Social media may prove to be a new tool in United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) searches. In its privacy policy, Meta purports to only comply with government requests for user information when those requests are “consistent with applicable law” and the company’s own policies. Among these is Meta’s Data Policy, which includes its Corporate Human Rights Policy, that “strive[s] to offer specific measures to protect the safety and well-being of human rights defenders as a user group.” Yet, a recent crop of challenges to ICE subpoenas for user information calls into question how faithfully Meta lives up to these commitments.

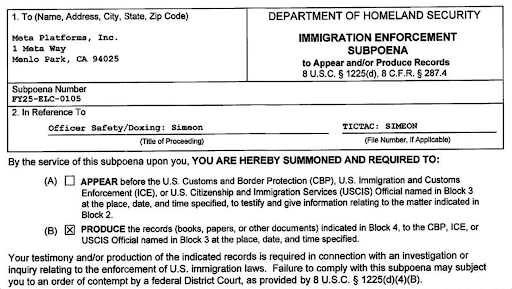

In September, the developer behind StopICE.net, a nationwide mobile alert system that tracks and reports ICE raids, received an email from Meta’s Law Enforcement Response Team three days after sharing a video on its Instagram account. The video identified a Border Patrol agent involved in multiple immigration raids in Los Angeles. Meta’s email informed the developer that a law enforcement agency sought information about their account and that the user had ten days to file a motion to challenge the request. If no motion was filed, Meta would fulfill the request. When pressed for more information, Meta sent a redacted copy of the subpoena. It revealed that the request was made by an agency within the Department of Homeland Security pursuant to 8 U.S.C. § 1225(d), a provision granting immigration officers authority to demand documents “relating to the privilege of any person to enter, reenter, reside in, or pass through the United States” or “concerning any matter which is material and relevant to the enforcement of” U.S. immigration law.

Civil rights advocates argue that this application of § 1225(d) is improper because the subpoena states the request is part of a “criminal investigation” about “officer safety” rather than a civil inquiry having to do with immigration enforcement. Not only is this use of the statute legally tenuous, but it also threatens the First Amendment rights of a group that may qualify as a human rights defender.

Crucially, § 1225(d) subpoenas are non-self-executing, meaning that they are not automatically enforceable. Thus, Meta was under no obligation to respond to the legally dubious request. The company’s willingness to do so, despite the lack of legal consequences for ignoring the request, raises serious questions about whether the company is indeed, as it claims, individually examining requests, ensuring requests’ compliance with applicable law, and taking steps to protect the safety and well-being of human rights defenders as a user group.

Users may be able to halt online platforms’ compliance with an improper government request by filing a motion to challenge it, but only if they receive timely notice of the request. This system places a heavy burden on users. Some may miss the short notice window to file a challenge, while others may lack the resources to pursue legal action. Moreover, it is impossible for users to verify whether companies like Meta are actually providing notice in all cases. How can users trust Meta to resist overbroad gag orders, or not yield to unenforceable gag orders, like those ICE may attach to their requests pursuant § 1225(d)?

Unfortunately, there are no surefire legal guardrails to prevent online platforms from abusing their discretion and misrepresenting how they handle law enforcement requests for user data. The Federal Trade Commission has broad authority to reign in deceptive business practices. For example, under the previous Trump administration, FTC Chairman Joseph Simons imposed a $5 billion fine on Meta (then Facebook Inc.) for violating a 2011 consent order that barred the company from making misrepresentations about the privacy or security of users’ personal information. Yet, because the FTC retains discretion over when and how it wields its powers and because FTC consent orders cannot be privately enforced, accountability remains inconsistent.

Legal advocates seeking to discourage online platform’s compliance with improper requests might draw upon lessons learned in recent state lawsuits against Meta and other social media companies. Those cases allege misrepresentation regarding the various platforms’ addictive design and safety hazards. Given Meta’s explicit statements in its privacy policy about how it handles law enforcement requests, similar civil proceedings against the company for misrepresentation could be brought. However, this too is an uncertain path. Threshold elements and interpretations of misrepresentation claims vary widely by jurisdiction, and the few claims that have survived motions to dismiss are still awaiting adjudication.

Another possible route is state legislation. State lawmakers could require online platforms to clearly articulate their procedures for answering law enforcement requests and give their attorneys general the power to audit these companies’ compliance with their policies. Both California and New York passed similar laws in relation to social media companies’ terms of service and content moderation policies. However, courts may push back against compelling companies to disclose these kinds of policies and procedures. Arguing that content moderation policies cannot be considered commercial speech and therefore cannot be compelled under the First Amendment, X successfully blocked part of the California bill mandating that the platform submit a semi-annual report to California’s AG detailing definitions of content categories, content moderation practices, and information on content flagged. X filed a similar lawsuit this past summer to challenge New York’s version of the law.

While these platforms’ privacy policies appear to misrepresent their actual procedures regarding law enforcement requests, their existence provides some hope for accountability. Whether that accountability will materialize, however, remains doubtful. For now, the legal infrastructure for remedying these online platforms facilitation of arbitrary and improper ICE surveillance – contrary to their own stated policies – is decidedly weak.