By Aaron B. Rabinowitz*

A pdf version of this article may be downloaded here.

I. Introduction

A. Background

In the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2005 watershed decision in Booker v. United States,[1] federal judges now exercise newfound discretion in imposing sentences on criminal defendants. Before Booker, judges imposed sentences according to the sentence ranges set forth in the United States Sentencing Guidelines (the “Guidelines”),[2] with outside-Guidelines sentences being imposed in only a few rare cases.[3] Under the Guidelines, a judge would apply a cross-reference table that suggested a sentence range based on the severity of the offender’s actions and the offender’s own criminal history and then, absent any special circumstances, impose a sentence within that suggested range.[4]

The Booker decision, however, brought a significant change[5] in sentencing practice by rendering the Guidelines advisory only.[6] By making the Guidelines advisory only, Booker granted sentencing judges significant control over the magnitude of sentences,[7] as judges were no longer bound to sentence according to the ranges that the Guidelines suggested.

Coincident with the Booker-catalyzed changes in federal sentencing, society has seen a significant increase in intellectual property crimes – the number of defendants sentenced under the intellectual property sentencing guidelines grew steadily by an average of 6.8% per year from 1997 to 2007. This growth in intellectual property offenders was, however, 50% faster than the overall growth rate for the total number of offenders sentenced under the Guidelines during those years. Given that individuals and corporations derive great value from their own intellectual property, a full understanding of how judges impose sentences for intellectual property crimes is critical.[8]

To better understand the judiciary’s and society’s views of intellectual property offenses, and whether the sentences actually imposed for these offenses are consistent with these views, this article presents an empirical analysis of data obtained from the United States Sentencing Commission to identify trends in sentencing for intellectual property crimes. Because Booker was decided six years ago, the number of pre- and post-Booker cases is now large enough that one can now properly assess the impact of Booker on intellectual property sentencing. The data sets included 425,597 pre-Booker and 435,415 post-Booker cases. This article extracts from the empirical analysis a number of critical hypotheses concerning judges’ views of intellectual property crimes and of the Guidelines in general.

B. Overview of Findings

As described below in more detail, this article’s empirical analysis reveals that the Booker decision has affected sentences in intellectual property crimes in a significantly different way than the decision affected sentencing decisions for general and other comparable economic crimes. These findings include: (1) sentences imposed on intellectual property offenders deviate from the advisory Guidelines in two out of every three cases; (2) prosecutors seek and judges reduce sentences for intellectual property crimes more frequently than for other comparable crimes; and (3) following the Booker decision, judges reduce sentences for intellectual property crimes seven times more frequently than they did before Booker, the frequency of which far outstrips the rate at which judges reduce sentences for other comparable crimes.

The fact that two-thirds of intellectual property crime sentences are below the Guidelines sentencing range suggests that the Guidelines range is not in harmony with the sentences that prosecutors and judges deem appropriate for these crimes. Second, the fact that judges and prosecutors reduce sentences for intellectual property crimes more frequently than they do for crimes in general or for other comparable economic crimes suggests that judicial actors believe the Guidelines sentences for intellectual property crimes are too stringent.

This article also considers changes to the current sentencing process so as to align the process more closely with the way sentences are imposed in practice. Booker-empowered judges very frequently use their discretion to impose sentences on intellectual property crimes that are outside the Guidelines. This suggests that the Guidelines scheme should be reconfigured to more accurately reflect the ways in which sentences for intellectual property crimes are imposed in practice.

II. Federal Sentencing Practice and Booker

To frame the issues that this article explores, this section provides a brief overview of federal sentencing practice and of the Booker decision.

A. Pre-Booker Sentencing Procedures and Practice

Under the Sentencing Reform Act,[9] Congress restricted district courts’ sentencing authority. The Act directed courts to consider a broad variety of purposes and factors before imposing sentences, including the sentencing guidelines and other “policy statements” promulgated by the United States Sentencing Commission.[10] Although the Sentencing Reform Act directed judges to consider a broad set of sentencing considerations, the Act did not grant judges much discretion in sentencing, as sentences were restricted to the ranges set forth in the Guidelines sentencing grids, and sentences were subject to a variety of standards of review on appeal.[11]

In particular, 18 U.S.C. § 3553(b) constrained a court’s sentencing discretion unless the court found valid reasons for departing from the Guidelines sentence.[12] Departures were authorized only when a court found “an aggravating or mitigating circumstance of a kind, or to a degree, not adequately taken into consideration by the Sentencing Commission in formulating the guidelines that should result in a sentence different from that described.”[13]

Because of these constraints, before Booker, “[a] court’s authority to depart from the applicable range [was] circumscribed.”[14] Thus, before a departure was permitted, “certain aspects of the case [had to be] unusual enough for it to fall outside the heartland of cases in the Guidelines.”[15]

B. Post-Booker Sentencing Procedures and Practice

Booker fundamentally changed the law of federal criminal sentencing and gave district courts newfound discretion over sentencing decisions.[16] In Booker, a five-Justice majority concluded that the system of mandatory Guidelines was unconstitutional because that system violated the Sixth Amendment’s requirement that “[o]ther than the fact of a prior conviction, any fact that increases the [maximum penalty to which a defendant may be subjected] must be submitted to a jury, and proved beyond a reasonable doubt.”[17]

A different five-Justice majority concluded that the proper remedy was not to eliminate the Guidelines entirely, or to eliminate any fact-finding related to sentencing, but to make the Guidelines “effectively advisory.”[18] Having eliminated those portions of the Sentencing Reform Act[19] that made the Guidelines mandatory, the Booker court determined that (1) district courts “must consult”[20] the now-advisory Guidelines and (2) appellate review of sentences for reasonableness would be made in light of the “numerous factors” set forth in 18 U.S.C. § 3553(a), including the applicable advisory guidelines range.[21]

Although Booker rendered the Guidelines advisory,[22] the Supreme Court later clarified that “[i]f the sentence is within the Guidelines range, the appellate court may, but is not required to, apply a presumption of reasonableness.”[23] Underscoring the importance of careful judicial fact-finding in a Guidelines-advisory system, the Supreme Court also observed that the greater a sentence deviates from the applicable guidelines, the greater the justification the judge must place on the record: “We find it uncontroversial that a major departure should be supported by a more significant justification than a minor one. After settling on the appropriate sentence, [the sentencing judge] must adequately explain the chosen sentence to allow for meaningful appellate review and to promote the perception of fair sentencing.”[24],[25]

Some have suggested that Booker‘s emphasis on judges providing specific explanations for their sentences renders federal sentencing more balanced, transparent, and proportional by (1) improving the balance between the application of structured sentencing rules and judicial discretion; (2) improving the balance between the impact of judicial and prosecutorial discretion at sentencing; (3) improving the opportunities for district judges to exercise reasoned sentencing judgment to tailor sentences to individual case circumstances; [and] (4) reordering sentencing outcomes (at least slightly) so that those defendants most deserving of reduced (or increased) sentences are getting the benefits (or detriments) of expanded judicial authority to sentence outside the Guidelines.[26]

III. Analysis of Sentencing Trends for Intellectual Property Crimes

A. Methodology

To identify and investigate trends specific to sentencing for intellectual property offenders, this article analyzes comprehensive, publicly available data sets from the United States Sentencing Commission covering sentences imposed from 1997 to 2011 for all crimes generally, for intellectual property crimes,[27] and for selected comparable economic crimes.[28] The economic crimes selected as comparators to intellectual property crimes[29] were (1) “Larceny, Embezzlement, and Other Forms of Theft; Offenses Involving Stolen Property; Property Damage or Destruction; Fraud and Deceit; Forgery; Offenses Involving Altered or Counterfeit Instruments Other than Counterfeit Bearer Obligations of the United States[30],” and (2) “Offenses Involving Counterfeit Bearer Obligations of the United States.”[31]

These comparator economic crimes were chosen because they, like intellectual property crimes, involve one or more elements of forgery, deceit, fraud, or counterfeiting. Forgery and counterfeiting are particularly suitable analogs to infringement of copyright or trademarks, as forgery, counterfeiting, and infringement all involve a party attempting to pass off a good or a work as having been produced by another party. Also, like intellectual property crimes, the comparator crimes do not involve an element of physical force. Although these crimes may not be precisely comparable to intellectual property crimes in all ways, they serve to illustrate the unique treatment that intellectual property offenders receive in comparison to offenders in general, and in comparison to other economic crime offenders.

B. Findings and Analysis

An analysis of sentencing trends for intellectual property crime offenders reveals several critical differences between the ways in which judges impose sentences on intellectual property offenders as compared to other offenders, including economic crime offenders.

1. Growth in Intellectual Property Offenders Sentenced

The number of defendants sentenced under an intellectual property guideline has grown 50% faster since 1997 than the number of defendants sentenced overall.[32] There are several possible explanations for this trend. First, committing an intellectual property crime, particularly copyright infringement, is not very capital-intensive, and may thus be easier to perpetrate than other crimes that require capital investment.[33] Also, unlike theft, fraud, or embezzlement, committing an intellectual property crime does not require person-to-person contact; all that is necessary to commit an intellectual property crime is to obtain a protected work or item, replicate the work or item, and then disseminate the replica. Second, as actors, both individual and corporate, find that more and more of their value is bound up in their intellectual property,[34] the owners of that intellectual property may be more keen on enforcing their rights. Whatever the cause or causes of this growth, the growth in intellectual property crimes necessitates careful review and understanding of the ways in which intellectual property offenders are punished.

2. Proportion of Non-Guidelines Sentences Imposed on Intellectual Property Offenders

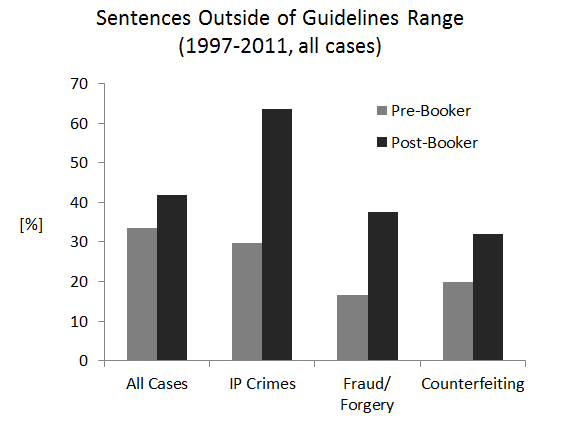

A second trend that emerges from the sentencing data is that the proportion of outside-Guidelines sentences imposed for intellectual property crimes is far greater than the proportion of outside-Guidelines sentences imposed for crimes in general and for other economic crimes. The chart below illustrates this trend:

As shown in the figure above,[35] the Booker decision brought significant changes to the way intellectual property sentences are imposed. Before Booker, intellectual property offenders received outside-Guidelines sentences only about 30% of the time, which was less frequent than the 33% average for all offenders. After Booker, however, intellectual property defendants receiving outside-Guidelines sentences increased to nearly 65%. Put another way, although nearly 65% of intellectual property offenders after Booker received below-Guidelines sentences,[36] less than 40% of all offenders and of economic crime offenders received outside-Guidelines sentences after Booker.

The fact that two out of every three intellectual property offenders receives an outside-Guidelines sentence demonstrates the disconnect between the Guidelines and the way discretionary sentences are imposed. There would not be nearly so many outside-Guidelines sentences if the Guidelines were congruent with judges’ views of intellectual property crimes. Indeed, with two out of every three intellectual property offenders receiving an outside-Guidelines sentence, it appears that departing from the Guidelines has become the rule, rather than the exception. The fact that intellectual property offenders receive an outside-Guidelines sentence so much more frequently than offenders in general or economic crime offenders suggests that judges believe that intellectual property crimes are less harmful than other types of economic crimes.

While the Supreme Court in Booker was concerned with the question of the Guidelines’ constitutionality and not with whether the Guidelines were actually reflective of what judges believe the “correct” sentence should be for an intellectual property offender, the above chart illustrates that two-thirds of the time, judges do not believe that the Guidelines sentences for intellectual property offenders are appropriate. If judges are representative of the population at large, the Supreme Court was correct from a sociological perspective to render the Guidelines advisory. Mandatory Guidelines sentences would, based on the data shown above, result in two-thirds of all intellectual property defendants receiving sentences that, at least in the view of judges, are too high.

3. Frequency of Post-Booker Deviation from Sentencing Guidelines

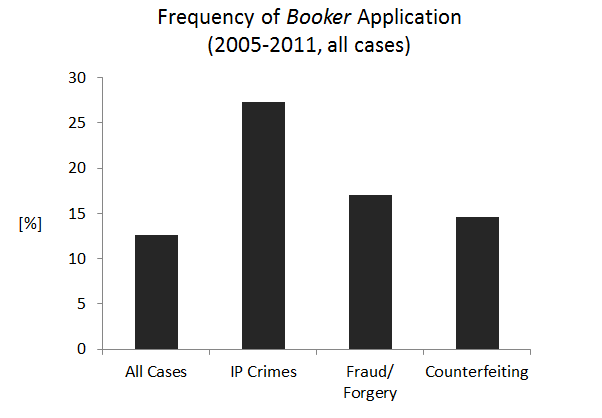

Another trend that emerges is the different frequency with which sentencing judges apply Booker to adjust sentences in intellectual property cases relative to the frequency with which judges apply Booker in other cases. The chart below illustrates this trend:

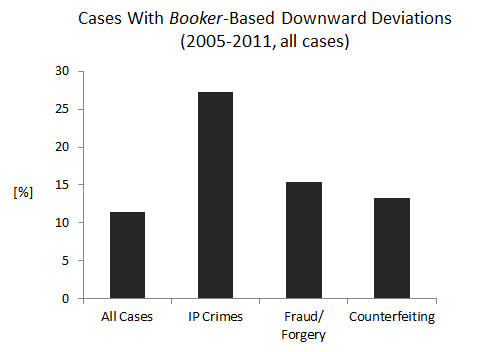

As shown in the chart above, Booker is applied in intellectual property cases about 27% of the time.[37] This figure is significantly greater than the frequency with which judges apply Booker in all criminal cases (13%), in fraud and forgery cases (17%), and in counterfeiting cases (15%). Expressed another way, judges apply Booker to adjust sentences in intellectual property cases twice as often as they apply Booker to adjust sentences in cases in general and about 60% more frequently than they apply Booker to adjust sentences in fraud and forgery cases. This too suggests that, as compared to other types of crimes, judges believe that the Guidelines sentences for intellectual property offenders are not in alignment with the severity of the offenses.

4. Proportion of Cases With Downward Deviations

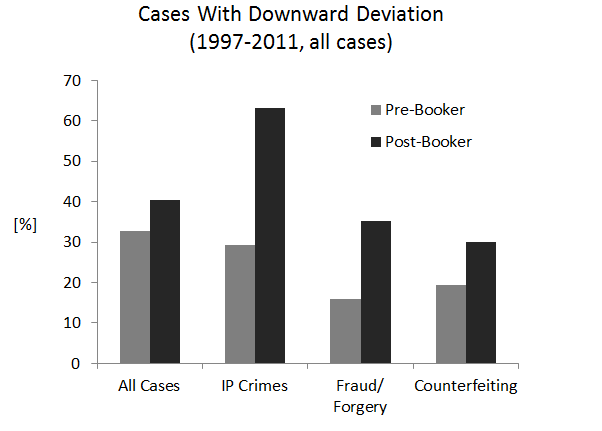

The chart below illustrates the proportion of cases from 1997 to 2011 that involved a downward deviation:[38]

As the above chart shows,[39] nearly two-thirds (i.e., well over half) of post-Booker intellectual property cases involve a downward deviation from the advisory Guidelines range.[40] This is a much larger proportion than the proportion of all cases that involve a downward deviation from the advisory Guidelines range and also much larger than the proportion of other comparable crimes cases that involve a downward deviation from the advisory Guidelines range. This trend is significant, as a sentencing regime in which two-thirds of defendants receive sentences that are below the advisory Guidelines range suggests that the judicial actors who exert influence over the sentence believe that the Guidelines-suggested sentences are unsuitable.

5. Judicial Actors Responsible for Downward Deviations

The chart above, however, presents the question of whether the increase in downward deviations after Booker is due to (1) prosecutors sponsoring more downward deviations or (2) judges initiating more downward deviations on their own. To address this question, one must compare the proportion of downward deviations due to government-sponsored deviations with the proportion of downward deviations that are based on judges exercising their post-Booker discretion.

i. Government-Sponsored Downward Deviations

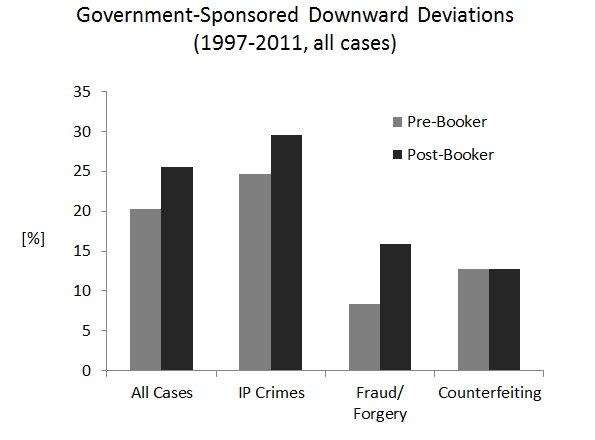

The following chart shows the proportion of cases that include a government-sponsored deviation from the advisory Guidelines sentencing range:

As shown above, the proportion of cases that included a government-sponsored downward deviation changed with the 2005 Booker decision for cases in general, for intellectual property offenders, for fraud/forgery offenders, but not for counterfeiting offenders.[41] Notably, post-Booker intellectual property offenders received government-sponsored downward deviations more frequently than did offenders in general or other economic crimes offenders.

ii. Judge-Initiated Downward Deviations

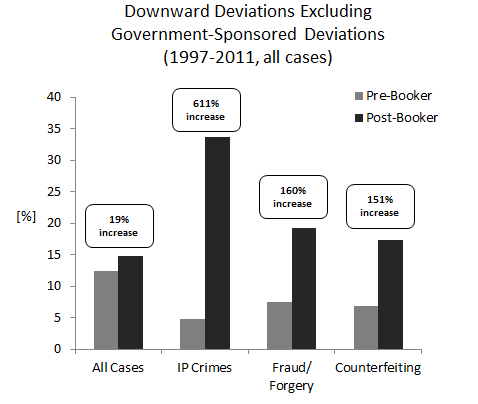

An analysis of downward deviations that were not government-sponsored, however, reveals a very different trend. The following chart illustrates the evolution of downward deviations that are not government-sponsored:

As shown above,[42] the percentage of overall cases where the judge alone granted a downward deviation shows a moderate (~19%) increase after Booker. In the case of intellectual property crimes, however, the data show that the percentage of intellectual property crimes that involved a non-government-sponsored downward deviation increased by 611% after Booker. This 611% increase is about thirty-two times the increase for cases overall and is about four times the increase in judge-initiated deviations for fraud/forgery crimes and for counterfeiting crimes. This trend suggests that once the Booker decision issued, judges had a far greater need to adjust intellectual property crime sentences than they did any other kind of sentences.

The chart above also shows that judge-initiated deviations occur after Booker about twice as frequently for intellectual property offenders than for other offenders, whereas, pre-Booker, such judge-initiated deviations occurred less frequently than for crimes in general or for other economic crimes.

Several hypotheses may explain this data. First – and most importantly for purposes of this article – one may interpret the disproportionately large increase in non-government-sponsored sentence deviations for intellectual property crimes as showing that judges, on their own post-Booker initiative, believe that the Guidelines sentences for intellectual property crimes are unsuitable and disproportionately punish intellectual property defendants relative to defendants overall and relative to defendants in other, comparable economic crime cases.[43]

Second, one may hypothesize that judges believe economic crimes are disproportionately punished relative to all cases in general, as the post-Booker data show that judges reduce sentences for economic crime offenders at a higher rate than they do for offenders overall. The fact that intellectual property crimes received the fewest judge-initiated deviations before Booker and receive the most deviations after Booker further supports the hypothesis that judges believe that Guidelines intellectual property sentences are inappropriate and that judges are willing to exercise their Booker-based discretion to address this.

6. Downward Deviations Based on Judicial Application of Booker

The following graph further supports the idea that judges believe that Guidelines for intellectual property offenders are unsuitable. This graph shows the percentage of cases in which the downward deviation was based on a judge’s application of Booker at sentencing:

As shown above,[44] judges applied Booker to effect downward sentence deviations in 27% of intellectual property cases. This rate is 138% greater than the Booker application rate for all cases, 78% greater than the Booker application rate to fraud/forgery crimes, and 105% greater than the Booker application rate to counterfeiting crimes. One may interpret this trend as further evidence that judges are significantly more inclined to modify a sentence for an intellectual property crime than for crimes in general and for other comparable economic crimes, which further supports the view the judges do not believe the Guidelines sentences for intellectual property crimes are satisfactory.

IV. Implications of Post-Booker Sentencing Trends

The foregoing data illustrate several overarching trends that apply to post-Booker sentencing in general and to post-Booker sentencing of intellectual property offenders. First, the proportion of intellectual property sentences that are outside the Guidelines-recommended range has increased significantly since Booker. Second, the proportion of intellectual property sentences that are outside the Guidelines-recommended range has increased by a far greater magnitude than the outside-Guidelines sentences for cases overall and for other economic crimes. Third, judges are far more likely to apply Booker to modify a sentence in an intellectual property case than in cases overall or in another economic crime case. These findings have several implications for the sentencing scheme and also for society’s view in general of intellectual property crimes.

A. Prospective Causes for Trends in Intellectual Property Sentences

Although the data show a number of clear trends, the causes for these trends are perhaps less clear. This may be so because a number of factors are responsible for these sentencing trends.

First, as mentioned above, intellectual property crimes may be perpetrated against corporations, as opposed to individuals. Corporations are better equipped than individuals to absorb economic harm that results from the sale or other distribution of infringing goods or works, and post-Booker sentences may have taken this into account.

The sentencing trends may also be based on the fact that copyrighted and trademarked works – which are based primarily on creativity – may be originated without significant capital investment. This may be contrasted with theft of materials synthesized by a capital-intensive production processes or with the manufacture of goods that infringe a patent that is itself the result of significant research and capital investment by the patent owner.[45]

Further, unlike the theft of tangible goods, neither copyright nor trademark infringement completely deprive the owner of the use of their right.[46] Instead, the infringement reduces the value of the right instead of depriving the owner of the ability to use their right.[47] Intellectual property crimes also involve less immediate physical risk to the victim, as fraud and counterfeit crimes may, at least part of the time, be accomplished by an offender operating from a distance without ever making any physical contact with the victim.

One might also explain the trends in intellectual property sentencing on the ground that society is becoming inured to such crimes (e.g., file sharing, knock-off goods) on account of their prevalence.[48] Some have commented that “most people” no longer consider illegal downloading from the Internet a form of theft.[49] Given that societal views of copyright infringement have evolved, the sentences that judges impose may have also evolved to mirror society’s views.

B. Implications For The Sentencing Guidelines

The above-listed trends have certain implications for the Sentencing Guidelines as they presently exist, not the least of which is that the Guidelines are not in harmony with prosecutors’ and judges’ views of the harm that intellectual property crimes cause.

First, the fact that nearly two-thirds of sentences for post-Booker intellectual property cases are below the Guidelines-recommended range suggests that prosecutors (who are responsible for government-sponsored deviations) and judges (who exercise post-Booker discretion over the imposition of sentences) believe that the Guidelines-recommended sentences for intellectual property crimes are too heavy, as both government-sponsored and judge-initiated deviations are applied to intellectual property offenders more frequently than to other offenders. This is contrary to the recent recommendations by Congress and the current administration to increase the guidelines,[50] as it appears that judicial actors believe that the penalties are too strong, not too lenient. This trend in the data is contrary to the attempts of many parties to strengthen the penalties assessed for intellectual property crimes.[51]

Second, the fact that the proportion of intellectual property cases that received judge-initiated deviations increased by 611% after Booker (as opposed to far smaller increases for crimes in general and for economic crimes specifically) suggests that judges, in particular, believe that intellectual property sentences are too stringent. If judges believed otherwise, the rate at which they downwardly adjust sentences for intellectual property crimes would not be thirty-two times greater than the rate of downward adjustments for crimes generally and would not be four times greater than the rate of downward adjustments for other economic crimes. Additionally, judge-initiated deviations occurred after Booker about twice as frequently for intellectual property offenders than for other offenders, whereas, pre-Booker, such judge-initiated deviations occurred less frequently than for crimes in general or for other economic crimes. The fact that discretion-exercising judges apply sentences to intellectual property crimes in a way that is so qualitatively different from the way they impose sentences for other crimes suggests that judges take a special view of intellectual property crimes that differs from the view taken by the United States Sentencing Commission.

The divergence of views between judges and the Sentencing Commission warrants future exploration. As discussed above, intellectual property crimes are unique – the harm to the victim is frequently inchoate and difficult to quantify,[52] and understanding judges’ and prosecutors’ views of intellectual property crimes may help the United States Sentencing Commission as that body performs its ongoing review of federal sentencing statistics.

There are several approaches to curing the disharmony between the Guidelines and the sentences that judges actually impose. First, in order to honor Congress’s intent of allowing deviations only in exceptional cases,[53] the Guideline range for intellectual property crimes should be lowered so that sentences that are presently qualified as downward deviations would be within the new, reduced advisory Guidelines range. This would result in a sentencing regime in which deviations are the exception and not the rule.[54]

Second, by creating a sentencing regime in which sentences more frequently fall into a Guidelines range, defendants and prosecutors alike can better predict the offender’s final sentence. This may have implications for defendants facing a decision to either enter a plea bargain or go to trial, as the defendant may have a better sense of his or her likely sentence following trial.

In addition, adjusting the Guidelines may better align the sentences with the attitudes of those in the judicial system that actually impose the punishments, as judges and prosecutors alike seem to agree that the guideline sentences do not align with the proper punishment. While it is of course true that judges do not set the guidelines, the United States Sentencing Commission is comprised of judges, prosecutors, and other practitioners that have carefully researched sentencing issues, and adjusting the Guidelines to conform more closely to the sentences that judges actually impose would honor the Commission’s intent to have the Guidelines serve as a guidepost for the imposition of sentences.

V. Conclusion

There is no doubt that the Booker decision effected watershed changes on federal sentencing practices. However, Booker‘s effect on the sentencing of intellectual property offenders has been even greater than its effect on cases in general and on economic crimes specifically. The fact that judges impose non-Guidelines sentences on two out of every three intellectual property offenders illustrates that the sentences prescribed by the Guidelines by and large do not align with judges’ view of intellectual property crimes. Further, the fact that judges impose non-Guidelines sentences for intellectual property crimes far more frequently than for crimes in general or for economic crimes illustrates that judges have a unique view of intellectual property crimes that differs from their views on other crimes. The data also shows that prosecutors share this special view of intellectual property crimes, as prosecutors sponsor downward deviations more frequently for intellectual property offenders than they do for offenders in general and for economic crime offenders.

Further analysis may be useful to determine the best way to assess sentences for intellectual property offenders. But until the tension between Guidelines’ recommendations and judges’ actual sentences is resolved, prosecutors and defendants alike will continue to operate in a regime where two out of every three intellectual property offenders receives a sentence that is outside the contemplation of the United States Sentencing Commission’s Guideline, thus frustrating Congress’s overarching goal of achieving predictable, uniform sentencing.[55]

[1] See Booker v. United States, 543 U.S. 220 (2005).

[2] U.S. Sentencing Guidelines Manual. An online edition of the Guidelines may be conveniently accessed at http://www.ussc.gov/Guidelines/2011_Guidelines/index.cfm (last visited May 13, 2012).

[3] See, e.g., Koon v. United States, 518 U.S. 81, 98 (1996) (observing, pre-Booker, that before departure was permitted, the case had to be “unusual enough for it to fall outside the heartland of cases in the Guidelines”).

[4] 18 U.S.C. § 3553(b).

[5] See, e.g., United States v. Gonzalez-Huerta, 402 F.3d 727, 737 (10th Cir. 2005) (en banc) (noting that Booker “drastically changed federal sentencing procedure”).

[6] Booker, 543 U.S. at 245.

[7] See, e.g., United States v. Mohamed, 459 F.3d 979, 987 (9th Cir. 2006) (post-Booker sentences reviewed only for reasonableness).

[8] Intellectual property crimes are unique for several reasons. First, infringement of an owner’s intellectual property (e.g., producing fake brand-name goods) may dilute the owner’s brand and render the owner’s brand less exclusive. Additional harm may result from intellectual property infringement if a user unknowingly buys an infringing good that does not meet the quality standard of the brand-name good, as the user may have a negative experience with the counterfeit good and elect not to purchase the brand-name good in the future. In another situation, a defendant may engage in pre-release piracy, where the defendant obtains and then disseminates (e.g., via the Internet) a pre-release copy of a movie before the movie is released in theaters. See United States v. Gonzalez, Criminal No. 03-153 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 20, 2004) (defendant convicted for posting pre-release copy of The Hulk movie on the Internet). Additional information available at: http://www.justice.gov/usao/nys/pressreleases/June03/hulkplearelease.pdf.

[9] Sentencing Reform Act of 1984, Pub. L. No. 98-473, 98 Stat. 1987 (codified as amended at 18 U.S.C. §§ 3551-3586 (1985)).

[10] 18 U.S.C. § 3553(a)(4)(A), (a)(5); see also 28 U.S.C. § 994(a)(1), (a)(2).

[11] 18 U.S.C. § 3742(e).

[12] 18 U.S.C. § 3553(b)(1), (b)(2).

[13] 18 U.S.C. § 3553(b)(1); cf. U.S. Sentencing Guidelines Manual § 1B1.1 cmt. n.1(E) (2000) (defining “departure”).

[14] United States v. Butler, 954 F.2d 114, 121 (2d Cir. 1992).

[15] United States v. Thorn, 317 F.3d 107, 125 (2d Cir. 2003) (quoting Koon v. United States, 518 U.S. 81, 98 (1996)).

[16] E.g., United States v. Gonzalez-Huerta, 403 F.3d 727, 737 (10th Cir. 2005) (en banc) (describing Booker as having “drastically changed federal sentencing procedure”).

[17] Booker v. United States, 543 U.S. 220, 231 (2005) (quoting Apprendi v. New Jersey, 530 U.S. 466, 490 (2000).

[18] Id. at 245.

[19] P.L. No. 98-473, 98 Stat. 1987.

[20] Booker, 543 U.S. at 264.

[21] Id. at 261.

[22] Id. at 245.

[23] Gall v. United States, 552 U.S. 38, 51 (2007); see also, Rita v. United States, 551 U.S. 338, 347 (2007).

[24] Gall, 552 U.S. at 50.

[25] The Booker decision and its imposition of a deferential, “reasonableness” standard of review for sentences places a premium on careful, thorough sentencing proceedings: “[a] major undercurrent of the Supreme Court’s post-Booker sentencing jurisprudence is that, in an advisory guidelines system, the defendant is entitled to an interactive sentencing in which the judge listens and explains rather than merely pronouncing a sentence from on high after having done a little Guidelines math.” United States v. Wilson, 614 F.3d 219, 227 (6th Cir. 2010) (Martin, J. concurring).

[26] Douglas A. Berman, Tweaking Booker: Advisory Guidelines In The Federal System, 43 Hous. L. Rev. 341, 352 (2006); see also James G. Carr, Some Thoughts on Sentencing Post-Booker, 17 Fed. Sentencing Rep. 295, 297 (2005) (observing that from the viewpoint of sentencing judges, “[s]ince Booker, we have balance and control. Before, we had neither.”).

[27] Federal criminal law punishes only infringements of copyright and trademark rights; infringement of patent rights is not subject to criminal penalties. For an in-depth analysis of the issues associated with imposition of criminal sanctions for patent infringement, see Irina D. Manta, The Puzzle of Criminal Sanctions for Intellectual Property Infringement, 24 Harv. J. L. & Tech. 469 (2011). Professor Manta notes that imposition of criminal sanctions for patent infringement would indicate that society prizes patent rights as much as other forms of intellectual property. Id. at 494. The clear corollary is that the lack of such sanctions implies that patent rights are not as valued by society as are other forms of intellectual property.

[28] Data is available from the data and statistics section of the United States Sentencing Commission’s website, see United States Sentencing Commission Data and Statistics, http://www.ussc.gov/Data_and_Statistics/index.cfm.

[29] U.S. Sentencing Guidelines Manual § 2B5.3 citing 17 U.S.C. §§ 506(a), 1201, 1204; 18 U.S.C. §§ 2318-2320, 2511 (setting forth sentencing guidelines for IP crimes, including criminal copyright infringement, circumvention of copyright systems, and trafficking counterfeit copyrighted goods).

[30] U.S. Sentencing Guidelines Manual § 2B1.1 citing 7 U.S.C. §§ 6, 6b, 6c, 6h, 6o, 13, 23; 15 U.S.C. §§ 50, 77e, 77q, 77x, 78j, 78ff, 80b-6, 1644, 6821; 18 U.S.C. §§ 38, 225, 285-289, 471-473, 500, 510, 553(a)(1), 641, 656, 657, 659, 662, 664, 1001-1008, 1010-1014, 1016-1022, 1025, 1026, 1028, 1029, 1030(a)(4)-(5), 1031, 1037, 1040, 1341-1344, 1348, 1350, 1361, 1363, 1369, 1702, 1703 (if vandalism or malicious mischief, including destruction of mail, is involved), 1708, 1831, 1832, 1992(a)(1), (a)(5), 2113(b), 2282A, 2282B, 2291, 2312-2317, 2332b(a)(1), 2701; 19 U.S.C. § 2401f; 29 U.S.C. § 501(c); 42 U.S.C. § 1011; 49 U.S.C. §§ 14915, 30170, 46317(a), 60123(b) (setting forth sentencing guidelines for fraud and forgery crimes).

[31] U.S. Sentencing Guidelines Manual § 2B5.1 citing 18 U.S.C. §§ 470-474A, 476, 477, 500, 501, 1003 (setting forth sentencing guidelines for counterfeit crimes involving U.S. bearer obligations).

[32] U.S. Sentencing Guidelines statistics materials 1997-2011, available at http://www.ussc.gov/Research_and_Statistics/index.cfm.

[33] See David G. Post, In Search of Jefferson’s Moose: Notes on the State of Cyberspace 202 (2009) (noting “the remarkable facility with which Internet users have been able to reproduce and redistribute information of all kinds—music, text, video, etc.—whether ostensibly protected by some nation’s copyright law or now, in quantities that truly stagger the mind“) (emphasis added).

[34] According to one study, in 1978, 80% of corporate assets were tangible assets (e.g., physical assets) and the remaining 20% were intangible assets. By 1997, these had reversed, such that 73% of corporate assets were intangible assets. Kenneth E. Krosin, Management of IP Assets, AIPLA Bull. (Am. Intell. Prop. L. Ass’n), 2000 Mid-Winter Meeting Issue, at 176.

[35] The change in the proportion of outside-Guidelines sentences before Booker and after Booker was statistically significant (p < 0.01) for all cases, for IP crimes, for fraud/forgery crimes, and for counterfeiting crimes. The difference between the proportion of outside-Guidelines sentences imposed after Booker for IP crimes and the proportion of post-Booker outside-Guidelines sentences for all crimes was statistically significant (p < 0.01). The differences between outside-Guidelines sentences imposed after Booker for IP crimes and the proportion of post-Booker outside-Guidelines sentences for fraud/forgery crimes and for counterfeit crimes were also statistically significant (p < 0.01 in both cases), further underscoring that IP crimes are treated differently after Booker than are comparable economic crimes.

[36] Less than 1% of all defendants received above-Guidelines sentences.

[37] The difference between the frequency of Booker application in IP crimes and the frequency of Booker application for all crimes, or for fraud/forgery crimes, or for counterfeit crimes, was statistically significant (p < 0.01). Interestingly, the difference between the frequency of Booker application for counterfeiting crimes and for all crimes in general was not as statistically significant (p < 0.30).

[38] This chart is similar to the previous chart illustrating the proportion of cases with outside-Guidelines sentences, as more than 99% of outside-Guidelines cases involve sentences that are below the advisory Guidelines range.

[39] The difference between the pre- and post-Booker frequency of downward deviations was statistically significant (p < 0.01) for all crimes, IP crimes, fraud/forgery crimes, and counterfeiting crimes. The difference between the frequency of post-Booker downward deviations for IP crimes as compared to the frequency of post-Booker downward deviations for all crimes, fraud/forgery crimes, and counterfeiting crimes was also statistically significant (p < 0.01).

[40] As explained above, because less than 1% of all defendants received above-Guidelines sentences, the vast majority of outside-Guidelines sentences are below the advisory Guidelines range.

[41] The difference between the pre- and post-Booker frequency of government-sponsored downward deviations was statistically significant (p < 0.01) for all crimes and for fraud/forgery crimes. The difference between the pre- and post-Booker frequency of government-sponsored downward deviations was less significant for IP crimes and was unchanged for counterfeiting crimes.

[42] The difference between the pre- and post-Booker frequency of non-government-sponsored downward deviations was statistically significant (p < 0.01) for IP crimes, fraud/forgery crimes, and counterfeiting crimes, but was not as significant (p < 0.28) for crimes overall. The difference between the frequency of post-Booker downward deviations for IP crimes as compared to the frequency of post-Booker downward deviations for all crimes, fraud/forgery crimes, and counterfeiting crimes was statistically significant (p < 0.01).

[43] One may also view the modest increase in judge-initiated deviations for cases overall as showing that, in general, judges believe that the advisory Guidelines sentences are too harsh.

[44] The difference between the frequency of Booker application to effect downward sentence deviation in IP crimes and the frequency of Booker application for all crimes, fraud/forgery crimes, or counterfeit crimes was statistically significant (p < 0.01).

[45] Aside from the costs of developing a patentable product, patent applications are far more expensive than are trademark or copyright applications. In terms of average application costs, a patent application costs about $20,000, a trademark application ranges from $500 to thousands dollars, and a copyright application costs $35. Manta, supra note 27, at 495 n.178 (2011) (citations omitted).

[46] Id. at 475. (“Indeed, because IP tends to be both intangible and non-rivalrous, its infringement causes at most a reduction in value as opposed to a genuine ‘taking’ of the good. Perhaps in the criminal context such infringement would often be more akin to other property crimes than it is to theft.”)

[47] See Dowling v. United States, 473 U.S. 207, 217 (1985) (observing that “[t]he infringer invades a statutorily defined province guaranteed to the copyright holder alone . . . he does not assume physical control over the copyright; nor does he wholly deprive its owner of its use.”); see also Stuart P. Green, Op-Ed., When Stealing Isn’t Stealing, N.Y. Times Mar. 28, 2012, at A27, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/29/opinion/theft-law-in-the-21st-century.html?pagewanted=all (“If Cyber Bob illegally downloads Digital Joe’s song from the Internet, it’s crucial to recognize that, in most cases, Joe hasn’t lost anything.”).

[48] See Manta, supra note 27, at 517 (observing that (1) “given the widespread culture of file-sharing,” copyright law may be perceived as “criminalizing ‘everybody'” and (2) that the public “does not accept” the claim that the “downloading of copyright works . . . is morally wrong and deserving of criminal sanction”); Post, supra note 33 (noting the “remarkable facility with which Internet users have been able to reproduce and redistribute information of all kinds – music, text, video, etc. – whether ostensibly protected by some nation’s copyright law or now, in quantities that truly stagger the mind.”) (emphasis added).

[50] Stop Online Piracy Act, H.R. 3261, 112th Cong. § 204; Administration’s White Paper on Intellectual Property Enforcement Legislative Recommendations 1-8 (March 2011), available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ip_white_paper.pdf.

[51] Brian P. Heneghan, The NET Act, Fair Use, and Willfulness – Is Congress Making a Scarecrow of the Law?, 1 J. High Tech. L. 27, 44 (2002) (“The Software Publishers Association even urged Judge Conaboy of the U.S. Sentencing Commission to adopt an emergency amendment to the sentencing guidelines to allow for the earliest possible implementation of the NET Act.”); Konrad Gatien, Internet Killed the Video Star: How In-House Internet Distribution of Home Video Will Affect Profit Participants, 13 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L. J. 909, 956 (2003) (“[to] combat international video piracy, the MPAA has set up an extra-judicial worldwide Internet enforcement group[.] This group consults with a former U.S. Department of Justice attorney who is well-versed in computer crime, and lobbies the U.S. trade representative to help “make sure trading nations are doing their part tracking down and prosecuting pirates”).

[52] See Green, supra note 47 (“If Cyber Bob illegally downloads Digital Joe’s song from the Internet, it’s crucial to recognize that, in most cases, Joe hasn’t lost anything”).

[53] E.g., United States v. Leon, 341 F.3d 928, 931 (9th Cir. 2003) (applying non-deferential, de novo standard of review to sentence that departed from Guidelines range); see also Prosecutorial Remedies and Other Tools to end the Exploitation of Children Today Act of 2003 (“PROTECT Act”), Pub. L. No. 108-21, 117 Stat. 650, 670 (2003) (changing standard of review for decisions to depart from the Guidelines to de novo).

[54] As described above, two out of every three IP offenders receive a sentence that is below the suggested Guidelines range.

[55] U.S. Sentencing Guidelines Manual, ch. 1, pt. A, introductory cmt. (2000).