Michael P. Goodyear*

Download a PDF version of this article here.

Platform liability is a complex landscape under U.S. law. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act has generated significant scholarly and political interest due to providing platforms with broad immunity for their users’ torts. In addition, many intellectual property law scholars have examined the requirements of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (“DMCA”), which provides safe harbors for users’ copyright infringements. The DMCA enumerates a long series of requirements that online platforms must satisfy to be immunized for their users’ infringements, including a notice-and-takedown regime, a repeat infringer policy, and a prohibition on having the right and ability to control and a direct financial benefit.

There is also a third, more opaque and less scrutinized regime: trademark law’s common law notice-and-takedown system stemming from, most notably, the Second Circuit’s decision in Tiffany v. eBay. While the DMCA provides a large set of statutory requirements, the Tiffany v. eBay framework says very little beyond requiring removal of content upon specific knowledge that it is infringing a trademark. The common law is—as of yet—a general standard.

This Article seeks to understand how private ordering for online platforms’ trademark infringement notice-and-takedown policies has developed under this general common law standard. This study examines the trademark policies and other publicly reported practices of nearly four dozen major online platforms in marketing-related sectors, including social media, blogging and reviews, e-commerce, and print-on-demand. There is necessarily ambiguity about how platform private ordering has developed in the trademark context. The findings suggest that the DMCA is a significant influence on the trademark notice-and-takedown practices online platforms have adopted. Nonetheless, the capaciousness of common law notice-and-takedown has allowed platforms to vary their policies and practices considerably. Some platforms have adopted more onerous takedown requirements, while others seem to streamline procedures for rights owners. Platforms in the same sector seem to adopt each other’s practices more frequently. These findings not only help us understand how online trademark infringement policies have developed, but also provide a guide as to how private ordering may influence future common law standards in trademark and other areas of law, especially if Congress repeals Section 230 and platforms can face liability for their users’ torts.

Introduction

Intellectual property provides a unique vantage point into content moderation law and practice. In the United States, a federal law known as Section 230 provides a general liability shield for platforms for most of their users’ torts.1 Five areas of law lie outside Section 230’s protections, however, including intellectual property.2 In the absence of Section 230, separate frameworks emerged for copyright and trademark law. Congress enacted the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (“DMCA”) to provide platforms with a series of liability safe harbors for their users’ copyright infringement in exchange for complying with a multifaceted set of requirements centered on a notice-and-takedown regime.3 Many scholars have previously examined the DMCA and related secondary liability doctrine under copyright law.4

No equivalent exists for trademark law.5 Instead, courts—most notably the Second Circuit in Tiffany v. eBay—crafted a common law notice-and-takedown regime based on knowledge of specific instances of infringement instead.6 Common law notice-and-takedown for trademark infringement requires the removal of content upon knowledge that it is infringing.7 However, unlike the DMCA, trademark law provides hardly any other rules for notice-and-takedown. The literature on trademark secondary liability doctrine is limited, especially in relation to platforms.8 While the trademark literature has addressed Tiffany v. eBay, it has largely not looked beyond the case and its progeny to determine how platform practices have emerged within this general common law notice-and-takedown structure.

This Article offers the first study of platforms’ trademark infringement policies and practices to determine how the general common law standard of Tiffany v. eBay has influenced platforms’ private ordering.9 This study examines a sample of forty-five large platforms in markets in which trademark infringement is fairly likely to occur: social media, blogging and reviews, e-commerce, and print-on-demand.10 While this is a small fraction of all websites, it offers insights into how some of the most sophisticated and likely trademark infringement-sensitive of platforms craft their policies within the space afforded by Tiffany v. eBay. This study specifically addresses: whether the platforms’ policies—and other public information about their practices—suggest that platforms prohibit trademark infringement and related counterfeiting; the requirements for reporting infringement; repeat infringer prohibitions; the existence of takedown-plus policies that go beyond what the law requires; and counter-notice procedures for reported users.11 This study is limited to publicly available material, as platforms could engage in additional, private practices in response to notices of infringement. Future qualitative work could help elucidate those additional practices, although even then platforms may not reveal the full extent of their practices or how they vary in response to different notices.

The findings of this study reveal that platforms’ policies and practices can vary widely under the common law notice-and-takedown standard, suggesting that the bare requirement of specific knowledge acts as a floor on which platforms can experiment to craft their own optimal requirements and engage in private ordering. For example, the examined platforms had thirty-nine unique requests for information in takedown notices.12 Platforms widely adopted the DMCA’s six requirements for takedown notices in the trademark context, but there was significant experimentation with requirements beyond those.13 Some of those requirements suggest greater protections for users or streamlining reporting procedures for rights owners. However, others imposed onerous trademark registration requirements on rights owners, despite the viability of false advertising, false designation of origin, and state law claims without federal registration.14 Repeat infringer policies and counter-notice procedures, which are core features of the DMCA safe harbors,15 are seemingly only available (or at least publicly acknowledged) for less than half these platforms.16 While prior scholarship has highlighted Amazon’s offering superior trademark takedown tools for certain rights owners,17 there is a wider trend of several platforms, especially in the e-commerce space, offering similar takedown-plus policies.18

These findings offer insights into both trademark law and the development of notice-and-takedown regimes for other areas of the law. General standards such as that under trademark common law offer significant flexibility for platform private ordering, but that may come at the cost of certain desired requirements such as those under a detailed DMCA-like regime. General common law standards are likely to proliferate in other areas of the law if Congress repeals Section 230. There are growing calls to amend or repeal the law, with politicians on both sides of the aisle having criticized Section 230 and proposed new legislation.19 In addition, courts may exclude other causes of action such as right of publicity misappropriation under existing Section 230’s exceptions.20 At least in the short term, the common law would likely bridge any gaps in statutory law for platform liability. As platform liability for users’ actions would often be based on secondary liability, knowledge—the sine qua non of notice-and-takedown21—would be a key element. This makes trademark law, and this Article’s findings on platform private ordering in response to a similar common law standard, a valuable comparator for other emerging platform liability doctrines. While weighing the normative benefits of detailed statutory rules versus general common law standards is beyond the scope of this Article, it nonetheless presents data that can contribute to future normative scholarship on law’s relationship and enticement of content moderation practices.

This Article proceeds in four parts. Part I first discusses the two most prominent safe harbor regimes for the Internet, Section 230 and the DMCA. It then explains how trademark law was excluded from these regimes and how, instead, a common law notice-and-takedown regime has emerged from the courts, especially from the Second Circuit. Part II explains the methodology for this study on online platforms’ trademark infringement policies to determine how these policies have emerged in the absence of strict requirements like those under the DMCA. Part III presents the findings of the study on platforms’ policies and practices relating to users’ trademark infringements. Part IV offers how these findings may be valuable as common law notice-and-takedown expands to new areas of legal doctrine.

I. The Emergence and Ambiguity of Common Law Notice-and-Takedown

Online trademark law emerged in response to earlier developments in the Internet platform liability ecosystem. Users sharing and posting content across the web with ease posed new liability questions for courts and Congress. What, if any, liability should service providers and platforms bear for transmitting and hosting users’ content? In response, Congress ultimately decided to pass the Communications Decency Act, part of which, Section 230, has provided a general safe harbor for Internet services for their users’ torts.22 However, Section 230 excluded a few limited categories of claims from the safe harbor, including intellectual property law.23 Two years later, Congress passed the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (“DMCA”), which provided Internet service providers with a series of liability safe harbors for users’ copyright infringements.24 Unlike Section 230, however, the DMCA only conferred a safe harbor if the service provider complied with a series of fact-specific requirements.25

Congress never enacted a platform liability safe harbor for users’ trademark infringements. Instead, a series of court decisions, most notably the Second Circuit’s decision in Tiffany (NJ) Inc. v. eBay Inc., crafted a common law notice-and-takedown regime.26 While its common law origins provide the trademark safe harbor with some flexibility, Tiffany v. eBay and its successors have not defined all the requirements of the safe harbor. This opaqueness leaves platform liability for trademark infringement somewhat uncertain compared to the rule-based structure of the DMCA.

A. Section 230

Dubbed “the twenty-six words that created the Internet,”27 Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act provides a safe harbor for Internet services for tortious user-generated content.28 The Internet was a paradigm shift in information technology. Unlike paper publications, individuals publish and access millions of pieces of online content daily.29 It would be impossible for services to review each of them and maintain the quantity of content available online. But some of this content would undoubtedly be tortious, and it would be socially beneficial to encourage providers to restrict its dissemination.

However, early litigation on Internet service provider liability for user-generated content resulted in the opposite incentives. In Cubby, Inc. v. CompuServe Inc., the District Court for the Southern District of New York held that an electronic library service that did not review any of the content posted by users could not be held liable for that content because it did not know or have reason to know of the contents.30 While that outcome benefited CompuServe, it suggested a troubling rule for future cases: if a service provider did review its user-generated content, it could be liable for any tortious conduct contained within.31

One court made that implication explicit four years later. In Stratton Oakmont, Inc. v. Prodigy Services Co., a local New York Supreme Court held that if a service provider regulated user-generated content at all, it was liable for all uploaded content on its service that was not removed.32 Therefore, Prodigy, the operator of a computer bulletin board, was potentially liable for its user’s alleged libel against the plaintiff because it held itself out as curating the content of the bulletin board and was therefore akin to a publisher.33 The court explicitly declined to require curation of content, but it reasoned that if one chose to curate, it opened itself to liability.34

The following year, troubled by the outcome of Stratton Oakmont, Congress enacted Section 230 as part of the Communications Decency Act.35 Section 230 provides two safe harbors that countered Stratton Oakmont. First, no interactive computer service is the “publisher or speaker” of any user-generated content.36 Second, an interactive computer service is not liable for good faith efforts to restrict objectionable content (i.e., to moderate content).37 The explicit purpose behind these provisions was to promote the continued development of the Internet and other interactive computer services while encouraging increased content moderation by Internet services.38 According to the drafters, Senator Ron Wyden and former Representative Christopher Cox, Section 230 also intended to recognize the “sheer implausibility of requiring each website to monitor all of the user-created content that crossed its portal each day.”39

Shortly thereafter, Section 230 was put to the test. In Zeran v. America Online, Inc., the plaintiff accused AOL of unreasonably delaying in removing allegedly defamatory user-generated messages from its bulletin board service.40 The messages featured purported sales of t-shirts emblazoned with tasteless slogans relating to the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing.41 The post directed interested parties to contact “Ken” at plaintiff Zeran’s home phone number, leading to Zeran receiving a high volume of angry messages, including death threats.42 The Fourth Circuit held that Section 230 immunized AOL for the alleged defamation—even if it had notice that the content was defamatory—because AOL was immunized from liability for user-posted content under Section 230.43 The court parroted the reasoning of Congress in enacting Section 230, noting that “[t]he amount of information communicated via interactive computer services is…staggering. The specter of tort liability in an area of such prolific speech would have an obvious chilling effect [and]…liability upon notice [would] reinforce[] service providers’ incentives to restrict speech and abstain from self-regulation.”44

Following the seminal Section 230 decision in Zeran, courts across the United States have applied Section 230 to immunize online services from liability for user-generated content. Section 230 has provided a safe harbor for a wide variety of tort claims, including defamation,45 invasion of privacy,46 offline product injuries,47 terrorism,48 offline physical harms,49 fraud,50 negligence,51 and doxing,52 among many others. It has therefore served as a powerful shield for online platforms, leading to early dismissals of cases involving user-generated content.53

B. The Digital Millennium Copyright Act

But Section 230 is not a universal shield. The statute carves out five areas of law from the confines of its safe harbor, including intellectual property laws.54

Yet liability for copyright infringement posed similar challenges to the cabined liability and proper incentives Senator Wyden and Representative Cox wished to encourage. The same year the New York state court decided Stratton Oakmont, Judge Ronald Whyte decided the seminal online copyright infringement case Religious Technology Center v. Netcom On-Line Communication Services.55 In that case, the plaintiff copyright owners sued Netcom for direct copyright infringement because it provided Internet services to the online bulletin board on which a user—a former Scientology minister—posted several copyrighted Scientology texts.56 Prior to Netcom, the few cases to decide parallel facts held the service providers liable for the infringement.57 But Judge Whyte rejected the plaintiffs’ direct infringement theory, worrying that such a rule “could lead to the liability of countless parties whose role in the infringement is nothing more than setting up and operating a system that is necessary for the functioning of the Internet.”58 He reasoned that if Netcom were liable at all, it should be secondarily liable.59

In response to the concerns raised in Netcom and its predecessors, Congress intervened by, ultimately, passing the Online Copyright Infringement Liability Limitation Act (“OCILLA”) as part of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (“DMCA”) in 1998.60 Codified as Section 512 of the Copyright Act, the DMCA provides for four distinct safe harbors for different types of online service providers.61 These four safe harbors provide platforms with immunity for their users’ copyright infringements. Even if they cannot avail themselves of the safe harbor a rights owner would still need to affirmatively establish that the platform is liable, whether under a contributory or vicarious liability standard.

To be eligible for any of the safe harbors, a service provider must meet two threshold requirements:

- Have, inform users of, and reasonably implement a repeat infringer termination policy; and

- Accommodate and not interfere with standard technical measures.62

Each of the four safe harbors has slightly different additional requirements. The safe harbor that has garnered the most litigation is § 512(c), which is for user-generated content on platforms.63 Section 512(c) has a host of requirements for service providers in addition to the threshold repeat infringer policy and standard technical measures requirements, including:

- No actual knowledge that user-generated content is infringing;

- No red flag knowledge that user-generated content is infringing;

- Expeditiously remove infringing content once known (including in response to takedown notices);

- Not both receive a direct financial benefit from the infringing content and have the right and ability to control it; and

- Have a designated service agent to whom rights owners can submit takedown notices.64

A separate provision of the statute clarifies, however, that a service provider need not proactively monitor for infringement.65 This seems to reflect Judge Whyte’s concern in Netcom.

At the heart of the § 512(c) safe harbor is a notice and takedown system, whereby a platform is required to remove content once it learns it is infringing. Under this system, a service provider is only obligated to remove infringing content once it knows it is infringing, it gains red flag knowledge that it is infringing, or a rights owner reports that it is infringing.66 This structure is premised on the belief that, as Senator Wyden and Representative Cox noted in the Section 230 context, it is infeasible for a platform to know by itself whether content is infringing.67 However, once a rights owner informs the platform, it is reasonable to require the platform to act.68

To qualify as a legitimate takedown notice, the DMCA notes that a rights owner or their authorized representative must “substantially” include the following six items in their report to the designated service agent:

- A signature by the rights owner’s authorized representative;

- The work that was infringed, or a representative list of such works if multiple were infringed;

- The allegedly infringing material and how to locate it;

- The reporting party’s contact information;

- A good faith statement that the use of the material is not authorized; and

- A statement under penalty of perjury that the reporting party is authorized to act by the rights owner.69

If the reporting party substantially includes (2), (3), and (4), but fails to substantially include the other parts, the service provider must promptly attempt to contact the reporting party and remedy the incomplete notice.70

The DMCA also provides service providers with a liability safe harbor for removing reported material, even if it later turns out to be noninfringing, if it implements a counter notification procedure under § 512(g):

- Notify the user when the content has been removed or disabled;

- Notify the person who submitted a takedown notice if it receives a counter notification; and

- Replace removed material within 10–14 days in response to a proper counter notification if it does not learn that the reporting party has filed an action in court.71

The service provider is not liable for copyright infringement for restoring the reported material if it follows these procedures.72

These various requirements for the DMCA safe harbors are a sharp departure from Section 230, which provides a general safe harbor that is not tied to notice-and-takedown procedures, repeat infringer policies, financial benefits and control, designated service agents, or these other obligations.73 While these requirements are not paragons of clarity,74 they do put platforms on notice that they must take a variety of specific actions to avail themselves of the safe harbors. This multitude of fact-specific DMCA requirements makes obtaining a § 512(c) safe harbor much more difficult compared to Section 230. Nonetheless, like Section 230, the DMCA—and especially § 512(c)—has helped protect online platforms from rampant liability for their users’ infringements.75

C. Contributory Trademark Infringement

Unlike copyright law, which has statutory safe harbors in the form of the DMCA, trademark law instead relies on a common law notice-and-takedown mandate that gradually emerged in the courts. There was initially less concern about online trademark infringement compared to copyright infringement.76 While the Internet allows infringers to directly and perfectly copy and distribute others’ works in ways that were not possible before, the same is not necessarily true for trademarks.77 An infringer may be able to copy a trademark more easily, but trademark infringement is based not on mere copying, but on whether the use of a trademark is likely to cause consumer confusion as to the source of a good or service.78

The Lanham Act has a limited type of safe harbor for publishers of trademark infringement. Recovery against publishers—including those of electronic communications—will be limited to injunctive relief if the publisher is an innocent infringer.79 Injunctive relief will not be available where it would interfere with the publisher’s normal operation.80 But knowledge of specific infringements would nullify this innocent infringer defense.81

In recent years, a statutory standard for secondary trademark infringement liability has been proposed in the form of the SHOP SAFE Act.82 The SHOP SAFE Act has not been enacted—indeed, it has not been passed in several concurrent Congresses—but it has remained a specter.83 The SHOP SAFE Act would make online marketplaces contributorily liable for third-party listings and sales of goods that “implicates health and safety” unless they undertake certain actions, including determining that the seller designated a registered agent in the United States, verifying the identity of the seller through governmental or other reliable documentation, and imposing certain obligations on sellers.84 This is not a safe harbor like the DMCA because it would impose liability if requirements were not met rather than provide a safe harbor from liability. Dozens of trademark law professors have strongly criticized the bill for imposing stringent requirements and a new cause of action unhinged from knowledge of specific infringements.85 Regardless, the SHOP SAFE Act has not been enacted.

Voluntary best practice lists exist. For example, in 2023, the International Trademark Association (“INTA”) established a framework for protecting consumers from third-party sales of counterfeit goods via online marketplaces.86 In 2024, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (“OECD”) completed its initial Draft Voluntary Guidelines for Countering Illicit Trade in Counterfeit Goods on Online Marketplaces.87 Although these draft guidelines are not binding in their current form, they could have an effect on platforms’ practices. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) has since solicited public comments on the OECD draft and held a public roundtable.88

Regardless of these efforts, online trademark infringement has occurred and the law has not advanced much after the canonical case of Tiffany v. eBay,89 raising the question of when, and under what circumstances, the hosting platform and service providers should be held liable for users’ trademark infringements. As Judge Whyte noted in Netcom, the proper framework for determining liability of online platforms for user-generated infringements is typically secondary liability.90 Secondary liability doctrine in trademark law emerged from common law principles as early as the 1920s.91 The greatest risk of secondary liability for platforms is under a contributory liability theory. In Inwood Laboratories, Inc. v. Ives Laboratories, Inc., the Supreme Court defined contributory liability under trademark law as continuing to provide a service to one it knows is engaging in trademark infringement.92

The other theory of secondary trademark infringement is vicarious liability, but trademark law’s vicarious liability test is much more stringent than under copyright law because it requires the defendant to have a high degree of control over the infringement. Vicarious trademark liability requires “a finding that the defendant and the infringer have an apparent or actual partnership, have authority to bind one another in transactions with third parties or exercise joint ownership or control over the infringing product.”93 Merely offering an online service is unlikely to create such an actual or apparent partnership, which is why most litigation over platform trademark infringement liability has focused on contributory liability. Therefore, the focus of trademark secondary liability cases in the online context has largely been on contributory liability, specifically knowledge acquisition and actions in response.

The online contributory liability test started to develop in cases like Lockheed Martin Corp. v. Network Solutions, Inc., in which the plaintiff sued a domain name registrar for trademark infringement.94 In its decision, the Ninth Circuit expanded the Supreme Court’s definition of contributory liability from Inwood Laboratories, noting that courts should “consider the extent of control exercised by the defendant over the third party’s means of infringement” when they are analyzing a service and not a product.95 Instead of determining whether the defendant “supplies a product,” courts should look at whether the service had “[d]irect control and monitoring of the instrumentality used by the third party to infringe.”96 The court held that the defendant domain name registrar did not exercise sufficient direct control and monitoring to warrant liability because it mechanically provided domain names and was not expected to monitor the Internet for infringement.97

Following Lockheed Martin, the doctrine continued to develop. Due to its common law nature, contributory trademark liability evolved with slight differences and refinements. For example, in Perfect 10, Inc. v. Visa International Service Association, the Ninth Circuit again faced the question of whether service providers—this time, credit card companies that processed payments—could be secondarily liable for users’ trademark infringements.98 The Visa court further refined the analysis in Lockheed Martin, rejecting contributory liability because, among other things, “Perfect 10 has not alleged that Defendants have the power to remove infringing material from these websites or directly stop their distribution over the Internet.”99

Undoubtedly the most significant case for online trademark infringement was the Second Circuit’s decision in Tiffany v. eBay, in which it incorporated a notice-and-takedown system into the common law. In that case, jewelry company Tiffany sued e-commerce platform eBay for user listings of alleged knockoff Tiffany rings.100 Convinced by similar rationales to the DMCA and applying the Inwood Laboratories standard, the court held that an Internet service provider can be held contributorily liable for trademark infringement only when it knows of specific instances of infringing content on its platform and fails to remove them.101 Generalized knowledge of infringement somewhere on the platform, or the mere prospect of the platform being used for infringement, is insufficient.102 Because eBay removed specific Tiffany-related content once it learned it was infringing, eBay was not contributorily liable.103

Other courts have subsequently adopted similar rules to those articulated in Tiffany v. eBay.104 An important rule from these progeny is that online platforms need not proactively monitor their services for infringement.105 Tiffany v. eBay hinted at such a rule by explaining that general knowledge of infringement existing somewhere on a platform is not enough to trigger a duty to investigate.106 The DMCA has the same rule.107 The district court in Tiffany v. eBay and some earlier court decisions had previously rejected such “an affirmative duty to take precautions against potential counterfeiters,” although the Second Circuit did not address this on appeal.108

Unlike the rule-laden DMCA, Tiffany v. eBay offers a fairly general liability standard. Beyond the specific knowledge and removal requirement, the Second Circuit and other courts have not defined what, if any, additional requirements should apply. As detailed in the previous Section, the DMCA safe harbor requires a panoply of features and obligations, including a repeat infringer policy, not interfering with standard technical measures, not having a right and ability to control and a direct financial benefit, expeditious removal, a designated service agent, specific requirements for a proper notice, and a counter-notice procedure.109 Tiffany v. eBay does not explicitly require any of these for the platform to avoid contributory liability beyond specific knowledge of infringement.110

However, the defendant, eBay, went beyond the bare requirements of the Second Circuit’s decision and engaged in commendable behavior. For example, eBay spent up to $20 million a year on trust and safety measures, including combating infringement. Its Trust and Safety department consisted of 4,000 employees, with over 200 employees working exclusively on combating infringement.111 eBay also had a repeat infringer policy.112 It removed specific infringements within twenty-four hours’ notice and 70-80% within twelve hours’ notice.113 eBay informed the reported seller why the listing was removed.114 If an auction or sale had not ended, eBay cancelled bids; if it had, eBay retroactively cancelled the transaction and refunded the fees it had collected.115 eBay had a set procedure for receiving trademark infringement reports called a “Notice of Claimed Infringement,” or NOCI.116 Although it is not required under the DMCA either, eBay implemented a “fraud engine” to automatically search and filter listings that were likely to infringe or otherwise violate eBay policies.117

The Second Circuit did not base its decision on any of these aspects of eBay’s actions.118 eBay had gone above and beyond the notice-and-takedown requirement the Second Circuit adopted. However, scholars cautioned that Tiffany v. eBay left open the possibility of finding a service provider willfully blind if it had a less legitimate business model than eBay—even if the infringing content were removed upon notice.119 Some thought that, in trademark infringement secondary liability cases post-Tiffany v. eBay, “what matters most…is whether the court believes in the defendant’s essential legitimacy and good faith.”120 Yet subsequent court decisions do not seem to have imposed requirements commensurate with eBay’s actions in the Tiffany v. eBay litigation.121 Without a statutory safe harbor, it is possible that the trademark contributory liability standard may shift to incorporate new requirements at common law. It could even draw requirements from the contributory liability standard for copyright infringement, which is currently before the Supreme Court.122

So far, in the wake of Tiffany v. eBay, the industry standard for platforms appears to be having a notice-and-takedown procedure for trademark infringements.123 Yet Tiffany v. eBay provides little guidance on what is required beyond removal of infringing content upon learning of it. While some commentators have advocated for a legislative notice-and-takedown regime like the DMCA,124 such a statute has not emerged and Tiffany v. eBay remains the standard. This leaves an open question of what additional items, if any, platforms need to employ in order to avail themselves of trademark liability safe harbors.

While the caselaw is lacking in detail, in future cases, courts and Congress may look to private ordering to determine what is reasonable to require of platforms. Custom and industry norms often have a significant influence on practice and the development of intellectual property law. For example, informal norms by copyright and trademark owners have influenced industry practice and even the law.125

Studies about the role of private ordering are replete in the intellectual property literature. Several scholars have examined intellectual property-like norms that have emerged in intellectual property’s so-called “negative spaces,” where intellectual property protections are lacking yet creativity has proliferated.126 These studies include stand-up comedy,127 roller derby,128 drag,129 tattoos,130 fan fiction,131 recipes,132 pornography,133 and jam bands.134 Other literature has examined industries where intellectual property law may apply, yet informal norms still play an important role, such as photography and craft beer.135

The rest of this Article explores how online platforms have structured their notice-and-takedown regimes under the general standard of trademark common law rather than the DMCA’s statutory rules. This is a distinct question from many prior studies on intellectual property norms and private ordering, which examined creativity norms where intellectual property law does not exist or norms that differed from the law. This study instead asks how private ordering develops where the law only offers a general standard. This Article’s findings could, in turn, influence common law developments by showing the current state of private ordering among platforms.

II. Online Trademark Policy Study and Methodology

In order to understand how online trademark law norms have developed since Tiffany v. eBay, I undertook an empirical study of websites’ trademark infringement policies. This follows a long tradition of empirical studies investigating the edges of trademark law, including on bars to registration,136 whether we are running out of trademarks,137 how courts employ likelihood of confusion analyses,138 whether investors value trademark enforcement actions,139 the success of women and racial minorities at securing trademark registrations,140 the registration of sounds as trademarks,141 the registration of colors as trademarks,142 and the use of fraudulent U.S. trademark specimens of use by applicants from China.143

This Article seeks to add to this empirical literature on trademark law by furthering our understanding of how online platforms engage in private ordering in light of the general trademark contributory liability standard at common law. Like many previous empirical studies of trademark law, I crafted a bespoke list to examine.144 It would be practically impossible to categorize every online policy that addresses trademark infringement. Instead, I created a sample of forty-five online platforms. I drew this list from four types of online platforms that are more likely than most to have user-generated trademark infringement: social media, blogging and review websites, e-commerce, and print-on-demand. These websites involve vast quantities of user posts, photos, and listings, raising the chance of trademark infringement occurring. Furthermore, trademark owners have sued these types of platforms for their users’ infringements in the past.145 Therefore, these platforms would seem to be especially incentivized to have robust trademark infringement policies to avoid liability.

The platforms that were included in the study are listed in Table 1. This sample of platforms contains the largest companies by market capitalization and user base, as well as some smaller companies to diversify the dataset. The largest platforms are well-resourced and likely to use highly sophisticated legal counsel. Smaller companies usually have fewer and less specialized attorneys. Companies in this dataset include ones worth over one trillion dollars, like Amazon, to those valued in the double-digit millions, like Redbubble.146

Table 1: Online Platforms Reviewed

| Social Media | Blog Review | E-Commerce | Print-on-Demand |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beli | Foursquare | AliExpress147 | Gelato |

| BeReal | Medium | Amazon | Gooten |

| Bluesky | TripAdvisor | Craigslist | Printful |

| Discord | Tumblr | eBay | Printify |

| Weebly | Etsy | Redbubble | |

| Fishbowl | Wix | Rakuten | Sellfy |

| Flickr | WordPress | Shopee | Society6 |

| Yelp | Shopify | TeePublic | |

| Mastodon | Temu | Zazzle | |

| Walmart | |||

| Snapchat | |||

| Telegram | |||

| TikTok | |||

| Twitch | |||

| YouTube | |||

| X (Twitter) |

The platforms referenced their policies and practices regarding user trademark infringement in different documents. Some had specific intellectual property or even specific trademark policies. Others included this information in more general Terms of Use. Many had their policies spread across multiple documents. To best capture all the available information, this study searched the platforms’ respective websites for any references to trademarks or counterfeits, as well as using an external search engine to find any hidden information. Relevant pages and questions were often only accessible through user accounts or by partially completing takedown forms. Therefore, accounts were created where they were required and a takedown report was completed for each platform that accepted such reports through online forms, up until the point of submission. No report was submitted.

Selecting what data to include in this study naturally required some subjectivity. Some of the platforms’ policies were quite detailed, while others contained practically no information. My research assistants initially collected and coded the policies for each platform. I reviewed each entry to reduce inconsistencies. For transparency, the Appendix at the end of this Article contains a chart with the compiled data.

The data collected from these policies largely drew from five unique aspects of trademark law and parallel requirements under the DMCA. First, the study confirmed that the platform prohibited trademark infringement and determined whether counterfeits are treated differently from trademark infringement, given that the Lanham Act treats them as distinct.148 Second, to determine how much trademark policies mirror the DMCA requirements, the study looked at the platforms’ requirements for reporting infringement. Third, it determined whether each platform has a repeat infringer policy. Fourth, it identified any takedown-plus policies that give certain rights owners superior advantages over standard notice-and-takedown procedures. Finally, it examined whether platforms have a counter-notice procedure for trademark infringement reports.

Other trademark liability laws around the world could also influence platforms’ practices. Nonetheless, U.S. law has had a significant impact on the development of Internet service provider practices worldwide.149 One of the most significant regulatory regimes outside of the United States is the European Union. Yet neither the European Union’s E-Commerce Directive nor its more recent Digital Services Act provide more than the knowledge and duty standard under Tiffany v. eBay in the United States.150 EU law furthers this distinction between private ordering under general standards for trademark law and more rule-laden regimes like the DMCA.

This study primarily focuses on platforms’ practices relating to reporting trademark infringement, which can be gleaned from the platforms’ policies. Platforms’ policies and other publicly available documents shed some light on platforms’ private ordering around takedown practices, including repeat infringer policies and counter-notice procedures, under the general trademark common law contributory liability standard. Further qualitative work is needed, however, to determine the exact contours of platforms’ takedown practices. For example, platforms may not always honor facially valid infringement reports, treat reports differently, or ask for additional information before a takedown occurs. Even such qualitative work would necessarily be limited because there is no guarantee platforms would reveal all of their internal practices, especially when the law does not compel it.

Despite its limitations, this study analyzes a meaningful dataset that offers insights into how online trademark infringement policies have developed in the absence of binding law. In particular, the findings in Part III show that the DMCA strongly influences platforms’ trademark infringement policies. It also shows where practices regarding users’ trademark infringements diverge from the DMCA and how industry norms are starting to align in the absence of explicit law.

III. Illuminating Trademark Notice-and-Takedown

The limited requirements of trademark law’s common law notice-and-takedown regime under Tiffany v. eBay allow platforms flexibility to craft their own bespoke policies and practices. This study of forty-five platforms’ trademark notice-and-takedown policies illustrates where private ordering in trademark notice-and-takedown diverges from the strictures of the DMCA. It also shows where some soft law norms are emerging in certain markets. At a high level, there is significant convergence between platforms’ trademark notice-and-takedown policies. Underneath, however, there is considerable experimentation and variance on the specific requirements. In turn, this Part discusses findings relating to platforms’ prohibitions on trademark infringement and counterfeiting, reporting requirements, repeat infringer policies, takedown-plus policies, and counter-notice procedures.

A. Prohibiting Trademark Infringement and Counterfeiting

Platforms’ Terms of Use and related user policies can suggest whether platforms are aware of the possibility of trademark infringement and related counterfeiting issues that could bedevil their platforms. The DMCA does not explicitly require platforms to prohibit copyright infringement in their Terms of Use, although in practice most platforms seem to remove infringing content to comply with the DMCA.151 Nonetheless, user policies offer insights into platforms’ practices.

As shown in Table 2, the vast majority (88.89%) of the forty-five platforms included in this study explicitly prohibit trademark infringement in their Terms of Use, community guidelines, or other user policies. As a threshold matter, these prohibitions suggest that the platforms are at least aware of the possibility of users infringing trademarks on their websites or mobile applications. While trademark infringement is mentioned fewer times than copyright infringement, platforms seem to be largely aware of the problem. Only five platforms do not explicitly prohibit trademark infringement. Telegram, LinkedIn, Wix, and Shopify do not explicitly prohibit trademark infringement, including counterfeiting. Mastodon prohibits infringements of its own trademarks, but does not mention infringement of others’ trademarks.152 However, LinkedIn, Mastodon, Wix, and Shopify impliedly prohibit trademark infringement because they provide instructions for reporting trademark infringement.153

Table 2: Prohibited Trademark Infringement and Counterfeiting

| Requirement | Social Media | Blog/Review | E-Commerce | Print-on-Demand | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prohibits Trademark Infringement | 15/18 | 7/8 | 9/10 | 9/9 | 40/45 |

| Prohibits Counterfeiting | 10/18 | 1/8 | 8/10 | 6/9 | 25/45 |

A slightly separate question is the issue of counterfeiting. The Lanham Act prohibits different types of infringement, while the DMCA only targets the more uniformly defined copyright infringement.154 The Lanham Act notably distinguishes counterfeiting as a particularly egregious type of trademark infringement. Counterfeits are spurious marks that are indistinguishable from the real thing.155 Rights owners can recover treble damages compared to regular trademark infringement or statutory damages of up to $2,000,000 per counterfeit mark per type of goods or services.156

Over half (55.56%) of the platforms in this study explicitly address counterfeiting. However, platforms typically do not define counterfeiting, and they could be defining it differently than the Lanham Act does.157 Like with prohibitions on trademark infringement, explicit prohibitions of counterfeiting are contained not just in the Terms of Use, but also other user policies, including community guidelines, and policies for user safety and illegal activities. In practice, however, few platforms impose substantive requirements that distinguish trademark infringement from counterfeiting, as will be discussed below in Part III.B. on reporting requirements for proper takedown notices.

B. Reporting Requirements

Unlike the rule-laden DMCA, the common law notice-and-takedown system under Tiffany v. eBay only formally requires removal upon knowledge of an infringement.158 This section examines what platforms have required for takedown notices under the general common law standard. Platforms may treat valid notices differently after they have received them, but that qualitative research is beyond the scope of this article. Instead, this section focuses on the notice portion of notice-and-takedown because knowledge of infringement is what triggers an obligation to act to avoid being held contributorily liable. This sheds light on platforms’ private ordering, which in turn could influence common law standards for notice-and-takedown by showing what is customary in the industry.

Somewhat surprisingly, out of the forty-five platforms investigated, only thirty-eight have requirements for takedown notices.159 Seven platforms do not have any requirements for trademark infringement takedown notices: five social media apps (Beli, Bluesky, Fishbowl, Mastodon, and Telegram); one review website (Trip Advisor); and one print-on-demand service (Gooten).160 They may remove reported infringements in practice, but it would be more difficult for rights owners to report infringements because they do not, at least in the first instance, know what they must include in a report. Similar concerns about the difficulty of finding information about how to report infringing content were expressed by copyright owners in comments responding to a notice of inquiry from the U.S. Copyright Office on the effectiveness of the DMCA.161 The undisclosed notice requirements are somewhat surprising since the Second Circuit in Tiffany v. eBay seemed to favor a reporting process.162 This lack of disclosure is also not consistent with platforms’ copyright practices. Six of the seven platforms have DMCA takedown procedures.163 The lack of any posted trademark notice procedures could even suggest a lack of notice-and-takedown procedures altogether, although further qualitative research is needed to draw such a conclusion.

This rest of this section discusses the practices of those thirty-eight platforms that have takedown notice policies for trademark infringement. Despite the paucity of guidance on what a formal takedown notice should require, platforms have adopted a wide variety of requirements. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the six requirements for a takedown notice under the DMCA are generally required for trademark takedown notices too. Yet these are not the only requirements; the platforms investigated in this study utilize, in total, thirty-three additional requirements and requests for information.

Of those thirty-eight platforms, the vast majority (81.58%) request that rights owners report trademark infringements via a specific form.164 The dominance of online forms for reporting trademark infringement is likely because of the ease of completing and receiving them and the ability of platforms to require reporting parties to complete certain parts of the form. The remaining seven platforms (five of which are print-on-demand services) request the information via email and do not have an online form.

Table 3: Separate Copyright and Trademark Reporting Procedures

| Social Media | Blog/Review | E-Commerce | Print-on-Demand | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Separate Copyright and Trademark Reporting Procedures | 12/13 | 6/7 | 7/10 | 2/8 | 27/38 |

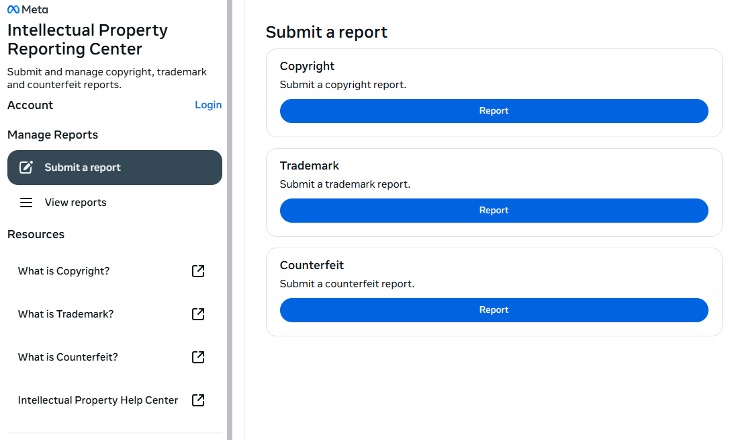

As shown in Table 3, most of the platforms (71.05%) have separate reporting forms or procedures for copyright and trademark infringements. For example, here is how Facebook’s intellectual property report page begins.165

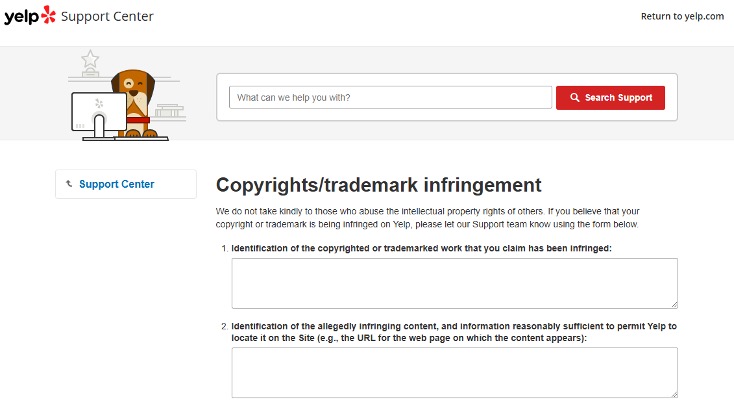

The remaining nine platforms have combined forms for copyright and other intellectual property infringements, including trademark infringement. This combined form is particularly prevalent with print-on-demand services, where only Printify and Society6 have separate trademark reporting mechanisms.166 For an example of a combined form, see this image of Yelp’s reporting form.167

Table 4: DMCA Requirements For Trademark Takedowns

| Requirement | Social Media | Blog/Review | E-Commerce | Print-on-Demand | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signature | 8/13 | 4/7 | 7/10 | 7/8 | 26/38 |

| Intellectual Property | 12/13 | 7/7 | 8/10 | 8/8 | 35/38 |

| Identify infringing material | 12/13 | 7/7 | 10/10 | 8/8 | 37/38 |

| Contact information | 13/13 | 7/7 | 10/10 | 8/8 | 38/38 |

| Good faith belief that the use is unauthorized | 10/13 | 4/7 | 8/10 | 7/8 | 29/38 |

| Penalty of perjury statement that report is true and authorized to act | 10/13 | 4/7 | 9/10 | 8/8 | 31/38 |

The most common requirements for trademark infringement takedown notices are the six requirements under the DMCA. As shown in Table 4, the most common DMCA requirements for trademark reports are providing contact information (100%), identifying the infringing material (97.37%), and stating the intellectual property at issue (92.11%). This could be a sign of doctrinal creep from the statutory DMCA into trademark common law.168 The more likely explanatory, however, is that it would be difficult for a platform to consider whether reported content is infringing without the reporting party’s information, the location of the alleged infringement, and the trademark at issue. Practically, any takedown notice would need these three things.

Most platforms have the other three DMCA requirements too, but they are noticeably less universal. Only 81.58% of platforms require a penalty of perjury statement that the report is true and the reporting party is authorized to act. Only 76.32% require a statement of good faith belief that the use is unauthorized. Finally, only 68.42% require a signature. These lower rates of adoption could suggest that some platforms view these requirements as merely procedural rather than substantive. Indeed, all three requirements could be presumed by the filing of a takedown notice in the first place. None help resolve whether there is trademark infringement. However, platforms do not necessarily eschew all three requirements. For example, WeChat has a good faith statement requirement, but eschewed a signature and penalty of perjury statement.169 LinkedIn has a signature requirement, but does not require a good faith statement and a penalty of perjury statement.170 Medium and Rakuten only require a penalty of perjury statement, not a signature or good faith statement.171 Shopee, Tumblr, and Twitch eschew all three requirements.172

The prevalence of these requirements in platforms’ policies suggests that platforms are already coalescing around perceived best (or necessary) practices. For example, the OECD Draft Guidelines encourage highly similar requirements as the DMCA for counterfeit takedown notices.173 Yet some practices, such as these, seem to already be organically emerging among platforms.

Out of these platforms, print-on-demand platforms seem particularly likely to adopt the six takedown requirements of the DMCA, even though they adopt few other requirements (as shown below). As 75% of the print-on-demand platforms had combined reporting procedures for copyright and trademark infringements (see Table 3 above), this is likely simply a matter of following the requirements of the DMCA for ease rather than any deeper reason. However, it is possible that some of this caution around experimentation and having combined practices could stem from some print-on-demand services having been held directly liable for trademark infringement, rather than secondarily liable, due to sometimes being involved in the creation of the infringing product.174 That said, courts such as the one in Tiffany v. eBay viewed additional actions beyond the bare floor of knowledge favorably,175 so these platforms likely could add additional requirements without facing an increased liability risk.

Platforms have also adopted a wide variety of additional requirements for trademark infringement reports. These thirty-three additional requirements across thirty-eight platforms largely relate to seven areas: (1) the reporting user’s account; (2) information about the rights owner; (3) trademark registration information; (4) information about the trademark; (5) information about the alleged infringement; (6) alternative dispute resolutions; and (7) administrative requirements.

Table 5: Account Requirements for Trademark Takedowns

| Requirement | Social Media | Blog/Review | E-Commerce | Print-on-Demand | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Requires an account and having uploaded intellectual property information | 0/13 | 0/7 | 3/10 | 0/8 | 3/38 |

| Must be signed in | 0/13 | 0/7 | 6/10 | 0/8 | 6/38 |

| Are you a seller on the platform? | 0/13 | 0/7 | 1/10 | 0/8 | 1/38 |

| False report could lead to account suspension or termination | 0/13 | 0/7 | 2/10 | 0/8 | 2/38 |

As Table 5 summarizes, the account requirements for reporting trademark infringement are fairly rare overall, but they are more common on e-commerce platforms. These sign-in requirements can be more burdensome for rights owners, which would have to create accounts even if they would not otherwise use the e-commerce service. Sixty percent of the e-commerce platforms in this study—Amazon, eBay,176 Etsy, Shopify, Temu, and Shopee—require reporting parties to sign in to their platforms to submit a report. Half of these (Etsy, Temu, and Shopee) also require rights owners to have uploaded information about their intellectual property in advance.177

The similarity of these requirements across e-commerce platforms may demonstrate the sociological concept of institutional isomorphism, or how businesses in an industry tend to develop similar norms and practices.178 Standard requirements can spread across platforms due to a desire for perceived legitimacy and associated coercive, mimetic, and normative pressures.179 There may be an associated perceived benefit of avoiding liability by being in lockstep with competitors’ practices. They may also spread through shared legal representation or business management. In-house counsel may move to other platforms and share their expertise, which is informed by their prior employer. Employees on the business side may also migrate their practices from employer to employer. Platforms may also have the same outside counsel, who are likely to advise them in a similar manner on notice-and-takedown practices.

Other account-related trends are less common, but still cabined to the e-commerce space. Amazon asks whether the reporting party is a seller on the platform.180 Amazon and Walmart also note that by submitting the report, the reporting party understands that if the report is false, the platform may suspend or terminate their account.181 It is surprising that more platforms do not mention consequences for submitting false reports. The DMCA provides damages for material misrepresentations in copyright infringement reports.182 While this provision of the DMCA has been roundly criticized as being ineffective,183 platforms could—like Amazon and Walmart—adopt their own false report policies that could be more effective by suspending or terminating user accounts.

Table 6: Rights Owner Requirements for Trademark Takedowns

| Requirement | Social Media | Blog/Review | E-Commerce | Print-on-Demand | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rights owner’s name and information | 8/13 | 3/7 | 6/10 | 1/8 | 18/38 |

| Rights owner’s website | 3/13 | 3/7 | 0/10 | 0/8 | 6/38 |

| Is the reporting party or rights owner in the EU? | 1/13 | 0/7 | 0/10 | 0/8 | 1/38 |

| Relationship to the rights owner | 7/13 | 5/7 | 6/10 | 2/8 | 20/38 |

| Proof of authorization by rights owner | 3/13 | 0/7 | 1/10 | 0/8 | 4/38 |

Table 6 shows that the practice of requiring the rights owner’s name and information (52.63%) and relationship to the rights owner (47.37%) in a takedown notice is prevalent across roughly half of the platforms in the study. Both requirements are most prevalent on social media (53.85% and 61.54%) and e-commerce platforms (60%), and print-on-demand services require them the least (25% and 12.5%). The prevalence on social media and e-commerce platforms (and to a lesser extent blog and review websites) may further suggest growing industry norms for requiring information on rights owners and the relationship with the reporting party. Other requirements relating to rights owners are far less common. Only six platforms require the rights owner’s website (Facebook, Pinterest, LinkedIn, Wix, Medium, and Foursquare). Only four platforms (TikTok, WeChat, LinkedIn, and Temu) require proof of authorization by the rights owner, which is an additional hurdle for the reporting party, albeit not as onerous as the sign-in requirement discussed above.184 Only Discord asks whether the reporting party or rights owner is located in the European Union, demonstrating the potential impact of laws from other jurisdictions.185

Table 7: Registration Requirements for Trademark Takedowns

| Requirement | Social Media | Blog/Review | E-Commerce | Print-on-Demand | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trademark registration required | 5/13 | 5/7 | 5/10 | 1/8 | 16/38 |

| Documentation of registration | 9/13 | 5/7 | 2/10 | 3/8 | 19/38 |

| Is your trademark registered? | 2/13 | 3/7 | 0/10 | 0/8 | 5/38 |

| Registration number (overall) | 8/13 | 6/7 | 8/10 | 1/8 | 23/38 |

| Registration number (registration not required) | 4/13 | 1/7 | 3/10 | 1/8 | 9/38 |

| Registration office/jurisdiction | 11/13 | 3/7 | 6/10 | 0/8 | 20/38 |

| Location of use | 1/13 | 0/7 | 0/10 | 0/8 | 1/38 |

The DMCA does not require that a rights owner have registered their copyright prior to reporting the alleged infringement.186 As a practical matter, however, a copyright owner in the United States can only pursue litigation once there has been a final adjudication on their registration application.187 Yet, as Table 7 shows, 42.11% of the platforms in this study require the trademark to be registered before one can file an infringement report. 50% of platforms also ask for documentation of registration, although this does not encompass all of the platforms that require trademark registration. Foursquare, eBay, Shopify, and Shopee require only the registration number and jurisdiction, not documentation to verify the registration.188 Facebook, YouTube, WeChat, Discord, Mastodon, Tumblr, and Printify ask for documentation of registration, if applicable, but do not require registration.189

The registration requirement can be an arduous condition that is a stark break from the DMCA precedent. Not only do trademark applications with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office cost more than copyright applications with the U.S. Copyright Office ($250 or $350 per class, compared to as low as $45),190 but trademark registrations require maintenance fees of $525 per class every ten years.191 While copyright applications are relatively straightforward and the barriers to registration are fairly low, the greater complexity of trademark applications may, in effect, require applicants to retain legal counsel, adding additional cost.192 On average, a trademark registration also takes longer than a copyright registration: seven-and-a-half months compared to as low as one month.193

This requirement is somewhat surprising given that, unlike copyright law, trademark owners can bring actions for false designation or origin or false advertising based on common law trademark usage without a federal (or state) registration.194 This increases the chance of a rights owner with a viable trademark-related claim being unable to avail themselves of notice-and-takedown. However, while an unregistered copyright is likely valid in most cases due to the low threshold for qualifying for a copyright,195 the validity of an unregistered putative trademark is unclear without more since a bona fide trademark comes from use in commerce and consumer recognition rather than merely being creative.196 Therefore, platforms may be reluctant to evaluate common law trademarks.

For example, Society6 explicitly notes that it is “not in a position to evaluate the validity of trademark rights asserted as a state trademark registration, as a common law (use-based) mark, or as a mark registered in another country.”197 It is unclear how a court would view this trademark registration requirement when determining whether a platform could be held secondarily liable for a user’s misuse of a trademark, although at least some courts have held that notice of infringement and continuing to provide a service is sufficient to be held contributorily liable.198

Other trademark infringement notice requirements also suggest a preference for trademark registrations. A further 13.16% of platforms ask whether the trademark at issue has been registered, although they do not require registration. 60.53% of platforms ask for a trademark registration number, although not all of these platforms require trademark registration. Facebook, YouTube, Pinterest, Flickr, Tumblr, Amazon, Etsy, Temu, and Printful do not require trademark registration, but they request the trademark registration number, if applicable.199 It is unclear from the public policies alone whether these platforms treat reports with registered trademarks differently from ones with non-registered trademarks. Meanwhile, TikTok, LinkedIn, and Society6 do not require the trademark registration number as a discrete requirement, but the required trademark registration would contain the number so it would effectively be duplicative.200 Twitch is the only platform to explicitly ask for either a registration or application number for the trademark at issue.201

A majority of platforms (52.63%) also require information relating to the jurisdiction in which the trademark is registered or used. This makes intuitive sense given that trademarks are territorial and most of these platforms are available in multiple jurisdictions, if not worldwide (or close thereto).202 Twitch asks not only for the jurisdiction in which the trademark is registered, but also where the rights owner uses the mark, presumably to capture common law usage in other jurisdictions.203

Table 8: Trademark Information Requirements for Trademark Takedowns

| Requirement | Social Media | Blog/Review | E-Commerce | Print-on-Demand | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goods/services class | 5/13 | 3/7 | 4/10 | 0/8 | 12/38 |

| Type of trademark (word, logo, both) | 2/13 | 1/7 | 0/10 | 0/8 | 3/38 |

| First date of use (if not registered) | 0/13 | 0/7 | 2/10 | 0/8 | 2/38 |

| In use prior to alleged infringement? | 0/13 | 1/7 | 0/10 | 0/8 | 2/38 |

Unlike the more commonplace registration requirements for trademark takedown notices, platforms generally do not require much additional information about the trademarks themselves. As shown in Table 8, most commonly, 31.58% of these platforms request information about the goods or services classes of the trademarks. This requirement makes sense because trademarks are registered on the basis of the specific class of goods or services for which they are used in commerce.204 This relates to the odds of trademark infringement, which is determined based on a holistic examination of several factors that could suggest a likelihood of confusion between the use and the trademark owner.205 Several of these factors touch upon the class of goods or services, including proximity of the goods and likelihood of expansion.206 Less relevant is the type of trademark, which 7.89% of these platforms request, which asks whether the trademark at issue is a wordmark, a logo, or both. Future qualitative work could help reveal how the class affects platforms’ processing of infringement reports.

Only a few platforms seem to explicitly consider common law trademark usage, compared to the many platforms that require registration. Amazon and Temu request the first date of use of the trademark if it is not registered.207 Foursquare asks whether the trademark was used prior to the alleged infringement.208

Table 9: Infringement Requirements for Trademark Takedowns

| Requirement | Social Media | Blog/Review | E-Commerce | Print-on-Demand | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description of infringing use | 13/13 | 6/7 | 8/10 | 4/8 | 31/38 |

| Type of content at issue | 7/13 | 0/7 | 4/10 | 1/8 | 12/38 |

| Was the content taken from your page? | 1/13 | 0/7 | 0/10 | 0/8 | 1/38 |

| Related to counterfeit goods | 6/13 | 0/7 | 3/10 | 0/8 | 9/38 |

| Did you conduct a test purchase? | 0/13 | 0/7 | 2/10 | 0/8 | 2/38 |

| Link to example of genuine goods | 1/13 | 0/7 | 2/10 | 0/8 | 3/38 |

As summarized in Table 9, some platforms also inquire into more specific details about the alleged infringement. The vast majority (81.58%) of surveyed platforms request that the reporting party describe the infringing use. This information can better assist the platforms in determining whether trademark infringement has occurred, especially given the multi-factor tests that trademark law uses to determine likelihood of confusion.209 About a third (31.58%) of these platforms also ask what type of content—such as username, post, image, video, or listing—is being reported. The options vary by platform because the possible types of user-generated content are platform-specific. Knowing the content at issue, such as whether the reported content is a post or an advertisement, may also help determine the type of use and whether it is a use in commerce, which is required for trademark infringement.210 TikTok also asks whether the reported content was taken from the reporting party’s page, which may suggest greater likelihood of confusion or possible copyright infringement.211

These requirements may help platforms understand whether trademark infringement has occurred. While the DMCA requires a takedown in response to a valid infringement report, Tiffany v. eBay instead seems to turn on a more abstract requirement of knowledge.212 Contributory infringement in copyright law is also premised on knowledge, but the platform could not avail itself of the DMCA safe harbor in the first instance if it does not remove content in response to a takedown notice.213 Therefore, platforms may have more room to push back on reports that do not sufficiently substantiate the alleged trademark infringement.

The remaining requirements related to infringement information seem to address concerns about counterfeits, although they are only sporadically adopted by platforms. As explained above in Part III.A., 56.52% of these platforms explicitly address counterfeits in their Terms of Use. 23.68% of platforms that have takedown policies for trademark infringement also address counterfeits in their takedown requirements, either as separate reporting forms or as questions embedded in a trademark infringement form. Facebook, YouTube, Snapchat, and X have separate reporting forms for counterfeiting.214 TikTok, Pinterest, Amazon, eBay, and Walmart ask in their trademark infringement form whether the issue is related to counterfeits.215 Amazon and Walmart also ask about whether the reporting party has conducted a test purchase, in order to ascertain whether the listed item is actually infringing or a counterfeit.216 It makes sense that e-commerce platforms would ask this question, as they are more likely to have users selling counterfeit goods than social media or blogging platforms, whose primary purposes are not selling products. Finally, Snapchat requests a link to an example of genuine goods, which is also focused on ascertaining whether the reported content is actually counterfeit.217

Table 10: Alternative Dispute Resolution Requirements for Trademark Takedowns

| Requirement | Social Media | Blog/Review | E-Commerce | Print-on-Demand | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have not been able to contact user or user refused to comply | 0/13 | 1/7 | 0/10 | 0/8 | 1/38 |

| Would modification of infringing words from name address the issue? | 0/13 | 0/7 | 0/10 | 1/8 | 1/38 |

An uncommon category for trademark takedown notice requirements is related to alternative dispute resolution. Foursquare asks whether the reporting party had previously tried to contact the allegedly infringing user or whether the user refused to comply.218 Redbubble asks whether modifying the listing description or name would address the reporting party’s trademark-related concerns.219 While these are outliers, they demonstrate that some platforms may be using the generality of the Tiffany v. eBay framework to help parties consider alternative resolutions to wholesale removal of the content.

Table 11: Administrative Requirements for Trademark Takedowns

| Requirement | Social Media | Blog/Review | E-Commerce | Print-on-Demand | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Report may be shared with third parties | 8/13 | 5/7 | 2/10 | 1/8 | 16/38 |

| Contact information for reported party | 0/13 | 0/7 | 1/10 | 0/8 | 1/38 |

| Agree to bear all legal consequences of the report | 1/13 | 0/7 | 0/10 | 0/8 | 1/38 |

| Supporting documentation | 4/13 | 2/7 | 1/10 | 0/8 | 7/38 |

| Documentation to confirm identity | 1/13 | 0/7 | 1/10 | 0/8 | 2/38 |

| Subject line | 4/13 | 0/7 | 2/10 | 0/8 | 6/38 |

Beyond these more specific categories of requirements for trademark takedown notices, some platforms request additional information that is often more administrative. 42.11% of these platforms require the reporting party to acknowledge that their report may be shared with third parties. This requirement may also show institutional isomorphism because practices are converging, likely due to coercive, mimetic, and normative pressures.220 AliExpress asks whether the reporting party has contact information for the user they are reporting, which may be unusual but could allow an additional line of contact with the user.221 TikTok asks the reporting party to agree to bear all legal consequences of the report.222 18.42% of surveyed platforms offer reporting parties the option of providing supporting documentation or attachments related to the alleged infringement. Most platforms do not publicly provide further information about what would be helpful documentation, but Snapchat specifically references images of the original work, screenshots of the infringing content, and registration certificates.223 X and AliExpress request documentation in the form of a valid government-issued photo ID to confirm the identity of the reporting party or, for AliExpress, an operation license or business registration certificate where the reporting party is a corporate or business entity.224 10.52% of these platforms also ask the reporting party to include a subject line in their report.

***

Overall, while platforms have varying practices regarding reporting trademark infringement, there are four salient trends worth noting: a reliance on the DMCA, experimentation, similar adoption among industry competitors, and heightened reporting requirements for trademark takedowns.

First, the DMCA has a dominant influence on reporting requirements. A supermajority of these platforms has adopted all six requirements for valid takedown notices under the DMCA. Platforms are especially likely to adopt the three substantive requirements from the DMCA: stating the intellectual property at issue, identifying the infringing material, and providing the reporting party’s contact information. This information would likely be needed at the bare minimum to act on any takedown notice. Expanding on the second requirement, platforms are requiring a description of the infringing use, which especially makes sense in the trademark context where a likelihood of confusion must be determined based on a holistic review of several factors.

Second, the more open standard of Tiffany v. eBay allows for some experimentation by platforms. This undoubtedly contributed to these platforms having varying selections of thirty-nine unique requirements for reporting trademark infringements. Some platforms are also imposing additional requirements for copyright infringement notices,225 although these requirements are arguably riskier from a legal standpoint due to the strictures of the DMCA, which require acceptance of any notice with substantially all six elements.226

These thirty-nine requirements cover a diverse range of topics. Although they are rare, some platforms have encouraged rights owners to conduct test purchases, try and resolve the issue directly with the allegedly infringing user, or consider alternative fixes that would not require deleting all the reported party’s content. Others have threatened to impose consequences for bad faith takedown notices, including suspension or termination of accounts. Some have also required more information about the relationship of the reporting party and the rights owner to confirm they are authorized to act.

Together, these and other requirements explored in this section suggest that platforms are using the space provided by common law notice-and-takedown to experiment with different practices to achieve their goals. Private ordering can provide an attractive alternative to blunt default rules of trademark law.227 At minimum, platforms could act as laboratories in which they can determine which norms and practices are optimal for them and for trademark and user protection.228

The breadth of different requirements suggests that trademark’s common law notice-and-takedown regime may not suffer from the perceived risk of rule-laden safe harbors converting floors into ceilings.229 Instead, Tiffany v. eBay is operating as a floor on which many platforms are experimenting to craft optimal frameworks for themselves, rights owners, and their users. This may lead platforms to a virtuous place where they seek to draw an appropriate balance between imposing obligations on trademark owners and over-enforcing their rights.

However, as commentators have warned in the copyright context, too diverse a range of takedown procedures can cause inefficiencies for rights owners.230 Indeed, a list of best DMCA notice-and-takedown practices developed by stakeholders and the U.S. Department of Commerce encouraged platforms to use industry-standard features to streamline the submission of takedown notices by rights owners.231

An additional concern is that the common law does not necessarily mandate the best practices. Optimal practices that have been adopted by some platforms are often far from universal. For example, despite sound reasons for imposing consequences for bad faith takedown notices, only two platforms explicitly mention these in the trademark context. Some platforms may instead adopt requirements that unfairly favor platforms and users over rights owners. Some of these more troubling requirements are discussed on the next page.232 Such policies could impede justice and undermine balance in trademark law. Yet the law could ultimately correct for this through Congress adopting statutory requirements, like the DMCA, or courts considering the reasonableness of these requirements in relation to industry norms. Platforms’ experimentation with requirements may help inform the industry, policymakers, and courts about which requirements are optimal and ultimately lead to their wider adoption.

Third, there seem to be some similar (albeit not universal) adoptions of requirements among close peer-competitors. This again suggests institutional isomorphism and the presence of coercive, mimetic, and normative pressures that cause convergence among industry members.233 For most of these requirements, the majority of adoptees are in the same industry. For example, all six platforms that require the reporting party to be signed into the system prior to reporting infringement are e-commerce platforms. Most of the social media and e-commerce platforms ask about the registration office or jurisdiction, while fewer blogging sites and no print-on-demand sites inquire. Mostly social media platforms ask what type of content is at issue and whether it is related to counterfeit goods.