By Celia Lerman*

A pdf version of this article may be downloaded here.

Introduction

Does copyright law protect graffiti? This is a question of growing importance in today’s art scene. Books, CD’s, t-shirts and other items featuring graffiti images are often released without permission from the original graffiti artists. For a recent example, take the graffiti exhibition mounted in a Buenos Aires art gallery by Peruvian artist José Carlos Martinat. Martinat’s exhibition consisted of appropriated pieces of graffiti that he had carefully removed, without permission, from the walls of private properties in Buenos Aires. Martinat also offered these pieces for sale. Local graffiti artists reacted furiously to this exhibition and collectively destroyed all of their graffiti pieces in situ during the gallery’s opening night. Examples like this lead us to wonder if graffiti artists could receive any protection under copyright law.[1]

At least some pieces of graffiti are suitable for copyright protection, insofar as they are original works, fixed in a tangible medium of expression. Still, why should we protect expressions created by an illegal act (painting a third party’s property without her permission)? Should the law help graffiti artists to benefit from their transgressions? Moreover, if the primary purpose of copyright is to incentivize the creation of valuable creative works, should we protect and promote illegal art?

Following an overview of recent cases concerning graffiti in Section I of this Article, Section II will argue that when graffiti complies with the minimum requirements for copyright protection (an original work, fixed in a tangible medium of expression), it should be protected under copyright law despite its illegality. As will be explained in Section III, this is because copyright should be neutral towards works created by illegal means. Because copyright should only be concerned with the immaterial work, the artist’s material transgressions should not exclude the work from copyright protection. Section III will also show that copyright protection for graffiti may be justified even under the incentive-based scheme of the U.S. Copyright Act. Illegal graffiti pieces are creative works of authorship that can fit into the concept of promoting “the Progress of Science and useful Arts,” as stated in the United States Constitution.[2] Protecting graffiti under copyright law, moreover, may incentivize graffiti artists to create more legal works.

Section IV analyzes the challenges that artists face when enforcing their rights in their graffiti under the Copyright Act and the Visual Artists Rights Act (“VARA”). I will claim that VARA can protect graffiti against modification and destruction from third parties, but not from the wall owner, whose property rights were violated when the graffiti was created. I will also argue that graffiti artists can fully claim their rights of attribution under VARA.

I. A Rising Artistic Movement Where Ownership Raises Concerns

Graffiti is one of the fastest growing artistic movements.[3] It has been compared to the cubist revolution,[4] and regarded as the twenty-first century heir to Pop Art.[5] Graffiti pieces can be found in all sorts of spaces with significant public exposure (streets, means of transport, and buildings), chosen carefully by graffiti artists to give high visibility to their work.

The term “graffiti” has both a broad and a narrow meaning. The broad meaning refers to an artistic movement that includes several different styles (spray-paint graffiti, street art and stencils), which, in turn, are associated with different socio-cultural groups. The narrow meaning only refers to spray-paint graffiti. In this article, unless otherwise noted, I will use the term “graffiti” only in the broad sense.[6] Moreover, I will primarily focus on illegal graffiti, that is, graffiti that has been fixed to a surface without permission from the surface’s owner.

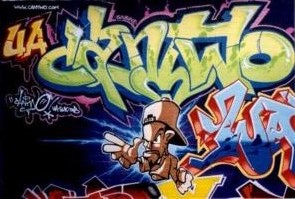

Spray-paint graffiti includes elaborate signatures and tags, along with murals and other graphic pieces created with spray paint.[7] This technique is used not only by graffiti artists, but also by gangs to mark their territory, sports fans to support their teams, and by political groups to advance their causes. Spray-paint graffiti generally has a message that is written by and for the graffiti community: few people–generally those either from the same gang culture, or people from the same artistic community–understand the meaning of such graffiti pieces.

|

|

|

|

By contrast, street art techniques go beyond just spray-cans.[9] They range from traditional painting with brushes, rollers and palettes, to more innovative forms of expression such as stickers, posters, lighting installations and mosaics.[10] Street art, moreover, is often purely artistic: by this I mean that, unlike spray-paint graffiti, street art is an aesthetic work that the general public is able to interpret and with which the public can connect.

|

|||

|

|

||

Stencil graffiti combines elements from spray-paint graffiti and from street art. Stencil artists carefully prepare stencil blueprints on hand-made sheets, which they then place on a surface and cover with spray paint. Stencil graffiti works are the easiest and quickest pieces to replicate.[12] Like spray-paint graffiti, stencil art is created with spray-paint, and like street art, stencil art is generally artistic.

|

|

|

Graffiti pieces increasingly attract the attention of numerous collectors, gallery owners, publishers, filmmakers, and journalists. Pieces from famous graffiti artists have sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars in the art market.[14] Graffiti pieces have even been given as diplomatic gifts.[15] Galleries are seeing record attendance at exhibitions of graffiti works,[16] and publishers have generated a boom of photographic books on graffiti and street art.[17] As graffiti has grown in popularity, several conflicts have highlighted issues regarding the rights graffiti artists have with respect to their work.

The first group of examples involve the unauthorized reproduction of graffiti through other means of expression, such as books, clothing, film, and TV advertisements. For example, photographer and graffiti aficionado Peter Rosenstein published the book, Tattooed Walls,[18] which displays over one hundred pictures of New York City murals. Rosenstein had accumulated these photographs over the course of a decade; he then compiled and published these images without permission from the graffiti artists whose works were featured. Soon after publication, a dozen artists who created some of the book’s murals—including the group Tats Cru—sought a settlement from Rosenstein.[19] Rosenstein explained that he did not ask for permission because “the murals were in public spaces,”[20] and because he thought the publication “was covered under fair use provisions.”[21] However, US copyright law does not support these arguments, as we shall see below.[22] Eventually, a settlement was reached and the book was quickly taken out of the publisher’s catalogue.[23]

Another example of a book that reproduced graffiti without permission is Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2 Official Strategy Guide, published by Pearson Education a/k/a Brady Publishing. The book features a mural by Chicago’s graffiti artist Hiram Villa, known as “UNONE,” without the artist’s consent. Villa brought copyright infringement and state law claims against the publishers, but the court initially dismissed his case for lack of copyright registration.[24] In its decision, however, the court explained that it “assumed, without deciding, that the work is copyrightable.”[25] Villa then registered his work with the Copyright Office and filed suit again. This time, the publisher moved to dismiss the complaint, and the court rejected the publisher’s motion.[26] Unfortunately for this paper’s analysis, the parties reached an agreement before the court could issue any substantive decision on the case, leaving the question unsettled.[27]

Graffiti has also been reproduced on clothing. For example, Urban Outfitters recently printed t-shirts that featured a signature piece by street artist Cali Killa without his permission. Cali Killa and Urban Outfitters settled the dispute, and the clothing company stopped using the artwork.[28]

|

Another example of graffiti appropriation is the swimsuit worn by the Spanish synchronized swimming team in the 2008 Beijing Olympics. The swimsuit in question reproduced German artist Cantwo’s graffiti artwork without his permission.[30] Complicating the conflict, Spanish nationals performed the infringement of the German work in China.[31] The artist complained publicly, but it is unclear whether he took any legal action against the team.[32]

|

|||

|

|

||

Films and TV advertisements have also featured unauthorized uses of graffiti. In 2011, a mural painted by the group of artists known as Tats Cru was featured without permission in a Fiat 500 commercial with Jennifer Lopez. The commercial, My World by J.Lo, emphasized the connection between the Lopez and the Bronx, and included the graffiti murals, among other distinctive scenes from her neighborhood. The parties reached an agreement regarding the commercial’s use of the mural.[34]

|

|||

|

|

||

Along with the unauthorized reproduction of graffiti pieces, there is a second group of conflicts; this group involves disputes over the preservation and ownership of physical graffiti works. One example concerns the 5 Pointz building in Long Island City, New York. The 5 Pointz building is an old, unused warehouse that has been curated by graffiti artist Meres One since 2002.[35] It serves as a center for graffiti artists in New York and is considered a landmark building both by the artists and by many locals.[36] The owner of the building, real estate developer Jerry Wolkoff, initially welcomed artists to the building[37] and currently tolerates the graffiti activity. Wolkoff has since announced, however, his intention to demolish the building in 2013.[38] Graffiti artists and supporters have started an online petition to protest the demolition of the building; the petition has received over 13,000 signatures.[39] It is unclear whether the graffiti works at 5 Pointz are legal. In order to avoid criminal liability for their graffiti, the artists would need to show that they received express consent to paint on the site.[40] However, as this piece will argue, any questions of civil liability remain intrinsically tied to determinations of copyright.[41]

Peruvian artist José Carlos Martinat’s exhibition in Buenos Aires illustrates this category of conflicts as well. Martinat mounted an exhibition that consisted of appropriated pieces of graffiti that he had carefully removed without permission, using a special art-removal technique, from the walls of private properties in Buenos Aires.[42] He only removed art that was not signed (but whose authors could be found within the local street art scene, given their characteristic style and strong presence in the local graffiti community) and small sections of larger murals that were signed.

|

|

|

|

In an act of “vandalism against vandalism,”[44] Martinat offered these removed pieces for sale in an art gallery. Local graffiti artists reacted furiously and collectively destroyed all of their own exhibited graffiti pieces during the gallery’s opening night.[45] Although some graffiti artists liked the conceptual foundations of the exhibition, most were enraged that an outsider had destroyed their artwork, harming not only the artists, but also the owners of the surfaces that had contained the art, as well as the local public who had previously enjoyed the art.[46]

For these artists, the story would have been different if other graffiti artists painting over their work on the same walls; this is understood as part of the natural life cycle of graffiti and as part of the artistic dialogue that street art entails. In this case, however, Martinat purposely intended to remove and modify the art for his own benefit–hijacking and ending the dialogue.[47] Martinat responded to the artists’ raid by claiming their intervention was part of his conceptual work: the vandalized vandals were vandalizing back.[48] Due to this incident, subsequent exhibitions in Brazil were cancelled.[49]

|

|

Despite its increasing popularity, graffiti is punished severely by many local authorities. Artists may not only suffer fines for damaging property, but they may also be subject to criminal sanctions in many jurisdictions.[50] State and local laws usually punish graffiti production and associated conduct, such as the possession of graffiti instruments[51] and the sale and distribution of broad-tipped markers and spray paint to minors.[52]

With these examples of conflicts and sanctions in mind, let us now analyze some central questions regarding the ownership of unauthorized graffiti art.

II. Graffiti as a Visual Work Under Copyright Law

In order to receive protection under copyright, an artistic expression must comply with the following minimum legal requirements: it must be a work of authorship that is original and fixed in any tangible medium of expression.[53] That is, the creative work must have originated with the author,[54] and its embodiment, by or under the authority of the author, must be sufficiently permanent or stable for it to be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated for a period of more than transitory duration.[55] These are the necessary and sufficient requirements for protection of artistic expression under copyright. Thus, like any other artistic piece, if a graffiti work complies with these minimum requirements, it can be protected under copyright.

Consider, for example, Keith Haring’s famous street art in the New York City subway. These works featured dancing people drawn in Haring’s characteristic style, white chalk on unused black advertising panels in the subway.[56] These drawings were distinct, original, and were fixed on subway panels, which are a form of tangible media. Accordingly, Keith Haring’s art could have been protected under copyright law.

|

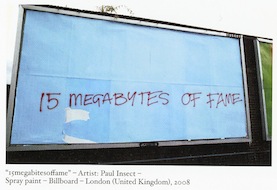

Not all graffiti, however, qualifies for copyright protection. For instance, simple tags, signatures and other spray-paint graffiti may be too small or too simple to be considered artistic “work.” Graffiti that consists of words and short phrases, familiar symbols and designs, or mere variations of typographic ornamentation, lettering or coloring cannot be protected.[58] Nor are graffiti typefaces copyrightable as such, artistic though they might be, because typefaces are not considered protectable works.[59]

|

|

Copyright’s originality requirement could also prevent some works from being copyrightable. For example, take a common phrase, such as “Lucille, I love you,” “Laura was here,” or “Vote for Obama,” painted on a wall with one or two spray paint colors in simple handwriting. Even though this visual expression might constitute a “work of authorship,” it would lack sufficient originality to qualify for copyright protection.

Usually, graffiti works are fixed in a tangible medium of expression by being painted on a wall. Since copyright law’s fixation requirement only demands that the work is sufficiently permanent or stable to permit it to be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated for a period of more than a transitory duration,[61] we should be able to identify a protectable graffiti work even if its physical embodiment is later destroyed. Copyright law distinguishes between the work and the physical support that embodies it; it only protects the former, not the latter. Most graffiti works are ephemeral because they will be painted over (either by the owner of the wall, the local authorities or other graffiti artists), or they will fade out from weather and lack of maintenance. Nevertheless, this temporary existence should be sufficient to meet copyright’s fixation requirement.[62]

Thus, if graffiti artwork is an original work of authorship fixed in a tangible medium of expression, it should be eligible for copyright protection.

Moreover, a graffiti piece could be categorized as a work of visual art.[63] This categorization is relevant only for the rights extended to the artist under the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA), which I will analyze below in Section IV. Such a designation, however, has no bearing on the copyrightability of a work under U.S. copyright law.

A piece is considered a work of visual art under VARA if: it is a painting, drawing, or sculpture; it exists in a single copy or in a limited edition of 200 copies or less; and it is signed and consecutively numbered by the author.[64] The piece is excluded from this category, however, if (i) the author did not sign it and there were no other identifying marks of his in the work;[65] (ii) it was reproduced over two hundred times;[66] or (iii) if copyright requirements were not met in the visual aspect of the work.[67] Consider, for example, an original poem painted over a wall in a bar’s bathroom with plain ink. The poet could claim copyright protection over the written text of the poem, but it will be more difficult to claim copyright over the visual manifestation (the conjunction of a text on a wall), unless it is clear that the piece is an original visual artwork.

Under the general rules of copyright ownership, notwithstanding other legal concerns about the work’s production, the author of a graffiti work should hold the copyright over it.[68] The wall owner has no claim to the copyright because he did not make any authorial contribution to the graffiti artwork. Owning the physical embodiment of a work does not confer title to the copyright.[69] The tangible and intangible aspects of a work are independent from the physical embodiment, and so are the rights over each aspect. As I will discuss in more detail below, this independence explains why a graffiti artist can validly claim copyright over a piece, even if he did not have permission to affix work to another’s property.

III. How Can We Protect Illegal Expression Like Graffiti Under Copyright?

A. Identifying Illegal Graffiti

For the analysis that follows, I will first identify instances where graffiti is illegal.

Graffiti is illegal when it is created without permission from the owner of the surface upon which the graffiti is placed.[70] The graffiti can be illegal even when the graffiti does not harm the property owner; a graffiti painting may actually increase the value of the painted property, for instance, when it is placed on a run-down building, or when a famous graffiti artist creates it.[71] Even in those cases, however, the graffiti would still be considered illegal. Although creating graffiti could provide artists with the opportunity to receive monetary rewards for adding value to another’s property,[72] this potential does not justify the illegal act.

If the owner consents to the artwork, no civil sanctions should occur because the act is covered under the owner’s property right (no matter how ugly or anti-aesthetic the graffiti is).[73] Property owners could even consent ex post facto to graffiti that was originally unauthorized. But whether such ex post consent would prevent criminal sanctions depends on the jurisdiction and on prosecutorial discretion.

Consent plays an important role in determining the legal status of a graffiti work. For example, Banksy, Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat have all created graffiti pieces with the consent of the owners of the physical property on which they are embodied. The government of Bristol, United Kingdom decided to keep one of Banksy’s controversial graffiti pieces after an open poll showed that city residents favored preservation of the work.[74] The New York City government accepted the preservation of one of Haring’s murals, entitled “Crack is Wack,” and even renamed a playground after it.[75] Owners of works by Banksy and Jean-Michel Basquiat have offered their originals for sale at considerable prices, revealing the high value they saw in the works.[76] In these cases, property owners have embraced and accepted graffiti works that were embodied on their property, and the artists were never accused of any crimes. This ex post acceptance could provide a reason not to prosecute.[77] This is especially true where a government consents to a graffiti work, as it would be surprising if the same government both criminally prosecuted and rewarded a graffiti artist for his mural.

Consent may even ratify the graffiti at 5 Pointz if the artists can show that the owner gave his implied consent.[78] Although the owner’s consent may not serve fully to deflect criminal charges under New York vandalism law, it might still help the artists fight any civil claims from the property owner.

Some have argued that graffiti should not be illegal because it is protected under the constitutional right to freedom of speech. This is the view of many graffiti supporters, who maintain that a “real solution lies in a candid application of the First Amendment,” and that “graffiti falls under the realm of symbolic speech and therefore, should be afforded First Amendment protection and be subject to the rights and limitations of freedom-of-speech precedents.”[79]

Internationally, political or meaningful graffiti could fall under freedom of speech protection when placed on public property.[80] In the Unites States, however, freedom of speech could protect graffiti in only a limited fashion, since regulations that are content-neutral, and which restrict time, place, and manner of expression, could validly restrict graffiti on public property. Content-neutral regulations are valid under first-amendment doctrine even when the public property in question could qualify as a public forum, such as a street or a park.

In Members of City Council v. Taxpayers for Vincent,[81] the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that an ordinance prohibiting the posting of signs on public property did not violate the plaintiff’s freedom of speech, relying on precedent that established the the city’s “interest in avoiding visual clutter . . . was sufficiently substantial to provide an acceptable justification for a content-neutral prohibition against the posting of signs on public property.”[82] Content-neutral regulations that are aimed at a wide range of behaviour and only have an “incidental” effect on speech are permitted.[83] Under freedom of speech jurisprudence, a content-neutral restriction of time, place, and manner is accepted if it is “narrowly tailored to serve a significant governmental interest”[84] and “leaves open ample alternative channels for communication.”[85]

For example, in Serra v. United States General Services Administration,[86] artist Richard Serra filed suit to prevent the removal of his Tilted Arc sculpture from public property, on the grounds that removal would violate his free expression rights.[87] Serra is not a graffiti artist, but this case is still illustrative due to its freedom-of-speech analysis. The United States government originally sanctioned and contracted the installation of Tilted Arc, although it later decided to remove the piece and change its location.[88] Serra maintained that Tilted Arc was site-specific, “designed for the Federal Plaza and artistically inseparable from its location,” and that removing the piece to another site would “destroy it,” depriving the work of meaning.[89] The court denied Serra’s complaint, stating that the removal of the sculpture was a permissible time, place and manner restriction.[90] This restriction conformed with the first-amendment requirements of “being narrowly tailored to serve a significant governmental interest”—namely, keeping the plaza clear of obstruction—and of there being “open ample alternative channels for communication of the information”–because there were other available means for Serra to express his artistic and political views that “did not entail obstructing the plaza”.[91]

Similar arguments could be made regarding why graffiti may be regulated under the First Amendment. Where graffiti is restricted on a content-neutral basis, it may be difficult to overturn the restriction using freedom of speech jurisprudence.

B. Illegality Is Not a Basis for Denying Copyright Protection

Now that we have identified when a graffiti work is copyrightable and when it is illegal, I will discuss why we should protect graffiti under copyright. Protecting graffiti under copyright feels wrong, intuitively. How could we let graffiti artists benefit from their crimes? Can we reward them with copyright on the one hand, while punishing them criminally on the other?

As a general legal principle, no one should benefit from his crimes. This principle is reflected in the Latin maxim ex turpi causa non oritur actio (“from a dishonorable cause, an action does not arise”). Courts have developed this principle as the doctrine of unclean hands: one cannot seek protection under the law if he has acted wrongly with respect to the matter of the complaint.[92] Does this mean that we cannot protect graffiti under copyright?

I do not believe so. We should still grant protection to illegal graffiti because the wrongdoing (fixing the work on another’s property without permission) is not relevant to the copyrightability of the work itself. Copyright should be neutral towards works created by illegal means. Indeed, copyright law imposes no negative consequences for illegal acts. Civil sanctions and criminal penalties are sufficient punishment for bad actors; copyright exclusion would be an unnecessary addition.[93]

Copyright is essentially a right in an intangible work, which is protected independent from its physical embodiment. Under copyright law, it is irrelevant if there are illegal elements in the tangible embodiment of a work (i.e., applying paint to a wall without the owner’s permission) or if the tangible embodiment of a work belongs to someone other than the author of the work. The rights (and wrongs) related to the work and to its tangible embodiment are independent, and one should not affect the other. Under the Copyright Act, “[o]wnership of a copyright, or of any of the exclusive rights under a copyright, is distinct from ownership of any material object in which the work is embodied. . . .”[94]

As long as there is a physical means by which the work is fixed, copyright should not take into account precisely which physical means is used to create or fix the work when deciding whether to grant or deny protection. To illustrate this point, there are several examples outside of graffiti where copyright protects right-infringing works.[95] Copyright still attaches to photographs taken that violate privacy rights: a paparazzi photographer has obtained copyright protection over a picture that he took of a celebrity while violating her rights to privacy,[96] and a camp counsellor obtained copyright over a picture of a minor, taken without her parent’s permission.[97] A journalist has received copyright protection over an article that reveals state secrets.[98] A student may also obtain copyright protection for a painting of a minor killing a policeman, even though the work could constitute an illegal threat under criminal law.[99]

Copyright protection is denied to a work only if the work itself violates copyright. If artist A’s work reproduces artist B’s old work without permission, then A’s work will not receive protection under copyright law. As the law establishes, “[P]rotection for a work employing preexisting material in which copyright subsists does not extend to any part of the work in which such material has been used unlawfully.”[100] Copyright law does not extend protection to works (or portions of works) that are created in violation of the exclusive rights of the same type that copyright law protects.

If U.S. copyright law included a general “illegality clause,” then copyright would not protect works that offend any other body of law. Such clauses are contained in other copyright and trademark laws around the world.[101] U.S. copyright law does not include such a provision.[102] Presumably, general illegality clauses would not be accepted in an intellectual property system like that of the United States, where copyright’s purpose is to promote, not to discourage, expression.

The unclean hands doctrine cannot be used to deny copyright protection to a work, unless the wrongful act alleged relates to the copyrightability of the work. The Fifth Circuit case Mitchell Brothers Film Group v. Cinema Adult Theater is illustrative of this point.[103]

Mitchell Bros. Film Group (“Mitchell”) owned the copyright over an adult motion picture that was exhibited, without permission, on the premises of the Cinema Adult Theater (“Cinema”). When Mitchell sued for copyright infringement, Cinema alleged that the work was not copyrightable because its content was obscene. Cinema further responded that Mitchell could not sue, based on the unclean hands doctrine. Cinema’s argument was that if Mitchell’s motion picture was obscene and therefore illegal, then Mitchell would lack the “clean hands” necessary to claim legal protection under copyright law.

The court, however, rejected Cinema’s argument and maintained Mitchell’s copyright. It explained “that there is not even a hint in the language of [the copyright act] that the obscene nature of a work renders it any less a copyrightable ‘writing’,” and interpreted this as a conscious decision by the legislature, designed to protect the broadest range of expressions.[104]

The court also ruled that the doctrine of unclean hands was not applicable, because it requires that the plaintiff’s unethical behavior be related to the subject matter of the lawsuit. In other words, Mitchell’s obscene behavior was not related to the subject matter of its claim for copyright infringement.

Specifically, the court stated: “The alleged wrongdoing of the plaintiff does not bar relief unless the defendant can show that he has been personally injured by the plaintiff’s conduct”[105] or that “the public injury . . . frustrate[s] the particular purposes of the copyright (or trademark or patent) statute.”[106] This suggests that the unclean hands doctrine might stand in a case like this, in the form of the copyright misuse doctrine.[107] The work would still be copyrightable, but the rights arising from copyright may not be enforceable against someone personally affected by the plaintiff’s conduct (such as, in graffiti, the owner of the wall), or where the particular purposes of copyright (“the promotion of originality”)[108] are frustrated in enforcing the rights over the work.[109]

Mitchell illustrates the reason it is consistent to reward graffiti artists with copyright on the one hand, while punishing them with criminal sanctions on the other: just as Mitchell was subject to obscenity laws, graffiti artists are subject to vandalism laws. However, their work can still be protected under copyright, because vandalism does not preclude copyright protection.[110] As one commentator stated, “The defendant’s unethical behaviour would be vandalism, an act for which the artist may be criminally prosecuted” but that “is not the subject matter of a [copyright] infringement case.”[111] The clean hands analysis in Mitchell differs from the analysis in a typical graffiti case, however, in that Mitchell’s illegality resided in the content of the work, while the illegality in graffiti usually resides in the fixation of the work.[112] This difference, nevertheless, should not affect the analogy; in graffiti, the method of fixation itself could be considered part of the subject matter of the work. The work’s fixation provides context that could be regarded as part of the message of the work and its content. In both cases, moreover, the bad behavior of the author does not frustrate copyright’s purpose of promoting originality through exclusive rights.[113]

C. Illegal Art Can Be Protected in an Incentive-Based Copyright System

To complete the analysis, I still need to answer a fundamental question: how can we protect illegal art in an incentive-based copyright system? In such a system, the goal of copyright is to promote the creation of works that advance knowledge, or, as expressed in the United States Constitution, to “promote the progress of Science and the Useful Arts.”[114] Copyright historically protects works such as books, maps and charts, which are valuable for society. However, graffiti is made through illegal means and does not seem like the kind of work that was originally contemplated when the copyright system was established. If we protect graffiti, are we supporting and promoting the wrong type of creations? Would we be promoting the commission of illegal acts?

In the face of the arguments supra, it has been claimed that a natural-rights based theory of copyright would be more suitable for protecting graffiti than an incentive-based one.[115]

However, there are reasons that illegal art such as graffiti should still be protected under an incentive-based copyright system. Protecting graffiti is not the promotion of illegal acts, but merely the promotion of creative expressions, without looking into the legality of those expressions. Copyright does not incentivize artists to engage in illegal creative acts because copyright is neutral towards the legality of creative acts, as long as copyright laws are not violated. Granting copyright protection to graffiti will simply promote more art, regardless of whether that art is legal or illegal.

Other bodies of law, such as criminal law, are charged with addressing the bad consequences of certain creative acts, but not copyright.[116] The copyright system may limit the undesirable or illegal consequences of enforcing a copyright by means of the copyright misuse doctrine; but this doctrine only stands to limit the enforceability of a copyright, not to determine the copyrightability of a work.[117]

This is how illegal graffiti works can promote the progress of science and useful arts. Because copyrightable works do not need to be useful, as patentable inventions do, the Constitution does not restrict copyright protection to legal works only.[118]

Furthermore, in an incentive-based copyright system it is not necessary that every work promote the progress of science, but instead, that the system as a whole promotes that desired end. The system does so by granting protection to all works, regardless of their legality. So concluded the court in Mitchell, maintaining that that the Copyright Clause of the U.S. Constitution was “best served by allowing all creative works (in a copyrightable format) to be accorded copyright protection regardless of subject matter or content.”[119] The court reasoned that:

“[B]y passing general laws to protect all works, Congress better fulfills its designated ends than it would by denying protection to all books the contents of which were open to real or imagined objection. . . . Judging by this standard, it is obvious that although Congress could require that each copyrighted work be shown to promote the useful arts (as it has with patents), it need not do so.”[120]

The Supreme Court has expressed a similar view in recent cases, stating that the Copyright Clause “empowers Congress to determine the intellectual property regimes that, overall, in that body’s judgment, will serve the ends of the Clause,” but not necessarily a system in which every element needs to serve the Clause’s goal.[121]

Furthermore, as a practical matter, it is somewhat counterintuitive to believe that protecting graffiti under copyright would cause more artists to paint illegally on walls. On the contrary, granting protection may result in their looking for more legal places to paint. Copyright protection could help artists build their reputations faster and switch to painting legally on walls more quickly. Legal acceptance of the art form would also encourage graffiti artists, otherwise excluded by society, to accept the possibility of creating their art by legal means and help them to view the law as an ally rather than an obstacle. Many professional graffiti artists start painting on walls legally as their careers grow and their work becomes more prestigious, probably because it is very hard to develop an artistic career through illegal graffiti only.[122] Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Brazilian artists Os Gemeos, and many others switched to legal art when they gained renown, and realized the commercial potential of their work.[123]

Of course, this does not mean that all graffiti artists would switch to legally painting if graffiti were copyrightable, since many artists choose to paint illegally in order to convey a rebellious message. However, copyright would give graffiti artists greater incentive to paint legally. Copyright is especially valuable for artists with growing reputations, as copyright protection could help them advance their careers.

Although obtaining copyright protection for graffiti artists’ work would benefit all graffiti artists, it would benefit some more than others. It seems that copyright would be less valuable, for example, to spray-paint graffiti artists who write messages intended solely for the graffiti community, or to artists who reject property rights in general and do not want to keep control over reproductions of their works.[124] Conversely, copyright would be more valuable to artists who develop art for the broader community or who seek to commercialize their work.[125] Even though some graffiti artists would be unmoved by copyright’s incentives, we should still grant copyright protection to graffiti. Under the United States copyright regime, authors receive copyright protection for their qualifying works, regardless what motivated the author to create; it is not necessary that every work serves the Copyright Clause’s goal, but rather that the overall system does.[126]

IV. Challenges to the Enforcement of Artists’ Rights in Their Graffiti

As the examples and cases from Section I show, two important issues for graffiti artists are control over reproductions and preservation of works. We should keep in mind, however, that artists’ rights over their graffiti are limited. Indeed, an artist’s copyright extends only to the intangible aspect of the work, while rights over its physical embodiment remain with the property owner.[127]

As a consequence, the owner of a wall containing graffiti could sell the original art piece as part of the structure that contains it, or as a separate item.[128] For example, the owners of a wall that had a Banksy piece affixed to it were able to sell their wall for $200,000.[129] The owner of the wall may also destroy the painting or paint it over completely. The new owner of a building that contained one of Banksy’s works recently did so in the UK,[130] and the same could have been done in the United States.[131] Wall owners can also defend their property against third parties who try to destroy, paint over, or remove original works that have been fixed without permission, as happened recently with two Banksy murals, removed from a factory in Detroit and from a hotel in London.[132]

|

|

||

|

|||

However, there are limits to the rights that graffiti artists can assert in their work. Because graffiti artists do not own the material embodiments of their work, and since artists violate property owner rights by painting their possessions without authorization, artists cannot claim any rights over the tangible embodiments of their unauthorized works. While artists have rights over the intangible aspect of their graffiti, including the right to prevent unauthorized reproductions, they have do not have equivalent rights regarding the tangible embodiment of their work, such as the right to preserve it in its original condition, against the wishes of the owner. But they may still have certain rights to protect the tangible embodiment from actions of third parties.

A. Challenges in Enforcing Copyright

Graffiti artists should hold the copyright over their work.[134] Holding a copyright means that an artist can prevent third parties from reproducing their work in copies[135] (for example, by taking pictures); preparing derivative works based upon the copyrighted work[136] (by including images of the graffiti in other media, such as videos or posters); and distributing copies of the copyrighted work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease, or lending[137] (by commercializing or distributing images or other products which feature the graffiti). CaliKilla, Tats Cru and Villa enforced these rights in court when others reproduced their graffiti without permission and sold clothing, videos and books that infringed their copyrights.[138]

The right to display the graffiti work publicly is a special case.[139] Despite being one of the rights granted by Copyright Law, the right to display could be considered a right in the tangible embodiment of a work, which should reasonably remain with the owner of the physical property in which the work is embodied.[140] This right to display also has a unique meaning in the context of graffiti because graffiti works are displayed publicly from their creation and being displayed publicly is part of their meaning.[141] Despite this fact, artists should not have the right to display their graffiti (or for that matter, not to display, after the graffiti is created) because they have no control over the tangible embodiment of their work, which belongs to someone else. Moreover, it should be noted that copyright actions may not prevail against a wall owner, who could allege a copyright misuse defense, showing that he has been personally injured by the plaintiff’s conduct.[142]

The fact that a work is displayed in a public setting does not prevent an artist from enforcing these rights.[143] This is not true, however, in jurisdictions that provide exceptions for photographing or filming works displayed permanently to the public. This exception, with variations, exists in the United Kingdom,[144] Germany,[145] and New Zealand,[146] among other territories,[147] but not in the United States.[148]

It has been pointed out that copyright protection for graffiti works could be problematic in practice because of the difficulty of establishing the authorship of unsigned works. Unsigned graffiti works may even qualify as “orphan works,” and reproducing them may entail significant infringement risk, at least until local laws address the issue of orphan works with proper legislation.[149]

However, concerns over unsigned works are exaggerated. It is often easy to find a work’s author by asking the local graffiti community.[150] A work’s style, traces and colors usually make it relatively easy to find the artist; this is especially true today, with online communities of local artists and digital image search tools.[151] Moreover, many works are identifiable by their style even when they are not signed, and multiple artists are reachable through their websites where they publish pictures of their works.[152]

B. Challenges Under the Visual Artists Rights Act

The Visual Artist Rights Act (“VARA”) is also relevant for our analysis.[153] VARA, a piece of legislation inspired by continental moral rights and preservation laws,[154] grants authors of works of visual art the following rights:

– Right of Authorship: Authors have a “right (1)(A) to claim authorship over their works; (1)(B) to prevent the use of his or her name as the author of any work of visual art which he or she did not create; and (2) to prevent the use of his or her name as the author of the work of visual art in the event of a distortion, mutilation or other modification of the work which would be prejudicial to his or her honor or reputation;”[155]

– Right of Integrity: Authors are entitled to prevent any intentional distortion, mutilation or other modification of that work which would be prejudicial to his or her honor or reputation. This excludes, however, modifications that are a result of the passage of time or the inherent nature of the materials.[156]

– Right Against Destruction: Authors have a right to prevent any intentional or grossly negligent destruction of a work of recognized stature.[157]

The rights of integrity and against destruction do not protect the work from modifications that are a result of conservation, unless they are caused by gross negligence, or that result from the public presentation of the work, including lighting and placement.[158] VARA rights are preservationist in nature, since they only apply to the original works of art and not to reproductions.[159]

Interestingly, there is only one court decision on the protection of illegal art under VARA to date. In English v. BFC & R. East 11th Street LLC,[160] the district court ruled that illegal murals could not be protected under VARA.[161] In this case, a group of six artists filed suit to prevent the removal of an art display in a community garden, consisting of several sculptures and murals, much of which had been set up without permission on New York City property.[162]

The artists based their claims on their rights to integrity and against destruction under VARA.[163] The copyrightability of the work (the art display as a whole) was not discussed in the case.

The district court dismissed the complaint on the grounds that VARA “does not apply to artwork that is illegally placed on the property of others, without their consent, when such artwork cannot be removed from the site in question.”[164] The court considered the special circumstances in which the case arose,[165] and reasoned that the illegality of the work, “[Was] a compelling argument [for preventing VARA protection], for otherwise parties could effectively freeze development of vacant lots by placing artwork there without permission. Such a construction of the statute would be constitutionally troubling, would defy rationality and cannot be what Congress intended in passing VARA.”[166] The court also rejected the plaintiffs’ arguments, based on the doctrine of estoppel, that the passage of time meant that the government accepted the works. According to the court, such a doctrine could not apply against the government’s inactivity.[167]

The district judge did not expand on her reasoning about the potential problems with applying VARA to unauthorized art, but we may find arguments to support this finding in our analysis from Section III. The case’s finding is consistent with the application of the unclean hands doctrine. Under this doctrine, the artists could not invoke any rights over the tangible aspect of their work, including VARA rights that preserve the physical embodiment of the work, because the artists violated the city’s property rights over the same tangible object. In this case, the artists’ wrongdoings were relevant to preventing the application of VARA rights. The artists could not have gained rights over the tangible aspect of their works because the works were affixed onto another’s property without permission. Moreover, it would be unworkable to allow the author of an unauthorized work to claim the right to protect it, as this would prevent property owners from modifying their own possessions.

In line with English, therefore, the owner of a wall can remove or destroy artwork affixed to that wall without being subject to the prior notification requirement of § 113(d)(2).[168] This is an interesting inference, considering that an important part of graffiti’s artistic meaning is its location on a public site.[169] Removing a graffiti piece from its site may be contrary to the creator’s artistic intent for the work,[170] but this artistic intent is not protected by VARA: (i) VARA cannot be invoked by an artist to protect the tangible aspect of a work, including its physical location, against modification by the owner of the property in which the work is embodied or situated, and (ii) in any event, VARA does not protect the public presentation and placement of a work.[171]

Nevertheless, English should not be understood as excluding graffiti artists from having any claims under copyright law or under VARA. Under the reading proposed in this article, it is only the unclean hands doctrine and the property owner’s rights that prevent graffiti artists from asserting rights under copyright or VARA. Therefore, English should not be read as preventing simple copyright claims over unauthorized works.[172] The court’s ruling on VARA’s scope does not affect copyright protection against unauthorized reproductions of works. As the Copyright Act expressly provides, “ownership of [VARA] rights with respect to a work of visual art is distinct from ownership of any copy of that work, or of a copyright or any exclusive right under a copyright in that work.”[173] The copyright holder can enforce his exclusive rights even if VARA rights are not enforceable.

Moreover, despite the ruling in English, artists may still have two types of claims under VARA:

1. Claims of Attribution over the Work

Artists could still enforce their VARA right of attribution over the original work. Since this right is not directly linked to the tangible aspect of the work, it is not pre-empted by an artist’s illegal acts.

Because graffiti artists do not have rights over the physical embodiment of their work, they lack the right to affix their name to the physical painting on the wall; but they should still be able to claim attribution in other ways, for instance, by preventing others from claiming that they produced the work.

Artists could still enforce a claim of attribution against any offenders, including the owner of the wall in some cases. Artists may not prevent wall-owners from erasing their signature on the wall, but they can still prevent owners from claiming that they authored the work. Because the owner made no authorial contribution to the work, they cannot claim authorship.

Some have argued that graffiti artists would be unlikely to claim attribution, as doing so might draw unwanted attention from police and ultimately lead to criminal liability.[174] This may not be the case, however, because the life of VARA rights and the statute of limitations for VARA infringements may be longer than the statute of limitations for graffiti penalties.[175] Therefore, an artist might claim attribution without fearing prosecution.

2. Claims against Third Parties to Protect the Integrity of the Work and to Prevent Destruction of the Work

Graffiti artists could still enforce their VARA rights against third parties who have no rights in the physical property.[176] By painting illegally on the city’s property, the plaintiffs in English did not forfeit their VARA rights. Instead, they simply could not enforce them against the city (the victim of their illegal paintings) due to the unclean hands doctrine. However, the doctrine of unclean hands would not apply towards unaffected third parties, because the artists did nothing wrong towards them. Thus, VARA rights should remain fully applicable against third parties.

In other words, although VARA rights to the integrity of a work and against destruction would not be enforceable against the owner of the property, they could be enforced against everyone else, such as bystanders who paint over a work or destroy it, including José Carlos Martinat.[177]

However, in the context of graffiti, it is worth noting some factors that may prevent application of the VARA rights of integrity and against destruction to third parties.

The right to integrity is shaped by the graffiti community’s codes of honor and reputation. Artists generally know that their work might be ephemeral and that someone else could paint the wall with other art or bring the wall back to its original state.[178] Some artistic modifications of the work are foreseen and expected by graffiti artists, and as such, might not implicate the artist’s right of integrity.[179]

The rules of the graffiti community can help us evaluate whether a modification affects the honor and reputation of the artist or not. For example, if an artist responds to overlapping graffiti on his work with a new graffiti (she does not just restore the original work, but she creates a new work in response to the intervention), then its reasonable to think that there is an artistic dialogue and that the modification of the work does not “prejudice the author’s honor or reputation,” because modifications are understood to be an element of graffiti art.[180]

The VARA right against destruction of a work, may be difficult for graffiti artists to use, as it only applies to works of “recognized stature.”[181] It may be difficult for many graffiti works to qualify for this status. Courts have interpreted the recognized stature requirement as a two-tiered standard, which demands: “(1) that the visual art in question has ‘stature’ i.e. is viewed as meritorious, and (2) that this stature is ‘recognized’ by art experts, other members of the artistic community, or by some cross-section of society.”[182] In graffiti art, this requirement was met in one case where the work was “a community work that exhibits the concerns of the community.”[183] The accepted work was a mural containing anti-drug, anti-alcohol and anti-smoking messages.[184] However, it is uncertain that the requirement would be met with regular street art that has no communitarian educational message in particular, or that was created by less than well-known artists. Some pieces by well-known graffiti artists would probably fulfill the recognized stature requirement without any communitarian or educational message because art experts, other members of the artistic community, and society as a whole recognize their stature.[185] However, works by less-famous artists may have more difficulty meeting the recognized stature standard.[186] This uncertainty is of real concern to artists who must embark on extensive legal research before litigation.[187]

Conclusion

In this article, I have argued that graffiti can and should be protected under copyright law. When an unauthorized graffiti work complies with the minimum requirements for copyright protection it should be protected under copyright law despite its illegality. This is because copyright should be neutral towards works created by illegal means. Copyright assigns rights over the intangible aspects of a work only; it does not exclude works that have been tangibly fixed in an illegal manner. This is true even under an incentive-based copyright system such as the one established by the United States Copyright Act. Illegal graffiti works are creative acts that comply with copyright’s goal of “promoting the Progress of Science and useful Arts.”[188] Protecting graffiti, moreover, may have the consequence of incentivizing graffiti artists to create more legal works.

I have also explored the challenges that artists face when enforcing rights over their graffiti, both under the Copyright Act and VARA. Graffiti has a unique position in relation to copyright’s nature and scope.

While “many people are too quick to view street art through the lens of vandalism,”[189] copyright law cannot simply dismiss graffiti works. Graffiti works must be treated on equal footing with other artistic works for the purposes of copyright law, without being discriminated against due to their illegality. Copyright protection is valuable to all graffiti artists since it gives them the ability to assert artistic control over how their works are reproduced and shared. It may be true that copyright is for losers, as Banksy has expressed.[190] But even if that is the case, graffiti artists should still have the option to be losers.

[1] This article focuses on United States copyright law. Many international examples will be used throughout this paper; however, they are used only as illustrative fact patterns, and all legal issues should ultimately be interpreted under US copyright law.

[2] U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 8.

[3] “Never before have we seen public art reach such a scale as we now see with the works of Blu, or become so pervasive as we see with Shepard Fairey’s, or so copied as that of Banksy, or so delicate as that of Swoon.” See Marc & Sara Schiller, Preface to Carlo McCormick et al., Trespass: A History Of Uncommissioned Urban Art 10 (Ethel Seno ed., 2010).

[4] See Magda Danysz & Mary-Noëlle Dana, From Style Writing To Art: A Street Art Anthology 18 (2011); see also Anna Waclawek, Graffiti and Street Art (2011) (surveying graffiti’s evolution).

[5] Lisa Gottlieb, Graffiti Art Styles: A Classification System And Theoretical Analysis 49 (2008).

[6] Even though many artists prefer to distance themselves from this word due to its illegal connotations, using this single term simplifies the analysis. I follow the practice of other writers who analyze graffiti art. See, e.g., Nicholas Ganz, Graffiti World 10 (Tristan Manco ed., 2004).

[7] “Letters used to dominate but today the culture has expanded: new forms are explored, and characters, symbols and abstractions have begun to proliferate.” Id. at 7.

[8] Graffiti: (Top left) King157, Oakland Graffiti Art (2008), Flickr, http://www.flickr.com/photos/24293932@N00/3302255569 (photograph by Anarchosyn (2009)); (Top center) A Graffiti Mecca on Borrowed Time, N.Y. Times (Aug. 28, 2011), http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2011/08/28/

nyregion/20110828POINTZss-6.html?_r=0 (photograph by Todd Heisler/N.Y. Times); (Top right) Graffiti in Derby, UK, Flickr, http://www.flickr.com/photos/orangeacid/180986272/ (photograph by Orangeacid (2006)); (Bottom) Graffiti Mecca, supra, http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2011/08/28/nyregion/20110828POINTZss-4.html (photograph by Todd Heisler/N.Y. Times).

[10] Id. at 19.

[11] Street art: (Top) Dave the Chimp, Human Beins (2009) in Christian Hundertmark, The Art Of Rebellion III: The Book About Street Art 54 (2010); (Bottom Left) L’Atlas, Gaffer Tape on Concrete (2010) id. at 15; (Bottom Right) Chu & Tec, Efectos Colaterales del Tamiflu [Side Effects of Tamiflu] (2009), Flickr, http://www.flickr.com/photos/tectec/3882199518/in/pool-64973255@N00/.

[12] Even when replicated, it could be argued that there is uniqueness to each piece, despite the stencil mechanism. Stencil is an artisanal painting method, not a mechanical one.

[13] Stencil: (Left) Graffitimundo, http://graffitimundo.com (last visited Mar. 15, 2013) (sixth photograph in the homepage slideshow); (Center) Banksy, Flower Thrower; (Right) Stencil Land, Metal Gaucho, Graffitimundo, http://graffitimundo.com/artists/stencil-land/ (last visited Mar. 15, 2013).

[14] Recently, for example, Stephan Keszler’s Gallery in the Hamptons has had street art works appraised for $200,000. Anny Shaw, Banksy Murals Prove To Be an Attribution Minefield, The Art Newspaper (February 16, 2012) [hereinafter, Banksy Murals], available at http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/Banksy-murals-prove-to-be-a-minefield/25631. Banksy’s graffiti art has been sold in the United Kingdom for £200,000. Wall Painted by Banksy Sells for £200,000 – but the New Owner Must Also Fork Out To Move the Brick Canvas, MailOnline (Jan. 15, 2008, 9:16 AM) [hereinafter “Wall Painted”], http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-508290/Wall-painted-Banksy-sells-200-000–new-owner-fork-brick-canvas.html. In the film Exit Through the Gift Shop (Paranoid Pictures 2010), the narrator mentions, “Now, no serious contemporary art collection would be complete without a Banksy.”

[15] See David Cameron Presents Barack Obama with Graffiti Art, BBC News (July 21, 2010, 5:25 AM), http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-10710074.

[16] An exhibition in Bristol by graffiti artist Banksy was among the top 30 most visited global exhibitions in the period 2008–2009. See Banksy Graffiti Works Enter World Exhibition Top 30, BBC News (Mar. 31, 2010, 2:02 AM), http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/8595341.stm. A group of artists is planning a new International Street Art Museum in Los Angeles. See Museum of International Street Art, http://www.internationalstreetart.org/

index.html (last visited Feb. 22, 2013).

[17] See, e.g., Ganz, supra note 5; Roger Gastman & Caleb Neelon, The History of American Graffiti (2011); Hundertmark, supra, note 11; Riikka Kuittinen, Street Art: Contemporary Prints (2010); Jaime Rojo & Steven P. Harrington, Street Art New York (2010); see also Ket, Street Art: The Best Urban Art from Around the World (2011); Alain Maridueña, New York City: Black Book Masters (2009); Eleanor Mathieson & Xavier A. Tàpies, Street Artists: The Complete Guide (2009); Style Needs No Color, Schwarz Auf Weiss (2009); Guilherme Zauith & Matt Fox-Tucker, Textura Dos: Buenos Aires Street Art (2010).

[18] Peter Rosenstein with text by Isabel Bau Madden, Tattooed Walls (2006).

[19] See David Gonzalez, Walls of Art for Everyone, but Made by Not Just Anyone, N.Y. Times, June 4, 2007, at B1, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/04/nyregion/04citywide.html?sq=walls%20of%20art&st=nyt&scp=1&pagewanted=all&_r=0.

[20] Id.

[21] Id.

[24] Villa v. Brady Publ’g, No. 02 C 570, 2002 WL 1400345, at *1 (N.D. Ill. June 27, 2002).

[25] Id. at *3.

[26] Villa v. Pearson Educ., No. 03 C 3717, 2003 WL 22922178, at *1 (N.D. Ill. Dec. 9, 2003).

[27] E-mail from Hiram Villa. Pres., Momentum Art Tech., to Celia Lerman, Visiting IP Scholar, Kernochan Center for Law, Media & the Arts, Columbia Law School (Feb. 8, 2012) (on file with author).

[28] Hrag Vartanian, Street Artist Triumphs Over Urban Outfitters in Copyright Case, Hyperallergic (Sept. 20, 2011), http://hyperallergic.com/36016/

cali-killa-urban-outfitters/.

[29] Id.

[30] Markus Balser, Cantwo Says “Can Not!” to Spanish Swimmers, Wall St. J. (Sept. 9, 2008, 4:44 PM), http://blogs.wsj.com/law/2008/09/09/

cantwo-says-can-not-to-spanish-swimwear/.

[31] Id.

[32] He told the Wall Street Journal: “Despite some color changes: To my mind the cartoon-style character was clearly taken from an artwork I sprayed on a wall legally in Muenster in 2001. [. . .] I have absolutely no idea how this Graffiti made its way to the Olympic stage, but I know: I can’t accept that somebody is copying my work, the work I have to live on.” Id.

[33] See Dean R. Karau, Will Spain’s Olympic Synchronized Swim Team Be Sunk by German Graffiti Artist?, Fredrikson & Byron P.A. (Sept. 2008) http://www.fredlaw.com/areas/trademark/Articles/trade_0809_drk1.html.

[34] See David Gonzalez, Graffiti Muralists Reach Settlement in Case of Contentious Fiat 500 Commercial, N.Y. Times, (Dec. 2, 2011, 6:00 AM), http://wheels.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/12/02/graffiti-muralists-reach-settlement-in-case-of-contentious-fiat-500-commercial/.

[35] Karen McVeigh, 5Pointz: New Yorkers Prepare To Say Goodbye To a Slice of Hip-Hop History, Guardian (Jan. 17, 2012, 12:43 PM), http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/jan/17/5pointz-new-york-hip-hop-history.

[36] “‘This is a cultural landmark, not only for New York, but for hip-hop culture worldwide’ says Steve Harrington, the author of the book Street Art New York. . . .‘We need to keep our cultural institutions protected and preserved.’” Marlon Bishop, Queens Graffiti Mecca Faces Redevelopment, W.N.Y.C. (Mar. 7, 2011), http://culture.wnyc.org/articles/features/2011/mar/07/queens-graffiti-mecca-faces-redevelopment/; see also Robin Finn, Writing’s on the Wall (Art Is, Too, for Now), N.Y. Times, Aug. 27, 2011, at MB1, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/28/nyregion/5pointz-arts-center-and-its-graffiti-is-on-borrowed-time.html?pagewanted=all.

[37] Clem Richardson, Word on His Street Is Art Businessman Offers Artists a Place To Create Murals, N.Y. Daily News (June 5, 2000, 12:00 AM), http://www.nydailynews.com/archives/boroughs/word-street-art-businessman-offers-artists-place-create-murals-article-1.875235.

[38] McVeigh, supra note 35; Averie Timm, Owner Says Queens Graffiti Mecca 5Pointz Will Stay for Now, but Not Forever, Village Voice (Apr. 8, 2011, 5:11 PM), http://blogs.villagevoice.com/runninscared/2011/04/5pointz_owner_interview.php.

[39] To see the online petition, go to http://www.ipetitions.com/petition/support5pointz/signatures.

[40] See N.Y. Penal Law § 145.60 (McKinney 1992), which bars the making of graffiti without “the express permission of the owner or operator” of the property. See also N.Y. City Admin. Code § 10-117 (McKinney 2006) which is the municipal regulation barring graffiti without the “express permission of owner or operator of the property.”

[41] See infra Part III.A. Unfortunately, given the confidential nature of the matter, I was unable to obtain more details regarding Wilkoff’s consent and the relationship between Wilkoff and Meres One during my visit to 5Pointz in January 2012.

[42] See Claudio Iglesias, Pared Contra Pared [Wall Against Wall], Página/12 (Nov. 14, 2010), http://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/suplementos/radar/

9-6612-2010-11-14.html.

[43] See Paredes Robadas: Street Art Theft in Buenos Aires, Graffitimundo (Oct. 15, 2011), http://graffitimundo.com/media/paredes-robadas-the-theft-of-buenos-aires-street-art.

[44] Id.

[45] See id.

[46] See id.

[47] Interview with Jonny Robson, Co-Founder, Graffitimundo, in Buenos Aires, Arg. (December, 2011). Graffitimundo is an organization dedicated to increasing awareness of the rich heritage and dynamic culture of street art, based in Buenos Aires. See About Us, Graffitimundo, http://graffitimundo.com/about-us/ (last visited April 6, 2013).

[49] Id.

[50] See N.Y. Penal Code § 145.60 (McKinney 2012) (“1. For the purposes of this section, the term “graffiti” shall mean the etching, painting, covering, drawing upon or otherwise placing of a mark upon public or private property with intent to damage such property. 2. No person shall make graffiti of any type on any building, public or private, or any other property real or personal owned by any person, firm or corporation or any public agency or instrumentality, without the express permission of the owner or operator of said property. Making graffiti is a class A misdemeanor.”). Other states such as California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Utah and Washington also criminalize graffiti activity. See Ralph E. Lerner & Judith Bresler, Art Law: The Guide for Collectors, Investors, Dealers, and Artists 947 (2005).

[51] See N.Y. Penal Code § 145.65 (McKinney 2012).

[52] See N.Y. City Admin. Code § 10-117 (2012) (on the defacement of property, possession, sale and display of aerosol spray paint cans, [and] broad tipped markers and etching acid prohibited in certain instances). See also L.A., Cal., Mun. Code ch. 1 § 47.11; Cal. Penal Code § 594; Colo. Rev. Mun. Code § 34-66.

[53] 17 U.S.C § 102a (2013).

[54] See Arthur Miller & Michael H. Davis, Intellectual Property in a Nutshell 294 (2000).

[55] 17 U.S.C. §101 provides that a work is fixed “when its embodiment [. . .] by or under the authority of the author, is sufficiently permanent or stable to permit it to be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated for a period of more than transitory duration.”

[56] Keith Haring started his career painting illegal art in the New York subways from 1980 to 1985. See About Haring, The Keith Haring Foundation, http://www.haring.com/about_haring/bio/index.html (last visited April 6, 2013).

[57] Id.

[58] As per 37 C.F.R. § 201.1(a), “Words and short phrases such as names, titles, and slogans; familiar symbols or designs; mere variations of typographic ornamentation, lettering or coloring; mere listing of ingredients or contents” are not protected under copyright. It should be noted, however, that even despite not being protected by copyright, signatures could potentially be protected by other rules such as trademark law. See Justin Hughes, Size Matters (or Should) in Copyright Law, 74 Fordham L. Rev. 575, 583 (2005) (noting courts have given small pieces of expression intellectual property protection).

[59] 37 C.F.R. § 201.1.(e) establishes: “The following are examples of works not subject to copyright and applications for registration of such works cannot be entertained: [. . .] (e) Typeface as typeface.” See also Eltra Corp. v. Ringer, 579 F.2d 294 (4th Cir. 1978) (holding that the design submitted did not qualify as a “work of art” under the Copyright Law.

[60] Graffiti (left to right): Paul Insect (2008), Banksy (2011).

[61] See 17 U.S.C. § 101 (defining “fixation”).

[62] A period more than transitory duration needs not be more than a few minutes. See Advanced Computer Servs. of Mich., Inc. v. MAI Sys. Corp., 845 F. Supp. 356, (E.D. Va. 1994) (finding that a “random access memory (RAM) representation of copyrighted computer software program is sufficiently ‘fixed’ to be a ‘copy’ protected by Copyright Act when program is loaded from computer’s hard drive to RAM and maintained there for minutes or longer, even though RAM representation of program disappears when the computer is turned off”).

[63] Under 17 U.S.C. § 101, A “work of visual art” is—

(1) a painting, drawing, print, or sculpture, existing in a single copy, in a limited edition of 200 copies or fewer that are signed and consecutively numbered by the author, or, in the case of a sculpture, in multiple cast, carved, or fabricated sculptures of 200 or fewer that are consecutively numbered by the author and bear the signature or other identifying mark of the author; or

(2) a still photographic image produced for exhibition purposes only, existing in a single copy that is signed by the author, or in a limited edition of 200 copies or fewer that are signed and consecutively numbered by the author.

A work of visual art does not include–

(A)

(i) any poster, map, globe, chart, technical drawing, diagram, model, applied art, motion picture or other audiovisual work, book, magazine, newspaper, periodical, data base, electronic information service, electronic publication, or similar publication;

(ii) any merchandising item or advertising, promotional, descriptive, covering, or packaging material or container;

(iii) any portion or part of any item described in clause (i) or (ii);

(B) any work made for hire; or

(C) any work not subject to copyright protection under this title.

[64] See §101.

[65] Under §101, paintings and drawings should be signed and numbered to be considered a “work of visual art,” and that sculptures should be numbered and bear the signature or other identifying mark of the author.” § 101(1).

[66] Id.

[67] Id. (listing visual forms of art—painting, drawing, print, or sculpture).

[68] Article I, Section 8, Clause 8 of the United States Constitution grants authors the exclusive right to their respective writings. It is codified in 17 U.S.C. § 201(a).

[69] See § 202 (“Ownership of a copyright, or of any of the exclusive rights under a copyright, is distinct from ownership of any material object in which the work is embodied. . . . ”). See also Forward v. Thorogood, 985 F.2d 604 (1st Cir. 1993).

[71] See Banksy Graffiti Can Push Up Property Price, The Sun (October 20, 2010), available at http://www.thesun.co.uk/sol/homepage/features/

3187949/Banksy-graffiti-can-push-up-property-price.html.

[72] If the graffiti is sold, graffiti artists could potentially benefit from the value they add to others’ property by the doctrine of accession, under which one who has “taken the property of another, and altered it in substance of form by his own labor” that “results in a change in the identity or an increase in the value of the property, the right to the property in its changed condition” may belong to the improver. See American Jurisprudence 2D, Accession and Confusion §1. I thank Columbia Law School students Laura Mergenthal and Jessica Fjeld for this observation. Nevertheless, this doctrine would rarely apply to graffiti, since graffiti is normally not done in good faith and it does not transform the substance of the property to which it is applied.

[73] However, in Los Angeles it is against zoning laws to create graffiti murals even with authorization and on private property. See L.A., Cal. Mun. Code ch. 1 §§ 14.4.2, 14.4.4, 14.4.20, 19.01. These regulations could be considered an unreasonable restriction of the property owner’s rights, and there are local efforts to obtain their repeal. See Los Angeles Mural Ordinance Would Legalize New & Vintage Murals, Huffington Post (December 8, 2011, 6:15 PM), http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/12/08/los-angeles-mural-ordinance_n_1137746.html&ei=RTFcT7rlBdObtwec36WFDA&usg=

AFQjCNFn7r7x0BX0gqFXgGojHYecCMM-Mg.

[74] One controversial example involving Banksy is his depiction of “a woman in underwear, her jealous husband, and her naked lover dangling from a window ledge,” painted on the wall of a clinic for venereal diseases in Bristol, United Kingdom. The clinic decided to keep the artwork, after a poll conducted by the Bristol City Council in which 93% of people voted in favor of the painting’s preservation. See Arifa Akbar, Art Or Eyesore? Public Asked If Banksy’s Mural Should Stay, The Independent, (June 23, 2006), available at http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/this-britain/art-or-eyesore-public-asked-if-banksys-mural-should-stay-405119.html.

[75] Keith Haring illegally painted the “Crack is Wack” mural in a plaza in Harlem, New York City. After Haring’s death, the New York City government embraced the mural and the plaza was renamed “the Crack is Wack Playground.” For a description of the park, see Crack is Wack Playground Highlights, N.Y.C. Parks, http://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/M208E/history (last visited April 6, 2013).

[76] See Wall Painted, supra note 14 (noting wall painted by Banksy sold for £200,000); Liza Ghorbani, The Devil on the Door: Could a Painting on a Dope Dealer’s Storefront Be the Last Work of Jean-Michel Basquiat?, N.Y. Mag. (Sept. 18, 2011) (describing Jean-Michele Basquiat’s door), available at http://nymag.com/arts/art/features/jean-michel-basquiat-2011-9/.

[77] As noted above, New York defines the offense of graffiti: “No person shall make graffiti of any type on any building, public or private, or any other property real or personal owned by any person, firm or corporation or any public agency or instrumentality, without the express permission of the owner or operator of said property.” N.Y. Penal Code § 145.60 (McKinney 2013). Upon first impression, the statute would not appear to permit ex post acceptance. However, as noted elsewhere in this piece, prosecutors would be unlikely to press charges when the victim welcomes the supposed intrusion.

[78] See Baumgart v. Spierings, 86 N.W.2d 413, 415 (WI 1957). Acceptance from the owner could be analogous to “implied consent to trespass,” as a physical analog. Implied consent to trespass occurs when the subject reasonably believes that the property is open to public.

[79] See J. Tony Serra, Graffiti and U.S. Law, in McCormick, supra note 3, at 313; see also L. L. Hanesworth, Are They Graffiti Artists or Vandals? Should They Be Able or Caned?: A Look at the Latest Legislative Attempts to Eradicate Graffiti, 6 DePaul J. Art & Ent. Law 225 (1995–1996); Kelly P. Welch, Graffiti And The Constitution: A First Amendment Analysis Of The Los Angeles Tagging Crew Injunction, 85 S. Cal. L. Rev. 205 (2011). In a separate but related line of arguments, other scholars have justified graffiti as a minor form of rebellion against an unjust government, according to a just war theory criterion. See Daniel J. D’Amico & Walter Block, A Legal And Economic Analysis Of Graffiti, in 23 Humanomics no. 1, 2007, at 29.

[80] Consider political or activist paintings under an oppressive regime, such as the paintings of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo in the Plaza de Mayo square in Argentina, a sign of protest and remembrance for their children who went missing during the “dirty war.” The paintings have been regarded as legal, given their ties to freedom of speech, and were protected against later overlapping paintings by relatives of military members. See Cruces entre Madres y Pando por las pintadas en la Plaza, Infobae, http://www.infobae.com/politica/368805-0-0-Cruces-Madres-y-Pando-las-pintadas-la-Plaza (last visited April 7, 2013).

Also, consider the use of Pixação in Brazil during its military dictatorship in the 1980’s. Pixação is a distinct type of graffiti art that developed in the poor neighborhoods of São Paulo as part of a social protest towards the dictatorship’s economic regime. It was pervasive and actively combated by the Brazilian government. See Simon Romero, At War With São Paulo’s Establishment, Black Paint in Hand, N.Y. Times, January 28, 2012, at A5; François Chastanet, Pixação: São Paulo Signature (2007).

[81] 466 U.S. 789 (1984).

[82] Id. at 806–807 (citing Metromedia, Inc. v. San Diego, 453 U.S. 490, 507–508 (1981) (White, J., plurality opinion)).

[83] See United States v. O’Brien, 391 U.S. 367, 376 (1968). Freedom of speech may be ineffective against anti-graffiti laws if it is considered that these laws may “further[] . . . important or substantial governmental interests,” and those interests are “unrelated to suppression of free expression,” id. at 377; and “the incidental restriction on alleged First Amendment freedom is no greater than is essential to furtherance of that interest.” Id.

[84] Clark v. Cmty. for Creative Non-Violence, 468 U.S. 288, 293 (1984).

[86] 847 F.2d 1045 (2d Cir. 1988).

[87] Id. at 1048.

[88] Id. at 1047. The decision to remove the sculpture was made after a public hearing in which artists, civil leaders, employees at the Federal Plaza complex, and community residents participated. Id.

[89] Id.

[90] Id. at 1049.

[91] Id. at 1045. The court decided to remove the sculpture “[n]otwithstanding that the sculpture is site-specific and may lose its artistic value if relocated.” Id. at 1050.

[92] The law “refuses to lend its aid in any manner to one . . . who has been guilty of unlawful or inequitable conduct in the matter,” because the law seeks to “prevent a party from taking advantage of its own wrong.” 30A C.J.S. Equity § 109 (2013).