Jessica Silbey* & Samantha Zyontz**

Download a PDF version of this article here.

In the internet age, the copyright de minimis defense has increased in relevance as copyright lawsuits (and IP generally) are more mainstream and infringement liability more widespread. This Article is the first empirical analysis of copyright de minimis defense cases, collecting and analyzing all such decisions since the mid-19th century. It traces the doctrine’s development over the past century and its evolution in the digital era, when copying has become even more ubiquitous but its triviality remains widely disputed. The Article’s aim is not only to map the de minimis defense to learn more about it doctrinally—asking when is copying “too little” and how is that evaluated—but also asks the deeper, unresolved question about the harm copyright law aims to prevent and the benefits towards which it aims. In doing so, it proposes new rules for the de minimis defense designed to revive its appropriate function and filter out unmeritorious and inefficient copyright cases.

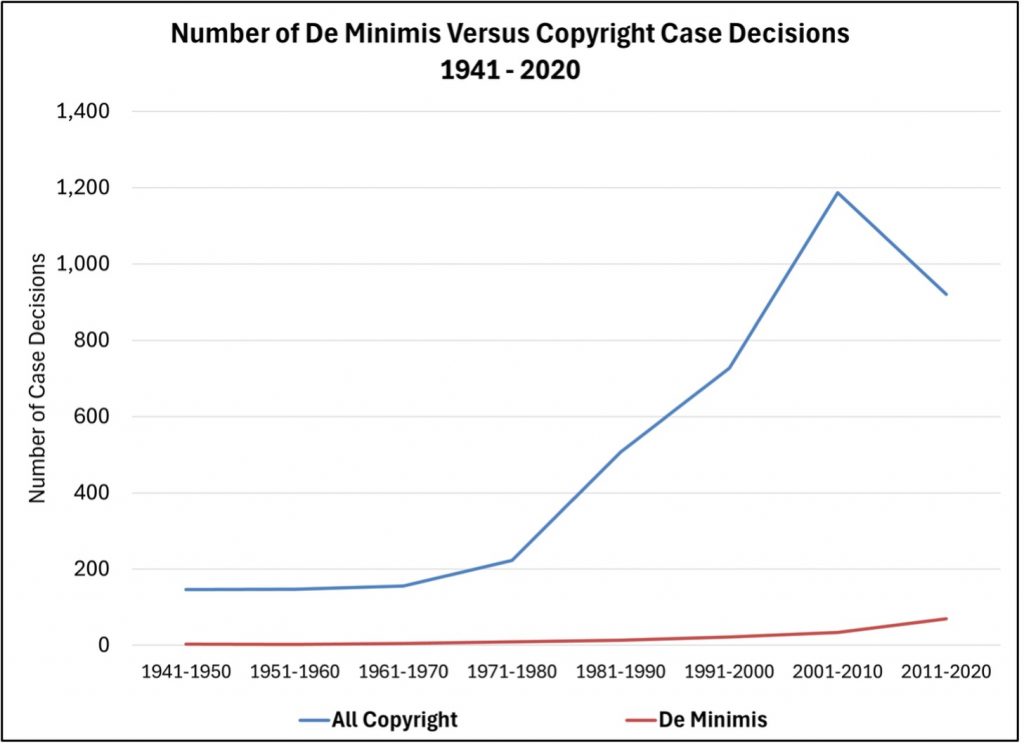

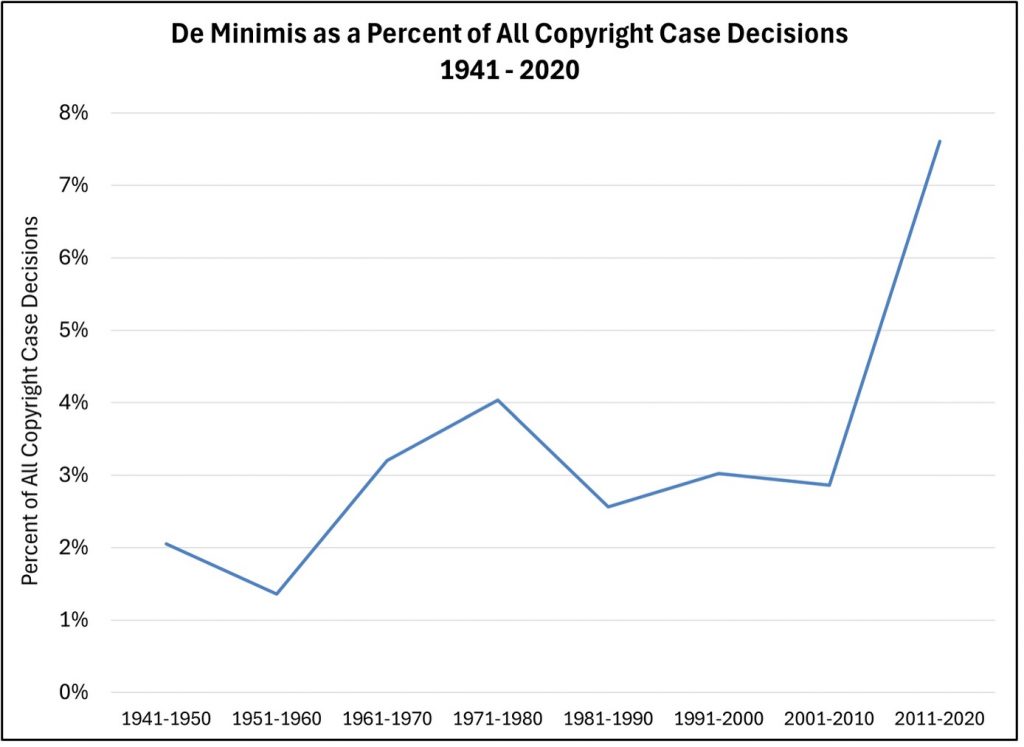

The Article begins with the hypothesis that, in the digital era, the copyright de minimis defense should be more relevant and more successful: as much as there is more copying on the internet, most of it is trivial. The data shows the first to be true (rise in relevance) but not necessarily the second (litigation success rates). Indeed, invocation of the de minimis defense has grown, but not its success in litigation, suggesting judicial skepticism toward the idea of trivial copying. That skepticism bodes poorly for the information age in which copying small bits of expression (or whole works momentarily) is essential for communication. The Article’s deep dive into the de minimis defense further explains how its evolution affects other aspects of copyright law, opening opportunities and exposing pitfalls in the context of strategic litigation. In the end, freedom of expression and the progress of science are at stake, and revitalization of the de minimis doctrine is a key to preserving these fundamental tenets of U.S. copyright law.

Introduction

De minimis non curat lex. The law does not concern itself with trifles.1It is a centuries’ old legal defense across many areas of law and essential to efficient dispute resolution.2 Despite its ubiquity and importance, little scholarship or theoretical analysis exists elucidating the nature of a “trifle” or the circumstances when the rule is best applied in specific legal fields.3 The challenge of studying the de minimis doctrine may arise because of the nature of the defense: in the face of an insubstantial injury, courts dismiss claims with little analysis or reasoning.4 What is there to learn from these terse decisions except that judges appear to know a trifle when they see one?5

In the age of artificial intelligence scooping up massive amounts of information, the meme-ification of digital communication on social media, and the ubiquity of copy/paste technology embedded in all of our electronic devices, the de minimis doctrine is (or should be) having a heyday, especially for copyright law. What counts as “too little” or “insignificant” copying to stall a frivolous lawsuit? The answer may be dramatically different from what counted as insignificant over a century ago when the de minimis doctrine entered copyright law. The de minimis doctrine is the difference between a lawsuit quickly dismissed (or never instigated) and one that costs millions of dollars to litigate. The line should be clearer, but it’s not. This Article investigates the changes in that line over a century, grounding the doctrine to its ancient roots in the common law.

De minimis injuries range from quantitatively small harms to those that are qualitatively insignificant.6 Intriguingly, some kinds of cases appear to be less susceptible to a de minimis defense, such as those concerning trespass and real property, and fiduciary law.7 Other kinds of claims, such as defamation and nuisance, more frequently elicit a de minimis defense.8 What makes one type of complaint de minimis and another worthy of adjudication within a specific field of law?

Within copyright law, plaintiffs launch time-consuming and costly legal claims presumably because they believe their copyright injuries deserve redress.9 And yet the de minimis defense succeeds because a court determines the injury is not cognizable. Frustrated copyright plaintiffs are told that despite defendant’s technical legal violations—an unauthorized copy was made—the court “does not concern itself with trifles.”10 At the heart of many cases resolved on de minimis grounds is a fundamental disagreement about the seriousness of the plaintiff’s harm and the importance of judicial efficiency to justice writ large.

When a court balances the call to adjudicate a cognizable copyright injury with preserving necessary judicial resources, the question presented is the nature and extent of the copying, not whether copying has occurred. Copying is not infringement. It’s the nature of the copying that matters.11 The copyright de minimis analysis thus becomes a question of the kind of harm copyright law aims to prevent, because copying per se is not unlawful.12 This is a harder question than might appear.13 In copyright law, what matters is the use to which the copying is put, not the fact of copying.14 A study of de minimis copyright may thus be helpful to clarify the nature and scope of cognizable copyright harms, which have been enduring and evolving questions in the field.15

The copyright de minimis doctrine has a long history that has shapeshifted over time.16 In the internet age, the copyright de minimis defense has increased in relevance as copyright lawsuits (and IP generally) are more mainstream and infringement liability more widespread.17 The digital age has made the copyright de minimis defense more relevant than ever. As artificial intelligence trained on copyrighted works has begun to dominate all areas of technology and society, whether those AI systems are making de minimis copies or causing substantial copyright harms is a question that could make or break the technology.18 In everyday life, we copy whole photographs and articles to send to friends and colleagues via email, text, and social media as essential forms of communication and discussion. When engaging in research, making our own art, and writing about the world around us, we inevitably copy bits of other copyrighted work; sometimes we copy the whole work and put it to productive and non-harmful uses. All these ubiquitous and quotidian activities implicate the copyright de minimis defense. This Article examines the patterns in assertions and analyses of the copyright de minimis defense over the past century and specifically in our digital era when copying is omnipresent but its triviality widely disputed. The Article’s aim is three-fold: (1) to map the de minimis defense as a way to learn more about it doctrinally—when is copying too much?; (2) to clarify the standard for the de minimis defense to better achieve its goal of judicial economy; and in doing so (3) to address the deeper questions about the harm copyright law aims to prevent in order to facilitate (and not chill) more communication and authorship in the digital age.19

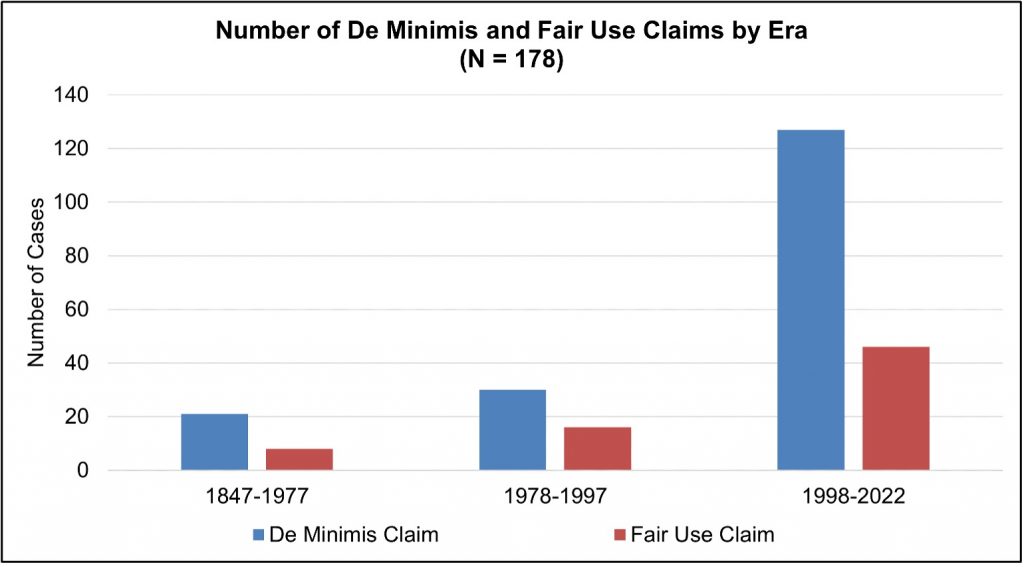

This is the first empirical study of copyright lawsuits in which courts engage in some analysis of the de minimis defense.20 The study begins with the hypothesis that in the digital era the copyright de minimis defense should be more relevant and more successful because, as much as there is more copying on the internet, most of it is trivial.21 The data shows the first to be true (more relevant) but not the second (litigation success rate). There is indeed a rise in the use of the de minimis defense in litigation, but not of its success in court.22 Under what circumstances does the defense succeed? This Article answers this question within the range of contexts reflected in the diversity of cases.

In doing so, related copyright doctrines also come under scrutiny, such as: the “substantial similarity test” for reproduction infringement; the fair use defense, which unlike the de minimis defense, arises after a finding of infringement; and the anti-aesthetic discrimination principle, which counsels courts to avoid aesthetic judgment when evaluating copyright infringement claims.23 Each of these copyright rules relate to the evolution of the de minimis doctrine in some way. And, thus, mapping the de minimis doctrine over the past century adds to our understanding of these core and more common copyright doctrines.

As copyright adapts to technology that enables promiscuous copying and prolific collage, the vitality of the de minimis defense needs closer inspection. Doing so reveals opportunities to clarify the de minimis doctrine for future application, reestablishing its independence from infringement and fair use analyses and making de minimis a more useful defense. Because copying per se is not necessarily copyright infringement, there must be some copying less than “substantial” that is beyond copyright law’s reach. As this Article demonstrates, courts have long been engaging in some form of quantitative or qualitative analysis of copying when applying the de minimis defense. Analyzing the features and trends of those assessments may help preserve the tort-like nature of copyright, whereby threshold liability does not depend on proving the act occurred (copying) but instead on balancing harms from copying with benefits of dissemination and use.24 Doing so also sharpens our focus on other critical aspects of copyright law, such as a bloated substantial similarity test or a stingy fair use analysis, which may both be causing trouble for copyright’s constitutional prerogative of promoting the progress of science.25

There are only four scholarly analyses of the copyright de minimis doctrine, but none are empirical.26 A few court cases from the past two decades discuss the copyright de minimis defense in detail and have become doctrinal benchmarks for its initial assessment.27 The facts of those cases range widely, from a fleeting glimpse of a whole copyrighted pictorial work in the background of a film to the use of a musical fragment from one musical work in another.28 But whether they reflect long-standing past practice or a change is unclear without the bigger picture. This Article will for the first time combine doctrinal, historical, and empirical perspectives on the copyright de minimis defense to put these more recent cases in perspective.

In the end, the Article concludes with a prescriptive proposal for the application of the de minimis defense that tracks the dominant trends in the cases and conforms with the doctrine’s 19th century origins. The de minimis defense should be green-lighted at the motion to dismiss stage when copying is quantitatively or qualitatively insignificant as compared to the benefits normally derived from the exploitation of the copyrighted work. As described more fully in the Article, with some outlier exceptions, this is how the de minimis defense has been applied, but not always at the motion to dismiss stage and too often (most recently) with additional and unnecessary complexity. This Article cuts through the complexity, resets the de minimis defense for effective use by courts and litigants, and leaves the thornier questions of copyright infringement and fair use defenses for more involved copyright disputes.

The Article proceeds as follows. Part I discusses the early history of the de minimis doctrine and its 19th century origins in equity, situating its essential role outside the statutory framework to maximize judicial resources and shortcut wasteful lawsuits. Part II puts this history in context of three eras of de minimis cases, “the Early Era,” the “Transition Era,” and the “Contemporary Era.” It explains the various characteristics of the cases from each of these eras and describes several exemplary cases to illuminate each time period. In doing so it highlights patterns that eventually resolve into a de minimis defense that is clearer and more efficacious. Part III describes the de minimis data set as a whole, the method for collecting and analyzing the cases, and notable trends among the three eras, further explaining the patterns in Part II. The analysis in Part III specifically connects the themes of the “Eras Tour” in Part II with a quantitative analysis of the data, including focus on the characteristics of the cases.29 Surprising features of more recent de minimis cases emerge from this analysis, some are detrimental to judicial efficiency and others support it. Detrimental features include a wider variety of de minimis standards that complicate the terrain. Also, some standards improperly confound de minimis with substantial similarity, thwarting early dismissal and rendering the defense ineffective. Beneficial features include reviving the “technical use” standard for the de minimis defense (a non-actionable copying of a whole work), which is a historical anchor of the defense. Another beneficial trend is courts’ frequent countenance of defendant’s copying whole pictorial works in the internet age when images are more essential than ever to communication.

Part IV combines these trends and their features to propose a clarified de minimis standard to strengthen the efficacy of the defense. It explains that the narrowing and complicating of the de minimis defense is a recent trend only in the “contemporary era,” when copying has become ubiquitous and harm from de minimis copying is debatable. But laudable patterns preserving the historic defense are worth highlighting and strengthening for a revamped and clarified standard to serve judicial economy. The de facto narrowing of the de minimis defense through more complicated standards and broader liability for even insignificant copying needs to stop. Instead, a standard available on motion to dismiss, either sua sponte or by defendant’s motion, would combine quantitatively small amounts of copying with whole copies that are qualitatively insignificant as within the scope of the de minimis defense. This embraces and facilitates the digital era’s new modes of communication that rely on whole visual works such as photographs, images, and graphic art (think emojis, memes, and background visuals) which are and should continue to elude copyright liability when used referentially, informationally, in transitory or minimized fashion, or are otherwise substantively insignificant to the Defendant’s work. This comports with copyright policy and, we argue, can be solidified with modest practical changes that are anchored in the already established doctrinal framework for the defense. Doing so will revitalize the de minimis copyright defense for the digital age so that it assures judicial efficiency and aligns with purposes of copyright in the 21st century.

In a case decided in the first year of the 21st century, the copyright de minimis defense did not prevail but the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit nonetheless explained its importance.

The de minimis doctrine is rarely discussed in copyright opinions because suits are rarely brought over trivial instances of copying. Nonetheless, it is an important aspect of the law of copyright. Trivial copying is a significant part of modern life. Most honest citizens in the modern world frequently engage, without hesitation, in trivial copying that, but for the de minimis doctrine, would technically constitute a violation of law. We do not hesitate to make a photocopy of a letter from a friend to show to another friend, or of a favorite cartoon to post on the refrigerator….Waiters at a restaurant sing “Happy Birthday” at a patron’s table. When we do such things, it is not that we are breaking the law but unlikely to be sued given the high cost of litigation. Because of the de minimis doctrine, in trivial instances of copying, we are in fact not breaking the law. If a copyright owner were to sue the makers of trivial copies, judgment would be for the defendants. The case would be dismissed because trivial copying is not an infringement.30

This Article explores three eras of de minimis cases in light of the above statement of doctrine. It improves our understanding of copyright’s de minimis defense, which enhances judicial efficiency by cabining actionable claims to non-trivial copyright infractions. The Article thereby elucidates the contemporary harm copyright law aims to prevent and the benefits that non-actionable copying promotes. Doing so advantageously adjusts copyright’s contours for its optimal application in the digital age.

I. Historical Origins

Webb v. Powers (1847) may be the earliest incarnation of the de minimis doctrine in U.S. copyright law.31 It is the oldest case we identified that expressly uses the term “de minimis” in a context separate from fair use. Although fair use arose several years earlier in 1841, and was present in fair abridgement cases even earlier, Webb marks a distinct development.32 Notably, both Folsom v. Marsh, which is credited with creating the modern fair use doctrine,33 and Webb v. Powers, the first U.S. copyright case we identified as relying on the de minimis defense, were decided by the same court in the same decade.

Webb quotes Folsom only once, yet the court’s analysis proceeds like a modified fair use analysis, focusing exclusively on the quantity and significance of the material copied.34 From this decision, we see the origins of the copyright de minimis doctrine as an independent defense to infringement. At this early stage, the de minimis inquiry centered on at the “nature and value of the parts copied” and whether they are “so few and unimportant in number and value compared to the whole work.”35 That formulation remained the central inquiry well into the late twentieth century.36

In Webb, publisher of the book Flora’s Interpreter alleged that the defendant’s The Flower Vase infringed his copyright. Both books were botanical references containing categorizations and descriptions of flowers. The plaintiff alleged, in particular, that the defendant copied 20 of 148 definitions, about 156 words in total, from Flora’s Interpreter.37 The defendant admitted she relied on and “meant to use the plaintiff’s book.”38 The court nonetheless found no infringement, in part because the defendant’s book was “suited for a different class of readers.”39 The court further explained that plaintiff’s own work clearly derived from other botany books, and many of the flowers “could not be described in any other way, if described naturally and truly.”40 Beyond what may be considered imperceptible market harm and copying of uncopyrightable subject matter, the court confirmed that defendant did copy some “small part of the novelty in the arrangement” and “though small in value, such an imitation or appropriation… may be actionable…and the subject of an injunction, perhaps if easily separated from the rest of the book.”41 The court nonetheless determined that no separation was possible (on account that the copying of original material was based on organizational features), and that not only was the Master correct to refuse an injunction, but no damages would issue either.

[T]he part of the arrangement claimed to be original by the plaintiffs…was hardly sufficient to justify an injunction. A novelty in arrangement, especially so trifling as this, without any new material connected with it, seemed…to be of questionable sufficiency to be protected by a copyright. The Master seemed to be of the same opinion, on the grounds of `de minimis non curat lex.’ ~ldots~It would generally be equitable and just to let the party, under such circumstances, seek redress for it by damages in a suit at law. It is not a suitable case for the exercise of a peremptory injunction, which is chiefly to aid legal rights, and in cases of copyrights runs against specific parts copied. It is usually done to work substantial justice between the parties, rather than destroy the whole book of the defendants for the small infringement in the arrangement, if otherwise it was novel, and unexceptionable, and useful to the community. This conclusion renders it unnecessary to decide on the point how far the conduct of the plaintiffs…should bar this application, though redress might perhaps be still had at law.42

In this passage, we see combined four related observations: (1) minimal copyrightable subject matter, (2) no substitutional market harm, (3) quantitatively small and qualitatively insignificant amounts of copying, and (4) the problem of enjoining the distribution of a whole work based on “unexceptional” and “useful” similarities. The decision refers throughout (and cites in full) to the Master’s report, the crucial part of which says “whether I regard quantity or value, I am compelled to conclude that the part of the materials copied by the defendants, is too insignificant in character for the law to notice. I therefore find that there is in no respect an infringement, by the defendants, of the copyright of the plaintiffs.”43 It is a rich case to inaugurate the de minimis defense in copyright, tied as it is to the many other reasons a copyright infringement claim could fail. Notably, it lacks an analysis of substantial similarity because, of course, the plaintiff’s and defendant’s books did not resemble each other at all. The case concerned copying only very small parts, not a whole work, and thus it challenged existing conceptions of how copyright law protects authors.

Note how in Webb, the court accepts the Master’s determination in large part because injunctive relief was sought to bar the publication and distribution of Defendant’s book for the cause of reproducing only 156 words. The court also accepts that there might have been an action in law for nominal damages – which means there is perhaps a technical violation of copyright – but that the infringement was “too insignificant in character for the law to notice.”44 Legal damages were not usually available in a court of equity, and the case was dismissed. That the court seemed limited by the injunctive remedy, which was the means of copyright enforcement at the time, reinforces the conclusion that defendant committed no cognizable copyright harm.45 Scant remedies at law – nominal monetary damages – may still have been feasible in this case “only to the extent or value of the encroachment”46 by the defendant although both the Master and the court seemed doubtful given the very small amount of copying.

In the 1840s and earlier, copyright largely extended only to books as published; abridging or quoting from books was not infringement.47 Webb v. Powers is therefore an odd infringement case, except that it comes on the heels of Folsom v. Marsh, in which Justice Story held that an abridgement was an infringement.48 That case concerned defendant’s 866 page abridgment, which copied 353 pages from a 6,763 page biography of George Washington.49 L. Ray Patterson writes convincingly that the legacy of Folsom v. Marsh is to expand copyright’s monopoly by redefining infringement to include some abridgments, despite the court admitting that “a fair and bona fide abridgment of an original work is not a piracy of the copyright of the author.”50

In Folsom, Justice Story explained that defendant’s use is not “fair” because “so much is taken, that the value of the original is sensibly diminished, or the labors of the original author are substantially to an injurious extent appropriated by another.”51 Justice Story’s explanation is based on “a theory of unjust enrichment”52 and focuses on quantity taken and market harm, but is further qualified by other considerations, such as “the nature and objects of the selections made, the quantity and value of the materials used, and the degree in which the use may prejudice the sale, or diminish the profits, or supersede the objects, of the original work.”53 Justice Story explains that “none are entitled to save themselves trouble and expense, by availing themselves, for their own profit, of another man’s works, still entitled to the protection of copyright.”54 The Supreme Court would eventually overrule this latter statement about “sweat of the brow,” but not until 1991 and after a century of disputes about whether in the absence of originality the author’s labor alone justifies copyright protection.55 In the meantime, the de minimis doctrine and copyright fair use take root only six years apart as two related but distinct considerations in an equitable assessment of infringement defenses.

Six years later, Webb did not engage in a fair use analysis presumably because 156 words were just too few for a market substitutional effect. The 1831 Copyright Act gave the copyright holder “the sole right and liberty of printing, reprinting, and vending” the copyrighted work.56 There was no statutory basis for a finding of infringement “that includes the copying of a portion (even a small portion) of a copyrighted work either in form or substance.”57 But since Folsom opened the door to infringement determinations based on the quantity and quality of the copied material “and the degree in which the use may…supersede the objects[] of the original work,”58 courts could now consider harm to plaintiffs from partial copying as weighed against the benefits of such minimal copying to readers and other writers.

Webb was not about piracy; it was a case about whether copying helpful material from one book to include in another without laboring to produce those portions oneself is the kind of copying copyright law should care about. Webb adapted Folsom v. Marsh for those situations in which no copies were made, but some small amount of copying occurred. When the court in Webb decided the case as a matter of equity in defendant’s favor, it correctly dismissed the case, characterizing it about “trifles with which the law should not concern itself.”59 Webb sprouted a new copyright doctrine from Folsom‘s fair use language and held that some small amount of copying was “hardly sufficient to justify an injunction” and was defensible not because it was a fair use but because it was trivial and too “insignificant in character for the law to notice.”60 Webb v. Powers is cited well into the mid-20th century for this holding that defendant’s copying of 156 words from Plaintiff’s botany textbook was an “insubstantial invasion” of Plaintiff’s copyright for the court to take notice.61

The de minimis defense originates with the Court of Chancery as a “maxim of equity” and thus was correctly applied in Webb.62 With roots centuries old, the function of general common law doctrine is “to place outside the scope of legal relief the sorts of intangible injuries, normally small and invariably difficult to measure, that must be accepted as the price of living in society.”63 As Minnesota’s highest court explained in 1908, the maxim addresses “mere trifles and technicalities” that “must yield to practical common sense and substantial justice.”64 Over centuries, the de minimis doctrine was applied across many legal areas in which it declared diverse notions of “value” trivial (including “absolute values and relative values, monetary values and human values, public values and private values”).65 Beginning with Webb v. Powers, copyright law was part of this history.

Between 1847 and 1909 (the enactment date of a new Copyright Act, which introduced statutory damages66), there is one reported case that arguably considers the de minimis defense to defeat an infringement claim.67 The one exception is List Publishing Co. v. Keller (1887). It concerns rival “social” directories, and the court determined that defendant infringed plaintiff’s directory based on the copying of 39 fake entries.68 Its statement that “the compiler of a general directory is not at liberty to copy any part, however small, of a previous directory, to save himself the trouble of collecting the materials from original sources,” expresses the contestable notion that there is no such thing as de minimis copying.69 It also paraphrases the “sweat of the brow” doctrine from Folsom quoted above, which the Supreme Court eventually overruled.70 List Publishing is plausibly about how much copying is too much (just 39 fake entries) but also about how to prove unauthorized copying of a factual work (by seeding fake entries into a factual database). List Publishing is cited in only two mid-century cases discussing the de minimis defense.71 And its statement that a subsequent author cannot save themselves time by copying from another is no longer good law.72

These are the early origins of copyright’s de minimis defense. The nineteenth century de minimis doctrine evaluated the nature and value of the parts copied compared to the whole work in the context of copyright law’s goals: promoting the progress of science through incentivizing the production of authored works by preventing market substitution.73 From here, the de minimis defense blossomed into an independent defense for most of the twentieth century.74 More recently, however, and since the beginning of the twenty-first century, our data shows that the significance of the de minimis defense has been dwarfed by fair use and the de minimis analysis partially colonized by the substantial similarity test.75 To be sure, the de minimis defense began as an element of fair use, sharing with it the effect of exempting from infringement copying that was not a market substitute.76 But fair use today does not only concern works that merely contain small parts of another copyrighted work. It covers much more, as the statutory preamble explains.77 The de minimis defense became useful and relevant, as Webb v. Powers demonstrates, in its distinction from fair use and misappropriation (one standard for which became “substantial similarity”).78 Yet, as both fair use and misappropriation standards evolve to become more complex and fact-driven, so does the de minimis defense when it was supposed to be a quick end to a frivolous lawsuit. We track that evolution below.

II. The Eras Tour (With Apologies to Taylor Swift)

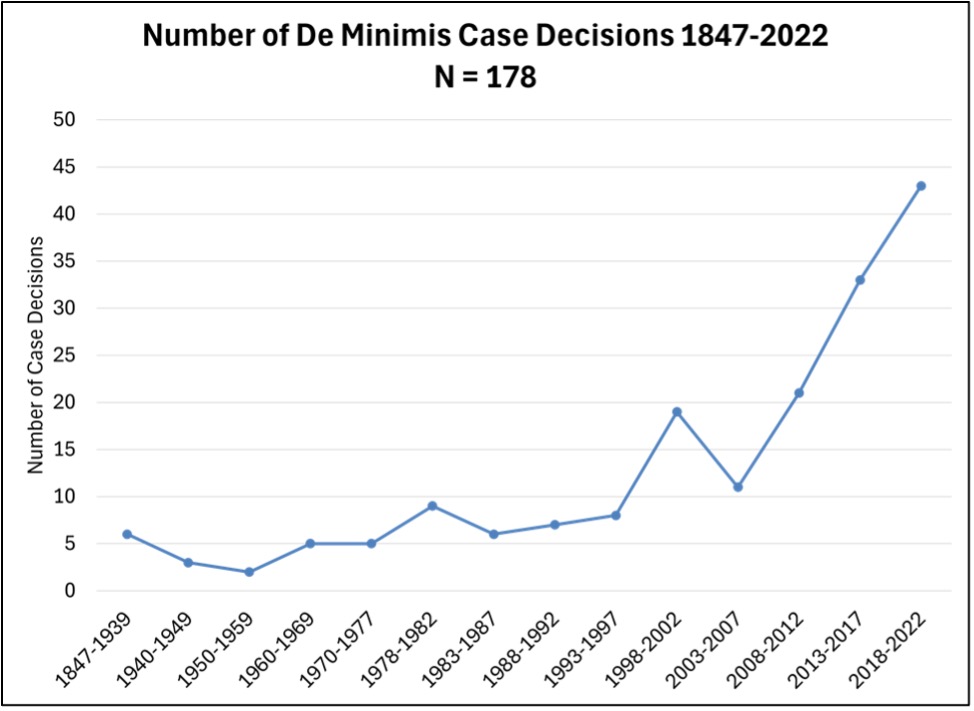

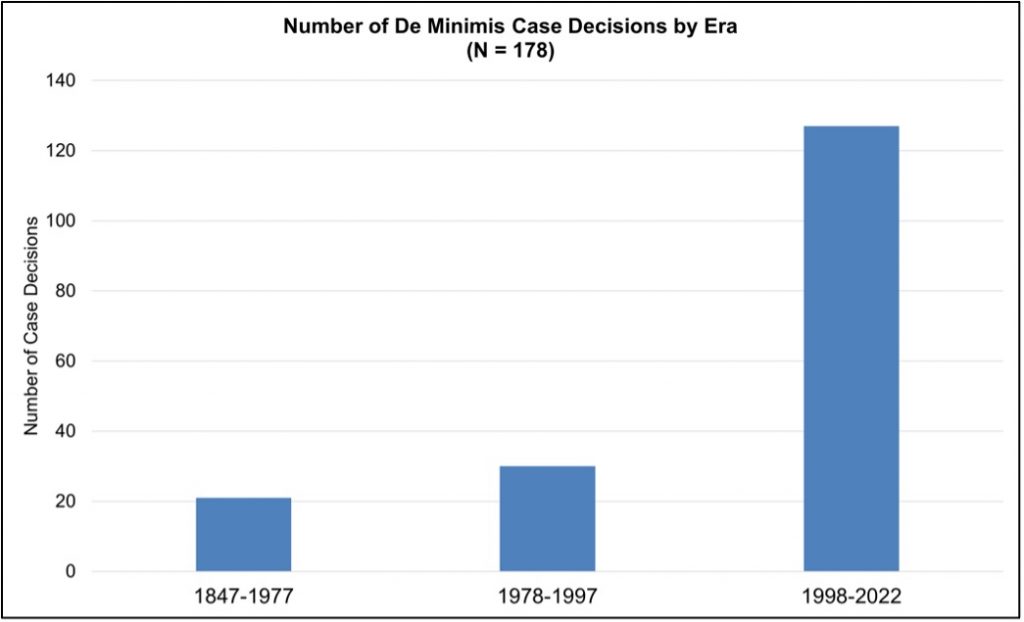

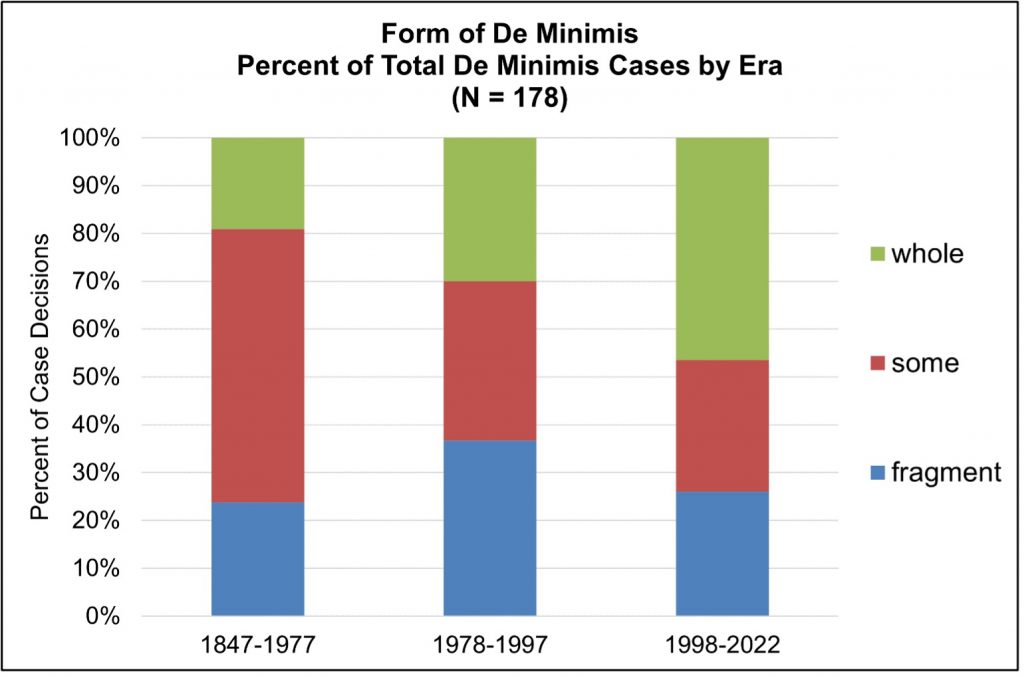

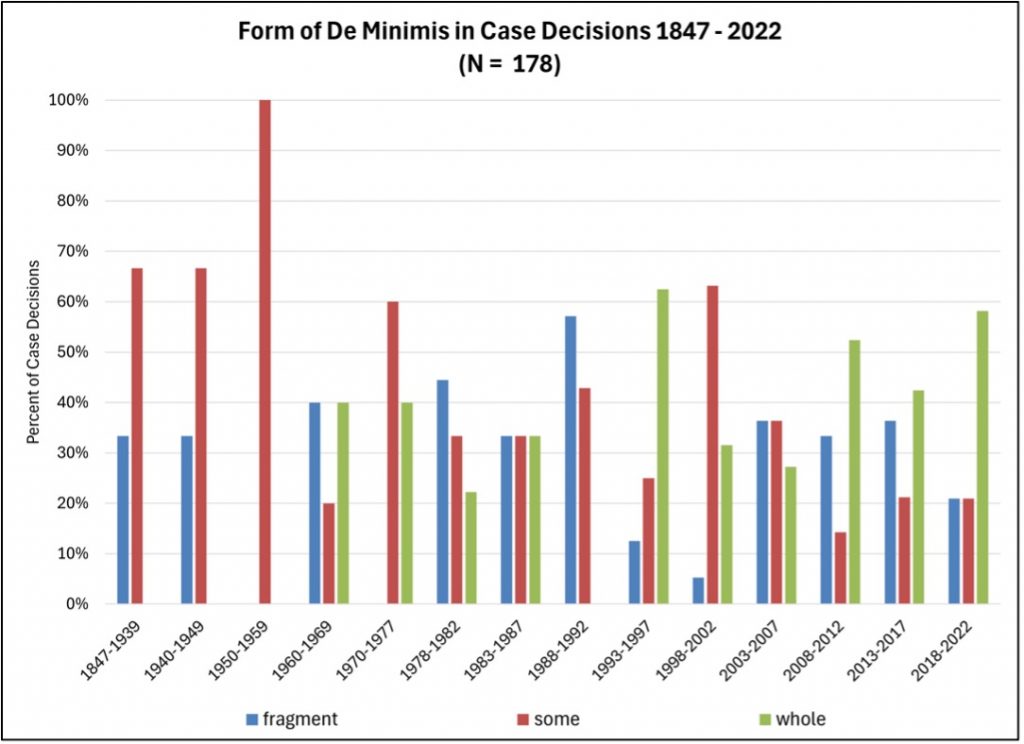

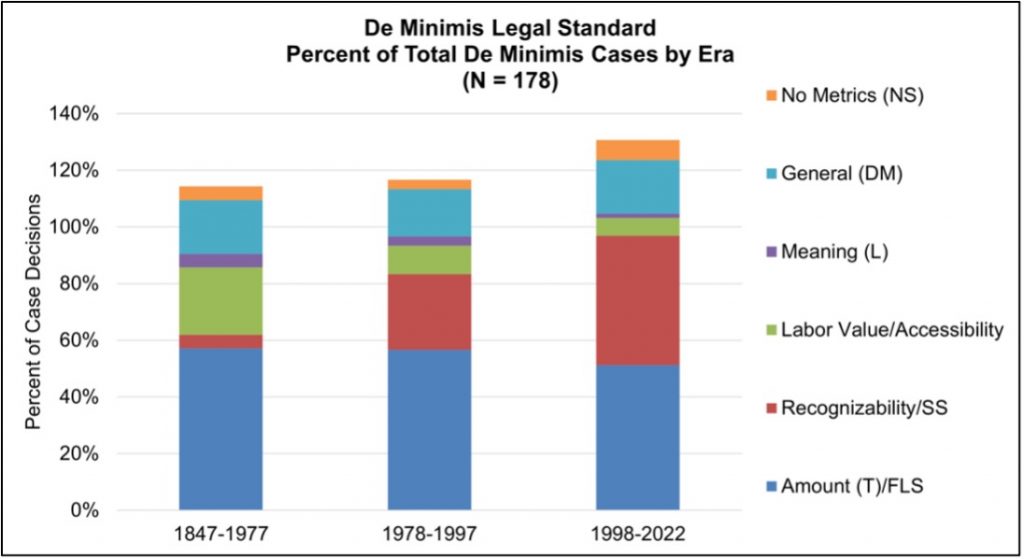

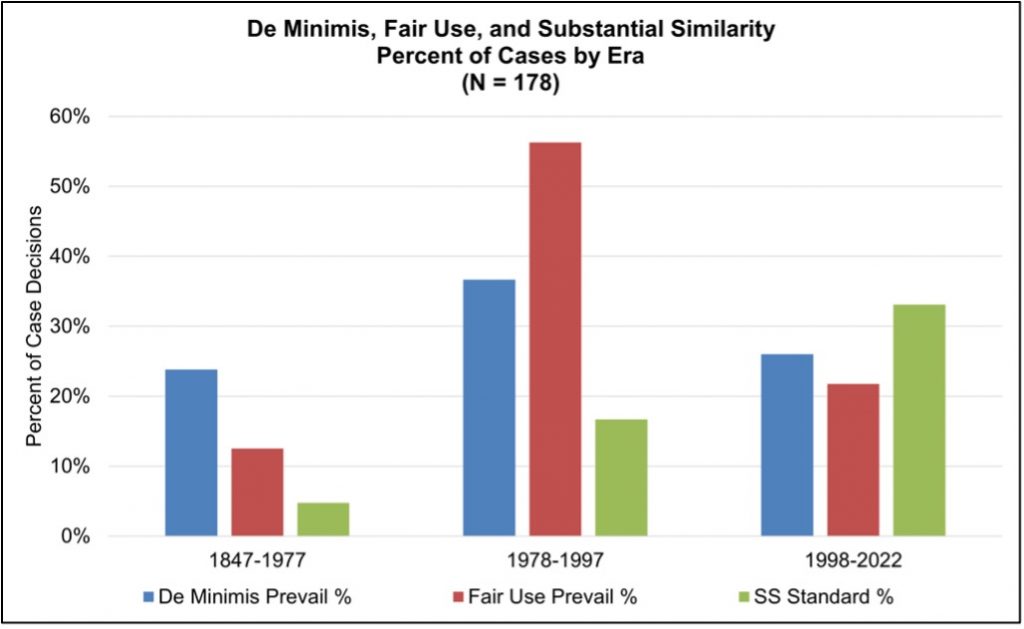

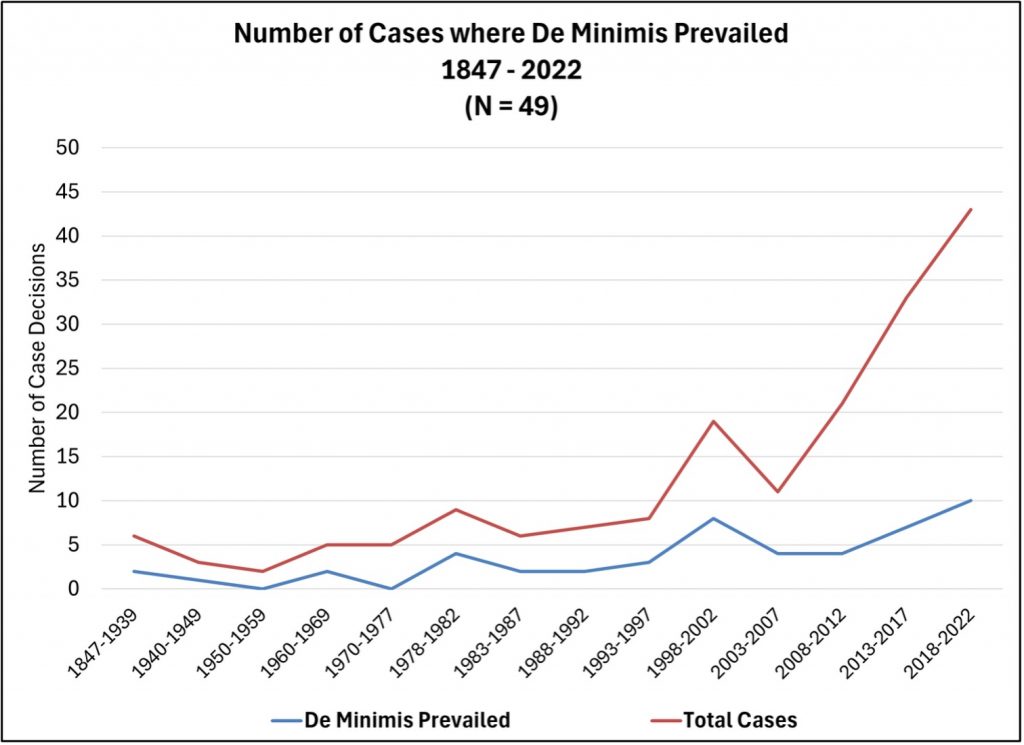

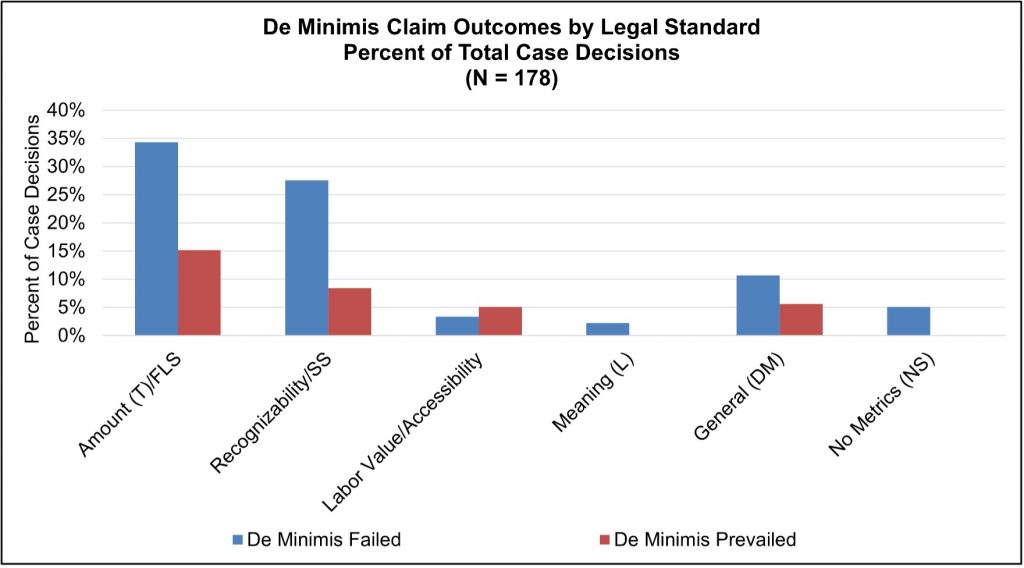

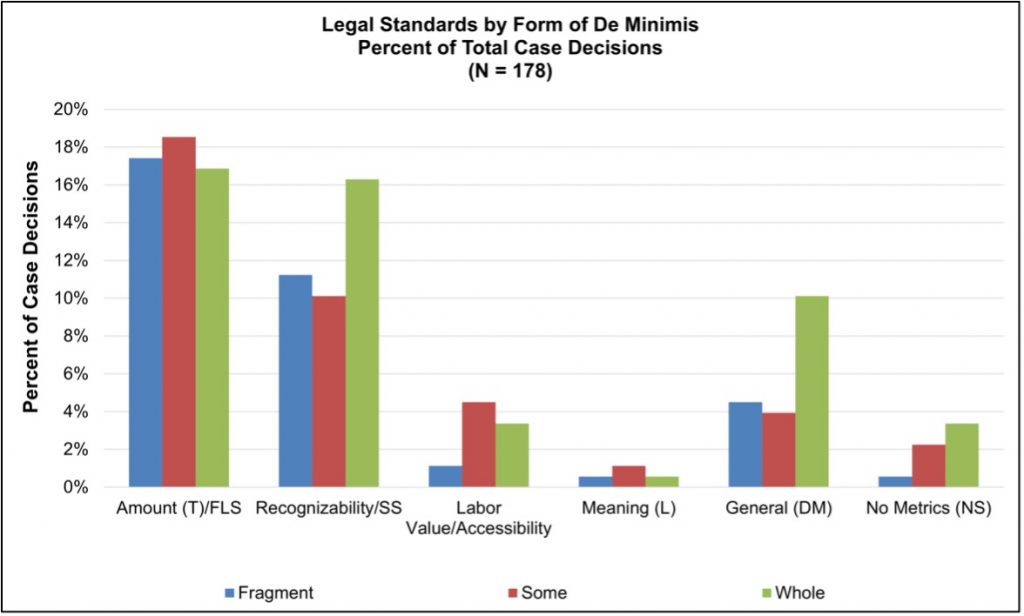

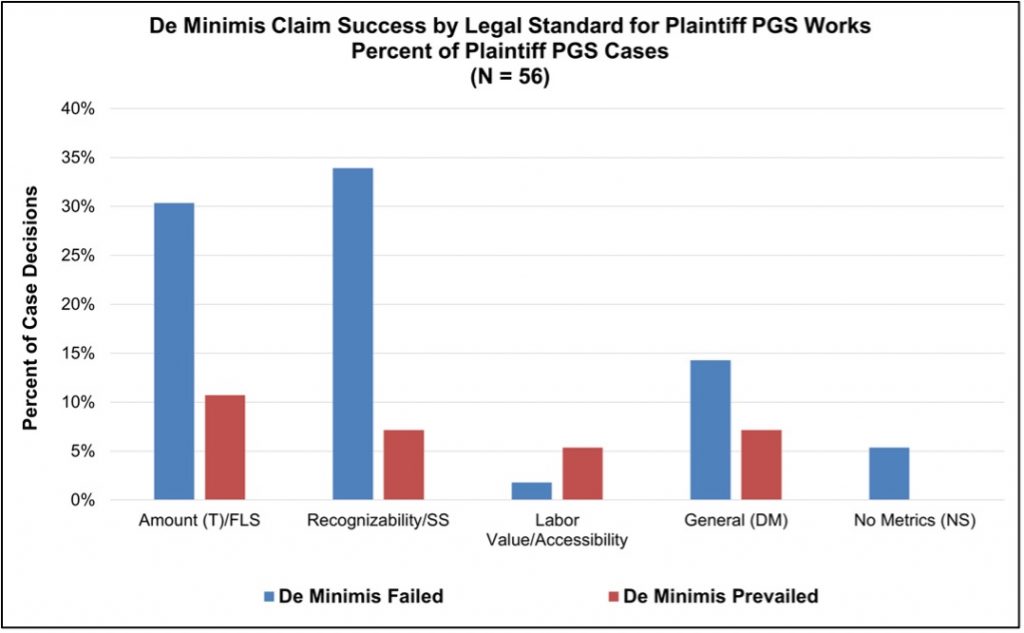

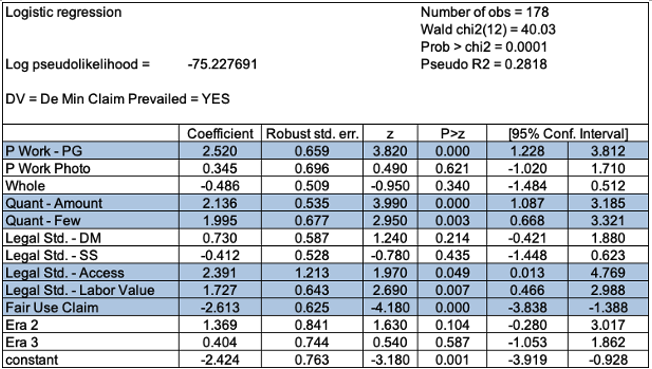

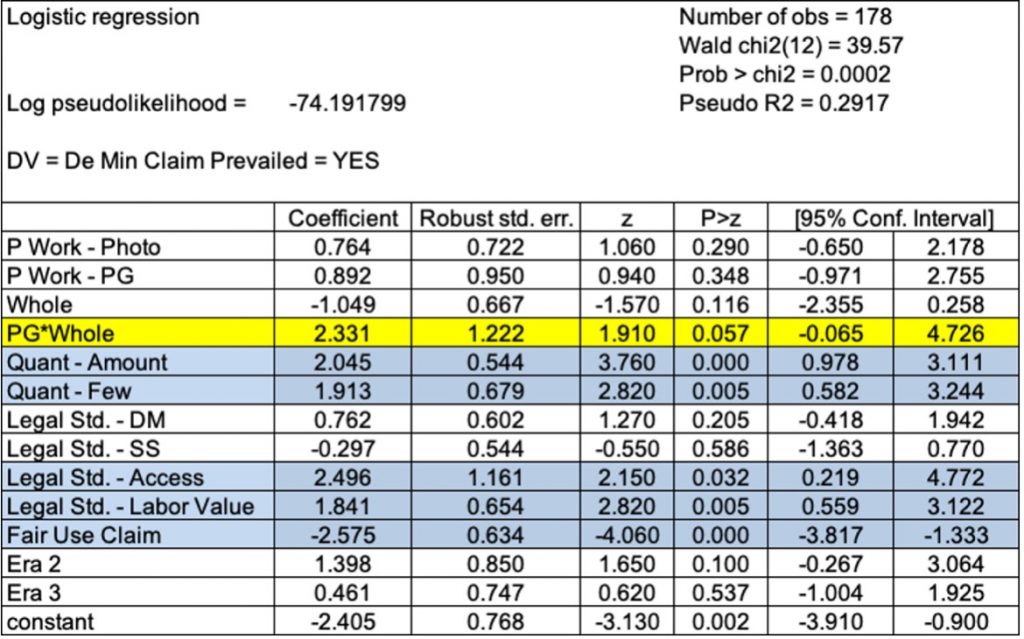

Our comprehensive dataset of de minimis cases between 1847 and 2022 includes only 178 court opinions. (We discuss the collection and coding of these cases in Part III.) At first, we were surprised by this small number. But in the context of assessing the contested evaluation of a “trifle,” finding 178 examples is significant.

As already mentioned, the earliest de minimis case is Webb v. Powers from the District of Massachusetts in 1847.79 After that, the de minimis defense does not occur with any regularity until the new century.80 In 1903, copyright’s originality doctrine expands to assure that more works are covered by copyright protection.81 And then the new 1909 Copyright Act further broadens copyrightable subject matter, scope, and remedies by adding a new statutory damage regime.82 Both events make exceptions and limitations to infringement even more important, which we believe roused the de minimis defense from its mid-19th century roots. As we describe below, this first Era contained twenty-one de minimis cases.

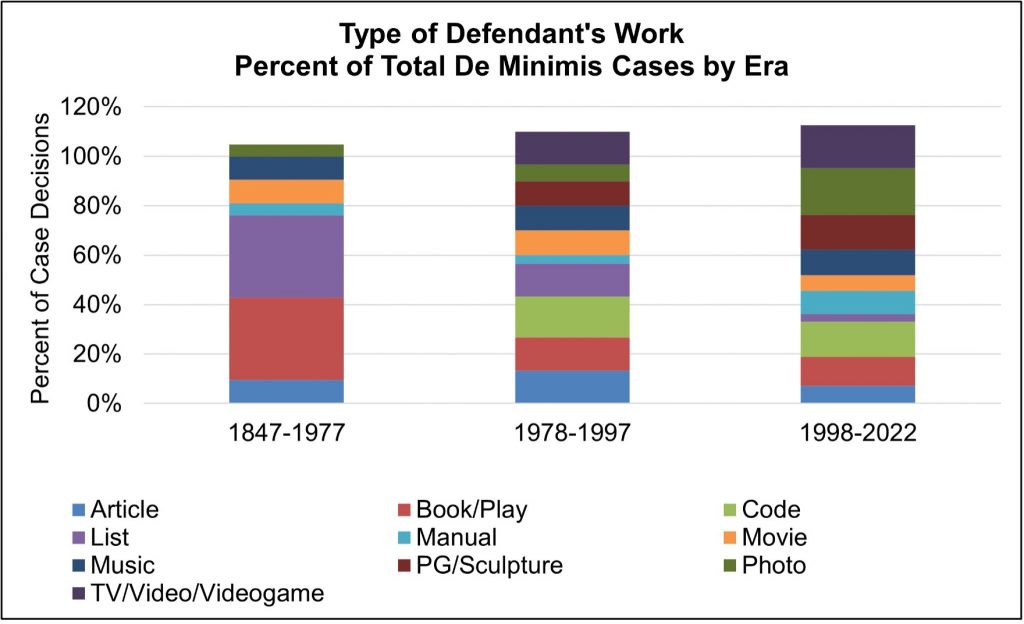

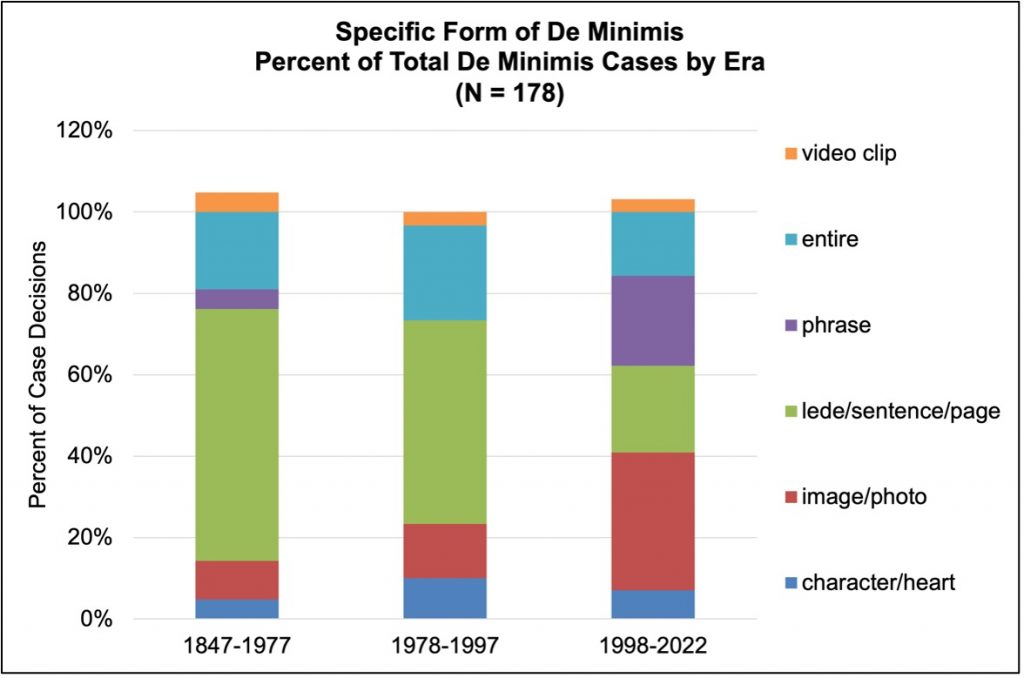

After the 1976 Act, defendants raise the de minimis defense with more frequency. Notably, fair use was codified in the 1976 Act, but the de minimis defense was not. Nonetheless, the variety and quantity of cases alleging de minimis copying as a defense to infringement rose substantially after 1978 to 157 cases, affirming its common law roots and its significance to court cases.83 Several features of a changing society fuel this upward trend of de minimis cases. First, unauthorized copying becomes ubiquitous with copying technology commercialized and accessible (think photocopy machines, home recording technology, and the rise of personal computers).84 Second, the entertainment industry’s licensing and distribution systems become sophisticated and complex, and freelance and independent authors are asserting copyright claims.85 Third, mid-20th century infringement standards evolve, including the doctrines of fragmented literal similarity and substantial similarity, allowing for reproduction infringement based on much smaller parts of the whole work.86 These technological and industry changes, combined with infringement doctrines evolving to become notoriously complex and quixotic,87 create the need for a more robust de minimis defense, which is asserted with more frequency in the Third Era.

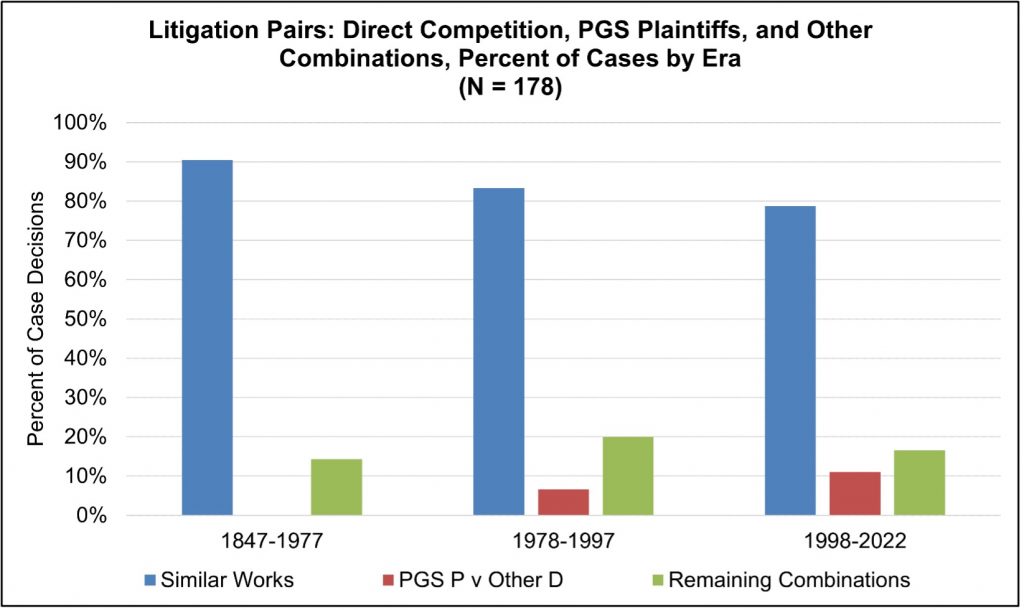

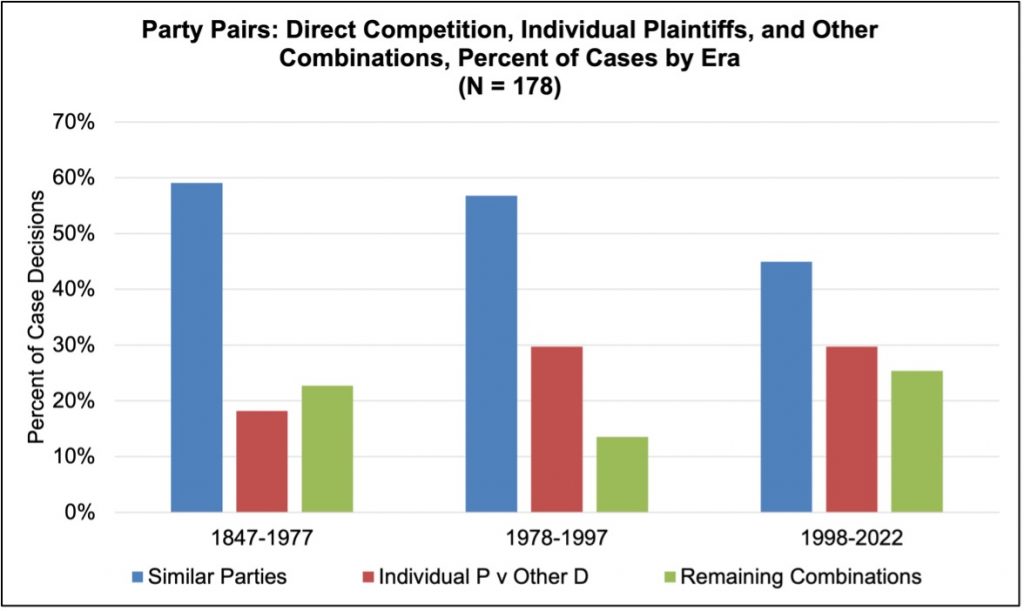

In this part, we divide the cases into Eras related to these trends and legal milestones. Within each Era, we discuss patterns in the parties’ identities, works, and the legal standards. A noticeable trend is that in the Early Era cases are between competitors and the works at issue arguably compete in the same market (e.g., book publisher suing another book publisher). By Era Three, however, the disputes are less often between parties offering arguable market substitutes, and instead they are between putative licensees and licensors (e.g., a visual artist suing a television company for hanging art in the background of a television show set). This later breed of lawsuit includes plaintiff complaining of defendant’s failure to license plaintiff’s work (or a part of it) as an input into defendant’s work, even when the requirement to pay remains debatable under copyright law. This new claim for copyright harm–not clearly market substitution, but instead the rise of a kind of in-licensing or rights/clearance practice–puts pressure on the de minimis defense, which immunizes fragmentary, partial, or fleeting copying of authored works. As we explain infra, the rise of this new kind of in-licensing claim harms the de minimis defense and too easily shifts the court’s attention to the more fact-intensive and costly fair use analysis. We urge a correction of this trend at the end of the Article with clearer de minimis guidelines and recommendations to litigants and courts.

A. The Early Era (until 1977)

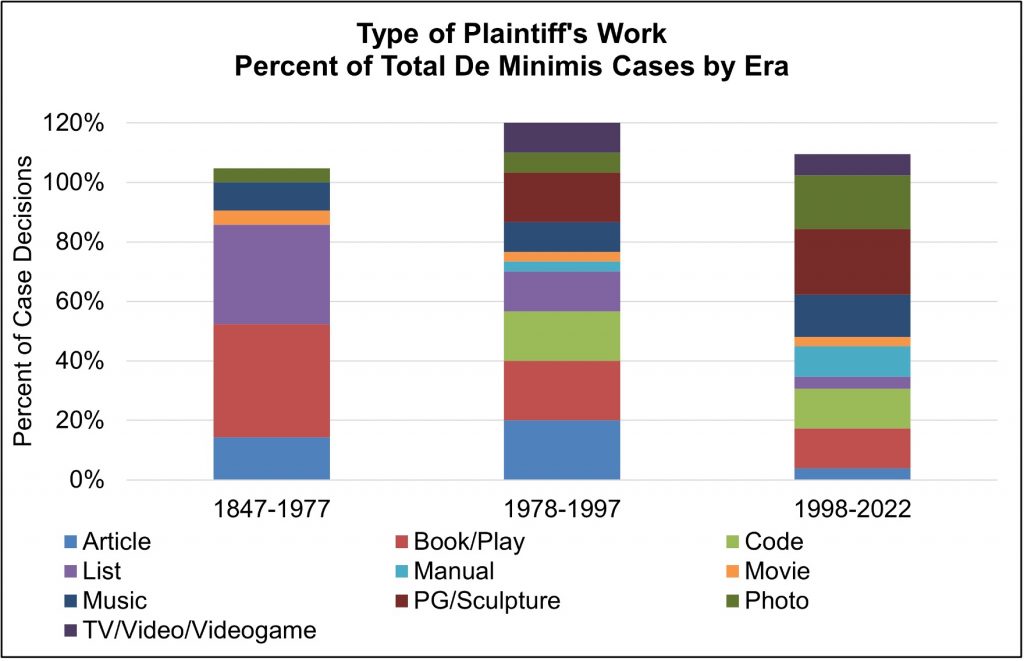

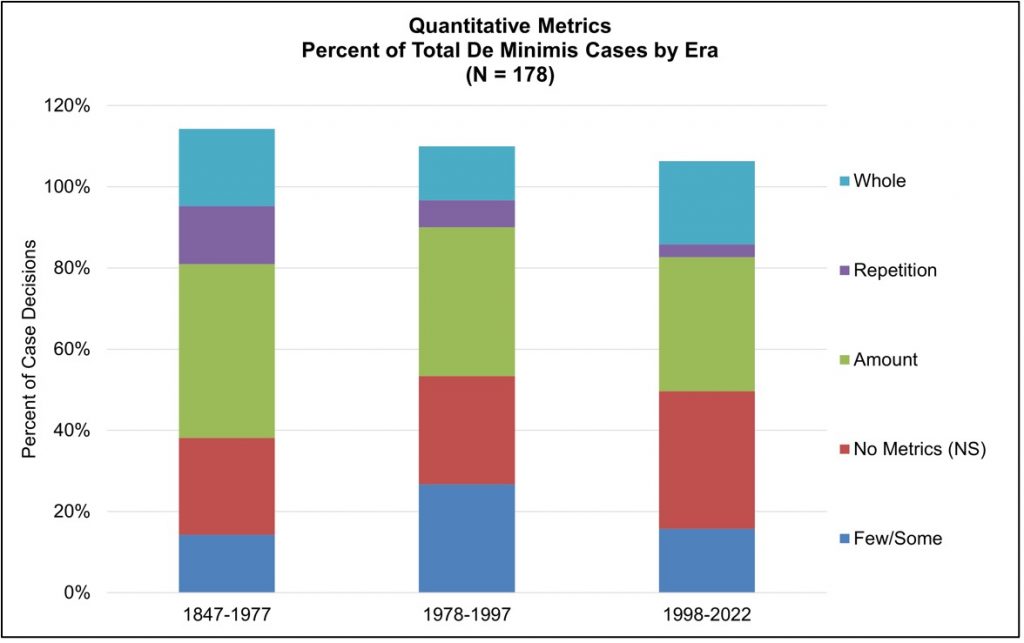

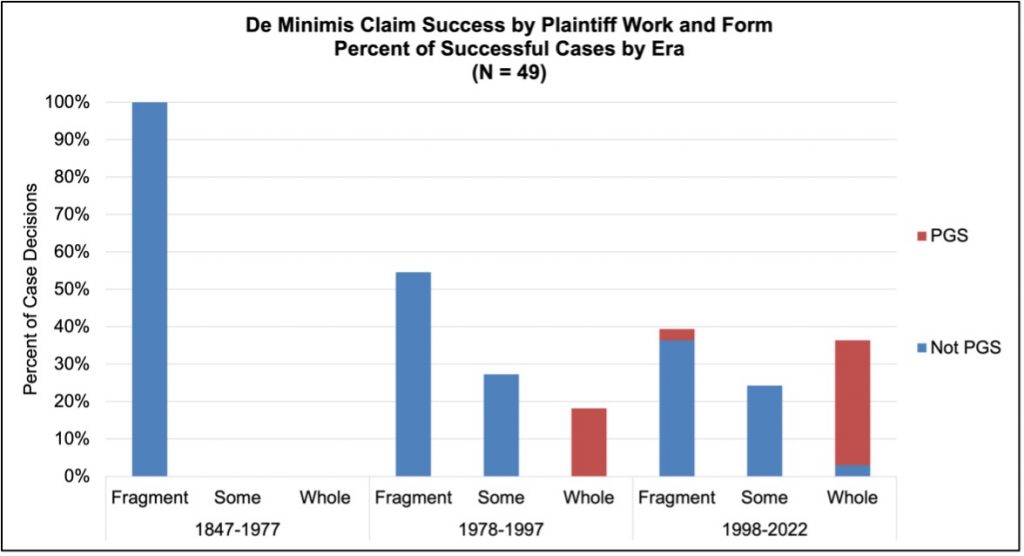

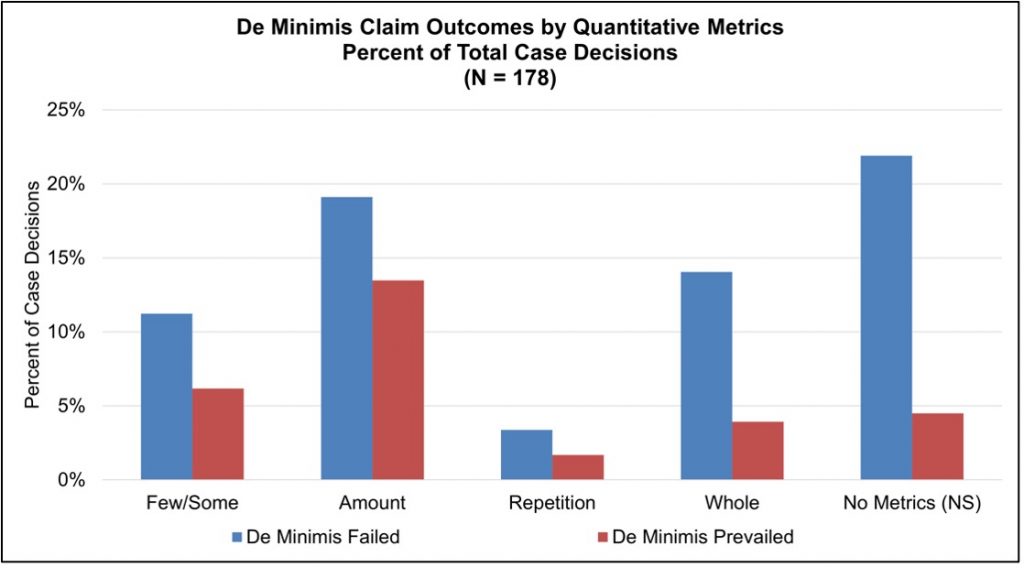

The Early Era, covering the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, contains only 21 cases. Of those, only 5 ended in a successful de minimis defense (including Webb v. Powers).88 The cases in the Early Era are largely between competitors in the same or closely related industries. They mostly concern directories, advertising catalogues, manuals and textbooks, high-information literary works of the technical or non-fiction kind. In all but four of the cases, copying is fragmentary or partial, and the court’s de minimis analysis while very brief features quantitative considerations.89 It makes sense that few de minimis cases arose in the first half of the 20th century, because copyright law still largely was thought to prohibit only copying of the whole work akin to market substitution.

When addressing defendant’s de minimis defense, the Early Era court often invokes a cursory standard with a single metric (usually quantitative) or no standard at all, and it simply says the use is or is not de minimis. Because most of these cases are fragmentary or partial copying cases, when the court finds infringement there is usually a determination that the copying has replaced the value of the original work in the marketplace. The substantial similarity standard for infringement was still developing into the one we recognize today, and it is rare in the Early Era for courts to use the phrase. Instead, courts say, for example, that “it is necessary that a substantial part of the copyrighted work be taken”90 or the copying was “not substantial” or “important.”91

One such case, Mathews Conveyor Co. v. Palmer-Bee Co. (1943), is a dispute between competing manufacturing companies in which Plaintiff alleged a range of contract and unfair competition claims.92 The copyright claim concerns their respective catalogues and occupies only a small part of a much larger opinion devoted to discussing the agency and contract relationship between the parties.93 Defendant allegedly reproduced as sketches several photographs from Plaintiff’s catalogue.94 The court described the defendant’s catalogue sketches of machine parts and materials as not being exact copies and being from different angles than the plaintiff’s catalogue photographs.95 Also, the status of plaintiff’s copyright was disputed because the catalogue appeared to be distributed without notice of copyright.96

Notwithstanding these weaknesses in plaintiff’s case, the Court of Appeals went on to decide

“the issue on this phase of the case…from a consideration whether there has been such a substantial infringement of plaintiff’s right…[and] that in order to sustain an action for infringement of copyright, a substantial copy of the whole, or a material part, must be reproduced.”97

As to the de minimis defense, the court said “on the principle of de minimis non curat lex, it is necessary that a substantial part of the copyrighted work be taken.”98 It cites Folsom v. Marsh for the proposition that “whether so much has been taken as would sensibly diminish the value of the original” is also a factor.99 The court then affirms the denial of Plaintiff’s copyright infringement claim, citing several reasons, including “that any injury to the plaintiff from defendant’s action in regard to these two sketches…is obviously infinitesimal; and that the alleged appropriation of the idea or form or perspective of plaintiff’s two cuts from among the hundreds in its catalogue, is insubstantial as an infringement of plaintiff’s copyrighted book.”100

We see in Mathews the characteristic feature of competitors fighting over market share and harnessing dubious copyright claims to do so. In this case, the court conceives of copyright infringement as a cause of action that prevents injury to the value of the work as a whole and does not consider the individual parts of the work (here photographs made into sketches) as separate from the catalogue.101 It further assesses the reproduction of two of the photographs into sketches as “insubstantial” and any injury suffered as “infinitesimal.”102 The de minimis analysis, infringement assessment, and fair use question reinforce each other, and also reinforce the conclusion of no copyright liability, but they are nonetheless described as distinct.

Another case from this era, Advertisers Exchange v. Hinckley (1951), involved a contract dispute between industry players in advertising.103 Plaintiff provided copyrighted advertisements to defendant-advertiser for redistribution in local papers in a select geographic area for a fixed annual fee.104 Defendant purportedly cancelled the contract with Plaintiff but continued to use the copyrighted materials (twenty-nine advertisements) for more than eighteen months thereafter in a local newspaper with a circulation of 3,261 copies.105 The court spends almost no part of the opinion deciding the issue of de minimis raised by the defendant. The extent of its ruling on that matter is this: “Compared to the amount which had been sent to the defendant from which he might choose such as he desired to use, it is true the amount was small, but it was important, and I think a substantial part of the material was used by defendant over this period of approximately 20 months.”106

Most of the opinion discusses whether the contract was in fact terminated and if so, what the damages should be. As to the latter issue, the court questions whether copyright or contract damages makes sense. A calculation of copyright damages “runs into a ridiculous amount,” the court says, and “it never was intended that the statute should apply in a case of this kind.”107 Because the contract was for services—the provision of advertising copy for a fixed annual sum no matter how much advertising copy the defendant used—the court rejected the idea of per-copy damages.108 “The only actual damages the plaintiff could possibly have suffered would be the loss of the sale of service to some other merchant in the community, which amounted to $156 a year, under the terms of the contract.”109

We see in Hinckley, as in Mathews, industry siblings with arm’s-length agreements in place. When the relationship breaks down, the plaintiff tries to use copyright law (which is arguably a marginal aspect of the business relationship) to recover damages from what is an obvious breach by the defendant of contractual terms. As in Mathews, the Hinckley court focuses on quantitative metrics to assess whether the copying is de minimis because, while each of the advertisements were copied as a whole, the amount of time the advertisements circulated was considered central to Plaintiff’s injury. The works are copyrightable literary works with pictorial components, and yet the court assesses the harm from copying in terms of lost contract revenue, substantially mitigating the damages under copyright law that would have been substantially higher given the statutory damages regime. This mitigation perhaps reflects the “small” number of unauthorized copies relative to the amount to which Defendant had access under the contract, counterbalanced by the “importance” of the unauthorized copies relative to the parties’ relationship and the duration Defendant continued to use the advertisements after terminating the contract. Unlike Mathews, Hinckley contains discussion of neither the infringement standard nor fair use. When the Defendant raises the de minimis defense in response to the Plaintiff’s copyright claim, the court simply says that the Defendant’s actions are not de minimis.110 Instead of assessing copyright damages, the court rewards the plaintiff under the contract, indicating sub silentio that the plaintiff’s injury only tangentially relates to unauthorized copying.111

In these cases, courts accept the fact of unauthorized copying of copyrightable material and assess whether that copying crossed a threshold of harm that copyright law aims to prevent. That harm appears to be the expected investment in the material and/or the value of the material copied measured by the context of the overall business transaction. The pithy de minimis discussion in light of the lengthier descriptions of the business transactions reflects the courts’ appreciation of the relevance of the parties’ business relationship to assessing harm from copying of the business materials. We think it fair to characterize these as competition cases in which de minimis relates to the extent of unfairness of the copying (but not the copying itself) and whether the copying interfered with the plaintiff’s business expectations. Whether we call these examples of copying “technical violations”—copying without cognizable harms—or copying that does not meet the quantitative threshold for infringement is reasonably debatable. But neither of these cases (and most cases in this era) do not evaluate infringement in a manner that resembles the substantial similarity analysis we have come to know.112 Nonetheless, the cases from this Early Era anchor the common law de minimis defense in copying that is unrelated to, or has so insubstantial an effect on, the plaintiff’s business interests.

B. The Transition Era (1978-1997)

The second era covers the first two decades of the 1976 Act. It contains thirty cases, of which eleven ended in successful de minimis defenses (only three of which also involved fair use, a feature of this Era we discuss infra in Part III). All but one of those prevailing defendant cases concerned copying of literary works.113 The number of de minimis cases in this era rises slightly as a percentage of all copyright case decisions (from 2% to 4%), but defendant win rates remains relatively the same.114 Distinct from the Early Era, the Transition Era included literary works encompassing both fictional and non-fictional works, as well as software cases for the first time. Like the Early Era, most litigation pairs in the Transition Era are parties in the same or similar fields, and cases brought to prevent industry competition.115

A difference in the Transition Era and the Early Era concerns the nature of the industries and the amount of the copying. As to the industries, in this second era, we see cases disputing the copying of software.116 And there are more entertainment companies, including television, music, and film as both plaintiff and defendant.117 As to the amount of copying, this era introduces defendants copying plaintiffs’ works in whole for inclusion in different works, not just parts of plaintiff’s works, such as a plaintiff’s sculpture in a film118 and plaintiffs’ photographs as part of an internet distribution service.119 Thus, the Transition Era appears to inaugurate the potential for in-licensing whole works as parts of other works.120 Newer copyright-rich businesses are more prevalent in this era.121

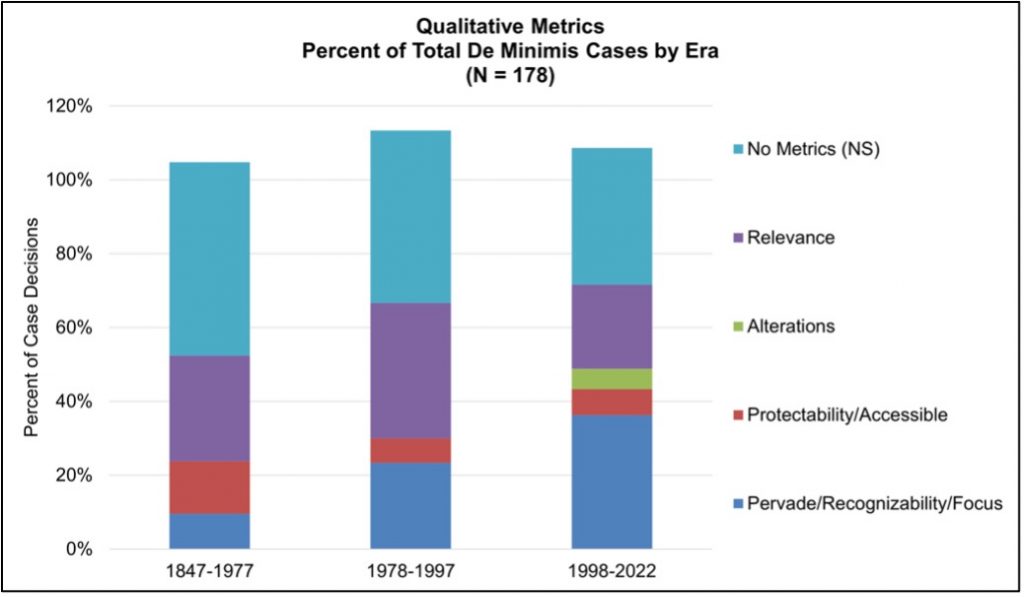

This Transition Era also inaugurates more case variation as between plaintiffs and defendants, size of the copying, and the legal standards courts employ to evaluate the de minimis defense. Quantitative metrics still predominate as they did in the Early Era, but in this second era courts more frequently employ a standard that approximates fragmented literal similarity to assess whether the defendant’s copying of the plaintiff’s work is either de minimis or constitutes a cognizable copyright harm.122 As in the first era, there are many cases in which the standard is conclusory, and the court simply accepts or rejects a finding of “de minimis non curat lex.” But in contrast to the first era, this second era contains cases in which courts evoke “recognizability” and “substantial similarity” as relevant to the de minimis assessment. These more fact-intensive and plaintiff-friendly analyses become common touchpoints for the infringement standard in the third (and contemporary) era and, we argue, unnecessarily complicate the de minimis defense, rendering it less able to achieve its purpose of judicial economy.

This is a Transition Era because we surmise that when media companies diversify, contributors to those media companies vie for market share in the value of the distributed content, and newer media companies and networks compete with older and more established ones.123 As copyright industries diversify, and more copyright authors claim a share of the revenue, courts struggle to determine when the defendant’s copying is trivial in relation to the parties’ business as a going concern and when, in contrast, copyright law should protect the plaintiff’s investment in their work by forcing defendant to pay or refrain from its use. Two illustrative cases follow in which the court correctly held the defendant’s use was defensible but not necessarily because it was de minimis. Both cases contain seeds of the doctrine’s unfortunate complexification, which sprout in the Third Era.

Computer Associates International v. Altai Inc. is well-known for its implementation of the “abstract-filtration-comparison” test for copyright infringement of computer software.124 The case “deals with the challenging question of whether and to what extent the `non-literal’ aspects of a computer program…are protected by copyright.”125 The court mentions the de minimis defense exactly once: in the context of approving the district court’s infringement analysis (using a fragmented literal similarity test) when comparing the competing programs’ parameter lists and macros as part of a fragmented literal similarity test. The court writes:

[F]unctional elements and elements taken from the public domain do not qualify for copyright protection. With respect to the few remaining parameter lists and macros, the district court could reasonably conclude that they did not warrant a finding of infringement given their relative contribution to the overall program. See Warner Bros., Inc. v. American Broadcasting Cos., Inc.,720 F. 2d. 231, 242 (2d Cir. 1983) (discussing de minimis exception which allows for literal copying of a small and usually insignificant portion of the plaintiff’s work); 3 Nimmer § 13.03[F][5], at 13–74.126

In support of the non-infringement determination, the court cites a case and a treatise, both confusingly relating the de minimis defense with the infringement standard.127 The court relies on Nimmer for his discussion of the fragmented literal similarity test, occurring when copying is exact but not comprehensive.128 Exact copying of small portions of a copyrighted work should be de minimis, but not when the copying is extensive. Nimmer’s discussion of fragmented literal similarity, and the cases adopting it, is a major step toward what Oren Bracha has called the doctrinal “slippery slope,” whereby de minimis (as measured in small bits) becomes part of the substantial similarity test for infringement (as measured both quantitatively and qualitatively).129 The court also cites Warner Brothers v. ABC, a case from this same time period when plaintiff film company unsuccessfully alleged infringement by defendant television company of Superman (the character) in the new television show “The Greatest American Hero.”130 The defendant evoked the de minimis defense as part of a fragmented literal similarity test to support its argument that only a small part of a large work was copied (a character) and arguably only an idea (of a superhero).131 The appellate court in Computer Associates, applying this precedent, approved the district court’s finding of no infringement, saying “the district court reasonably found that [plaintiff] failed to meet its burden of proof on whether the macros and parameter lists at issue were substantially similar.”132 Here, we see the use of fragmented literal similarity test evolving to bridge the de minimis defense with the infringement standard, melding quantitative and qualitative evaluations into a broader substantial similarity analysis.133 This move arguably guides courts to decide de minimis cases when quantitative metrics are objectively discernible and the use of the small bits are insubstantial parts of the plaintiff’s work. This is a laudable and clear baseline standard for a de minimis defense on a motion to dismiss, and one we take up at the end of this Article. It nevertheless gets marginalized as the de minimis doctrine evolves to appear entangled with more complicated infringement standards (as it does in this case) and more frequent fair use defenses.

Computer Associates retains some features of the Early Era. It maintains a quantitative focus on the nature of the copying and describes a competitive situation between parties whose literary works – computer software – are thinly protected by copyright but are nonetheless valuable products for sale. The de minimis analysis in Computer Associates bridges the earlier cases, in which discrete amounts of copying were measurable as against copying of the whole work, with the newer cases in which valuable but small parts of the work are being copied (literary characters or software macros). Computer Associates mentions the de minimis defense, fragmented literal similarity analysis, and the substantial similarity test all in one paragraph,134 evidencing the court’s struggle to determine when fractional but material copying is cognizable as an infringement or when it is otherwise defensible. The defendant-friendly holding makes good sense to us, and it is followed in future decades as significant precedent.135 But the de minimis aspect of the case is underappreciated and, we think, played an important role in the defendant’s success.

Carola Amsinck v. Columbia Pictures Industries Inc. presents another kind of transition case.136 It is not a case between competitors, but one in which a self-employed graphic artist, Carola Amsinck, sues a film company for its use of her whole copyright work (pastel-colored teddy bears) in several movie scenes.137 This case is thus a precursor to the claims in which parties dispute whether distinct copyrighted works (e.g., graphic art) incorporated as an input into larger and more complex copyrighted works (e.g., a film) is copyright infringement.138 Amsinck’s teddy bears were made, with her permission, into a baby mobile by a toy company.139 The company making the mobile credited Amsinck with the original design and paid her.140 But Defendant Columbia Pictures neither gave Amsinck credit nor licensed the work (as a toy or graphic art) for use in the film.141 The mobile appears in several scenes in the film for between two to twenty-one seconds, “with a total exposure of approximately one minute and thirty-six seconds.”142 The court describes the mobile as at times “barely visible” and at other times “in a close-up shot.”143

Defendant Columbia Pictures prevails in a combination ruling that the film was not a “copy” of the mobile in the way copyright cares about, and, in the alternative, because the film’s use of the copy was fair.144 As to the first point, the court concludes that Columbia Pictures did not commit substitutional copying, which is the kind copyright law aims to prevent.145 The court states that

[T]o establish `copying,’ the plaintiff must prove that the defendant `mechanically copied the plaintiff’s work’; there must be some degree of permanence or the maxim `de minimis‘ applies, requiring a finding of no liability. In determining whether a use constitutes a copy, the courts look to a functional test to see whether the use has `the intent or the effect of fulfilling the demand for the original.146

This invocation of de minimis resembles the cases from the Early Era in which courts found the defendant’s copying of parts of the plaintiff’s work to be trivial in the context of market substitution. The difference here is that the defendant is copying the whole of the plaintiff’s work and the court’s assessment of triviality relates to the minimal time the work appeared in the film and the lack of market for its filmed appearance. The court concludes that

[T]he defendants’ display of the Mobile bearing Amsinck’s work is different in nature from her copyrighted design. In this matter, the defendants’ use was not meant to supplant demand for Amsinck’s work; nor does the film have the effect of diminishing interest in Amsinck’s work. Defendant’s use was not a mechanical copy. Defendants’ use, which appears for only seconds at a time and can be seen only by viewing a film, is fleeting and impermanent. This Court therefore concludes that the defendants’ use is not a copy for the purposes of a copyright infringement action.147

This resembles the technical use defense that Judge Leval evokes in Davis v. Gap, Inc. when he describes the singing of Happy Birthday by restaurant patrons, quoted earlier.148 Whereas defendant (Columbia Pictures) used and enjoyed plaintiff’s work, defendant’s use and enjoyment are insignificant in light of the defendant’s work as a whole and as compared to how plaintiff (Amsinck) ordinarily earns a living from her copyrighted work (e.g., selling copies of the teddy bears or licensing copies of them to make mobiles). This court determines triviality, or the existence of a “trifle,” in terms of the non-existence or miniscule market harm to the plaintiff. It does not consider the use of the plaintiff’s derivative work in the film as a market on which the plaintiff reasonably relies, and even if it existed, the use was so fleeting or trivial to be inconsequential.

The court’s determination that the defendant did not engage in copyright infringement could have ended the case. But the court nonetheless also conducted a fair use analysis, possibly, to insulate its first ruling with a second in case of appeal.149 The fair use analysis starts with factor four and, essentially, repeats the conclusion from the first part of the opinion: “In situations where the copyright owner suffers no demonstrable harm from the use of the work, fair use overlaps with the legal doctrine of de minimis, requiring a finding of no liability for infringement.”150 The court explains that

The film does not pose a threat to the market for Amsinck’s work in either licensing artwork or in future sales to motion pictures. Indeed, the Court believes that, notwithstanding the lack of identification of the Mobile, its use in the film might actually increase the demand for mobiles in general, thereby benefitting plaintiff indirectly.151

From this statement, we learn the court does not consider the parties to be competitors in related markets; it considers the defendant’s use of the plaintiff’s work as beyond the reasonable or customary use that would require payment.152 The court’s analysis of the third fair use factor (amount and substantiality) similarly repeats its earlier de minimis analysis.153 While conceding that the defendant displays the design “in its entirety” and “used every element of the work,” the court explains, “the Mobile is seen for only a few seconds at a time, and the artwork itself is visible for less than 96 seconds.”154 The court concludes that “[a]lthough generally a use does not constitute fair use if it reproduces the entire work, the Court declines to find that the defendants’ short-term display of the Mobile in a film precludes a finding of fair use.”155

The court’s quantitative analysis (the amount of time the works was visible in the film) combined with an assessment of market harm as a measure of whether the use was de minimis resembles earlier cases about partial copying and market substitution. It also resembles later cases discussed infra in the Contemporary Era insofar as: the copying is whole (however brief); the parties are not competitors; and the plaintiff’s work is an input to the defendant’s work, albeit not in a central way (e.g., not in the manner of sequels or translations).156 Notably, however, the Amsinck court does not ask whether the defendant’s work is “substantially similar” to the plaintiff’s. Doing so would not make sense in this context. But the court does consider how visible the plaintiff’s work is to viewers and how much the defendant’s work focuses on the plaintiff’s work, resembling a “recognizability” evaluation that eventually (and unfortunately) becomes an alternative for “substantial similarity” in similar cases in the Contemporary Era.157 This case thus bridges the earlier era with the subsequent one, combining a quantitative and qualitative assessment, perhaps because of the rising frequency of whole copying.158 Fair use is also more helpful now that it has been expressly codified in the 1976 statute requiring analysis of market harm, purpose and character of the use, amount copied, and nature of the work.159

Despite the prolonged fair use analysis in the Amsinck case, it is a laudable decision that – although not decided on a motion to dismiss – reaches the right result for the right reasons. Quantitatively miniscule and qualitatively insignificant, the use of plaintiff’s derivative work in the background of a film is not copyright infringement. Notable is that this case is about the whole of a plaintiff’s work, not parts of it, and still the court determines that the copying is trivial. To be sure, judicial and lawyering resources were wasted deciding a case about such a triviality. Hopefully, the patterns and standards described in this Article can streamline cases like Amsinck and guide courts and defendants in the future.

As we describe more fully in Part III, after the 1976 Act and in the Transition and Contemporary Eras, de minimis cases include many more defendants arguing that whole copies are nonetheless de minimis.160 This may seem counterintuitive, but it’s an important evolution of the case law that should save more judicial and lawyering resources if followed. Only four such cases existed between 1960-1977, comprising 19% of the cases before 1978. Starting in 1978, and in this Transition Era, cases alleging whole copying in which the defendant raises a de minimis defense compromises 30% of the cases. This increase might be a result of earlier courts treating the “work” as a more fixed and less flexible category.161 As explained supra, in the first half of the 20th century and in the Early Era, parts of works copied and disputed as de minimis may have concerned photographs or sketches in catalogues or manuals, where the work was the catalogue and the part was the photograph or sketch contained within it.162 But in the second and third eras, a plaintiff might bring such a case for unauthorized copying of a photograph or a work of visual art (as in Amsinck) because that work is separately authored and owned.

The growing number of “whole” work de minimis cases after 1978 might also be a result of increased access to copying technology, the growing acceptance of copying whole works for personal use, ephemeral use, or as raw material for the rapidly evolving entertainment and high-technology industries.163 Whatever the reason for the rise of whole copying cases, they put pressure on the de minimis standard, which was primarily (although not always) concerned with small parts of works, not the inconsequential use of whole works. This pressure should be alleviated in light of the revealed patterns in these cases adjudicating whole copying as de minimis when uses are quantitatively small and qualitatively insignificant.

We consider both Computer Associates and Amsinck examples of early versions of what emerges in the Contemporary Era as a fragile basis for the de minimis defense, delineated by milestone case Ringgold v. Black Entertainment Television.164 As the next section explains, Ringgold describes and affirms both a “technical violation” (a whole copy without consequence) and “quantitative threshold” standard for the de minimis defense. The first is “a technical violation of a right so trivial that the law will not impose legal consequences”;165 and the second is copying that “has occurred to such a trivial extent as to fall below the quantitative threshold of substantial similarity.”166 Ringgold also includes a qualitative analysis of the use to which the copy is put as part of its description of the de minimis defense, which closely resembles a substantial similarity analysis.167 Before and during the Transition Era, the substantial similarity test was evolving and expanding. We believe this shift was partly because of the changing nature of the claims being brought by parties who demand licenses for a broad range of uses of their copyrighted works (e.g., Carole Amsinck). When plaintiffs bring infringement claims with more frequency of whole copying as background input into complex audiovisual works, the quantitative metric of the de minimis standard adjusts and the qualitative metric rises in significance. We discuss this trend, combining quantitative and qualitative metrics complexifying the de minimis defense in Parts II.C and III below.

C. The Contemporary Era (1998-2022)

The Contemporary Era differs in significant ways from both the Early and the Transition Eras. As Part III describes in more detail, there are many more cases in the Contemporary Era. Also, the rate of defendant successes declines (e.g., the de minimis defense is less successful overall). The third era is also characterized by more diversity: the identities of the litigants are more varied, plaintiff-authors appear more frequently to file opportunistic lawsuits for licensing revenue with questionable claims of market harm, and courts’ legal evaluations of de minimis are more varied and complex.

There are 127 cases in this era, which as a percent of all copyright decisions is more than double the previous eras.168 It might make sense, then, that legal standards would be more diverse as courts struggle to assess de minimis defenses across a wide range of claims and industries.169 Although the de minimis defense is more common in the Contemporary Era, it prevails less frequently as compared to the Transition Era.170

As in previous eras, this one includes competitors in industries not reasonably relying on copyright, who nonetheless harness copyright to contest certain business practices. These include financial services and manufacturing companies competing on sales of goods and services but who sue for, among other things, copying parts of catalogues or business materials.171 Copyright is largely a side-show in these cases in which trade secret misappropriation, tortious interference with contractual relations, and breach of fiduciary duty play more central roles.

Different from earlier eras, however, in the Contemporary Era, there are more music cases and many more software cases.172 This tracks the growth of both industries in the internet age and to us is unsurprising, especially when copying small parts of either music or software is easier with digital technology and bits of music or software are reasonably considered lawful input into new music or software. These cases become notorious and contested disputes, as the “value” of the bit copied (e.g., a musical riff or software code module) arguably has independent market significance. These features confound the de minimis doctrine, as we see in the discussion of VMG Salsoul v. Ciccone below.

The bulk of the cases in this era involve entertainment or media companies and distributors, and they are between individuals and companies or individuals and other individuals (e.g., not between competitors).173 The kind of copying now is fairly split between whole and partial (or fragmentary), with whole copying outpacing both in the latter part of this era between 2008-2022.174 Plaintiffs’ claims of whole copying of their pictorial/image-based works predominate in the Contemporary Era, and the landmark cases discussed below illustrate this trend. This is when the de minimis doctrine should be most useful, in the vein of Amsinck and Computer Associates, and yet its contours blur in tandem with the more complex infringement standards and fair use assessments that are also evolving.

Over half of the courts in cases of this third era employ either no evaluative standard or only a quantitative standard to determine whether the copying was de minimis.175 This is not surprising, because that is how de minimis started and it reflects the earlier eras. However, in the Contemporary Era, qualitative evaluations of de minimis become more common, with as many as 42 of the cases (a third) referring to “substantial similarity.”176 “Substantial similarity” often includes “recognizability” as part of the standard, which we think makes Plaintiff’s case easier to prove and contributes to the unfortunate weakening of the de minimis defense.

The Contemporary Era cases span a range of approaches reflecting this era’s diversity. Cases such as Ringgold v. Black Entertainment Television (1997),177 in which a visual artist plaintiff wins against a television company, and Gottlieb v. Paramount Pictures Corporation,178 in which a visual artist plaintiff loses against a film company, are different sides of the same coin. We discuss them below.179 These have come to be known as landmark cases in for the doctrine.180 But whatever their milestone status, their doctrinal approach to de minimis, including qualitative evaluations that resemble aesthetic assessments, remains a minority approach. A contrasting case, the music sampling dispute VMG Salsoul v. Ciccone, reflects approaches from earlier eras assessing fragmentary copying in quantitative terms and elevates the de minimis standard in a way that would effectuate judicial economy and copyright policy if decided on a motion to dismiss.181 As discussed below, the defendant’s win in VMG aligns with the trends in the earlier eras and continues in this contemporary era to maintain the vitality of the de minimis defense.

Finally, the case of Bell v. Wilmott Storage Services (2021), rejecting a de minimis defense for whole copying of a photograph on an obscure website, is an outlier and, we argue, incorrect. But it is nonetheless significant.182 Plaintiff prevails in Wilmott for what in earlier eras would be a technical violation of copyright (a whole copy without harmful effect). Defendant’s display of plaintiff’s photo on a hard-to-access website inflicted no market harm.183 Courts in earlier eras would likely have dismissed as de minimis the single use of a photograph in an undistributed (or not widely distributed) publication to avoid wasting judicial resources.184 That the plaintiff-photographer prevails in Bell v. Wilmott is unfortunate and a mistake. The court’s reasoning in Wilmott relies in part on the absence of de minimis in the statute’s text, and thus is a head-in-the-sand formalistic reading of copyright’s scope defying the century’s long history of the common law de minimis defense.185 Wilmot is also inconsistent with many of the cases in this era of whole copying which result in a relatively high number of defense wins. As we explain more fully in Parts III and IV, this contemporary era’s increasing tolerance for whole copying of pictorial works, contra Wilmot, inaugurates an updated and laudable version of the quantitatively minimal copying standard from prior eras. In this Contemporary Era, the quantitative analysis applies consistently to whole works when used for a short time and with insufficient visibility.186 If courts in the future fail to follow this trend and instead rely on Bell v. Wilmot, something we do not advocate, the de minimis doctrine is likely to become less helpful to defendants and courts, frustrating the principle of judicial economy that it serves.

1. Ringgold and the Second Circuit Cases

Ringgold is a dispute about the unauthorized display of a “story quilt” (in poster form) as background set decoration for a television show.187 (See Image 1.) The poster of the quilt was displayed intermittently during the half-hour sitcom for a total of 27 seconds.188 The court nonetheless held that that use of the poster was not de minimis and violated Faith Ringgold’s copyright in the quilt. The court also rejected fair use as a defense.189

The Ringgold court recognized that a “copyrighted work might be copied as a factual matter, yet a serious dispute might remain as to whether the copying that occurred was actionable.”190 Notably, Ringgold described three possible invocations of de minimis as a defense to copyright infringement: (1) “a technical violation of a right so trivial that the law will not impose legal consequences”; (2) copying that “has occurred to such a trivial extent as to fall below the quantitative threshold of substantial similarity, which is always a required element of actionable copying”; and (3) as part of the fair use analysis to assess its third factor, “the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole.”191

This tripartite division of the copyright de minimis defense is a fair reading of its history across the eras. The Ringgold court explains that the first category of “technical violations” is “rarely litigated” because of their very nature.192 In support, it references Judge Pierre Leval’s 1997 Nimmer Lecture (reproduced in his opinion in Davis v. Gap, Inc. and quoted supra) in which he explains that singing “Happy Birthday” in a restaurant or making a photocopy of a cartoon to hang on the refrigerator are examples of “de minimis non curat lex.”193 The Ringgold court also cites its Knickerbocker Toy Co. v. Azrak-Hamway Int’l Inc. decision.194 In that case, the court dismissed the plaintiff’s copyright infringement claim on the basis of a technical but trivial violation in which an office copy of the plaintiff’s work was made but never widely distributed, concluding the harm from the unauthorized copying was so small that legal enforcement was not justified.195

Ringgold‘s main contribution to copyright law is its application of the second category of the copyright de minimis defense, which it uses to analyze the sitcom’s use of the story quilt. In considering whether the second kind of de minimis use prevails as a defense, Ringgold applies a standard that copying of protected material must “fall below the quantitative threshold of substantial similarity.”196 The court says this necessitates looking “to the amount of the copyrighted work that was copied, as well as (in cases involving visual works), the observability of the copyrighted works in the allegedly infringing work.”197 Observability demands consideration of factors such as “length of time the copied work is observable…and such factors as focus, lighting, camera angles, and prominence.”198

Applying this standard, the court engages in an aesthetic interpretation of the sitcom to reject a de minimis defense. The court assesses the television show’s use of the story quilt – how the show displayed the story quilt (prominently and in focus) and the role the quilt played in the sitcom’s story (affirming themes and deepening character delineation). It describes a 4-5 second segment in which its “own inspection of a tape of the program reveals that some aspects of observability are not fairly in dispute.”199 In this description, the court discusses camera angle, position of actors in relation to the quilt, scene framing, and camera focus. It concludes, saying

An observer can see that what is hung is some form of artwork, depicting a group of African-American adults and children with a pond in the background. The brevity of the segment and the lack of perfect focus preclude identification of the details of the work, but the two-dimensional aspect of the figures and the bold colors are seen in sufficient clarity to suggest a work somewhat in the style of Grandma Moses….All the other segments are of lesser duration and/or contain smaller and less distinct portions of the poster. However, their repetitive effect somewhat reenforces the visual effect of the observable four-to-five second segment just described.200

Based on this quantitative and qualitative analysis of the sitcom’s use of the quilt, the court determines that the quilt is “recognizable,… and with sufficient observable detail for the `average lay observer’ to discern African-Americans in Ringgold’s colorful, virtually two-dimensional style. The de minimis threshold for actionable copying of protected expression has been crossed.”201 Finding no de minimis use and substantial similarity, the court then also rejects the defense of fair use, concluding the balance of the factors favors the plaintiff despite the defendant prevailing on factor three.202 Ringgold‘s effect is that later cases also conduct this layered aesthetic analysis by folding the de minimis defense into the infringement assessment as a component of the substantial similarity test, grounding copyright misappropriation in recognizability by the “average lay observer.”203

The Ringgold test, while plaintiff-friendly, does not inevitably result in a defense loss. A year after Ringgold, the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit decides Sandoval v. New Line Cinema Corp, a case raising a similar circumstance as Ringgold.204 In Sandoval, plaintiff photographer Jorge Antonio Sandoval disputes the use of ten of his photographs by New Line Cinema in the background of the film “Seven.”205 The photographs were used in the full-length film and “visible, in whole or in part, for a total of approximately 35.6 seconds.”206 The court cites Ringgold for the applicable de minimis standard: whether “the copying of the protected material is so trivial as to fall below the quantitative threshold of substantial similarity, which is always a required element of actionable copying.”207 As in Ringgold, the court closely analyzes the use of the photographs, describing their observability and contextualization in the film. In the court’s description,

[T]he photographs never appear in focus, and except for two of the shots, are seen in the distant background, often obstructed from view by one of the actors,…figures in the photographs are barely discernable, with one shot lasting for four seconds and the other for two seconds. Moreover, in one of the shots, after one and a half seconds, the photograph is completely obstructed by a prop in the scene.208

As in Ringgold, the Sandoval court reviews video evidence, becoming a kind of film critic.209 But unlike in Ringgold where plaintiff prevails, in Sandoval the plaintiff loses. The Court of Appeals affirms the district court’s grant of summary judgment for the defendant, finding “that the defendant’s copying of Sandoval’s photographs falls below the quantitative threshold of substantial similarity….[b]ecause Sandoval’s photographs appear fleetingly and are obscured, severely out of focus, and virtually unidentifiable, we find the use of those photographs to be de minimis.”210

Notice how in both Ringgold and Sandoval, defendants copied all of the plaintiff’s work – the whole quilt and each photograph. Defendants’ copying was neither fragmentary nor partial. These cases are thus unlike those from previous eras that contest the harmful uses of fragments or parts (sentences or sketches) that compromise pieces of a larger whole. Nonetheless, these courts evaluate the whole copying of pictorial works under a de minimis standard as either “a technical violation of a right so trivial that the law will not impose legal consequences” or as quantitatively trivial and qualitatively insignificant.211 In both Ringgold and Sandoval – as in Carola Amsinck – the defendant’s use of the plaintiff’s work is arguably not within an existing or foreseeable reproduction or licensing market. Plaintiffs and defendants are in distinct industries with separate markets for their authored works (fabric arts and television (Ringgold); still photography and Hollywood (Sandoval)). And the harm to plaintiffs in both cases is not a competitive substitutionary harm; defendant’s use is not a market replacement for plaintiff’s work or a labor-saving device.