Richard Chused *

Download a PDF version of this article here.

Introduction

A vast amount of two– and three–dimensional fine art1—paintings, sculptures, and prints—is held in private locations and storage facilities remote from human sight. Much of it is deemed to be of superb quality and extremely valuable.2 Yet these works—whether treasured or not—sit year after year in whatever caches they occupy—art museum storage areas, secure off-site storage sites, isolated freeports,3 and privately housed collections—typically unavailable for viewing by the public—often by no one at all.4 In addition, much of the American public lacks access to any, let alone important, museums. Rural areas, small towns, and midsize and smaller cities often lack art museums open to the public.5 Moreover, many major museums charge admission fees that are beyond the means of a significant portion of the population, especially when the cost of transportation and parking is considered.6 Some institutional managers and art aficionados seem not to care. Should it be that way?

This article explores a single set of ideas that emphasizes the myriad ways in which human creativity is frustrated by the failure of American society to provide large numbers of people with ready access to art collections. It is the general public that is my primary concern here—its access to, understanding of, and benefits gained from seeing art and sculpture. Viewing art enhances civil society, allows for widespread cultural discourse, and encourages deeper and more thoughtful reactions to issues of public importance. Deep constraints on access to art foster barriers to human creativity, ingenuity, and progress—the very purposes copyright law is designed to enhance.7 The right to view art, in short, should be thought of as a public good, as a human right.8

This broadly stated goal to widen access to fine art is frustrated by an array of rules limiting the display of fine art derived from copyright law, property law, legally binding agreements, norms promulgated by museum organizations, customary museum practices, and lack of funds for museum development and growth in underserved areas. Artists, collectors, private and public museums, art galleries, auction houses, and other settings in which art transactions are consummated, as well as government agencies, may be reluctant to change. Auction houses, for example, routinely send important works off to anonymous buyers and unknown destinations—results desired by all interested parties. Institutional goals to amass collections, sell art, or maintain high prices often conflict with the notion of wide distribution of works they control. Efforts to change the legal rules about displaying fine art are bound to have an impact on all involved entities. The array of norms and interested parties render efforts to rethink art display practices challenging. The first part of this article discusses the theories underlying my aspiration to expand public access to art. That is followed by exploration of the variety of settings in which display issues arise, the impact of various constraints on expanding access to artistic works, and the possible pitfalls of undertaking significant efforts to do so.

I. Benefits and Burdens of Enhancing Access to Art

A. The Theory

Artists ordinarily want their work to be seen. When observed, viewers may be enthralled, aggravated, or befuddled for reasons they find difficult to express. The range of possibilities buried in such reactions—whether silent or expressed—is vast. Art may confirm viewers’ perceptions of the world, send them away in annoyance, transmit or redefine history lessons, communicate both intolerance and empathy, convey emotions, provide new ways of looking at or thinking about life, create a sense of amazement at the level of proficiency, wisdom, insensitivity, or beauty evident in a work, stimulate demands for cultural change, or [you fill in the blank]. The boundless scope of possibilities, by itself, supports the proposition that hiding large quantities of art from public view frustrates human advancement. And it may also frustrate the hope of artists that work they release for exhibition or sale will be seen, contemplated, and absorbed by a large number of people.9 A single in-person viewing of Picasso’s Guernica should confirm the importance of widespread public access.10

A work of art is difficult for a human mind to permanently “capture,” to fully understand, or to vividly recall later in all its detail and meaning. Even if an image of a piece is saved on an electronic device, the actual viewing experience can hardly be fully retained, the momentary understandings about the work gleaned from observation will evolve over time, and perceptions may be altered by later or repetitive viewing. Returning to see an image again, whether in person or electronically, will not necessarily recreate the original viewing experience; nor will it replicate reactions to an earlier encounter. This is especially true for paintings and sculptural works which ideally are seen from a variety of visual perspectives in galleries allowing for easy circulation in front of or around objects.

David Joselit’s recently published Art’s Properties provides an important reappraisal of the way we should think about, perceive, and view art. In the prologue of his book, he wrote:

If art cannot be captured by history, it may nonetheless generate unlimited narratives. In this regard, the museumgoer-photographer again demonstrates something fundamental: if the value of art can never be captured, nor can it be fully consumed. The power of art is its capacity—its infinite capacity—to generate experience over time.11

Joselit suggests the ability of art to produce changing experiences over our lifetimes should be treated as a public goods issue—the public’s need to experience and reexperience art over time should be protected beyond the present willingness of art owners to provide it, present understandings of the copyright code to require it, and contours of property law to compel it.12 Coping with the present, inadequate efforts to protect and enhance this public good, turns out to be a complex, non-obvious, and politically challenging undertaking.

The challenges were made painfully clear by the denouement of the most important and unique, but all too short-lived, national effort in United States history to substantially enhance public access to and understanding of art. Many of the cultural benefits of art’s accessibility were revealed in dramatic fashion during the short life of federally supported arts projects during the Great Depression beginning in 1934 and ending in 1943. These programs began in 1934 when the Public Works of Art Project was created to distribute grants for the creation of works in or on public buildings. The following year, it was broadened to include a variety of grants to artists as part of the Federal Arts Project (“FAP”) overseen by the Works Progress Administration (“WPA”).13 In that era, artists, like many segments of the public, were in the midst of significant financial struggles. While such difficulties were hardly unknown to the pre-Depression lives of many artists, the survival problems intensified during the 1930s.

The story is told that in 1933 when Harry Hopkins, who was placed in charge of work relief programs by Franklin Roosevelt, was flippantly asked whether artists should be considered as “beneficiaries” of the work program since they had no “jobs” to lose, replied, “Hell, they’ve got to eat just like other people!”14 But as the FAP was organized in 1935 under Holger Cahill, the first national director of the government program, it operated not only as a program for supporting artists in troubled economic times, but also as a way of making artworks broadly available to the general public—as a way of fulfilling the idea that widespread access to and creation of art was an important public good. It involved not only work in or on public buildings,15 but also teaching, community art centers, and various ways to support the basic needs of both artists and the general public.16

This desire to “democratize” the arts was a major theme of a series of essays written by those involved in organizing, operating, and influencing the operation of the FAP during the 1930s.17 Perhaps the most important of these essays was by Cahill, who was himself deeply influenced by the major American philosopher and pragmatist, John Dewey.18 Dewey’s best-known book on the relationships between aesthetics and society, Art as Experience, was published in 1934. Victoria Grieve, in her seminal book on the FAP, described Dewey’s theory:

When people experience their daily lives with the self-consciousness of artists at work, realizing life’s full potential for meaning and value, existence itself became an art. It was through the creation of significant, meaningful, and fulfilling lives that a truly democratic society functioned. Because art formed the basis of human experience, Dewey believed that a theory of aesthetics was “central to the philosophical project” and a crucial test of any philosophy’s ability to fully explain experience.19

While Cahill did not fully agree with Dewey’s proposition that life itself is art,20 he certainly believed artistic experiences are central to human development. In the introduction to the catalog for the first public exhibit of works created under the auspices of the FAP, for example, Cahill wrote:

[T]he works shown in this exhibition indicate important phases of a year’s accomplishment. From the point of view of the artist and the public they have a significance far beyond that of the record, beyond even value as individual works of art. Taken as a whole they reveal major trends and directions in contemporary expression, and a view toward new horizons. Surely art is not merely decorative, a sort of unrelated accompaniment to life. In a genuine sense it should have use; it should be interwoven with the very stuff and texture of human experience, intensifying that experience, making it more profound, rich, clear and coherent. This can be accomplished only if the artist is functioning freely in relation to society, and if society wants what he is able to offer.21

During the first year of the FAP, Cahill oversaw the hiring and supervision of over 5,000 artists, as well as the work they exhibited in their own studios and produced or performed for public institutions and displays. Mary Gabriel, in Ninth Street Women, another seminal work on major artists who emerged in the 1930s, noted the critical importance of the support they received, in part with the help of federal arts programs:

The Project kept painters and sculptors alive, but it had other unanticipated consequences. It created a community where none had previously existed. Suddenly artists who had worked in isolation began discovering one another. And it gave artists a sense of worth: For the first time, the government had recognized them as individuals with a talent that could benefit the broader society.22

The FAP, therefore, not only exposed the general society to more artistic works, but also helped develop a culture that encouraged artists in their work, broadened cultural awareness of struggling painters and other creative people laboring in related arenas, provided the support they needed to be more productive, and enhanced public interest in contemporary artistic endeavors. The entire culture benefitted. Indeed, there are scientific studies suggesting that widespread interest and experience in art, music, dance, dramatics, or other related endeavors, whether by making or doing things or by experiencing the work of others, is beneficial to the well-being, longevity, and brain health of everyone.23

Unfortunately for society as a whole, the FAP, like other New Deal programs, fell by the wayside during and shortly after World War II. Public opposition to government support of the arts as socialist and wasteful took its toll.24 By 1943, the great experiment ended. But the FAP had an enormous long-term impact on the survival, acceptance, and continuing appeal of mid-twentieth century and later art movements in American life.25 The increasing numbers of people now streaming to major art museums in large cities across the country to see both traditional works as well as new and contemporary creations is a testament to the dam-breaking impact of the FAP.26 It is those lessons that must be taken to heart in framing new rules about the display of art to the general public and crafting public support for increased access to the arts.27 The issue is deemed to be so important by the international community that a right to enjoy the arts has been included in The Universal Declaration of Human Rights.28 Article 27 provides: “Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.”29 Finding ways to fulfill this lofty international norm inspired the writing of this project.

B. Introduction: Roadblocks to Enhancement of Art Displays

Two recent news stories about large donations of two-dimensional art to major museums stimulated my initial recognition of the deep complexity involved in describing the extent of art in hiding, the sorts of restrictions often imposed on display of creativity, the large array of relevant institutions, and the challenges to refashioning common understandings. The first story told of an incredible collection that was eventually widely distributed to museums with no admission charge—one institution in each state. This heart-warming story did lead to widespread distribution of fine art to sometimes underserved areas; it did not, however, lead to the bulk of the huge collection routinely being on public view. Its large beneficial impact resulted from the decision by the collection’s owners to make their assemblage of art available to many institutions that did not house major collections. The result was broad access by segments of the public not typically exposed to the largely minimalist and conceptual artwork they accumulated. The second tale described a large group of paintings and other works by one famous artist quite generously donated with restrictions in 2022 to and accepted by the Metropolitan Museum of Art (“Met”) in New York City. The Met, of course, is one of the largest and most important institutions in the world; the enormity of its collection makes it impossible to fully display its collection, even in the huge building it occupies. The first story suggests that important art need not be squirreled away in the vaults of large collectors; the second suggests that it does. Both present instances where public access to art was simultaneously expanded and restricted. Together, they strongly suggest that private generosity, even of the loftiest sort, is unable to meet the needs for increased access to art.

Story #1: The Vogel Collection. In 2009, a remarkable documentary entitled Herb and Dorothy was released.30 Herb Vogel worked in a New York City post office; his wife, Dorothy Vogel, was employed by the Brooklyn Public Library. Over a period of forty-five years, they lived on Dorothy’s salary and spent Herb’s salary on art. They couldn’t house large pieces in their small apartment. Nor could they afford expensive works. But they had a good eye for up-and-coming talent. They managed to house what developed into a large collection in their small, rent-controlled apartment on the east side of Manhattan. The Vogels became well-known visitors at New York gallery openings and, over time, at artists’ studios, often buying drawings, prints, collages, and paintings by new, unknown, or emerging artists. By the early 1990s their huge collection included “the work of Sol LeWitt, Donald Judd, Richard Tuttle, Robert Mangold, Lynda Benglis and dozens of other artists who would come to represent the crème de la crème of Minimalist and Conceptual art.”31 They typically didn’t buy well-known work; they bought “what they liked.”32

Their apartment became so crammed that they ran out of room for more works in closets, under beds and furniture, behind dressers, in stacked piles, or hanging on or leaning against walls. After much thought and discussions with a number of institutions, they decided to transfer the entire collection to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. They did so because of the institution’s importance to the nation, its lack of an admission fee, and a policy of not selling their works. They were paid for it, but only in a modest amount dramatically below the actual market value.33 The Vogels had no interest in selling the collection for the seven figures many said it would easily produce at auction. Rather, they wanted to “give back” their collection to the nation that had allowed them to live a full, if intentionally humble, life. The National Gallery arranged to carefully package the entire collection into appropriate acid-free art files, containers, and crates, and to load it onto five(!) large semi-trailer trucks for transport to the nation’s capital.

After the gallery curators unpacked, cataloged, and appropriately stored the works, they evaluated the massive assemblage and concluded that it was impractical for the museum to permanently house and manage, let alone display, the entire collection in the museum’s facilities. With the full agreement of Herb34 and Dorothy Vogel, a decision was made to send 2,500 works, in fifty groups of about fifty pieces each, to fifty museums, one in each state.35 The rest remained at the National Gallery. The recipient institutions agreed to display the works they received for a time after they arrived and if they ever transferred them, to do so only as a complete group. The generosity of Herb and Dorothy was a remarkable display of sensitivity to the cultural and educational need for art to be available to a large cross-section of people all across the country. The documentary film, along with its sequel on the distribution of the collection around the nation,36 presented a remarkable portrayal of this gentle, unassuming, beautiful couple.37 They participated in the process of selecting the places where their collection went, personally visited many of the institutions, and met with visitors at a number of opening receptions. Their willingness to distribute their collection so widely was profoundly important and moving beyond words.

Story #2: The Guston Collection. At the other end of the donative spectrum is the 2022 gift by Philip Guston’s daughter, Musa Guston Mayer, of a collection of two hundred and twenty pieces from her personal collection, all by her famous artist father, to the Met in New York City.38 This certainly was not the first major gift of art to the Met. The collection has largely been built by the generosity of wealthy collectors of art, including some with less than savory reputations.39 This gift, however, raised concerns rarely publicly voiced over the years. Roberta Smith, the well-known art critic of the New York Times, wrote a trenchant and critical article about the donation, pondering the wisdom of concentrating so much art created by one person, as well as so much art from many sources, in one institution:

How much is too much? It’s a question that consumers should ask themselves every time they shop, build or step onto a fuel-guzzling jet.

It is also a question that museums might raise before adding works of art to their collections. This does not seem to have happened when the Metropolitan Museum of Art decided to accept 220 works by the celebrated—and prolific—American painter Philip Guston (1913-1980) from the personal collection of his daughter, Musa Guston Mayer.

The gift came with a big bright bow: Mayer and her husband, Thomas, are also giving the museum $10 million to establish the Philip Guston Endowment Fund to support Guston scholarship, which will instantly make the museum the world’s center for Guston studies.40

The gift terms also required the Met to place at least twelve of the works on display at all times for the next fifty years, regardless of how that would crimp the museum’s ability to properly show a broad range of other twentieth and twenty-first century American artistic styles in the limited amount of space devoted to recent time periods in their sprawling complex of galleries.41 The requirement that a small segment of the gift be displayed at all times is therefore a mixed blessing. On the one hand, it is wonderful that museum visitors will always be able to see some Guston works. On the other hand, it is not clear that using such a significant share of wall space for one artist’s work allows for the fair management of the museum’s modern collection. The Vogel gift was also a mixed blessing. The broad distribution of the works was an amazing decision. But the Vogel gift need not be on long term display either in whole or in part anywhere. The National Gallery is not obligated to show any of the collection to the public; nor are the fifty recipient museums around the country obligated to display their images after a first post-arrival exhibition.

The entire Met collection consists of over one and one-half million objects.42 Despite the huge size of the museum building, it can display only a tiny portion of the collection at any given point in time. Gallery space for fairly recent work is especially limited, though plans to expand the areas devoted to such work are afoot.43 May, Roberta Smith asks, such an institution responsibly accept such a huge number of items by one artist, regardless of how important that creative soul may be? In the absence of the presentation of a significant Guston retrospective exhibition at some point in the future, the bulk of the donation will remain hidden away all the time. In addition, Smith noted:

Accepting so many free Guston paintings flies in the face of the challenge that many museums face right now to redefine their missions in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement. Practically, and symbolically, it takes up too much of the oxygen in the room. To broaden their collections and audiences, museums should be seeking to avoid, not reinforce, the so-called master narrative that has largely excluded the achievements of women and artists of color.

This is also a period when museums are seen as overstocked treasure houses. Careful consideration should be given to how many artworks museums assume responsibility for. It would seem the last thing the Met needs is an enormous monument to an exemplar of America’s most famous art movement.44

These two stories display a small part of the depth of issues frustrating efforts to make art widely visible. The Vogel collection’s distribution was designed to spread the wealth among many institutions, including an array of “minor” collections in locations lacking notable museums, while not requiring that the pieces be publicly displayed on a regular basis. Indeed, the National Gallery of Art retained over 1,500 items from the collection. It is impossible for the museum to display that number of pieces simultaneously. They have neither the inclination nor the space. The museum simply has an informal policy to always have a few of the pieces from the collection on public view.45 Similarly, the addition of a large number of Guston works, some of which must always be on view, to the already massive hoard of art owned by an organization incapable of fully housing, let alone simultaneously displaying, a significant segment of its now extant collection, makes it virtually impossible for all of the Guston works to be shown simultaneously, either at the museum or elsewhere.46 Though, as these two stories suggest, some of the display issues involve practical limitations on the ability of institutions to regularly display the entire donated collections, other very important constraints also operate. That exploration follows.

C. Legal and Statutory Constraints

Taking the need for widespread public visibility of art seriously is also significantly constrained by the present structure of American law and the nation’s long history of art collecting. Despite the need to support the arts and to generate widespread access to the beauty, disturbance, reorientation, stimulation, intensity, and controversy it generates, deeply embedded cultural structures and misdirected economic incentives hide too much art from public view. Neither extant intellectual nor personal property laws provide any obvious clues about what, if anything, should be done to enhance the public’s ability to see art and to limit the scope of art caching. The problems are accentuated by the terms of copyright law that are thought to make it virtually impossible for artists to regain control over display of works after they leave their studios and fall into the hands of purchasers and successor owners. While both copyright and property law give artists and copyright holders a significant degree of control over decisions to display works in their possession prior to transfer,47 it does not explicitly provide them with authority to compel others owning their works to make them available for viewing, whether it be by a small group or by the general public. Finding pathways for compelling art owners—whether private or public—to bring works they own into public view is the central goal of this article.

The statute appears to provide on its face that copyright in a work of art remains with its artist and the artist’s successors in interest for the copyright term, which is typically life of the artist plus seventy years,48 unless the copyright is specifically transferred in writing.49 To effectuate the authority of copyright owners over display of their creations, the act grants an “exclusive right” to a copyright owner “to display the copyrighted work publicly.”50 Personal property rights in art held by artists prior to disposition also give them physical control over private and public display.

But those apparently large grants of authority are undermined by two critical statutory exceptions to the artist’s control over public access. First, the act provides that “the owner of a particular copy”51 of an art object “is entitled, without the authority of the copyright owner, to display that copy publicly … to viewers present at the place where the copy is located.”52 In addition, this provision of the copyright code, when read together with the personal property rights of art owners, is generally thought to allow the non-artist owner of a work control over loaning a work for exhibition, holding a work in a non-public way, or storing it in a location of the owner’s choosing. In all of these settings, the property owner effectively may determine the place where the work “is located.”

Second, the statute provides that “the owner of a particular copy … or any person authorized by such owner, is entitled, without the authority of the copyright owner, to sell or otherwise dispose of the possession of that copy.”53 While this provision does not deal specifically with display rights, it does allow an owner to transfer an artwork to anyone without regard to the desires of the artist, the successor copyright owner, or the intentions of the new owner to display or not to display the work. Given the statutory language, there is no apparent way for the copyright holder to object if a work is transferred to a party unlikely to ever display it. These results, it is thought, take precedence over the exclusive public display rights held by the copyright owner. And once a copyright finally expires, there are no statutory or other limitations on the ability of the possessor of a work of art to decide where and when to display it.54

Finally, the copyright statute itself understandably, though perhaps perversely, places significant limitations on the ability of non-copyright owners holding works still protected by the statute to actually display them online. The copyright statute’s definition of “display” includes online views.55 A number of important museums, including the Met, have recently created continually enlarging web displays of significant portions of their collections.56 But these changes are limited both by the willingness of museums to develop extensive online systems and their inability to place works still protected by copyright online without permission from the artist or the successor copyright holder. Though museums have the right to physically display all the works in their collections on their institutional walls at the place where they are located, including works in copyright, they need the permission of copyright holders to make digital copies of such works and display them online.57

origins of this rule are perfectly understandable. Allowing widespread display of all sorts of work is a common way for copyright holders trying to monetize their creativity. It is a form of advertising. Use of that marketing strategy, standard thinking goes, should be in the hands of the copyright holder. Breaking through this constraint to encourage more widespread online visibility of contemporary artistic works no longer held by the copyright owner is an important problem to resolve. In any case, museum internet presence today is typically limited to works no longer protected by copyright law. Therefore, none of the collections of the Met, the National Gallery of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Chicago Art Institute, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, or any other major museum are fully displayed online. In addition, an array of other American institutions has a small or non-existent online presence for any of their holdings.

As a result of the underlying legal structure, a museum, business, individual, or other entity owning a painting or sculpture, famous or not, is treated as having the right to decide whether to display it where it is located, even over the objections of the artist,58 or to not display it at all.59 Nor is it thought that a copyright owner may compel the property owner to display the work online. Works of art may therefore become perfect collectables—secure assets with hopefully increasing value—rather than cultural markers worthy of widespread viewing and admiration by the general public.60 They may be symbols of aesthetic understandings and admirable teaching vehicles, but there are often neither audiences granted the ability to appreciate such cultural attributes nor controls on where the property owner may keep it.61

Are there ways to break through the legal and cultural constraints? That is the question the rest of this article explores. What follows are observations about the various types of settings in which art may be hidden, suggestions about a variety of ideas to allow artists greater control over the display of their creations and about techniques for distributing collections across underserved geographic areas, as well as discussion of the practical limits to enhancing display.

II. Art ©aches

Art caches—collections in storage—are housed in different settings for a variety of reasons. The bulk of them are in either private collections or museum facilities. The works in private hands tend to be located in personal living and workspaces or in storage facilities. The art in personal spaces may be seen by those living or working there, or by visitors, but typically are closed off to the general public. The items in storage may well be in settings where no one sees the works for very long periods of time. Those places may be used either because the owners are out of room in their more standard personal spaces or because the owners see the works as investment assets62 rather than aesthetically alluring items appropriate for viewing by human eyes.63 In a small proportion of settings, wealthy collectors have opened their homes for public viewing or constructed or remodeled older buildings to house their collections and make them easily accessible to the general population. There are a number of examples of such facilities, including the Kreeger Museum in Washington, D.C.,64 the Rubell Museum sites in New York and Miami, the Margulies Collection at the Warehouse and other institutions in Miami, Florida,65 and a host of others across the nation and world.66 In such settings, personal collections take on the characteristics of a museum while often providing tax benefits to their owners.67 Stored works owned by museums and other institutions, whether privately or publicly owned, are most likely in hiding because the institutions lack the space to show them, the art is deemed unworthy of display in the present aesthetic milieu, the museum has a surfeit of works representing certain artists, eras, or movements, or the fragility of the pieces requires that they be kept in special locations for preservation or conservation. Many museums and libraries have special systems set up that allow for a diverse array of researchers to study works in storage.68

The varying causes for the existence of art caches, along with the extant legal limitations, make analysis of the hoarding issues and the potential cures for any problems difficult and complex to explore. Questions of privacy, property rights, and investment goals dominate standard attitudes about the personal hoards. Interests of the public in viewing the works, if any, are difficult to legally support and financially sustain in the present milieu.69 Attempts to control museum collections also involve property interests, as well as the ethics and rules of collecting and deaccessioning, the purposes for the existence of art collecting institutions, the educational missions of museums, the impact of public funding, and the public’s desires to experience the ability to see and think about the works in the collections. Put together with the quite different concerns of private art owners, these museum problems add additional complications to the discussion. Even if limitations on the caching of artworks were to be imposed, how long should such limitations exist after the death of the artists, and who should have the ability to force art owners to make the works they own available for public viewing?

A. Museum Collections

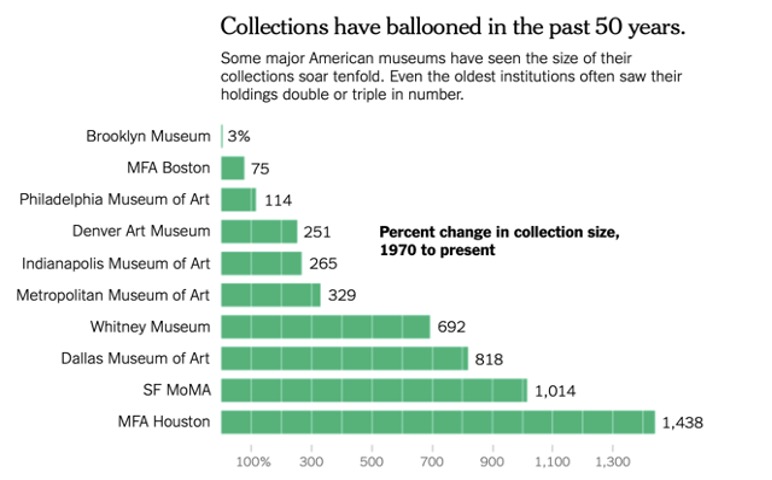

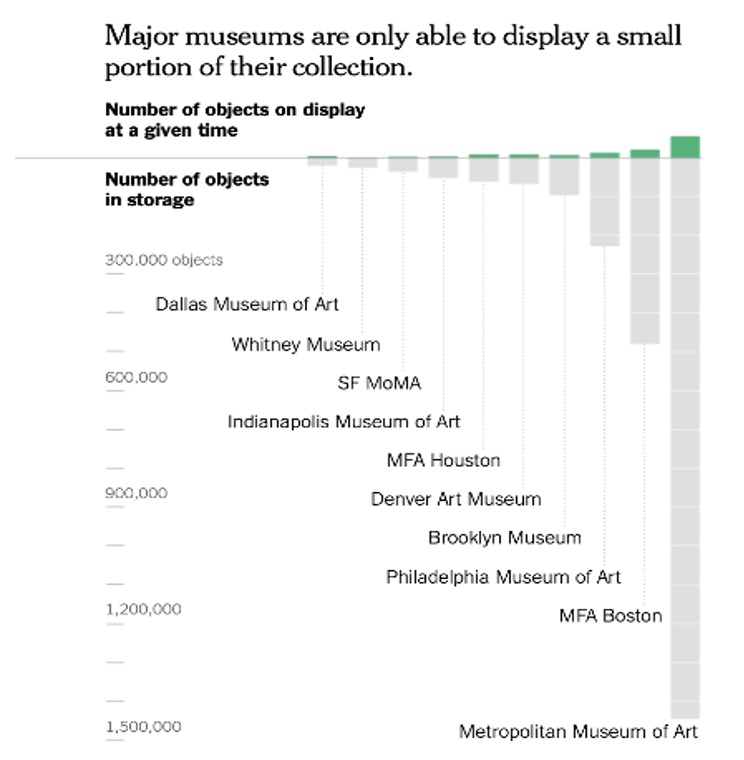

Museums own an enormous amount of art that rarely sees the light of day.70 Instincts to amass collections, typically thought to describe librarians, also are deeply embedded in the psyches of large institutions like the Met, as well as at some privately created museums.71 The limitations on such institutions wishing to deaccession art—psychic, normative, and legal—can seriously constrain their ability to reduce the size of their rarely seen or less interesting holdings by transferring them to museums with available display space.72 Robin Pogrebin vividly described the issues in a recent article in the New York Times.73 She used two charts displayed below to demonstrate the enormous scale of the problems. The first shows the dramatic growth in the size of some major collections, and the second shows the proportion of holdings that are publicly displayed at any given time by such important museums. While the numbers are staggering, don’t lose sight of the fact that almost all privately held art is not available for public viewing. The number of privately held pieces is probably larger than the volume of stored museum works.74 And it is also true that a significant number of privately held works are just as important exemplars of artistic quality as those in major museum collections.

Pogrebin went on to note:

It doesn’t benefit anyone when there are thousands, if not millions, of works of art that are languishing in storage,” said Glenn D. Lowry, the director of the Museum of Modern Art. “There is a huge capital cost that has a drag on operations. But more importantly, we would be far better off allowing others to have those works of art who might enjoy them.75

The Museum of Modern Art regularly culls its collection and in 2017 sold off a major Léger to the Houston Art Museum. Yet, it too is in the midst of another costly renovation (price tag $400 million) to be able to exhibit more of its ever-growing collection.76

Part of the problem is that acquiring new things is far easier, and more glamorous, than getting rid of old ones. Deaccessioning, the formal term for disposing of an art object, is a careful, cumbersome process, requiring several levels of curatorial, administrative and board approval. Museum directors who try to clean out their basements often confront restrictive donor agreements and industry guidelines that treat collections as public trusts.

There also are unforeseen risks in relying on large collecting institutions beyond the sheer mass of items they hold. The unwieldy nature of massive collections generates specific risks absent in many other collection settings. Keeping track of the collections, maintaining systems for finding proverbial needles in haystacks when access is desired, ensuring vigilance over the condition and integrity of the works over time, and guaranteeing security becomes more difficult and expensive as collections grow in size. That was recently made quite clear when a curator managed to remove 2,000 items over the last decade from storage facilities at the famed British Museum.77 Size may not guarantee greater safety and security than private owners and smaller museums. Dispersion of collections and size reduction may lessen the likelihood of similarly huge thefts from occurring in the future.

1. Limitations on Dispersal and Viewing Museum Collections

The Met and most other museums may be constrained in their desire to deaccession works for display in different settings not only by the power of their instinct to amass collections, but also by five different sets of rules—limitations established by the institution’s founding documents, limiting terms contained in documents for gifts accepted by the institution,78 legal rules surrounding operation of the legal form under which the institution operates, state statutory obligations on non-profit organizations, and norms established by national organizations with long histories of setting guidelines for museum operations.79

The Met was created as a non-profit corporation under a state charter adopted by the New York General Assembly in 1870 “for the purpose of establishing and maintaining … a Museum and library of art, of encouraging and developing the study of the fine arts, and the application of arts to manufactures and practical life, of advancing the general knowledge of kindred subjects, and, to that end, of furnishing popular instruction and recreation.”80 The museum’s ownership structure is unusual; the building and the land it is on in Central Park are publicly owned while the collection is held by the museum. The institution’s obligations flow not to the members of its governing board but to the general public; its duties are to benefit the public not itself. Use of the term “library” in the 1870 legislation connotes the development of a substantial array of works, perhaps inevitably given the wealth of some city residents, leading to an enormous growth in its holdings. Nonetheless, in recent times the Met has regularly culled its collection.81 Simply as a matter of space, it has become impractical to retain all of its pieces. Similarly, Charles L. Venable, the director of the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, recently cancelled a planned storage space expansion by taking the very unusual step of removing from the collection works that received a grade of D or below when rated by the staff as to whether their retention would be a “drain on resources.”82

While the founding charter of the Met states very broad purposes and goals for the museum, norms at other institutions may be much more constraining. That is vividly demonstrated by a recently filed legal proceeding challenging the desire of Valparaiso University’s Brauer Museum of Art in Indiana to sell works, including three of its most valuable pieces by Georgia O’Keefe, Frederic E. Church, and Childe Hassam, to raise money for improvement of the university’s first year student dormitories.83 The dispute arose due to concerns over spending the money raised on non-art related undertakings as well as the deed of gift for the 400 pieces originally used to establish the museum required that it would “display a representative selection of the works of said Junius R. Sloan in a suitable place not less frequently than once in each year.”84 The museum, however, claimed that nothing in the donative documents established a deaccessioning policy and that the university was free to dispose of the works. The university’s faculty voted to oppose the planned sale, in part because members of the art faculty regularly used the collection in their classes,85 a practice strongly supported by the cultural need for creativity to be easily seen by the general population.86

While the Valparaiso dispute was recently dismissed,87 other controversies leave a mixed picture about how severe the legal and cultural limitations are on deaccessioning, as well as on public visibility of art. For example, a 2017 decision by the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, Massachusetts to sell assets, including two Norman Rockwell paintings, because of the institution’s dire financial condition, caused a significant uproar in the local area and led to litigation in the New York courts. The dispute’s outcome—sale of the two works88—demonstrated that deaccessioning may cause a decrease rather than an increase in public access to art in the absence of efforts by the selling museum to oversee the selection of the ultimate buyer. One of the two works found its way to another museum while the second, auctioned at Sotheby’s, fell into unknown hands.89

The sales by the Berkshire Museum were enmeshed not only in local and legal controversy, but also in public opposition from major institutions setting standards for museum operations. Both the Association of Art Museum Directors (“AAMD”) and the American Alliance of Museums strongly criticized the sales of the Rockwells and other works.90 The AAMD imposed sanctions on the museum by requesting that other museums “refrain from lending works to the Berkshire Museum or collaborating with it on exhibitions.”91 Though the AAMD rules were modified in 2022, the museum still would have violated the new norms. Professional Practice Rule 2.5 provides that “[f]unds received from the disposal of a deaccessioned work of art including any earnings and appreciation thereon, may be used only for the acquisition of works of art in a manner consistent with the museum’s policy on the use of restricted acquisition funds or for direct care of works of art.”92 Norms like this simply enhance the collector instincts of museums without much consideration for the need to display works to the public or for the difficulties of operating and supporting institutions unable to manage and maintain their collections.93

2. Techniques for Opening Museum Collections

Given the array of limitations on museum behavior, it is difficult to imagine steps institutions could take that would significantly alter the present situation. Most being tried have a limited impact. Enhanced online systems and open storage facilities, for example, have provided limited steps toward wider access. Displays of online images94 certainly cannot substitute for onsite views. They do not provide viewers with comprehensive impressions of the works. Even if magnification of segments of an online object are made available, the perspective gained by onsite viewing of the entire object cannot possibly be duplicated. Large compositions, in particular, simply “disappear” when viewed on standard desktop technology outside of a museum. Nonetheless, online displays certainly are much better than failing to display works in any format; and for copyright purposes they are deemed to be public displays.

Another fascinating possibility for online viewing has recently appeared with the creation of online systems allowing users to scan gallery walls, including an ability to focus in on works hung there.95 Though it does not expand the number of works publicly displayed for onsite, in person viewing, it does remove common limitations on access by avoiding entrance fees and eliminating transportation difficulties and costs. Though these systems may not always display images of works still copyrighted, they easily could. Would this violate a copyright owner’s right to control the making and distribution of copies of their works, or would it fall under the right of museums to publicly display works in the place where they are located? Public display, after all, includes the right to use online technology, but are the images produced at the place where the work is located? Similar problems would arise if a private owner or museum created an online system displaying apartment rooms or galleries with art on the walls. I suspect the answer is that such systems create copying problems under the statute, especially if the technology allows users to enlarge the images on screen. They both create copies of works and facilitate the making of images by users by simple copying or screen capture techniques.96 But the answer to the statutory conundrum—especially questions about location—is not obvious. Nor is it clear if such display systems would be fair use.97 No one, of course, anticipated such systems when the statutory display provisions were originally drafted.

Another solution is now provided by a few institutions that have “open-view” storage areas allowing visitors to browse among works stored in places with sliding or other accessible viewing systems.98 These facilities allow both for appropriate compact storage and for actual rather than online viewing of works not on display in regular galleries. Though lacking in the provision to museum audiences of many-sided views of a work from varying distances or perspectives, these facilities do allow visitors to capture a reasonably direct sense of a work’s impact. A few institutions also have arranged surprisingly wonderful exhibitions organized by members of their staffs specifically designed to bring works out of storage for public viewing.99 And of course, the large number of works in private collections are completely out of public view, either in person or online. As noted in the opening pages of this article, however, some large private collectors have made significant efforts to put their art troves in publicly accessible museums100 or online.101

But perhaps the most intriguing system for broadening public access to art collections operates in France. The structure of the collection and display systems in France has allowed for an entirely different approach to making museum art more visible to the general population. It relies on the fact that a very large portion of the major works on French soil are part of the national collection. Major steps to broaden public access across the nation to the enormous number of government-owned works have been taken in recent decades. Rather than being retained in Paris, many important works have been distributed to a significant number of institutions scattered across the country. Creating this broad array of sites was consciously planned to broaden public access to works of art.102 Even mobile displays housed in large trucks roam around the country.103 Among the stated goals of establishing the museum network was “to ensure the reception of the widest possible audience, to develop its attendance, to promote knowledge of their collections, to design and implement educational and dissemination actions aimed at ensuring equal access to culture for all.”104 This policy, strongly analogous to the distribution of the Vogel collection described near the outset of this article,105 suggests one way of thinking about how to remedy some of the difficulties of using large stand-alone institutions as the backbone for public art viewing in a nation as large and diverse as the United States.

The United States owns an important—but relatively small—national art collection, which is currently housed in various Smithsonian Buildings, mostly in Washington, D.C.106 Adopting a system here like the one in France would require a noticeable change in attitudes about making art located in our major private and publicly owned museums outside the Smithsonian umbrella more easily accessible. Since most major holdings are not in government hands, Congress would have to enact a system of federal encouragement and spending to create branches of large museums and arrange traveling exhibitions. Large construction and building maintenance grants should be given to entice institutions to display parts of their collections in scattered locations under the same sort of rules proposed above and in the proposed statutory amendment described below for privately held works.107 Legislation could also be passed to override deaccession rules by allowing for the sale or exchange of works to an array of museums that promise to display the works on a regular basis. Such locational shifts would emulate the way in which public funds benefited the public during the years the FAP was extant. Of course, Congress could also simply compel museums to show all items in their collections at least once a decade, or some other reasonable period of time. In short, there are ways that the nation can emulate French policy even though most museums are not owned by the national government and large important collections are privately held.

B. Private Collector Art ©ache Problems and Possible Solutions

Are there ways to enhance public viewing of art in privately held collections located in the non-public living or work places, in privately created museums, or in storage? Given the typical American predilection for allowing owners of tangible property to do as they wish with their assets, any challenge to the “right” of art collectors to keep their collections private will inevitably run into stiff cultural headwinds. An art owner’s property right to control access to and possession of their work and the copyright statute’s provision granting control over public display of an art object where it is located to the owner of the physical asset, rather than to the copyright owner, are typically thought to create substantial barriers to altering traditional rules.

That view is short sighted, however. There are some issues worth exploring in this arena. At least three paths exist to increase the frequency of public access to privately owned works, whether hung in personal spaces or placed in storage. First, the statutory exception to a copyright owner’s display right giving a private property owner the privilege to publicly show art where it is located should not continue to operate when the owner declines to display it to anyone, let alone to the public. A new look at the statutory language is a first step toward increasing public access to works hung in private locations visible only to a few or indefinitely stored away out of sight. The standard construction of the statute’s grant of authority to successor owners of art, I suggest, is vastly overstated. Second, private contracts or other legal systems of constraint on buyers signed at the time of first sale of a work may be used to force art owners to make works they own available for display, either to limited or to significant numbers of people. Third, the best solution to the dilemmas posed by privately owned hidden art is to amend the display provisions of copyright law to grant artists more control over what happens to their work after it leaves their studios and to grant the government the right to compel some art no longer protected by copyright to be publicly displayed.

1. Reconsidering the Statutory Display Provisions

As already noted, artists108 are thought not to have a right to compel private owners of the works in which the artists hold copyright to make them available for viewing by members of the general public. The combined abilities of non-artist owners to exercise their property-based power to decide about display of their personal assets and their statutory authority to publicly display work where it is normally located are typically believed to allow removal of art from public view at the whim of the owner. But surprisingly, the wording of the statute is quite open to a more limited interpretation than typically thought. That, together with the enormous public benefit gained when the access to art is widely available, suggests that there are ways to reconstruct the presumed meanings of the statutory rules of public display.

The code states that an owner of a physical item of art “is entitled, without the authority of the copyright owner, to display that copy publicly … to viewers present at the place where the copy is located.”109 It does not say that the owner has the right to “control all places where a work is displayed,” or to “have unlimited control over whether to display or not to display a work” or to “exercise complete dominion and control over when and where a work” is displayed or to only display it in ways that are not “public.” There certainly are “holes” left in the language about what happens when the owner of a work elects to display it rarely or not at all in either a private or a public location. While the statute may be construed to include all the negative as well as the positive meanings of the statutory phrase granting an owner the right to publicly display a work where it is “located,” that result is not mandatory; it contradicts the apparent meaning of its language and undermines the public purposes for displaying art.

The owner’s statutory display authority is framed as an exception to the general rule granting copyright holders the exclusive authority to exercise dominion over public display of works in which they hold copyrights. That exclusive authority of the copyright owner should be construed broadly in light of the public benefits bestowed on society by displaying rather than hiding creative works. In a setting like this where the statutory meaning is difficult to precisely discern, the ambiguity should be resolved in favor of copyright owners retaining some authority over when and where their art is publicly displayed.110

The strong public policy reasons for publicly displaying art as often as possible lead naturally to denying a non-copyright holding owner of an artwork an unfettered right to not display it publicly. Such unbounded power vested in the owner of an art object is an unwarranted and broad expansion of the narrowly drawn statutory exception granted to an art owner to publicly display a work where it is located.

The reality that artists’ typically unspoken intentions routinely include a desire that their creativity be seen, and an expectation that those perusing art gain ineffable public benefits from doing so,111 supports the conclusion that the statutory authority of a non-copyright holding owner of a work should be construed to include a right to control public display of art where it is located, but not an unbounded right to refuse to publicly display art anywhere for long periods of time. State personal property rules should not be allowed to override this conclusion. It would create a significant conflict in purpose between the goals and values of federal and state law that would force a conclusion that state law should be preempted by the Supremacy Clause.112 The existence of a copyright holder’s exclusive right to control public display should govern in all settings not explicitly covered by exceptions granted to the physical owners of art.113 The refusal of an art owner to display a work frustrates the benefits bestowed on the public when art is publicly visible; the owner’s display interest should yield when an artist or successor copyright owner reasonably demands that the work be publicly shown in some fashion under the grant of an exclusive right to do so under 17 U.S.C § 106(5).114

Given the existing terms of the copyright statute and the lack of express provisions for granting a copyright owner control over public display when the owner of a work keeps it out of view for an unreasonably long period of time,115 the courts must fashion some fair and reasonable way of organizing the display rights of artists and their successor copyright owners. That balance is best struck by crafting several control mechanisms. First, if an artist’s work is initially transferred by a gallery or other third party, the transfer agent should be judicially required to inform the artist of the transferee’s contact information and the planned location for the work on consummation of the sale. This is a minor imposition since the agent or gallery would typically be paying the artist upon transfer of the work. If and when the artist wishes to follow up to see if the work has been publicly displayed, this information will allow for tracing inquiries to begin. Included in this legal structure should be a requirement that each owner of a work of art divulge to the artist or successor copyright owner the identity of a transferee of a work if it is sold or otherwise disposed of, as well as the planned location for the work. Second, the artist or copyright holder should be allowed to demand the right to publicly show long hidden works for a reasonable period of time.116 The cost of display should be the responsibility of the copyright holder, just as it was before the work was transferred.117 The right being enforced, after all, belongs to the copyright holder who would have managed displays prior to the transfer. Third, if the property rights holder voluntarily places the work on public display for at least ninety days once every three years (for example), the copyright holder might be barred from seeking further visibility unless the work fails to reappear for another significant period of time. Fourth, the copyright holder should be granted the right to demand that a high-resolution digital image of a work be provided to the copyright holder if the owner of the physical copy declines to place the work online upon request.118

2. Private Constraints on Display of Art

The complexity of the potential interplay between statutory display rights held by copyright owners and those held by owners of objects suggests that the vagaries of the statute will be challenging for courts alone to resolve. The problems could be reduced or eliminated either by routine use of coherent private legal techniques or by congressional reforms. Past efforts to control display rights privately have largely, though certainly not completely, failed to develop into routine practices. That tale is briefly told here. Suggestions for legislative reforms follow in a later section of this article.

Several types of private arrangements have either been proposed or used—selling or transferring art using contracts “running with the art,” limited liability corporations (“LLCs”), non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”), and conceptual art. The best-known effort to use contracts “running with the art” arose from artist protest demonstrations at the Museum of Modern Art and other locations in the late 1960s and the related creation and widespread distribution of The Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement119 published in 1971 by Seth Siegelaub and Bob Projansky. Sale via limited liability corporations or NFTs are more recently minted ideas.120 Conceptual art became a lively and well-known transfer vehicle in the late 1960s and 1970s and is still used. But none of these techniques has ever become standard practice widely used by either artists or dealers.121 Each of these arrangements and their problems are surveyed below.

i. Contracts Running with the Art

The Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement (“Artist’s Contract”) makes use of legal theories virtually identical to those widely used in creating servitudes running with the land. The central concept generally accepted in real property-based servitude law is fairly simple. The owner of property signs a contract as part of the process of making a conveyance with the clearly stated intention to create a limitation on the land binding both present purchasers and future successors.122 Since the constraint is routinely inserted in deeds or other instruments used and recorded when interests in land are transferred, the successors in interest always123 have actual or constructive notice of the restraint in their chain of title and therefore must take its binding impact into account when deciding to invest in the asset. The oft stated legal rule says simply that a party owning land on notice of restrictive terms related to the property itself is bound by them. The device is widely used to craft rules for the operation of condominiums and other “common interest communities.”124 The Artist’s Contract uses the same idea to bind purchasers of art to constraints on the transfer, display, and handling, as well as on the care and protection of a work by requiring that successors be placed on notice of the terms of the contract.125

The introduction to the Artist’s Contract summarizes the basic provisions of the arrangement. The portions I italicized are obviously the most relevant to this article.

The Agreement is designed to give the artist:

- 15% of any increase in the value of each work each time it is transferred in the future.

- item a record of who owns each work at any given time.

- the right to be notified when the work is to be exhibited, so the artist can advise upon or … veto the proposed exhibition of his/her work.

- the right to borrow the work for exhibition for 2 months every five (5) years (at no cost to the owner).

- the right to be consulted if repairs become necessary.

- half of any rental income paid to the owner for the use of the work at exhibitions, if there ever is any.

- all reproduction rights in the work.

The economic benefits would accrue to the artist for life, plus the life of a surviving spouse (if any) plus 21 years, so as to benefit the artist’s children while they are growing up. The artist would maintain aesthetic control only for his/her lifetime.126

The agreement has not been frequently used.127 The reasons, I think, are easy to fathom. Most dealers and purchasers of art, in both the high and low ends of the market, do not find the Artist’s Contract to be in their best interests. Given the present legal structures granting largely untrammeled authority to art buyers to control the use and disposition of works they buy, the incentives do not run in a favorable direction for artists. In addition, it is hard for most artists to sell their work. If they want to sell, they have to be willing to abide by the buyer’s preferred terms. It would be uncommon, though far from a complete rarity, to find art buyers firmly committed to making the works they purchase regularly available for public viewing and to sharing with the artist any growth in value of the art surfacing in later sales.128 Conceptual artist Hans Haacke is one quite notable exception.129 Those artists or art owners firmly committed to using the Artist’s Contract may often find it difficult to sell their work without price discounts or even to sell their work at all. The artists most likely to successfully convince buyers to adopt the Artist’s Contract or something like it are those already well known with a solid coterie of people and institutions eager to purchase their work or those newly arrived on the scene with multiple gallerists eager to sell their work or buyers wanting to get on board.

ii. Limited Liability Corporations and Non-Fungible Tokens

Similar incentive problems to those that stymy use of running contracts arise in the use of LLCs and NFTs. Though both may be used to craft constraints on art similar to those embedded in the Artist’s Contract, they probably run into similar market constraints.130 An artist using an LLC may create a legal entity in which the artist owns the copyright and a significant share of the LLC, such as 20%, in a painting held by the business organization. The remaining interest in the LLC, but not the copyright, would be sold to a collector. The relationship between the artist and the collector are spelled out in the entity’s operating agreement and could include any of the terms in the Artist’s Contract or others desired by the parties. Provision could be made for rights of display, sharing of proceeds obtained from copyright interests such as poster making, public exhibition, or sale of the work, limiting sale of the work by requiring permission from both the artist and the collector, and guaranteeing that any new member of the LLC would be bound by the same restraints as the original investor. Interests in the LLC could be spread among a larger group than just the artist and a single collector, though the larger the group the more cumbersome management and transfer of interests would become. Sales of interests in an LLC are typically controlled by the terms of the operating agreement.131 A sale of some shares or a complete sale of all the shares of the LLC owning the painting would result in payment of the appropriate membership share of the price to the artist.

Using NFTs is more technologically and theoretically complex. NFTs themselves are best characterized as ownership “certificates” for a share of a work of art, often evidenced by an image of a small segment or thumbnail of a painting not accessible by other owners of NFTs in the work. The owner of an NFT thumbnail typically also may link to an image of the complete painting online. The owner’s NFT certificate is accessible on a blockchain to the owner holding the coded key. And that interest typically is transferable by payment with crypto currency which can be “cashed out” to dollars on a dedicated monetary exchange. As with LLCs, the artist will own a significant share of the NFTs, such as again 20%, as well as the copyright in the actual work. Control over display of the work may easily be maintained by the artist if the party holding the actual work is either the artist or the agent of the artist. The marketing problems are related both to potential reluctance of traditional collectors to yield to such an ownership pattern and to the now well-known issues presently impeding the use of block chain technology and crypto currency transactions.132

iii. Conceptual Art

The most successful and widely used system for allowing artists to control display and marketing of their work is conceptual art, though economic limitations have also hindered its widespread adoption. It is built on the notion that the most critical aspects of art are ideational, not tangible. In a brief essay, Sol LeWitt was among the first to describe the nature of such endeavors:

In conceptual art the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work. When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art.133

LeWitt, along with other famous artists such as Donald Judd and Dan Flavin, are among a number of widely recognized practitioners of this genre. To these artists, the “work” was manifested by documents of title rather than in objects, by written indicia of artistic ideas rather than tangible things. As I described the notion in a previous article:

Whether the installed work was a wall drawing by LeWitt, a construction by Donald Judd, or a lighting work by Dan Flavin, the pieces were often described by the artists as temporary, movable, or destructible after their installation. Such projects were distinctly different from routine art sales by galleries or auction houses. Rather than obtaining a painting or sculpture, a buyer obtained only the right to seek its creation and installation. It was the creative plan that was the artistic product, not an extant creative work.134

Rather than an extant artwork, buyers receive a certificate of ownership or authenticity, as well as a document with instructions on how to install the work.135 These items typically are written, expressive, original works of authorship copyrightable by the artist. They overcome the bar on copyrighting ideas. That means that permission of the artist or other copyright owner controlling the exclusive right of display typically is required for each installation. While only those holding a certificate of authenticity136 may seek to install the work, they do not have total freedom of action. That is because most installations are derivative works137 of the art as described in the copyrightable certificate of ownership and the instruction set and permission of a copyright holder is required before a derivative work may be made. Because of the complexity of most installations, those doing the work may also hold a copyright interest in the derivative work as derivative work authors.138 As a result, the copyright owner has control over the location of the installation and often oversees the selection of the installers.139 Many installations are also temporary and somewhat different project to project. Varying the spaces where works are installed may have an impact on the size and shape of the work. Because of the complexity of the ownership pattern—original author, installer, and certificate owner, complexity may arise if there is a desire to destroy the work or sell it without the permission of a range of people.140

Many conceptual artists assemble or arrange for the creation of initial installations. That is the way their reputations are established. One of the most important exhibitions of conceptual art now on display is a huge array of Sol LeWitt wall drawings installed with LeWitt’s oversight in Building #7 at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art. A small segment of the show is displayed below.141

The use of certificates of ownership and instruction sets allowed LeWitt and others to continue to control many aspects of their work over time—a goal common to the less frequently used Artist’s Contract, LLCs, and NFTs. It also may allow for the sale of a physical object created by artists for permanent rather than temporary exhibit, as well as for additional versions of each work to be made and sold later. The ownership certificate could provide for distribution of the price obtained in such sales. It is extremely flexible and allows art buyers to gain a significant amount of control over the works they purchase by use of conceptual art documents, especially if only one object at a time is allowed. This flexibility for both the artist and the buyer makes it understandable that conceptual art projects are more common than other limited sales techniques. Even here, however, use has been limited. The ongoing interplay between an artist or an artist’s successors in interest and art buyers over installation locations and creation may deter many from making purchases. And, of course, works crafted as “permanent,” unique items don’t fit within the parameters of the typical theoretical foundations surrounding conceptual art.

In sum, the hopes of some that private law mechanisms might enlarge the now limited ability of artists to control the future lives of their art after it is transferred have largely been frustrated by a combination of real and perceived statutory limitations and forces that limit the ability of creative souls to enter negotiations on a level playing field. This is, therefore, an area ripe for legislative intervention.

C. Legislative Reforms

Embedding the various reform proposals in this article into legislation is clearly the best way to handle the situation. Three sets of changes are required—one to the copyright statute display provisions covering the rights of copyright holders to demand displays of their works, another allowing for greater museum flexibility and compelling display of more of their collections, and a third establishing a program for constructing and organizing art displays nationally, especially in presently underserved areas. This section will propose legislative language only for the first two. The third set of legislative enactments will require a much more involved legislative proposal drafted after consultation with the institutions most seriously affected by the program and the federal agencies most directly involved in creative projects.

1. Amending 17 U.S.C. § 109(c)

The terms embedded in 17 U.S.C. § 109(c) granting control over public display rights to non-artist owners of artworks certainly need to be changed. It is important to reemphasize that the definition of public performance or display in 17 U.S.C. § 101 includes both “a place open to the public or at any place where a substantial number of persons outside of a normal circle of a family and its social acquaintances is gathered,” as well as a communication “by means of any device or process whether the members of the public capable of receiving the performance or display receive it in the same place or in separate places and the same time or at different times.” The first part of the definition encompasses physical locations where the work on display is visible to those present, while the second part includes the provision of online viewing. The first display method is more culturally meaningful and important, but also more difficult to guarantee because of the enormous size of some collections. The statutory amendments must take the difference into account. Requiring broader online dissemination of works rather than physical display in a venue might best meet the needs of all parties. And given the importance of public access suggested here, the display rights provided for in any statutory reforms, like traditional moral right provisions, should not be transferable or waivable.142

There is one other issue that should be taken into account. There is a significant difference in the likelihood of public display between unique artistic works—such as paintings, collages, easily reassembled installations, and sculptures—and works often produced in editions of a number of copies, such as prints and photographs. The initial copyright holders of prints and photographs may sell only part of any given series of copies or retain the ability to make additional ones.143 Even if the artist destroys the plate for a print or the original negative or computer image of a photograph, an argument may be made that additional, strong display powers in the hands of the artists are not as necessary as with unique items, except for prints and like objects made in small numbers. The larger the number of copies made, the greater the likelihood that at least one version will be on public display at any given moment in time.144

For discussion purposes, I suggest the following redraft (changes italicized) of 17 U.S.C. § 109(c) designed to deal with the problems of both privately and institutionally owned art still protected by copyright:

(c) Notwithstanding the provisions of section 106(5), the non-copyright holding owner of a particular copy lawfully made under this title, or any person authorized by such owner, is entitled, without the authority of the copyright owner, to display that copy publicly,145 either directly or by the projection of no more than one image at a time, to viewers present at the place where the copy is located. With regard to a particular copy of a work of visual art146 originally created in fewer than twenty147 rather than two-hundred copies:

(1) Any party transferring ownership of such a copy on behalf of the original creator or owner of the copy shall inform the copyright owner of the contact information, including, location, address, phone number(s), and email addresses of the original transferee.

(2) Any non-copyright holding owner148 of such a copy shall make every reasonable effort to inform the copyright owner of that copy of the contact information, including, location, address, phone number(s), and email addresses of the non-copyright owner and all changes in such information that may occur over time.

(3) If the non-copyright owner of such a work transfers the copy, the owner must make every reasonable effort to notify the copyright owner of the terms of the transfer, including but not limited to the name and full contact information of the transferee.149

(4) The copyright owner of the work retains the authority to display the copy of the work in a place open to the public for a period of at least sixty days if such copy has not been publicly displayed by any non-copyright holding owner for a period of at least ninety days during the prior three years.

(5) The right of public display in a place open to the public held by the copyright owner under subsection (4) is subject to the following limitations:

(A) All reasonable costs associated with arranging for display of the copy in a place open to the public shall be borne by the copyright owner.

(B) Such reasonable costs include insurance, packaging, shipping, and arranging for a display venue.

(C) If the copyright owner elects not to pay the costs imposed under subsections (A) and (B), then the copyright owner may require the non-copyright holding owner of the copy to arrange to publicly transmit or to otherwise communicate or display the work to the public, by means of any device or process, whether the members of the public capable of receiving the performance or display receive it in the same place or in separate places and at the same time or at different times for a period of at least ninety days without payment of any funds from the copyright owner.

(6) The copyright owner retains the authority to publicly transmit or to otherwise communicate or display the work to the public, by means of any device or process, whether the members of the public capable of receiving the performance or display receive it in the same place or in separate places and at the same time or at different times for as long as the copyright owner desires.

(7) The rights held by a copyright owner under subsections (1)-(6) shall not be waivable or transferable.

(8) If the non-copyright holding owner of the work demonstrates that the exercise of any right under subsections (1)-(6) held by the copyright owner of the work would place the work under a risk of serious harm and no way exists to safeguard the work from such harm, then the owner of the work may retain possession of the work in a location that does not create a risk of serious harm to the work.

(9) This section applies to all United States works regardless of whether they are located in the United States or elsewhere.

2. Compelling Display of Items No Longer Protected by Copyright