Site-specificity has been a critically important feature of many works for centuries. Altar pieces are obvious examples. Their removal to new locations or disaggregation for purposes of selling each part separately significantly detracts from or even destroys their intended religious power and compositional authority. The Dance by Henri Matisse, made for the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia and pictured below,72 is another renowned site-specific work made to be displayed in the particular arched doorways where it is currently located. Removing the work from this site would destroy the magnificent impact of the dancers gracefully flowing from lunette to lunette.

Similar consequences would arise if Claude Monet’s Water Lilies paintings were moved from their present location at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris.73 The space itself was designed in accordance with Monet’s desires. The final dedication of the space took place in 1927, one year after the artist’s death.74 As the museum notes, the environment helps evoke a powerful set of images and themes:

According to Claude Monet’s own suggestion, the eight compositions were set out in the two consecutive oval rooms. These rooms have the advantage of natural light from the roof, and are oriented from west to east, following the course of the sun and one of the main routes through Paris along the Seine. The two ovals evoke the symbol of infinity, whereas the paintings represent the cycle of light throughout the day.

Monet greatly increased the dimensions of his initial project, started before 1914. The painter wanted visitors to be able to immerse themselves completely in the painting and to forget about the outside world. The end of the First World War in 1918 reinforced his desire to offer beauty to wounded souls.

The first room brings together four compositions showing the reflections of the sky and the vegetation in the water, from morning to evening, whereas the second room contains a group of paintings with contrasts created by the branches of weeping willow around the water’s edge.75

During a more recent renovation of the museum from 2000 through 2006, Monet’s paintings, too large to move, had to remain in place.76

Meanwhile, di Modica’s claims about Charging Bull involve a somewhat more complex contention—not that his work is aesthetically well suited for display in a particular space, but that its cultural content requires placement near the epicenter of the nation’s financial markets. The bull’s symbolism is so tightly related to the N.Y. Stock Exchange and its environs that placing it somewhere else, di Modica claims, is inappropriate. Furthermore, he argues, allowing other works like Fearless Girl to be placed nearby reduces the power of the work’s intended symbolism and, thus, should be barred.

There are a number of site-specific works that raise similar issues. Consider, for example, the Statue of Liberty, formally dedicated in 1886.77 Its size and location at the entrance to New York harbor makes it easily visible to arriving ships and spectators on surrounding shores. This location has played a significant role in the statue becoming both an iconic symbol and a renowned work of art.78 Placed in Times Square, the statue would acquire entirely different and less evocative symbolism. The famous inscription on its base—“Give me your tired, your poor. Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”—would lose much of its rhetorical power.79

Landscape artists or architects sometimes create remarkably symbolic, site-specific sculptural works. And of course, sculptors and architects often work together to craft projects. In all these works, moving the three-dimensional forms from their original sites destroys a significant part, if not all, of the works’ original visual and symbolic power. An extremely powerful connection between sculpture and site is evoked by Maya Lin’s Vietnam Memorial in Washington, DC.80 With one of the work’s axes pointing to the Washington Monument and the other to the Lincoln Memorial, the work is a gash in the earth, invisible from behind, and framing a gradual decline from the front.81 The wall is both funereal and magnetic, drawing people to solemnly walk its length, to touch and trace the names of family members and friends, and to leave tokens of love and respect. The designed shapes of the earth and the wall are tightly integrated. They are “one” work—a moving, emotional space.82 Its artistic, compositional contours are intimately tied to the site.83

Bottom: Visitors observing names of 58,000 American servicemen etched into marble at the site.

III. Charging Bull and Copyright

A. Terms of the Legal Debate

Where does Charging Bull fit in this complex configuration of artistic composition and environmental location? It certainly is easy to imagine the di Modica work sited in a museum gallery. In that setting it would retain its aesthetic power and, with the help of a note installed nearby, still convey a message of American resilience in troubled times. It cannot be denied that in such a setting, di Modica owns intellectual property interests in the three-dimensional sculptural work. But does he also retain some or all control over where and how the museum may display it? In other words, does he own something more than a copyright interest in the object itself? Are there merits to his contention that museum or other displays of Charging Bull may violate his right to control the work’s environment?

At the other end of the spectrum, Charging Bull is not a wholly site-specific work. Di Modica cannot claim to be like Maya Lin—a designer of both a sculpture and its environment.84 Nor is he similar to Monet who worked in collaboration with an architect in the 1920s to craft a special environment for his Water Lilies.85 Di Modica was never involved with another person or institution to create a site-specific display for Charging Bull.86 Quite the contrary. Recall that he placed the work on Broad Street, directly in front of the N.Y. Stock Exchange, in the dead of night without the cooperation of or permission from anyone other than those who performed the tasks associated with moving and placing the work.87 Certainly, the location at the N.Y. Stock Exchange was integrated with di Modica’s commentary about resilience in times of economic hardship. But that particular site is not the only place where a similar message may be evoked. If he has any compositional claims beyond the sculpture itself, they must arise from a feature of the work that requires its location in a certain type of space or that necessitates limitations on the ability of others to “comment” on the art. That set of issues—both compositional and copyright-based—is considered next.

There is some logic in di Modica’s position that the ideal location for Charging Bull is close to, if not within sight of, the N.Y. Stock Exchange. It is after all a sculpture that literally expresses the notion of a “bull market” in making a statement about American resilience in troubled times. There is also some logic in his position that placing other works, such as Fearless Girl, close to Charging Bull alters di Modica’s apparent or perceived artistic intentions and injects quite different social and cultural messages. The bevy of onsite reactions to both the bull and the girl make that quite evident.88 Whether either of di Modica’s claims—that he controls the physical location of Charging Bull and holds the power to insulate the work from onsite, critical, artistic commentary—can be resolved in his favor under U.S. copyright law is unclear.

Two provisions of copyright law are critical to the analysis—the concept of a “derivative work” and the contours of moral rights law. The code defines a “derivative work” as “a work based upon one or more preexisting works, such as a translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion picture version, sound recording, art reproduction, abridgment, condensation, or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted.”89 If a person makes a work that recasts, transforms, or adapts a preexisting copyrighted work without the permission of the author of the original, it is an infringement.90 Di Modica may claim that the presence of Fearless Girl near Charging Bull recasts, transforms, or adapts his sculpture in two ways: by transforming the compositional environment in which the bull is displayed; or by recasting the symbolic importance of the sculpture.

Moreover, the moral rights section of the code provides that an artist during her life has the right “to prevent any intentional distortion, mutilation, or other modification of that work which would be prejudicial to his or her honor or reputation.”91 Here, di Modica must raise concerns similar to those made in his derivative work contentions—that placement of Fearless Girl or other artistic statements close to or upon Charging Bull so substantially recasts the bull by modifying it in ways that prejudice di Modica’s honor or reputation. Fearless Girl so profoundly distorts his artistic intentions, he might claim, that such commentary should be barred.

B. Compare Guernica: Artistic Intention, Location, and Moral Rights

To begin the inquiry, consider the connections between Charging Bull and Pablo Picasso’s famous Guernica, pictured above.92 The Guernica story is an important comparison for two reasons. First, like Charging Bull, there were disputes over the work’s location. Second, when pressure to move Guernica to Spain increased during the 1970s, Picasso’s heirs made moral rights claims about the work.

The history of Picasso’s work is complex. In 1937, Picasso painted Guernica—a huge, mural-sized piece measuring 11’6” by 25’7”.93 At the time, the Spanish Republican government was in the midst of a civil war with the Francisco Franco-led Nationalists—one of a number of fascist movements gaining power across Europe. Early in 1937, Picasso was commissioned by the internationally recognized Republican government of Spain to create a work for display in the country’s pavilion at the Paris Exposition scheduled to open later that year. Then living in Paris, Picasso was unsure about what to produce for the show.94 But on April 26, a unit of Germany’s Luftwaffe, loaned to and under the control of Franco’s forces, carpet-bombed the small town of Guernica, located not far from Bilbao in the Basque country of northern Spain. Hundreds, if not thousands, of innocent people were killed and wounded.95

The bombing of Guernica galvanized Picasso to work on the well-known painting named for the town.96 Picasso’s leftist political leanings moved him to compose a painting protesting both the bombing of Guernica and the rising fascist movements on the continent. When the Paris Exposition ended, “there was no indication that Picasso had become either precious or obsessively protective about the painting. It had a job to do. It was as simple as that. And like a theatre backdrop, it could be easily untacked and rolled round a tube ready for transport.”97 And so, Guernica went on tours in Europe and other parts of the world to raise funds for the support of refugees from the Spanish Civil War. When Franco’s forces took over Spain in 1939, the work was on display at the Museum of Modern Art (“MoMA”) in New York City as part of a retrospective exhibition.98

The painting remained at MoMA throughout World War II. During the early 1940s, Picasso requested that the museum serve as its guardian to protect it and to ensure that it would not be returned to Spain until “the reestablishment of public liberties” occurred there.99 If he became unable to make such a decision, Picasso entrusted his lawyer, Roland Dumas, to determine when that condition was fulfilled. MoMA oversaw additional tours of the work until 1958, when MoMA’s staff deemed it too fragile to withstand further travel.100 Guernica then remained at MoMA until its final move to Madrid in 1981. Arranging Guernica’s last move was not without controversy.

As early as 1968, Franco sought to have the painting brought to Spain.101 Picasso quickly refused that request, saying the move could not occur until democracy was restored in Spain. Picasso died in 1973, followed two years later by Franco. In 1973, Franco had designated Juan Carlos, grandson of the last reigning king of Spain, as his successor.102 Surprising many after he took over in November 1975, Carlos began the process of recreating a democracy. In 1977, the first general election was held. A new constitution went into effect the following year. In February 1981, an abortive military coup d’état was peacefully averted when Juan Carlos convinced the vast bulk of the armed services to stay on the sidelines. The first peaceful post-election transfer of power occurred the following year.

Though Spanish pressure to send Guernica to Spain began in earnest after Franco’s death in 1975, various roadblocks delayed the move another six years. Concerns raised by Dumas and four heirs of Picasso, delays by the MoMA, and practical issues about how and when to move the fragile work also caused problems. Both Dumas and Picasso’s heirs were concerned about the stability of Spain’s fledgling democratic government during and after the 1981 coup attempt.103 The heirs also claimed the right to control the painting’s whereabouts under French moral rights law.104 In addition, some heirs raised questions about whether Spain actually owned Guernica.105 If Spain could not confirm its ownership of the work, Guernica would have fallen into Picasso’s estate, a result of obvious benefit to the heirs.

Adolfo Suárez González, the first elected Spanish prime minister after Franco’s death, appointed the veteran diplomat Rafael Fernandez Quintinella to verify that Spain held the strongest tangible property ownership claim to Guernica. He did so in 1981 by discovering documents confirming that Spain had paid Picasso about $6,000 to create the work for the Paris Exposition.106 In 1981, with their concerns about the strength of Spanish democracy and the work’s ownership chain assuaged, the heirs consented to moving the painting to Madrid. This occurred at a June 1981 meeting in Paris, convened by MoMA, where all relevant parties were present, and the documents confirming Spanish ownership of Guernica were on hand.107 Dumas signed off on the details of the move in August, after the parties resolved insurance, transportation, and security issues. Guernica arrived in Madrid and became available for viewing by the public on October 25, the centennial of Picasso’s birth.108

It was only after the 1981 meeting’s resolution of the potential disputes between MoMA, Dumas, and the heirs over moving Guernica to Spain that a complex legal dispute was avoided. In reality, each side raised issues about the same problem—the location of the work. Dumas claimed that Picasso’s desires should govern the outcome of the dispute, and that his oft-stated wishes governed both the meaning of the art and the propriety of its display in Spain. The heirs claimed that, as successor defenders of Picasso’s moral rights in the painting, they controlled the decision about Guernica’s location. Recall that in France, transfer of moral rights, either by an artist or an artist’s successors, is generally barred.109 According to the heirs, prematurely moving it to Spain would not only undermine Picasso’s intentions but would also alter or mutilate the meaning of the work itself.

Di Modica makes very similar claims about Charging Bull, declaring that his ownership of the work’s intellectual property and the associated moral rights gives him control over the proper location for his work and the artistic environment that may come to surround the piece.110 The factual underpinnings for the disputes over location and environment emerge in both cases from statements and desires enunciated by the artists themselves.

There are, of course, significant differences in the story lines of the two works. Di Modica deposited his work unannounced on a city street. Picasso was commissioned to make a work. Di Modica objected to the relocations of his work, but Picasso was much more precise about the reasons for his desire to permanently display Guernica only in Spain. Because of its outdoor location, di Modica’s work became an easy target for direct artistic confrontation and commentary. Picasso’s work was rarely a physical target or a subject of onsite, artistic efforts to interpret or reinterpret its meaning.111 Unlike Charging Bull, another work of art directly commenting on Guernica and intentionally placed nearby has never appeared. Di Modica never made arrangements with persons in authority to create or monitor the sculpture’s placement. Picasso, in essence, appointed the MoMA, then voluntarily the custodian of Guernica, as its guardian.

The two works are, however, similar in at least three important ways. First, neither work has ever been displayed in a site specifically designed for an artistic contribution by the artist. Second, the closest either of the artists came to stating a preference about where their work should be displayed was to describe an area or a city. Put another way, both di Modica and Picasso only stated their general desires (near the N.Y. Stock Exchange and in Madrid) about placement of their creations. Third, neither di Modica nor Picasso made statements about where their works should be located until some time after they were first displayed to the public. They definitely were not site-specific creations. What is the impact of statements of intention made after a work’s initial installation on the contours of the copyrights in either or both works? Do statements of intention about a work made after its initial installation and display alter its compositional or other artistic characteristics in ways that enhance the likelihood that works placed nearby constitute derivative works? Does a similar impact arise in the moral rights context?

C. Copyright, Intention, and Location

1. Intent

Artistic intention has long been relevant to determining the scope and contour of copyright protection in the United States.112 It is especially pertinent to disputes over the relevance of artists’ statements about the location of works that were not originally fashioned as site-specific creations. In these cases, a work’s extant location may not clearly present inferences about the artist’s preferred placement. Additional issues arise because the most important court opinions about copyright and intent are not about painting or sculpture. Exploring the disputes over Charging Bull and Fearless Girl therefore requires some thought.

One of the most cited cases about artistic intention and its relevance to determining the scope of intellectual property protection arose in a dispute over the fact-expression dichotomy. Though it is a staple of copyright law that expression is protected while facts are not, the definition of “fact” for these purposes means something quite different from its standard use as a synonym for “truth.” A statement may be “factual” for copyright purposes not because it is true but because the author declares it to be factual. The best-known example of this strange phenomenon is A.A. Hoehling v. Universal City Studios, Inc.113 Hoehling wrote a book, which he described as historically accurate, claiming that the Hindenburg exploded in 1937 due to sabotage. In doing so, he rejected the widely accepted theory that static electricity caused the hydrogen-filled airship to burst into flames. When filmmakers later used his sabotage storyline in a movie, Hoehling sued for copyright infringement. The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit concluded that the tale Hoehling labeled as factual was not copyrightable.114 The storyline (but not Hoehling’s expression of it) was left in the public domain under the copyright code provision barring protection for “any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery.”115 Facts are treated more like ideas, concepts, or discoveries than as expression.116 They are the cornerstone for conversation, politics, life, and culture—the sorts of discourse necessary for the maintenance of a flourishing public forum. While the form of a “factual” story—its expression—could be protected, the storyline itself was available for use in general civil discourse and other creative, expressive works.

Note well that the Second Circuit never made an actual determination that Hoehling’s story was true in any epistemological sense. Again, his version of the tale was widely considered inaccurate. The court merely held that the author’s description of the story as “true” resolved the issue of copyrightability. Hoehling’s statements—his intention—determined the scope of the book’s intellectual property protection.

At first glance, this conclusion is difficult to justify. How can the law classify a story as factual for the purposes of copyrightability when virtually everyone who knows about the events in question declares it to be false? Over the centuries, the search for “truth” has been one of the most slippery tasks humanity has tackled. Is the Hoehling “solution” simply an efficient way for courts to avoid participating in the philosophical debate? For copyright purposes, this strategy might work tolerably well.

But the Hoehling result may also cause nightmares. On the one hand, it creates an incentive for artists and authors to label material as non-factual, thereby permitting intellectual property protection over their purportedly original, expressive works. On the other hand, consider a Hoehling-opposite dispute in which an author labels a story as fictional even though virtually everyone else in the world views the tale as true. This Hoehling-opposite case might well lead to a finding of non-copyrightability. What justifies granting an author protection for a story that has previously been in the public domain as a factual tale? If followed, the version generally recognized as accurate would be barred from use by anyone other than the author labeling it as false. Intent as a copyright guideline almost surely has its limits, especially with regard to issues of truth.117

Nonetheless, the underlying notion that intention has a substantial impact on copyrightability cannot be gainsaid.118 Consider another example, this one pictorial. Suppose an abstract artist has a canvas in her studio leaning against a wall that she painted over years ago with white gesso—a substance often used as a primer upon which to paint a composition. After painting on the gesso, she set it aside and never got around to using it. In that hypothetical setting, it probably is not an original work eligible for copyright protection.119 Though the level of originality required for protection is quite low,120 a gesso-covered canvas leaning against a studio wall for years probably does not suffice. But what happens if the artist looks at the canvas after ignoring it for all these years and concludes that she now really likes the way she brushed the primer onto the canvas, gives it a name (say “Composition #36 in White”), and places it in an exhibition of her work at an important gallery? That step is a statement of intention that she thinks of the piece as a work of art. The likelihood that it is now original increases dramatically. There are many important and widely praised white canvases by well-known artists hanging in important museums around the world.121 While the search for the meaning of originality is often as open-ended as that for intention, there can be little doubt that the intention of an artist has an impact on the scope of originality. Just as a writer’s statement claiming a work to be factual may lead to a conclusion that a book is not copyrightable, so may an artist’s claim of beauty make her work both expressive and original.

Such examples help explain why the scope of protection for the works of di Modica and Picasso is much more challenging to decipher than in the case of Monet’s Water Lilies at Musée de l’Orangerie. The intentions of Monet were unequivocally concerned with both the painted images and their environment. He worked closely with the architect, Camille Lefevre, who in 1922 crafted plans for remodeling the l’Orangerie building into a viewing space for art.122 The museum describes the links between the paintings and the rooms in which they are displayed to this day in this way:

From the late 1890s to his death in 1926, the painter devoted himself to the panoramic series of Water Lilies, of which the Musée de l’Orangerie has a unique series. In fact, the artist designed several paintings specifically for the building, and donated his first two large panels to the French State as a symbol of peace on the day following the Armistice of 12 November 1918. He also designed a unique space consisting of two oval rooms within the museum, giving the spectator, in Monet’s own words, “an illusion of an endless whole, of water without horizon and without shore”, and making the museum’s Water Lilies a work that is without equal anywhere in the world.123

Under contemporary American copyright law, this statement by l’Orangerie is highly likely to support a conclusion that Monet and Lefevre were authors of a joint work—“a work prepared by two or more authors with the intention that their contributions be merged into inseparable or interdependent parts of a unitary whole.”124 Put another way, the paintings and the environment in which they are still displayed are inseparable parts of the same original work. Removing the paintings from the architectural space would be a significant mutilation of the original work. That step would undermine the intentions of both Monet and Lefevre and probably violate the terms of American moral rights law if done in the United States during the lives of the artist and architect. The paintings and the rooms in which they hang are a unified compositional undertaking. Under the statute, an author may “prevent any intentional distortion, mutilation, or other modification of that work which would be prejudicial to his or her honor or reputation.”125 Similarly, modifications made to the environment in which Monet’s paintings are displayed would create a derivative work, not only of the architectural work, but also of the joint work that includes the paintings themselves.126 If the modifications were made without the permission of the authors, it would be an infringement. In short, place and painting may be linked in intimate and jointly copyrightable ways. The locational intentions of di Modica and Picasso, however, are much less well-defined.

2. Derivative Work

Di Modica, recall, claims that others will violate his right to control the creation of derivative works of Charging Bull if they change the work’s location. That is a difficult challenge to meet. Di Modica simply left his sculpture in a publicly accessible space for what he thought would be a short-term stay.127 He also announced the work was a gift to the city. These actions are hardly evidence of intent about siting the bull in an aesthetic environment for the long term. Instead, di Modica’s overnight placement of the work was more like commandeering a site than helping to craft one. Further, after Charging Bull was removed, di Modica enthusiastically consented a short time later to placing it in a new location at Bowling Green, several blocks away from the N.Y. Stock Exchange. If he has any control over location, it must be limited to an area, not a specific place.

In the absence of a contractual agreement between di Modica and the city about the permanence of Charging Bull’s current location at Bowling Green, it is unlikely that di Modica has any control over future siting decisions. It would stretch expression in copyright law to the breaking point to allow an artist to deposit a work in a public space, enthusiastically support its movement to another public location with the blessing of public officials, later proclaim that the work is legally and permanently bound to that location, and then top it all off by demanding that no other works of commentary be placed nearby. While di Modica may bar others from making souvenir models of his work, it is quite doubtful that he can control broader aspects of the bull’s location under copyright law.

Similarly, di Modica’s after-the-fact declaration that he has the power to preclude movement of Charging Bull to a new location without his approval also stretches the power of intention in copyright law to the breaking point. While di Modica approved of the bull’s move to Bowling Green, that consent does not change the compositional contours of the work. There is nothing unique about Bowling Green that adds to the artistic qualities of the sculpture. It is difficult to see how it is an original addition to the pre-existing work that might make the location part of a new derivative work. If anything, the work’s subsequent move detracted from the work’s original novelty by moving it further from the N.Y. Stock Exchange and that institution’s connection to bull markets.

Picasso’s Guernica presented similar predicaments. Picasso did enunciate a location preference for Guernica, but only after Franco’s forces prevailed in the Spanish Civil War and World War II began. As the Public Broadcasting Service so eloquently noted, Guernica became a refugee just like so many others during World War II.128 As with the bull, can such after-the-fact declarations be allowed to modify the copyrightable, compositional contours of a work and thereby create something derivative? Given the circumstances in which a willing party (MoMA) took custody of the painting and promised to follow the wishes of Picasso, there was some artistic control over the future location of Guernica. But that control did not arise naturally from the scope of copyright protection held by the artist. It arose from a separate contractual or trust-like undertaking between Picasso and the MoMA.129 In addition, calling for Guernica to be located in Spain hardly referred to a well-defined space. May such a statement of intent and desire about location made long after a work’s creation and public display in an array of locations be considered a modification of an underlying work that creates a new derivative work? Or is it simply a moral statement—an “ethical will”—that creates a social, and in this case political, sense of obligation? Indeed, the same questions may be posed about Charging Bull, especially since it was relocated to Bowling Green in large part because of negative public reaction to carting it away from the N.Y. Stock Exchange and placing it in storage.

For similar reasons, moving either work probably does not violate any conception of moral rights unless the new location serves to undermine the reputation of the artist. Given the somewhat haphazard process by which both di Modica and Picasso dealt with the location of their works during the time following their creation, it is difficult to see how the reputational authority of either di Modica or Picasso would be disturbed. In neither case may an element of their artistic creativity be decided by such post-creation statements of intent.

D. Copyright, Intention, and Proximate Artistic Commentary

Though it is difficult to justify giving either di Modica or Picasso management over the particular places their works are displayed under copyright law, there are other ways they may maintain some control over the nature of the spaces surrounding their original works. The same rule structures discussed above—moral rights and derivative works—are in issue here as well. Reconsider the Charging Bull/Fearless Girl tale by picturing the girl placed eye-to-eye with and a quarter inch away from the bull—something like this:130

This placement of Fearless Girl is a much more direct confrontation to Charging Bull than its original location some yards away. Di Modica, recall, claimed that both the original location of Fearless Girl at Bowling Green staring down Charging Bull and the proposed relocation of his work to the N.Y. Stock Exchange not far from the present location of the girl violate his rights to control the making of derivative works and his moral rights in the sculpture.131 By moving Fearless Girl to a spot directly in front of the bull, the compositional impact on Charging Bull rises dramatically. Viewing one piece simultaneously requires looking at the other. They arguably become more like a single composition. This raises the stakes for both claims. Perhaps decoding this example will shed light on the actual settings involved in this dispute.

1. Fearless Girl as a Derivative Work

A derivative work is defined in the statute as “a work based upon one or more preexisting works, such as a translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion picture version, sound recording, art reproduction, abridgment, condensation, or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted.”132 From earlier discussion of Monet’s Water Lilies at l’Orangerie and Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial133, we already know that a two- or three-dimensional art object may include within the parameters of its copyright areas outside the particular object itself, especially if the artist has a well-articulated intention to broaden her artistic frame of reference. Thus, the copyrightable scope of a work placed in a building designed for it or a work that is a combination of a number of objects in a particular setting may extend beyond the limits of that particular two- or three-dimensional work. The code also gives the holder of copyright in such an original work the right “to prepare derivative works based upon the copyrighted work.”134 Outsiders may not unilaterally make a derivative work in the absence of fair use.135 Presumably, therefore, an artist may approve (or disapprove) as a derivative work an “addition” to it that is outside the exact physical limits of the piece while still having the effect of recasting, transforming, or adapting the original. The dramatization of a novel performs a very similar role. By placing the book version in a new spatial setting with altered linguistic characteristics, a play makes use of the original while recasting and transforming it. Similarly, there is no reason why an artist may not claim the right to control some aspects of adjacent works if they also recast or transform the original. Di Modica’s argument, that he enjoys some level of control over works located near his bull, is therefore not without credence and different from his claim about location. Exactly what the scope of such protection may be is as ineffable as the artistic notion of composition. Proximity and compositional authority speak with related tongues; logical results, therefore, may be difficult to discern.

For example, suppose di Modica had rendered another bronze sculpture of a woman that raised sensibilities quite different from Fearless Girl. Picture a bold figure of Sojourner Truth standing beside the bull with one arm wrapped supportively around its neck. Truth, born into slavery in 1797, escaped from bondage in 1826 to become a critically important leader in the abolitionist and women’s civil rights movements before her death in 1883.136 Placing a statue of Truth next to Charging Bull would present a quite different image about gender than Fearless Girl. Rather than confronting the bull, Truth would portray a message supportive of di Modica’s original intention about American resilience in difficult times, while reducing the masculine qualities of a bull standing alone with a somewhat threatening countenance.

(c. 1864)

The Truth work, viewed together with the original bull, would be a derivative work. The work would recast di Modica’s original bull by adding compositional and cultural implications to his message about resilience. An artist other than di Modica who made and installed such a sculpture without his permission would be infringing—just as a play made from a novel without permission would be infringing. For similar reasons, the placement of Fearless Girl eye-to-eye, directly in front of the bull might also be derivative—as a critique of Charging Bull but nonetheless derivative. Such a conclusion rests on one pivotal supposition—that an artist has some control over the spatial and compositional characteristics of artistic works in the area surrounding a creation that may recast or transform the nature of the original work. Given the analysis to this point that is a logical and appropriate conclusion about the meaning of artistic composition, the nature of artistic spaces, and the impact of artistic intention.

How far does this legally protected compositional space extend? Surely it would be inappropriate to conclude that a museum could never mount an exhibition without obtaining permission from all artists whose work is scheduled to be shown in the same room. One creative soul should not have the ability to veto showing the work of another because it connotes negative commentary on the first. Each work must have its own arena of compositional authority. Implicitly, this suggests that the two Fearless Girl cases posited here—one with the girl placed across a square and the other with her standing belly to nose next to the bull—might not be treated the same way.

Given the impetus in American culture to encourage open discussion and critical commentary about artistic works, the extent of spatial control by one artist over the creations of another, sited without the knowledge or participation of the original artist, should not be extensive. While placing Fearless Girl adjacent to Charging Bull might well infringe upon di Modica’s derivative work rights, locating Fearless Girl some distance away from the bull probably does not. Kristen Visbal, the sculptor of Fearless Girl, and State Street, Visbal’s financial backer, certainly were free to critique di Modica’s use of masculine imagery about financial markets as a symbol of American cultural persistence and resilience. While they may not be free to place their critique directly adjacent to and almost touching the bull, locating Fearless Girl across a plaza should be permitted. And, even if the placement of Fearless Girl across a plaza is derivative, its critical observations are surely fair use, even if its power as a symbol of gender diversity is tainted by its sponsor’s own history.137 Crafting of social and political commentary is archetypal activity protected by the fair use doctrine.138 Though Fearless Girl may transform the imagery of the bull, it does so in a productive burst of controversial social commentary typically protected by the doctrine of fair use. Note well that when placed some distance apart, each work may be perceived either independently or in tandem, either as a solitary cultural comment or as combined evidence of social conflict. The echoes of compositional power are strong but not insurmountable.

2. Fearless Girl and Moral Rights

A similar outcome arises under moral rights concepts. Placement of Fearless Girl directly adjacent to Charging Bull significantly alters the compositional power of the larger sculpture. While not destroying the bull, this placement of Fearless Girl may “mutilate” the original work. Though not physically altering the sculpture as the banjo-wielding Texan did, the girl modifies the force and power of di Modica’s intentions for the bull and weakens his compositional authority. Neither “mutilation” nor “modification” is defined in the copyright code. But given the importance of spatial composition—the artistic ability to encompass a volume of space outside the physical boundary lines of a work—it would be quite strange if placing one work directly next to another could never be a modification or mutilation. The more difficult problem is deciding whether such a step “would be prejudicial to his or her honor or reputation”—a requirement for protection under the moral rights provision of the statute.139

The most frequently cited case on the meaning of “prejudicial to his or her honor or reputation” is Carter v. Helmsley-Spear, Inc.140 Using common meanings given to the phrase, the Carter court concluded that reputation may refer to both the artist and the work at issue, and that the artist need not be well known to claim rights under VARA. Rather, the focus is on whether alteration or mutilation of a work “would cause injury or damage to plaintiffs’ good name, public esteem, or reputation in the artistic community.”141 A coherent argument certainly may be made that placement of Fearless Girl directly adjacent to Charging Bull would humble, if not demean, the power of the original work and thereby diminish its reputation in the community of visitors, artists, and critics.142 The presence of Fearless Girl insinuates that the optimistic view of American resilience di Modica intended to convey would wilt, replaced by an image of the powerful bull diminishing the experience of women. The closer the girl is to the bull, the more powerful is its ability to diminish the reputation of the original work and its artist.143

Conclusion

This essay has revealed a critically important truth about the relationships between copyright law, two-dimensional art, sculpture, and architecture. Too often, the copyright law of pictorial works is considered easily separable from the copyright law of sculpture and architecture. There is a reason why so many people hang pictures on their walls and place decorative objects on surfaces shortly after moving into a new home. Those images help to define the nature of walls, transforming a room into a living experience and giving the architecture of a space depth and meaning. Traditional wall and table-top art define space, and space defines traditional wall and table-top art. In day-to-day lived experience, a space and the objects in it cannot be quickly and easily aesthetically separated. They are an interconnected, lived reality.

Taking that idea into account alters the ways we typically apply copyright law. Rather than viewing a traditional painting as independent of the space in which it hangs, the art and the environment should more frequently be considered as a combined entity. In our homes we may act like curators mounting exhibitions, considering the nature of each painting, their relationships to other pieces in the room, and the impact of each work on the display space. The success of an exhibition can rise or fall depending on the sophistication of the curator’s arrangement.

These relationships between a single work, nearby compositions, and the space in which a group of works are displayed should routinely be taken into account when evaluating the meaning of copyright “terms of art”144 like “compilation,” “collective work,” “work of visual art,” “derivative work,” or “moral rights.” In each case, analyzing a single work without regard to its environment may overlook important aesthetic considerations, especially the nature of artistic composition. Charging Bull and Fearless Girl forcefully convey this idea. When placed in close proximity to each other, they are no longer standalone objects. They become parts of a composition in ways that may have a critical impact on the application of copyright law.

Intuitively, we sense this as we stroll around certain environments, especially urban historic neighborhoods. Most preservation laws require that the design of a new building in a protected historic area be reviewed and approved by preservation authorities before construction begins. Debate about whether a proposed structure “fits” with a neighborhood is essential to deciding whether it may be built. Is it designed to be contextual and fit with aesthetic features of the existing environment? Does it “clash” with the neighborhood’s ambiance in acceptable or unacceptable ways?

One of the most interesting examples of this problem mirrors the Charging Bull/Fearless Girl controversy. It reflects the sometimes-ineffable qualities of decisions about the meaning and impact of “composition” on aesthetic choices in architecture and urban planning—an arena tightly related to the world of deciding how best to place a sculpture in an appropriate environment. The original house at 18 West 11th Street in New York City’s Greenwich Village—an historic 1845 Greek Revival building—was destroyed in a 1970 explosion when members of radical leftist group Weather Underground were living in the building.145 A new house was constructed at the site in 1978 after a review by the Neighborhood Community Board and the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission determined that the plan was “appropriate.”146

As is evident from the picture above, the top floor of the new house is contextual while the first two floors are provocatively unusual. The jutting, angular bay is a vivid reminder of the dislocation and destruction caused by the 1970 explosion. Yet, the Landmarks Preservation Commission concluded that the new house was “appropriate.” Like the controversy over Fearless Girl, the new building raises questions about what level of commentary about neighboring architectural designs is acceptable. While the question on 11th Street involves historicity, the issues are quite similar to those raised by di Modica. What is the impact of compositional proximity and aesthetic commentary? The new house was only partially derived from the neighboring designs. Does that explain why the Landmarks Preservation Commission was both granted some control over its construction and eventually approved the design? Or is it so much in conflict with the overall ambiance of the block that its erection is similar to a moral rights violation—a mutilation of the neighborhood’s composition that should never have been built? Perhaps your answer to these questions about whether the new house at 18 West 11th Street should have been constructed will help you find answers to the questions posed in this Article about the Charging Bull/Fearless Girl compositional controversy. Reaching definitive answers, however, may best be left in the hands of those who love to dance on the heads of pins.

COMMUNIQUE RE GUERNICA

Issued in April 1977 by Maître Roland Dumas, Picasso Family Lawyer

The status and fate of Guernica—the famous painting by Picasso of 1937 executed following the destruction of the small Basque village by Nazi planes—is the object of unfounded rumors and speculation.

The commotion concerns, particularly, the sending of the masterpiece to Spain by The Museum of Modern Art in New York, where it has been on extended loan since September 1939 consistent with the wishes of Pablo Picasso.

Pressed by a request from the Spanish government for Guernica—which he deemed improper—Pablo Picasso charged me in 1969 with preparing documents describing his express wishes concerning the future of his picture.

Pablo Picasso confirmed in writing what he had already on several occasions declared—notably to Mr. Barr, the Director of The Museum of Modern Art in New York, and to Mr. Rubin, Director of that Museum’s Department of Painting—namely that “Guernica and its preparatory studies belong to the Spanish Republic,” but that the transfer to Spain could only be envisaged after the complete reestablishment of individual liberties in that country.

Pablo Picasso spoke of this decision on several occasions, both to his close friends and to the representatives of The Museum of Modern Art in New York, and to myself.

The fragility of the painting, he said, precludes any further travel after its installation in Madrid. Furthermore, he continued, a certain time should be allowed to pass to verify that once established, the democratic regime is no longer subject to a forcible coup which might reopen this question and that, finally, political relaxation should accompany a general détente.

All those who have heard directly from Picasso the instructions which he gave for Guernica are unanimous in believing that, while the wishes of the famous painter to see this prestigious work in Madrid were distinct and without ambiguity, he intended prudence in the realization of his decision.

He spoke to me numerous times about this anguishing subject. His preoccupation about Guernica took precedence over everything else. He furnished proof of this in agreeing to make arrangements in writing, which he has not done for any other problem touching on either his succession or his work. He did me the honor of confiding in me the responsibility of overseeing the execution of his wishes.

Admittedly, some progress had been realized in Spain. And a not negligible evolution has occurred since the death of General Franco. But I cannot consider that his evolution has as yet terminated.

Neither have the conditions posed by Picasso himself touching on the security of the paint and the stability of a new and totally democratic regime been achieved.

The transfer of Guernica, finally, demands manifold technical precautions. These arrangements will require several months from the day when the decision of transfer shall be made.

For all these reasons and in accord with The Museum of Modern Art in New York which agrees to continue as “guardian”, a mission which was initially confided to it by Picasso himself, Guernica shall stay in New York, to remain there until a new order is achieved in Spain,

Consequently, its transfer to the Prado in Madrid—which is agreed upon in principle—cannot be realized for several years.

The present communication has been read to Rubin, Director of the Department of Painting of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, who has been good enough to agree to its terms.

Roland Dumas147