Download a PDF version of this article here.

By Joanna Shepherd*

Introduction

Inter partes review (IPR), a new pathway for challenging patents, is threatening the nature of competition in the pharmaceutical industry, drug innovation, and consumers’ access to life-improving drugs. Since its creation under the America Invents Act (AIA) in 2012,[1] this new administrative proceeding has produced noticeably anti-patent results. Whereas patents challenged in district court are invalidated in less than 40% of cases,[2] and patents challenged in the administrative predecessors of IPR were invalidated in less than one-third of cases, IPRs have resulted in patent invalidations in a shocking 70% of cases.[3] Moreover, the IPR process has been exploited by entities that would never be granted standing in traditional patent litigation—hedge funds betting against a company, then filing an IPR challenge in hopes of crashing the stock and profiting from the bet.[4]

Unfortunately, in recent decisions, courts have recognized the anti-patentee bias of IPR, yet punted to Congress the job of amending the provisions. In Cuozzo Speed Technologies v. Lee (Cuozzo) in June 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court found that an anti-patentee claim construction standard in IPR “increases the possibility that the examiner will find the claim too broad (and deny it),”[5] yet concluded that only Congress could mandate a specific standard.[6] Similarly, in Merck & Cie v. Gnosis in April 2016, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit determined that an anti-patentee standard of review for IPR decisions “is seemingly inconsistent with the purpose and content of the AIA,”[7] yet decided that “the question is one for Congress.”[8] On the standing issue, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) concluded in 2015 that, under the AIA language created by Congress, hedge funds cannot be excluded from IPR proceedings.[9]

Congress generally intended IPR to improve patent quality by providing a more efficient pathway to challenge patents of dubious quality. Because IPR is available for patents in any industry, for pharmaceutical patents, IPR offers an alternative to the litigation pathway that Congress specifically created over three decades ago in the Hatch-Waxman Act. With Hatch-Waxman, Congress sought to achieve a delicate balance between stimulating innovation from brand companies who hold patents and facilitating market entry from generic companies who challenge the patents. By all accounts, Hatch-Waxman has successfully achieved these goals. Generic drugs now account for 89% of drugs dispensed,[10] yet brand companies still invest significantly in R&D, which accounts for over 90% of the spending on the clinical trials necessary to bring new drugs to market.[11]

Unfortunately, IPR proceedings that culminate in a PTAB trial differ significantly from Hatch-Waxman litigation that occurs in federal district court. The PTAB applies a lower standard of proof for invalidity than do district courts in Hatch-Waxman litigation. It is also easier to meet the standard of proof in a PTAB trial because there is a more lenient claim construction standard and a substantially limited ability to amend patent claims. Moreover, on appeal, PTAB decisions in IPR proceedings are given more deference than lower district court decisions. Finally, while patent challengers in district court must establish sufficient Article III standing, IPR proceedings do not have a standing requirement, allowing any member of the public other than the patent owner to initiate an IPR challenge. These inconsistencies have led to the significantly different patent invalidation rates in PTAB trials compared to rates in district court litigation.

It is imperative that Congress reduce the disparities between IPR proceedings and Hatch-Waxman litigation. The high patent invalidation rate in IPR proceedings creates significant uncertainty in pharmaceutical intellectual property rights. Uncertain patent rights will, in turn, lead to less innovation in the pharmaceutical industry. Drug companies will not spend the billions of dollars it typically costs to bring a new drug to market when they cannot be certain if the patents for that drug can withstand IPR proceedings that are clearly stacked against them. And if IPR causes drug innovation to decline, a significant body of research predicts that consumers’ health outcomes will suffer as a result.

This Article proceeds as follows. Section II begins with a general discussion of the pharmaceutical market, explaining the nature of competition between brand and generic drugs and the importance of brand drug innovation. Section III explains the regulatory frameworks that Congress established to balance the interests of brand patent holders with generic patent challengers, focusing on the Hatch-Waxman Act and the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act. Section IV describes administrative pathways available for patent challenges; it discusses both IPR’s predecessors and the changes introduced with IPR under the AIA. Section V explains the critical differences between district court litigation in Hatch-Waxman litigation and IPR proceedings that give rise to the pro-challenger bias in IPR. Section VI proposes several reforms that Congress could institute to align IPR with Hatch-Waxman and restore the delicate balance between stimulating innovation and encouraging generic entry. Section VII concludes the Article.

I. Understanding the Pharmaceutical Market

A. The Nature of Competition Between Brand and Generic Drugs

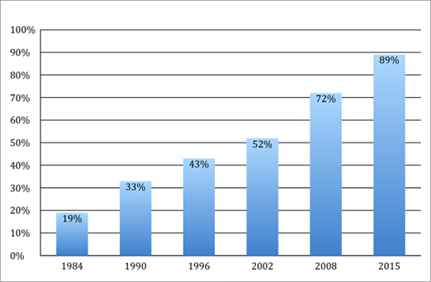

Over the past several decades, the nature of competition in the pharmaceutical industry and the relative market shares of brand and generic companies have changed dramatically. The generic industry exploded after the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act—discussed in greater detail in Section III—created various regulatory shortcuts and litigation incentives to spur the introduction of generic alternatives to brand name drugs. The generic industry was further assisted by drug substitution laws in every state that allowed, or sometimes required, pharmacists to automatically substitute a generic equivalent drug when a patient presents a prescription for a brand drug. These regulatory changes have allowed generics to capture significant market share from brand companies. As shown in Figure 1, generics’ market share has steadily increased from only 19% of drugs dispensed in 1984 to nearly 89% in 2015.

The success of generic drugs can be attributed entirely to their lower prices. When a brand drug’s patent expires, generics initially enter the market at a price that is, on average, 50% less than their branded counterpart.[13] As months pass and more generics enter the market, the generic price eventually drops to 80% of the pre-expiry brand drug’s price. Generic companies are able to charge these lower prices while earning substantial profits because they face significantly lower costs than brand drug companies. In contrast to brand companies that spend an average of $2.6 billion on R&D and the FDA approval process, bringing a new generic drug to market costs only $1 to $2 million.[14] In addition, whereas brand companies spend millions of dollars marketing their drugs to physicians and patients,[15] generic companies typically spend very little on marketing. Because generics are automatically substituted for brand prescriptions at the pharmacy, generics can free-ride on the marketing efforts of brand companies and rely on automatic substitution laws for a large chunk of their sales. With these significantly lower costs, generic companies can afford to charge a lower price for their drugs and still earn impressive profits.

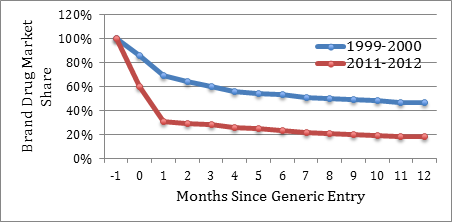

A significant number of existing brand drug customers switch to the lower-priced generics as they enter the market, swiftly eroding brand drugs’ market share. As shown in Figure 2, upon market entry, generics now routinely capture over 70% of the brand drug’s market share within only three months of generic entry. In contrast, as recently as 1999, generics captured less than 40% of the market within three months. Within twelve months, generics now capture over 80% of the brand drug’s market share, whereas in 1999, they only captured slightly over 50%.

The expansion of the generic industry has produced significant savings for consumers; in the last decade alone, generic drugs have saved the healthcare system nearly $1.7 trillion dollars.[17] However, it has also raised concerns about brand companies’ ability to develop innovative new drugs. Brand drugs experience a significant drop in sales after generics enter the market and erode brand market share. For instance, in 1984 new brand drugs experienced a 12% decrease in net sales as a result of generic entry (a decrease which took place during the first decade after the enactment of the Hatch-Waxman Act).[18] And the expansion of generic drugs since then has further reduced brand sales. Brand drugs’ average lifetime sales are now lower than they were in the early 1990s.[19] In fact, just two in ten brand drugs now earn profits sufficient to cover the average R&D costs required to bring new drugs to market.[20] Moreover, between 2012 and 2018, it is estimated that brand drug companies will lose almost $150 billion in sales because of patent expirations and generic entry.[21]

B. The Importance of Brand Drug Innovation

Unfortunately, reductions in brand drugs’ profitability limits companies’ ability and incentive to engage in the expensive R&D necessary to develop innovative new products. Drug companies will not spend millions (or potentially billions) of dollars to develop new drugs if they cannot recoup (and earn an acceptable return on) the costs of said development. Moreover, since only 20% of marketed brand drugs will ever earn enough sales to cover their development costs, the sales of these successful drugs must not just recoup their own costs; they must also cover the costs of the other 80% of approved drugs that generate losses for drug makers.[22]

Less R&D spending by brand companies will result in less innovation throughout the pharmaceutical industry. Brand drug companies are largely responsible for pharmaceutical innovation.[23] Since 2000, brand companies have spent over half a trillion dollars on R&D,[24] and they currently account for over 90% of the spending on the clinical trials necessary to bring new drugs to market.[25] Because of this spending, over 550 new drugs have been approved by the FDA since 2000,[26] and another 7,000 are currently in development globally.[27] Yet brand companies’ R&D efforts and innovation are directly tied to their profitability. Numerous studies have found that policies that increase pharmaceutical profitability lead to increases in new clinical trials, new molecular entities, and new drug offerings.[28] Other studies have found that policies that reduce expected profitability lead to decreases in R&D spending.[29] Thus, reductions in brand drug profitability over the long term could very well lead to less R&D and less innovation in the pharmaceutical market.

A reduction in innovation will jeopardize the significant health advances that innovation achieves. Empirical estimates of the benefits of pharmaceutical innovation indicate that each new drug brought to market saves 11,200 life-years each year.[30] Another study finds that the health improvements from each new drug can eliminate $19 billion in lost wages by preventing lost work due to illness.[31] Moreover, because new, effective drugs reduce medical spending on doctor visits, hospitalizations, and other medical procedures, data shows that for every additional dollar spent on new drugs, total medical spending decreases by more than seven dollars.[32] Brand companies, and the profit incentives that motivate them, are largely responsible for pharmaceutical innovation. Thus, actions that reduce brand profitability could have long-term negative effects on consumer health and health care spending.

II. Regulatory Frameworks Balancing Drug Innovation with Generic Availability

Understanding the importance of stimulating innovation while encouraging generic entry, Congress created two regulatory frameworks that balanced the interests of brand patent holders with generic patent challengers. The Hatch-Waxman Act applies to traditional drugs, while the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act covers the new pathway for follow-on biologic drugs. This section discusses both regulations in turn.

A. The Hatch-Waxman Act

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, was designed to balance the benefits of pharmaceutical innovation with consumers’ needs for affordable drugs.[33] With Hatch-Waxman, Congress recognized that drug companies will only have the incentive to innovate if they can earn sufficient profits during the patent period to recover the exorbitant costs of researching and developing the drug, obtaining FDA approval, and marketing the drug to physicians and patients. However, while preserving incentives for “brand-name” innovations, Hatch-Waxman also encourages companies to create bioequivalent drugs—generics—that copy these branded drugs and enter the market at a lower price as soon as the patents expire on the innovator drugs.[34]

Hatch-Waxman includes various provisions designed to incentivize innovation by brand drug companies. First, to help companies recover the costs of bringing a drug to market, Hatch-Waxman allows for an extension of the patent term lost because of delays attributable to the FDA approval process. It establishes a period of patent restoration, which extends a covered drug’s patent length by up to five years (to a maximum of fourteen years) for half of the brand drug’s clinical testing period and all time spent securing FDA approval.[35] In addition to patent term restoration, Hatch-Waxman confers on brand drugs five years of data exclusivity. Data exclusivity prohibits the FDA from receiving a generic application that relies on the brand drug’s safety and efficacy data. Protection from early generic filings helps to ensure that brand drug manufacturers have an adequate opportunity to recoup research, development and marketing costs.[36]

But in exchange for these new protections for brand drug manufacturers, Hatch-Waxman created various incentives for other companies to produce and market cheaper, generic drugs. First, to spur the introduction of low-cost generics, Hatch-Waxman created the Abbreviated New Drug Application (“ANDA”) process that allows a generic that demonstrates bioequivalence to rely on previously submitted brand drug safety and efficacy data.[37] Prior to Hatch-Waxman, generics were required to submit their own original safety and efficacy data, often duplicating the brand drugs’ tests. The new, greatly truncated process enables generics to quickly enter the market after brand patent expiration and to bring new drugs to market at a cost of only $1 to $2 million, compared to an average of $2.6 billion for brand drugs.[38] Moreover, Hatch-Waxman also immunizes generic companies from patent infringement liability for uses of the brand drug prior to expiration that are reasonably related to the filing of an FDA application.[39]

Second, Hatch-Waxman actively incentivizes generic companies to challenge the validity of brand patents before they expire by creating a pathway for such challenges and by offering a lucrative incentive to the first generic manufacturer to do so. Under a “Paragraph IV” challenge, a generic manufacturer submits an ANDA certifying that either the brand drug patent is invalid or unenforceable, or the generic drug will not infringe on the listed brand patent. As an incentive for filing Paragraph IV challenges, for the first generic that files a challenge and wins, Hatch-Waxman grants a 180-day exclusivity period during which the FDA will not approve any other generic versions of the drug. During this period, the first generic is the only generic on the market, and it can earn substantial profits by shadow pricing, or pricing slightly under the innovator’s price.[40] As a result of this lucrative incentive, Paragraph IV challenges have exploded in recent years: although only 9% of drugs facing generic entry in 1995 were challenged, 81% of drugs facing generic entry in 2012 were challenged.[41] Moreover, Paragraph IV challenges are occurring earlier in the lives of brand drugs. Brand drugs that experienced their first generic entry in 1995 faced their first Paragraph IV challenge 18.7 years after original launch. By comparison, drugs facing the first generic entry in 2012 saw only 6.9 years between market launch and the first Paragraph IV challenge.[42]

Thus, Congress designed the Hatch-Waxman Act to strike a delicate balance between promoting brand innovation and facilitating generic entry. By granting brand drugs a period of patent restoration and data exclusivity, the Act recognized that brand innovators must earn a sufficient return on their R&D costs for innovation to occur. Yet, by streamlining the generic approval process, incentivizing generic challenge of brand patents and providing a litigation pathway for such challenges as discussed below, the Act also sought to increase generic availability and lower drug prices. By all accounts, Hatch-Waxman has successfully achieved these twin goals; generics now account for 89% of drugs dispensed,[43] yet brand companies still invest significantly in R&D, accounting for over 90% of the spending on clinical trials.[44]

B. The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act

Congress reconfirmed its intentions to balance brand innovation with the entry of cheaper, follow-on alternatives in 2009 with the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA).[45] The BPCIA deals with biologic drugs that distinguish themselves from traditional drugs by their origins: biologics derive from living organisms, typically proteins; though occasionally include toxins, blood, viruses or allergens.[46] These medications are far more complex than traditional medicines; whereas a traditional drug might contain between a few dozen to a hundred atoms per molecule, a biologic’s complicated proteins can include several thousand atoms per molecule.[47] Because of this complexity, biologics are significantly more expensive to manufacture than traditional drugs. The average cost of a biologic drug is twenty-two times greater than a traditional drug, making them prohibitively expensive for many consumers.[48]

Fortunately, Congress recognized the need for cheaper, follow-on substitutes for biologic drugs—or biosimilars (the generic counterpart of biologic drugs). With the BPCIA, it achieved a compromise between biologics and biosimilars patterned after Hatch-Waxman’s regulatory scheme for traditional drugs. First, the BPCIA created an expedited biosimilar approval pathway—analogous to Hatch-Waxman’s approval pathway for generic drugs—under which a proposed biologic substitute does not have to demonstrate bioequivalence, but merely biosimilarity, to a reference product.[49] A product approved as biosimilar may further be deemed “interchangeable” with another biologic if its manufacturer can demonstrate that switching between the reference biologic and the proposed substitute presents no additional risk in safety or efficacy for consumers.[50] Similar to Hatch-Waxman’s 180-day generic exclusivity window, the first biosimilar deemed interchangeable receives an exclusivity window as well.[51]

However, the BPCIA also recognizes the importance of protecting the original biologic’s patent period to encourage biologic innovation. Innovative biologics—the biologic equivalent of brand drugs—receive twelve years of marketing exclusivity during which the FDA cannot approve a biosimilar substitute. [52] The BPCIA also confers four years of data exclusivity on innovative biologics during which a biosimilar is not permitted to use a reference drug’s safety information to file an abbreviated application for FDA approval.[53]

Thus, like Hatch-Waxman’s balance between protecting brand innovation and encouraging generic entry, the BPCIA protects biologics’ patent terms while incentivizing biosimilar entry in the market.

C. Legal Challenges to Patents Under Hatch-Waxman and BPCIA

Both Hatch-Waxman and the BPCIA establish frameworks for patent challenges that further balance the competing interests of brand and generic drug manufacturers. As noted above, when an ANDA applicant makes a Paragraph IV certification that the brand patent is either invalid, unenforceable or would not be infringed by the generic drug, Hatch-Waxman provides a structure for resolving the dispute.[54] First, the ANDA filer must give notice to the brand patent holder of the Paragraph IV certification. Hatch-Waxman makes the filing of an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification an act of patent infringement even though no direct infringement has occurred. Thus, in contrast to many other industries in which the patent holder cannot sue for infringement until an infringing product has been produced and sold, the brand patent holder can bring suit against a generic rival before the infringing product is brought to market.[55] Moreover, the ANDA filer can resolve the patent dispute in court before exposing itself to patent infringement damages for bringing the challenged product to market. If the brand company does not sue for patent infringement within forty-five days of receiving notice of the Paragraph IV certification, the FDA may approve the ANDA and the ANDA filer can file for declaratory judgment of patent invalidity or noninfringement. If the brand company does sue for patent infringement within the forty-five days, the FDA is stayed from approving the generic ANDA until the generic company prevails in court or reaches a settlement, the brand patent expires, or a thirty-month stay expires. If the generic company wins at trial or reaches a favorable settlement, it receives a 180-day exclusivity period during which the FDA will not approve any other generic versions of the drug.

Similarly, the BPCIA creates a framework for patent challenges of biologic drugs that balances the interests of original biologics and biosimilars.[56] First, the biosimilar applicant must give notice to the biologic manufacturer that it plans to market a competing product, and it must provide access to the biosimilar application and relevant manufacturing details. Similar to a Paragraph IV filing under Hatch-Waxman, the BPCIA creates an artificial act of infringement that enables the original biologic manufacturer to bring a claim for patent infringement against a biosimilar manufacturer. If it chooses to bring an infringement claim, the original biologic manufacturer may provide to the biosimilar applicant a list of all patents it believes are infringed. The parties may then decide to exchange statements describing why each patent will or will not be infringed and negotiate as to which patents will be subject to the patent infringement action in the first round of litigation.[57] Unlike Hatch-Waxman, the BPCIA does not provide a stay of FDA approval during the course of patent litigation. However, by requiring the biosimilar applicant to give 180 days’ notice before going to market, the BPCIA does provide an opportunity for biologic manufacturers to seek a preliminary injunction against an “at-risk” launch (i.e., a launch while patent litigation is ongoing and there is a risk of incurring patent infringement damages) of the biosimilar. Furthermore, to encourage biosimilar development and patent challenges, the BPCIA grants an exclusivity period to the first interchangeable biosimilar that wins a patent dispute or is not sued for infringement.[58]

Thus, Hatch-Waxman and the BPCIA encourage generic and biosimilar manufacturers to challenge patents with a regulatory “bounty” system that provides a lucrative incentive for follow-on drug development and patent challenges. At the same time, they protect brand and biologic patent holders from generic/biosimilar competition in the marketplace until after a patent dispute has been resolved. Moreover, brand patent holders are afforded additional protections because federal district court is the venue for Hatch-Waxman and BPCIA patent challenges. The court presumes patents are valid unless a patent challenger can show invalidity by clear and convincing evidence. In addition, the court interprets patent claims using the “ordinary and customary meaning” standard, making invalidation less likely than under the more lenient standard used in administrative proceedings.[59]

III. Administrative Proceedings for Patent Challenges

A. Pre-IPR Proceedings

In addition to the litigation frameworks created under Hatch-Waxman and the BPCIA, patents can also be challenged in administrative proceedings. Congress has long recognized that imperfections exist in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) examination and issuance process and that some issued patents may require reexamination.[60] In creating an administrative pathway for patent reexamination, Congress intended to reduce both the number of doubtful patents and the cost of patent litigation.[61] This “second look” allows the PTO to withdraw improperly granted patents, thereby correcting its previous errors at a much lower cost than litigation. Indeed, Congress predicted that the administrative reexamination of doubtful patents would:

permit efficient resolution of questions about the validity of issued patents without recourse to expensive and lengthy infringement litigation. This, in turn, will promote industrial innovation by assuring the kind of certainty about patent validity which is a necessary ingredient of sound investment decisions. . . . A new patent reexamination procedure is needed to permit the owner of a patent to have the validity of his patent tested in the Patent Office where the most expert opinions exist and at a much reduced cost. Patent office reexamination will greatly reduce, if not end, the threat of legal costs being used to ‘blackmail’ such holders into allowing patent infringements or being forced to license their patents for nominal fees.[62]

Prior to the AIA in 2012, these administrative reexamination proceedings took place exclusively before the PTO. Ex parte reexamination, created by the 1980 Bayh-Dole Act, allows anyone, including the patent owner, to request reexamination of a patent. [63] The request can be made at any time during the life of a patent, but the reexamination is limited to issues of obviousness and novelty on the basis of prior art consisting of patents or printed publications.[64] The party requesting the reexamination submits prior art to the PTO that it believes calls into question the obviousness or novelty of the patent. The PTO will grant the petition and order an ex parte reexamination if the petition raises a “substantial new question of patentability.”[65]

If the ex parte reexamination is granted, it involves only the patent owner and the PTO; any third-party petitioners are excluded from the process.[66] The reexamination advances much like the original examination of the patent application: none of the patent claims are presumed valid and the PTO uses the broadest reasonable construction to interpret the claims.[67] Because this broad construction standard is more likely to interpret claims as invalid, patent owners are allowed to amend their claims to narrow their scope and avoid invalidation of the patent.[68]

Ex parte reexamination has never gained popularity because, as critics claim, it does not allow any third-party participation beyond the initial reexamination request.[69] In response to concerns of its underutilization, Congress enacted an alternative reexamination procedure in 1999: inter partes reexamination.[70] Although similar to ex parte reexamination in almost every way, inter partes reexamination could not be initiated by the patent owner,[71] and it allowed substantial involvement of third parties in the reexamination process.[72] The two procedures existed side-by-side until inter partes reexamination was replaced by the new administrative procedure established by the AIA in 2012.

B. Inter Partes Review

The AIA, perhaps the most significant reform to the patent system in sixty years,[73] created several new procedures for reexamining the validity of patents.[74] A primary goal of the AIA was to provide a swifter resolution to patent reexaminations than the pre-AIA procedures.[75] Congress had grown increasingly concerned that reexaminations were “too lengthy and unwieldy to actually serve as an alternative to litigation when users are confronted with patents of dubious validity.”[76] The average length of an ex parte reexamination proceeding in 2012 was about 27.9 months,[77] and the average length of an inter partes reexamination was thirty-six months.[78] In contrast, the average length of patent litigation in the courts prior to the AIA was 27.36 months.[79] Thus, the existing reexamination procedures were unable to offer a quicker resolution to patent disputes than litigation. To remedy this, Congress intended the AIA “to establish a more efficient and streamlined patent system.” [80]

Congress also sought, with the AIA, to “improve patent quality and limit unnecessary and counterproductive litigation costs.”[81] On the one hand, Congress recognized the importance of challenging weak patents because “patents of dubious probity only invite legal challenges that divert money and other resources from more productive purposes, purposes such as raising venture capital, commercializing inventions and creating jobs.”[82] Yet it also accepted that provisions under the pre-AIA reexamination procedures had threatened strong patents by making the reexaminations “too easy to initiate and used to harass legitimate patent owners.”[83] Indeed, combating patent-assertion entities, pejoratively known as “patent trolls,” was cited as a primary goal of the AIA.[84] Thus, to balance the role of patent owners and challengers, Congress transformed post-issuance proceedings “from an examinational to an adjudicative proceeding.”[85] The new “mini-trials,” it was believed, would more fairly balance the role of patent holders and patent challengers in a manner similar to litigation.[86]

Two of the new administrative procedures created by the AIA—covered business method review and post-grant review—are not the focus of this Article. Covered business method review applies only to business method patents within financial services, making it largely irrelevant to the pharmaceutical industry. Post-grant review, which allows an invalidity challenge on any grounds during the first nine months of a patent,[87] applies only to patents issued under the AIA’s new first-inventor-to-file regime, and thus is still in its infancy.

The AIA proceeding currently garnering the most attention from the pharmaceutical industry is inter partes review (“IPR”). The AIA created IPR to replace inter partes reexamination—therefore, IPR resembles the earlier reexamination procedure in many respects.[88] Like inter partes reexamination, IPR challenges are available to anyone other than the patent owner,[89] and the validity of the patent can only be challenged for either obviousness or lack of novelty.[90] An IPR can be requested at any point during a patent’s lifetime, beginning nine months after the patent’s issuance.[91] However, an IPR may not be sought if the petitioner has previously filed a civil action challenging the validity of the same claim,[92] or has been sued for infringing the patent in question more than a year prior.[93]

However, IPR differs from the earlier inter partes reexamination in two important respects. First, unlike the paper administrative proceeding of inter partes reexamination, IPR is an adjudicative proceeding before the newly-created Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). The PTO will grant an IPR request (i.e. make an “institution” decision) and order a full trial before the PTAB if there is a “reasonable likelihood that the petitioner would prevail with respect to at least 1 of the claims challenged in the petition.”[94] A PTAB trial resembles a traditional trial, but with more limited discovery, depositions, and cross-examination.[95]

Second, IPR offers users a significantly speedier resolution than did inter partes reexamination. An inter partes reexamination often took years to reach a decision. In contrast, the PTAB must, by statute, make a final decision on an IPR claim within twelve to eighteen months.[96]

IPR is much more popular than the previous reexamination procedures. Between 2000 and its abolition in 2012, there were a total of 1,919 inter partes reexamination requests filed, or on average, 148 per year.[97] Between 2000 and 2014, there were a total of 7,709 ex parte reexamination requests filed, or on average, 514 per year.[98] Additionally, in the first nine months of fiscal 2016, 1,126 IPR petitions have already been filed.[99] By contrast, fiscal years 2014 and 2015 saw the filing of 1,310 and 1,737 IPR petitions, respectively.[100]

Moreover, IPR is significantly more friendly to patent challengers than the previous reexamination procedures. Of the completed trials that have reached a final written decision, the PTAB has invalidated at least some of the patent claims in a patent in 85% of cases and all of the patent claims in a patent in 70% of cases.[101] By contrast, from 1999 to its abolition in 2012, only 31% of inter partes reexaminations resulted in the cancellation of all claims of the challenged patents.[102] Similarly, from its advent in 1981 through 2014, only 12% of ex parte reexaminations have ended with the cancellation of all of the challenged patents’ claims.[103]

IV. IPR’s Pro-Challenger Bias

Congress designed the new IPR proceeding to improve patent quality by providing a more efficient pathway to challenge patents of dubious quality. The popularity of IPR compared to the pre-AIA reexamination procedures suggests that many challengers perceive significant advantages in the new proceedings. For many types of patents, an increase in post-issuance proceedings should produce clear social benefits: the more efficient resolution of patent disputes will allow more resources to be allocated to productive purposes. However, for pharmaceutical patents, IPR proceedings may instead create significant social costs. Unlike other industries, specific qualities of both the pharmaceutical industry and pharmaceutical patent litigation combine to create very different effects for the new IPR proceeding.

With the Hatch-Waxman Act and the BPCIA, Congress provided a litigation pathway for challenging pharmaceutical patents that balances the interests of brand patent holders with generic patent challengers. By all accounts, Hatch-Waxman has successfully achieved its goals of promoting brand innovation while facilitating generic entry. Generic drugs now account for 89% of drugs dispensed,[104] yet brand companies still invest significantly in R&D, accounting for over 90% of the spending on the clinical trials necessary to bring new drugs to market.[105] Although the BPCIA is still in its infancy, it was also explicitly designed to protect biologics’ patent terms while incentivizing biosimilar entry in the market.

Yet with IPR, Congress created an entirely new pathway for challenging pharmaceutical patents. As this section discusses, critical differences between district court litigation and IPR proceedings jeopardize the delicate balance Hatch-Waxman and the BPCIA sought to achieve between patent holders and patent challengers. As IPR has grown in popularity, it has become evident that these proceedings favor patent challengers. This change threatens to disrupt the nature of competition in the pharmaceutical industry, brand companies’ incentives to innovate, and consumers’ access to life-improving and life-saving drugs.

First, in IPR proceedings, the PTAB applies a lower standard of proof for invalidity than do district courts in either Hatch-Waxman or BPCIA proceedings. In district court, patents are presumed valid and challengers must prove each patent claim invalid by “clear and convincing evidence.”[106] In contrast, no such presumption of validity applies in IPR proceedings, and challengers must only prove patent claims invalid by the “preponderance of the evidence.”[107] This significantly reduced burden of proof gives patent challengers in PTAB cases an important advantage over district court litigation.

In addition to the lower burden, it is also easier to meet the standard of proof in the PTAB trial. One of the most contested parts of patent litigation is claim construction. Claim construction is the translation of the technical patent claims that define the scope of the patentee’s legal rights into understandable language.[108] District courts construe claims according to their “ordinary and customary meaning” to a person of ordinary skill in the art.[109] By contrast, the PTAB uses the more lenient “broadest reasonable interpretation” standard in IPR proceedings.[110] In many cases, these two standards will yield the same construction and conclusions on invalidity. In some cases the PTAB will interpret patent claims as “claiming too much” (using their broader standard), resulting in the invalidation of more patents.[111] Indeed, the Supreme Court recently recognized in Cuozzo that these different standards “may produce inconsistent results and cause added confusion”[112] and that “use of the broadest reasonable construction standard increases the possibility that the examiner will find the claim too broad (and deny it).”[113] Yet the Court concluded that, because the AIA did not specify which standard applies in PTAB trials, the decision of claim construction standard was left to the PTO.[114]

The use of the broadest reasonable construction is not new in the patent office. The PTO uses this standard during its initial examination of patent applications and during ex parte reexaminations.[115] In these proceedings, the justification for broadly interpreting claims is that patent owners will have an opportunity to amend their patents, so claims can be scrutinized using the broadest lens without necessarily resulting in patent invalidation.[116] However, patent owners are rarely allowed to amend claims in IPR proceedings even though the PTAB uses the broadest reasonable interpretation. Of the 118 completed trials in which the PTAB decided a motion to amend (which were requests to substitute patent claims) the board allowed the patent owner to amend claims in only six trials, or 5% of the total.[117] Thus, the PTAB’s use of the broadest reasonable construction standard in IPR proceedings will necessarily result in more patent invalidations than in either district court litigation or in ex parte reexaminations.

PTAB decisions in IPR proceedings are also given more deference than district court decisions. A district court decision upholding the validity of a patent does not prevent a later PTAB challenge by the same patent challenger within a year, essentially giving patent challengers “two bites at the apple.”[118] As long as an IPR petitioner meets the requirements—it has not been sued for infringing the patent in question more than a year prior,[119] and has not previously filed a civil action challenging the validity of the same claim[120]—a patent challenger that was unsuccessful in invalidating a patent in district court may pursue a subsequent IPR proceeding challenging the same patent.[121] And the PTAB’s subsequent decision to invalidate a patent can often “undo” a prior district court decision. In fact, a patent challenger who prevails in a subsequent IPR proceeding can avoid a prior district court judgment finding infringement and imposing damages or issuing an injunction.[122] Thus, pharmaceutical patent holders face persistent uncertainty about the validity of their patents.[123] Even if a patent is found valid in district court, and the validity is affirmed on appeal, the patent could later be found invalid in an IPR proceeding because the PTAB applies lower standards of proof and broader claim construction standards. The Federal Circuit could then affirm the PTAB’s decision, because with the different standards, the PTAB’s finding of invalidity is not necessarily in conflict with the district court’s finding of validity.

Similarly, although both district court judgments and PTAB decisions are appealable to the Federal Circuit,[124] the court applies a more deferential standard of review to PTAB decisions. Whereas a district court’s factual findings in a bench trial are reviewed for “clear error,”[125] the PTAB’s factual findings are reviewed using the more deferential “substantial evidence” standard.[126] The closer judicial review of district court factual findings means that these decisions are more likely to be overturned on appeal than are PTAB decisions. The more deferential review granted to the PTAB’s factual findings is especially troublesome given the more limited fact-finding in IPR proceedings. In contrast to the expansive discovery and witness testimony that is common in district court litigation, discovery is significantly restricted and live testimony is rarely allowed in IPR proceedings.[127] Thus, the Federal Circuit applies a more deferential review of factual findings that are based on less evidence. This approach is not only nonsensical, it will inevitably lead to more errors.

Another critical difference between district court litigation and IPR proceedings lies in the standing requirement. To challenge a patent in district court, a petitioner must have sufficient Article III standing, which the courts have generally interpreted to require that the petitioner has engaged in infringing activity and faces the threat of suit.[128] In contrast, IPR proceedings do not have a standing requirement, allowing any member of the public other than the patent owner to initiate an IPR challenge.[129] As a result, approximately 30% of IPR challengers have not been defendants in district court litigation, and thus would likely not have had Article III standing.[130]

Legal commentators, including advocates of administrative proceedings, have recognized that the lack of a standing requirement in IPR proceedings could lead to harassment suits brought by competitors intending only to impose costs on the other party.[131] Indeed, the lack of a standing requirement has given rise to “reverse patent trolling,” in which entities that are not litigation targets, or even participants in the same industry, offensively use IPR or the threat of IPR to profit. Under this opportunistic practice, reverse trolls threaten to file an IPR petition challenging the validity of a patent unless the patent holder agrees to specific pre-filing settlement demands. These demands are arguably extortion,[132] but with the high rate of decisions to institute IPRs and the high rate of patent invalidations in IPR proceedings, companies take a big risk if they do not agree to such demands.[133]

Moreover, pharmaceutical patents face the threat of another, distinct form of abuse under IPR—the novel hedge fund practice of short selling a brand drug company’s stock, then filing an IPR challenge in hopes of crashing the stock and profiting from the short sale.[134] Pharmaceutical patents are especially vulnerable to this abuse because the stock value of a small or mid-size pharmaceutical company typically depends critically on the success of an individual drug, which in turn typically depends on an individual patent. Thus, while hypothetically invalidating a patent owned by Apple or Samsung may do little to affect the companies’ stock price because of the variety of product offerings and multitude of patents underlying their technology, invalidating a pharmaceutical patent could cause a pharmaceutical company’s stock to plummet. Indeed, the data on IPR petitioners suggest that pharmaceutical patents are especially vulnerable to this sort of abuse; whereas in most industries, over 70% of IPR challengers were defendants in district court litigation (granting them Article III standing), for the drug industry, this figure is less than 50%.[135] And while critics have argued that the hedge fund strategy amounts to illegal market manipulation,[136] the PTAB has thus far allowed the practice, concluding that “profit is at the heart of nearly every patent and nearly every inter partes review,”[137] and “Congress did not limit inter partes reviews to parties having a specific competitive interest in the technology covered by the patents.”[138]

The differences between district court litigation and IPR proceedings are creating a significant deviation in patent invalidation rates under the each pathway. From 1996 to 2015, patents were invalidated in 34% to 39% of district court cases.[139] Additionally, of the 1,046 PTAB trials in IPR proceedings that were completed by June, 2016, a shocking 70% resulted in the invalidation of all claims of the challenged patents.[140] This higher invalidation rate in IPR proceedings is especially meaningful because, while a challenged patent can only be invalidated in an IPR for lack of novelty or for obviousness, a challenged patent in district court can also be invalidated on other grounds.[141]

To date, IPR petitions filed on pharmaceutical patents have made up only a small percentage of the total petitions. Of the 4,253 IPR petitions filed as of March 2016, only 228, or 5.36% were filed on patented pharmaceuticals.[142] Yet the number of IPR challenges to pharmaceutical patents continues to increase; twice as many IPR petitions were filed on pharmaceutical patents in 2015 compared to 2014, and the number is on pace to increase again in 2016.[143]

Although only a handful of these pharmaceutical IPR petitions have reached a written decision in a PTAB trial, it appears that, similar to other industries, brand patent holders are faring worse in IPR proceedings. The PTAB has invalidated approximately 50% of the total claims considered in written decisions.[144] However, of the 220 Hatch-Waxman cases litigated to trial or summary judgment from 2000 to 2012, only 21% resulted in invalidation of the patents.[145]

V. Correcting the Imbalance

The growing popularity of IPR threatens to dislodge the delicate balance that Hatch-Waxman and the BPCIA sought to strike between brand patent holders and generic patent challengers. To achieve this balance, Hatch-Waxman’s litigation pathway includes several protections for patent holders. In contrast, IPR proceedings clearly tilt the balance in the patent challenger’s favor. Although IPR challenges to pharmaceutical patents do not yet occur in large numbers, their popularity is increasing swiftly. Moreover, even the risk of facing a pro-challenger IPR is enough to create significant uncertainty for brand drug companies. IPR makes intellectual property rights less certain: patents are more likely to be invalidated than they are in district court and even a favorable district court ruling doesn’t guarantee that a patent won’t be invalidated by a subsequent IPR.

Uncertain patent rights will, in turn, lead to less innovation in the pharmaceutical industry. Brand drug companies are largely responsible for pharmaceutical innovation; since 2000, they have spent over half a trillion dollars on R&D, and they currently account for over 90% of the spending on the clinical trials necessary to bring new drugs to market.[146] But if brand companies can’t rely on their patents, they will have less incentive to engage in costly R&D. Companies will not spend the billions of dollars it typically costs to bring a new drug to market when they can’t be certain if the patents for that drug can withstand IPR proceedings that are clearly stacked against them.[147] Indeed, a substantial body of literature shows that strong, predictable patent rights are critical for innovation.[148] If IPR increases the uncertainty of pharmaceutical patent rights, innovation will suffer, harming consumers’ health outcomes.[149]

Although proponents of IPR claim that Hatch-Waxman “has been so thoroughly gamed” that it no longer promotes generic entry in the market,[150] the evidence does not support this assertion. Generic drugs now account for 89% of drugs dispensed,[151] and within twelve months of generic entry, these drugs regularly capture over 80% of brand drugs’ market share.[152] Moreover, generic utilization continues to grow; these drugs will soon account for over 90% of drugs dispensed in this country. While strategies adopted by certain pharmaceutical companies have been an attempt to avoid generics’ continued erosion of brand market share, the courts have typically addressed any practices found to be anticompetitive.[153] Certainly closing any occasional perceived loophole is smarter than providing an end run around Hatch-Waxman and creating an entirely new to pathway to challenge patents.

Instead, Congress should align certain provisions in IPR to mirror those in Hatch-Waxman. First, Congress should ensure that IPR patent claims are interpreted using the same claim construction standard as courts use in Hatch-Waxman litigation. Currently, district courts construe claims according to their “ordinary and customary meaning” to a person of ordinary skill in the art,[154] but the PTAB uses the more lenient “broadest reasonable interpretation” standard in IPR proceedings.[155] Changing the IPR claim construction standard to match that of the courts will ensure that the PTAB is not invalidating too many patents, particularly when patent owners cannot easily amend their claims. Alternatively, if the claim construction standards in IPR and Hatch-Waxman litigation are not aligned, the right to amend in IPR proceedings should be expanded. Then, the justification for using the “broadest reasonable interpretation” in IPR would correspond to the justification for using this standard in initial patent examinations and ex parte reexaminations: because patent owners will have an opportunity to amend their patents, claims can be scrutinized using the broadest lens without necessarily resulting in patent invalidation.

Indeed, the Supreme Court recently recognized in Cuozzo that these different standards “may produce inconsistent results and cause added confusion,”[156] and that “use of the broadest reasonable construction standard increases the possibility that the examiner will find the claim too broad (and deny it).”[157] However, the court concluded that only Congress was in a position to mandate a different statute:

We interpret Congress’ grant of rulemaking authority in light of our decision in Chevron . . . [w]here a statute is clear, the agency must follow the statute . . . But where a statute leaves a “gap” or is “ambigu[ous],” we typically interpret it as granting the agency leeway to enact rules that are reasonable in light of the text, nature, and purpose of the statute . . . The statute contains such a gap: No statutory provision unambiguously directs the agency to use one standard or the other.[158]

Second, Congress should provide that standards of review in the Federal Circuit are the same for PTAB decisions and district court decisions. Currently a district court’s factual findings are reviewed for “clear error,”[159] but the PTAB’s factual findings are reviewed using the more deferential “substantial evidence” standard.[160] The inconsistency is especially troublesome given that PTAB factual findings are based on less evidence than are court factual findings. Aligning the standards of review will ensure that, at least at the appellate level, court decisions and PTAB decisions will be reviewed with equal deference.

Indeed, courts have recognized the problems with the inconsistent standards. In April, 2016, the Federal Circuit denied an en banc review on whether the clear error standard should be applied in appeals from IPR proceedings.[161] The Court concluded that the “application of the substantial evidence standard of review is seemingly inconsistent with the purpose and content of the AIA,”[162] yet the Court was not the correct venue to change the standard: “Because Congress failed to expressly change the standard of review employed by this court in reviewing Board decisions when it created IPR proceedings via the AIA, we are not free to do so now.”[163] Instead, the Court called on Congress to align the standards of review: “a substantial evidence standard of review makes little sense in the context of an appeal from an IPR proceeding. But the question is one for Congress.”[164]

Third, Congress could eliminate certain abuses of IPR by adding a standing requirement that mirrors Article III standing. Currently, any member of the public other than the patent owner can initiate an IPR challenge.[165] The lack of a standing requirement has allowed reverse patent trolls and hedge funds to exploit IPR proceedings for profit. And although the pharmaceutical industry is fighting the abuses of reverse trolls,[166] and IPR challenges by hedge funds may ultimately prove to be an ineffective strategy,[167] even the risk of such predatory challenges create uncertainty for patent owners.

Congress currently has bills pending before it that would limit standing to exclude parties wielding the IPR for either extortionary purposes or for non-patent related consequences, such as affecting a company’s stock value. [168] Adding such a standing requirement would prevent abuse of the IPR proceedings by parties that do not have a direct interest in the validity of a patent.

Alternatively, Congress could conclude that amending the AIA to align all IPR proceedings with Hatch-Waxman litigation is overkill because the current inconsistencies are only relevant and meaningful to pharmaceutical patents. In this case, Congress could instead exempt biopharmaceutical patents from the AIA, excusing patents already subject to Hatch-Waxman or the BPCIA from the IPR process entirely.[169] There is certainly a precedent for such reform—Congress has treated pharmaceutical patents differently from other types of patents since at least 1984. A carve-out would preserve the efficiency benefits of IPR for all non-pharmaceutical patents while restoring the balance that was established by Hatch-Waxman over three decades ago and is critical to pharmaceutical innovation.

Conclusion

For patents in most industries, IPR offers a new, efficient alternative to challenge patents of dubious quality. However, for pharmaceutical patents, IPR is a means to avoid the litigation pathway created under Hatch-Waxman over thirty years ago. Critical differences between district court litigation in Hatch-Waxman proceedings and IPR jeopardize the delicate balance Hatch-Waxman sought to achieve between patent holders and patent challengers. As IPR has grown in popularity, it has become evident that these proceedings favor patent challengers; compared to district court challenges, patents are found invalid in almost twice as many IPR challenges.

In recent decisions, courts have recognized the anti-patentee bias of IPR, yet punted to Congress the job of changing the provisions. It is critical that Congress reduce the disparities between IPR proceedings and Hatch-Waxman litigation. The high patent invalidation rate in IPR proceedings creates significant uncertainty in intellectual property rights. Uncertain patent rights will, in turn, disrupt the nature of competition in the pharmaceutical industry, drug innovation, and consumers’ access to life-improving drugs.

[1] Leahy-Smith America Invents Act, Pub. L. No. 112-29, 125 Stat. 284 (2011).

[2] Cf. PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2016 Patent Litigation Study: Are We at An Inflection Point? 9 fig.11 (2016), https://www.pwc.com/us/en/forensic-services/publications/assets/2016-pwc-patent-litigation-study.pdf.

[3] U.S. Pat. & Trademark Off., Patent Trial and Appeal Board Update 10 (2016), https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2016-6-30%20PTAB.pdf.

[5] See Cuozzo Speed Tech. LLC v. Lee (Cuozzo), 136 S. Ct. 2131, 2145 (2016).

[6] Id. at 2144.

[8] Id. at 2 (majority opinion).

[9] See Coal. for Affordable Drugs VI LLC v. Celgene Corp. (Celgene), Nos. IPR2015-01092, IPR2015-01096, IPR2015-01102, IPR2015-01103 and IPR2015-01169, at 3 (P.T.A.B. Sept. 25, 2015). Though they may be excluded from appellate review under Article III.

[10] See IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics, Medicine Use and Spending in the U.S., A Review of 2015 and Outlook to 2020, 46 (2016), http://www.imshealth.com/en/thought-leadership/medicines-use-and-spending-in-the-us-a-review-of-2015-and-outlook-to-2020#form.

[11] See PhRMA, 2016 Profile Biopharmaceutical Research Industry 1, 35 (2016), http://phrma.org/sites/default/files/pdf/biopharmaceutical-industry-profile.pdf.

[12] See U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off. GAO-12-371R, Drug Pricing: Research on Savings from Generic Drug Use 2 (2012), http://www.gao.gov/assets/590/588064.pdf; see also IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics, supra note 10, at 46; PhRMA, Chartpack: Biopharmaceuticals in Perspective 56 (2015), http://www.phrma.org/sites/default/files/pdf/chartpack-2015.pdf.

[13] See IMS Institute for Healthcare Information, Price Declines After Branded Medicines Lose Exclusivity in the U.S. 3 (2016), http://www.imshealth.com/files/web/IMSH%20Institute/Healthcare%20Briefs/Price_Declines_after_Branded_Medicines_Lose_Exclusivity.pdf.

[14] See Office of the Assistant Sec’y for Planning & Evaluation, U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Expanding the Use of Generic Drugs (Dec. 1, 2010), http://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/expanding-use-generic-drugs#11; see also Henry Grabowski, Patents and New Product Development in the Pharmaceutical and Biotechnology Industries, 8 Geo. Pub. Pol’y Rev. 7, 13 (2003) (“Generic firms can file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), a process that takes only a few years and typically costs a few million dollars.”).

[15] Brand companies spent between $103 million and $249 million on the top-ten most heavily advertised drugs in 2014 alone. See Beth Snyder Bulik, The Top-10 Most Advertised Prescription Drug Brands, FiercePharma, http://www.fiercepharmamarketing.com/special-reports/top-10-most-advertised-prescription-drug-brands (last visited Nov. 1, 2016).

[16] See Henry Grabowski, Genia Long & Richard Mortimer, Recent Trends in Brand‐Name and Generic Drug Competition, 17 J. Med Econ. 207, 211-12 (2014).

[17] See U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., supra note 12, at 2; see also Generic Pharmaceutical Association, Generic Drug Savings in the U.S. (2015), http://www.gphaonline.org/media/wysiwyg/PDF/GPhA_Savings_Report_2015.pdf.

[18] See U.S. Cong. Budget Off., How Increased Competition from Generic Drugs Has Affected Prices and Returns in the Pharmaceutical Industry 38 (1998), https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/105th-congress-1997-1998/reports/pharm.pdf.

[20] Id. at 43.

[21] See PricewaterhouseCoopers, From Vision to Decision Pharma 2020, at 6 (2012), http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/pharma-life-sciences/pharma2020/assets/pwc-pharma-success-strategies.pdf.

[22] See John A. Vernon, Joseph Golec & Joseph A. DiMasi, Drug Development Costs When Financial Risk is Measured Using the Fama‐French Three‐Factor Model, 19 Health Econ. 1002, 1004 (2010).

[23] See, e.g., Kenneth Kaitin, Natalie Bryant & Louis Lasagna, The Role of the Research-Based Pharmaceutical Industry in Medical Progress in the United States, 33 J. of Clinical Pharmacology 412, 414 (1993) (92% of new drugs are discovered by private branded companies).

[25] Id. at 35.

[26] Id. at 20.

[27] Id. at 47.

[28] See Mark Duggan & Scott Morton, The Distortionary Effects of Government Procurement: Evidence from Medicaid Prescription Drug Purchasing, 121 Q. J. Econ. 1, 5 (2006); see also Amy Finkelstein, Static and Dynamic Effects of Health Policy: Evidence from the Vaccine Industry, 119 Q. J. Econ. 527, 540 (2004); Daron Acemoglu & Joshua Linn, Market Size in Innovation: Theory and Evidence from the Pharmaceutical Industry, 119 Q. J. Econ. 1049, 1053 (2004).

[29] See Joseph Golec, Shantaram Hegde & John A. Vernon, Pharmaceutical R&D Spending and Threats of Price Regulation, 45 J. of Financial & Quantitative Analysis 239, 240-41 (2010); see also Frank R. Lichtenberg, Public Policy and Innovation in the U.S. Pharmaceutical Industry, in Public Pol’y and the Econ. of Entrepreneurship (Douglas Holtz-Eakin & Harvey S. Rosen eds., 2004).

[30] See Frank R. Lichtenberg, Pharmaceutical Innovation, Mortality Reduction, and Economic Growth 1 (Columbia U. & Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Res., Conf. Presentation on The Econ. Value of Med. Res., Working Paper No. 6569, 1998), http://www.nber.org/papers/w6569.

[31] See Craig Garthwaite, The Economic Benefits of Pharmaceutical Innovations: The Case of Cox-2 Inhibitors, 4 Applied Econ. 116, 118 (2012).

[32] See Frank R. Lichtenberg, Benefits and Costs of Newer Drugs: An Update, 28 Managerial & Decision Econ. 485, 485 (2007).

[33] Hatch-Waxman Act, Pub. L. No. 98-417, 98 Stat. 1585. (1984).

[34] See Margo Bagley, Patent Term Restoration and Non-Patent Exclusivity in the U.S., in Pharmaceutical Innovation, Competition, and Pat. L. 111, 114-15 (Josef Drexel & Nari Lee eds., 2013).

[35] 21 U.S.C. § 355(c)(3)(E)(ii) (2012).

[36] Id.

[37] 21 U.S.C. § 355(j) (2012).

[38] See Office of the Assistant Sec’y for Planning & Evaluation, supra note 14; see also Henry Grabowski, supra note 14.

[39] 35 U.S.C. § 271(e).

[40] See, e.g., U.S. Dep’t Health & Hum. Servs., Guidance for Industry: 180-Day Generic Drug Exclusivity Under the Hatch-Waxman Amendments to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (1998), http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/…/Guidances/ucm079342.pdf.

[42] Id.

[45] 42 U.S.C. § 262(i)(2)(B) (2012).

[46] See Jason Kanter & Robin Feldman, Understanding & Incentivizing Biosimilars, 58 Hastings L.J. 57, 59 (2012) (citing 42 U.S.C. § 262(i)(I) (2006)).

[47] See, e.g., Joan Kerber-Walker, Small Molecules, Large Biologics, and the Biosimilar Debate, Ariz. Bioindustry Assoc. (Feb. 18, 2013), http://www.azbio.org/small-molecules-large-biologics-and-the-biosimilar-debate.

[48] See Anthony D. So & Samuel L. Katz, Biologics Boondoggle, N.Y. Times (Mar. 7, 2010), http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/08/opinion/08so.html?_r=0.

[49] See 42 U.S.C. § 262(i)(2)(B) (2012); see also Zachary Brennan, FDA Likely to Require Substantial Clinical Data for Interchangeable Biosimilars, Lawyers Say (Jan. 12, 2016), http://www.raps.org/Regulatory-Focus/News/2016/01/12/23887/FDA-Likely-to-Require-Substantial-Clinical-Data-for-Interchangeable-Biosimilars-Lawyers-Say/ (noting that the FDA is still determining what pre-clinical and clinical data will be required for approval).

[50] 42 U.S.C. § 262(i)(3) (2012).

[52] 42 U.S.C. § 262(k)(7)(A); see, e.g., Elizabeth Richardson et al., Biosimilars, Health Aff. (Oct. 10, 2013), http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=100.

[53] 42 U.S.C. § 262(k)(7)(B) (2012).

[55] See Lang v. Pacific Marine & Supply Co., 895 F.2d 761 (Fed. Cir. 1990) (noting that in other industries, it is possible to seek a declaratory judgment prior to the good entering the market); see also 35 U.S.C. § 271(a) (noting that it is also an infringement to merely offer to sell the invention even if the sale is not completed). Compare 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(2) (“It shall be an act of infringement to submit—(A) an application under section 505(j) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act . . . for a drug claimed in a patent or the use of which is claimed in a patent . . . .”), with 35 U.S.C. § 271(a) (“[W]hoever without authority makes, uses, offers to sell, or sells any patented invention, within the United States . . . during the term of the patent therefor, infringes the patent.”).

[56] See, e.g., Jacob Sherkow, Litigating Patented Medicines: Courts and the PTO 8 (2015), http://law.stanford.edu/wpcontent/uploads/sites/default/files/event/862753/media/slspublic/Litigating%20Patented%20Medicines%20-%20Courts%20and%20the%20PTO.pdf; Louis Fogel & Peter Hanna, The Biosimilar Regulatory Pathway and the Patent Dance 1-2 (2014), https://jenner.com/system/assets/publications/13837/original/The_Biosimilar_Regulatory_Pathway_and_the_Patent_Dance.pdf?1420753075.

[57] Amgen Inc. v. Sandoz Inc., 794 F.3d 1347, 1360 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (holding that notice of commercial marketing is only effective after FDA approval of the biosimilar application and that the information exchange process is optional).

[58] See 42 U.S.C. § 262(k)(6) (2012) (noting that exclusivity extends until the earliest of: (i) one year after the first commercial marketing of the first-approved interchangeable biosimilar; (ii) eighteen months after a final court decision or the dismissal of a suit against the first interchangeable biosimilar; (iii) forty-two months after the approval of the first interchangeable biologic if patent litigation is still ongoing; or (iv) eighteen months after the approval of the first interchangeable biosimilar if the applicant has not been sued).

[59] See, e.g., Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303, 1312-18 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (en banc).

[60] See, e.g., Wayne B. Paugh, The Betrayal of Patent Reexamination: An Alternative to Litigation, Not a Supplement, 19 Fed. Cir. B.J. 177, 181-88 (2009).

[61] See Patlex Corp. v. Mossinghoff, 758 F.2d 594, 602 (Fed. Cir.), aff’d in part, rev’d on other grounds, 771 F.2d 480 (1985); H.R. Rep. No. 107-120, at 3 (2001) (“The 1980 reexamination statute was enacted with the intent of achieving three principal benefits. It is noted that the reexamination of patents by the PTO would: (i) settle validity disputes more quickly and less expensively than litigation; (ii) allow courts to refer patent validity questions to an agency with expertise in both the patent law and technology; and (iii) reinforce investor confidence in the certainty of patent rights by affording an opportunity to review patents of doubtful validity.”).

[62] H.R. Rep. No. 96-1307, pt. 1, at 3-4 (1980), as reprinted in 1980 U.S.C.C.A.N. 6460, 6463.

[63] See, e.g., Bayh-Dole Act, Pub. L. No. 96-517, ch. 30, § 302, 94 Stat. 3015, 3015 (1980) (codified at 35 U.S.C. § 302 (2012)) (“Any person at any time may file a re-quest for reexamination by the Office of any claim of a patent on the basis of any prior art cited . . . .”).

[64] 37 C.F.R. § 1.552 (2014); U.S. Pat. & Trademark Off., MPEP § 2258 (9th ed. Rev. Mar. 2014) [hereinafter MPEP].

[65] 35 U.S.C. § 303(a) (2012).

[66] 37 C.F.R. § 1.550(g) (2014) (“The active participation of the ex parte reexamination re-quester ends with the [grant of the petition for reexamination], and no further submissions on behalf of the reexamination requester will be acknowledged or considered.”).

[67] MPEP § 2111 (“During patent examination, the pending claims must be ‘given their broadest reasonable interpretation consistent with the specification.’”).

[68] Douglas Duff, Comment, The Reexamination Power of Patent Infringers and the Forgotten Inventor, 41 Cap. U. L. Rev. 693, 710 (2013) (“[R]eexamination affords the patent owner a chance to narrow the scope of the claims to avoid being invalidated based on subsequently discovered prior art.”).

[69] Shannon M. Casey, The Patent Reexamination Reform Act of 1994: A New Era of Third Party Participation, 2 J. Intell. Prop. L. 559 (1995); Marvin Motsenbocker, Proposal to Change the Patent Reexamination Statute to Eliminate Unnecessary Litigation, 27 J. Marshall L. Rev. 887, 898 (1994); Gregor N. Neff, Patent Reexamination—Valuable, But Flawed: Recommendations for Change, 68 J. Pat. & Trademark Off. Soc’y 575 (1986).

[70] American Inventors Protection Act of 1999, Pub. L. No. 106-113, 113 Stat. 1501 (codified in relevant part in 35 U.S.C. §§ 311-318 (2006)) (repealed 2012).

[71] Patent owners cannot request inter partes reexaminations of their patents because there would be no third party to participate. See 35 U.S.C. § 311(a) (2012).

[72] 35 U.S.C. §§ 311-318 (2012).

[73] Andrei Iancu & Ben Haber, Post-Issuance Proceedings in the America Invents Act, 93 J. Pat. & Trademark Off. Soc’y 476, 476 (2011).

[74] Leahy-Smith America Invents Act, Pub. L. No. 112-29, 125 Stat. at 299-305 (2011)(setting forth procedures for IPR).

[75] See generally Joe Matal, A Guide to the Legislative History of the America Invents Act: Part II of II, 21 Fed. Cir. Bar J. 539, 599-604 (2012) (summarizing legislative history); H.R. Rep. No. 112-98, at 45 (2011).

[76] Sen. Patrick Leahy, Senate Begins Debate on Leahy-Smith America Invents Act, Press Release (Sept. 6, 2011), http://www.leahy.senate.gov/press/senate-begins-debate-on-leahy-smith-america-invents-act.

[77] U.S. Pat. & Trademark Off., Ex Parte Reexamination Filing Data, at 1 (Sept. 30, 2012), http://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ex_parte_historical_stats_roll_up_EOY2014.pdf.

[78] See PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2011 Patent Litigation Study: Patent Litigation Trends as the ‘America Invents Act’ Becomes Law 28 (2011) https://www.pwc.com/us/en/forensic-services/publications/assets/2011-patent-litigation-study.pdf.

[79] Id. at 28 (reporting the average time to trial as 2.28 years, or 27.36 months).

[80] H.R. Rep. No. 112-98, at 40 (2011).

[81] Id.

[82] Patent Quality Improvement: Post-Grant Opposition: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on Courts, The Internet & Intellectual Prop. of the H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 108th Cong. 1 (2004) (statement of Rep. Lamar Smith, Chairman, Subcomm. on Courts, the Internet & Intellectual Prop.).

[83] Sen. Patrick Leahy, supra note 74; see also 57 Cong. Rec. S5428 (daily ed. Sept. 8, 2011) (statement of Sen. Patrick Leahy) (asserting that the AIA post-issuance review proceedings provide more protections to patent holders against frivolous requests and harassment).

[84] See, e.g., 157 Cong. Rec. H4485-86 (daily ed. June 23, 2011) (statement of Rep. Lamar Smith) (explaining Congress’s thoughts regarding the predatory behavior of patent trolls).

[85] H.R. Rep. No. 112-98, at 46 (2011).

[86] Mark Consilvio & Jonathan Stroud, Unravelling the USPTO’s Tangled Web: An Empirical Analysis of the Complex World of Post-Issuance Patent Proceedings, 21 J. of Intell. Prop. L. 1, 12 (2014).

[87] 35 U.S.C. § 321 (2012).

[88] Id. §§ 311-319.

[89] Id. § 311(a).

[90] Id. § 311(b).

[91] Id. § 311(c)(1). An IPR request cannot be filed until the post-grant review window has expired. Id. § 311(c)(2).

[92] 35 U.S.C. § 315(a)(1) (2012).

[93] Id. § 315(b).

[94] Id. § 314(a).

[95] Id. § 326(a)(5); 37 C.F.R. § 42.51-42.53 (2012).

[96] 35 U.S.C. § 316(a)(11) (2012).

[98] Id. at 1.

[100] Id.

[101] Id. at 10. Specifically, out of the 1046 completed trials (as of June 30, 2016, 896 (85.66%) have invalidated at least one claim, and 736 (70.36%) have resulted in all claims being invalidated. Id.

[103] Id. at 2.

[106] Microsoft Corp. v. i4i Ltd., 131 S. Ct. 2238, 2242 (2011) (holding that a clear and convincing showing of invalidity is required to invalidate patents).

[107] 35 U.S.C. § 316(e) (2012) (establishing a “preponderance of the evidence” standard in IPR proceedings).

[108] See generally Dennis Crouch, Claim Construction: A Structured Framework, PatentlyO (Sept. 29, 2009), http://patentlyo.com/patent/2009/09/claim-construction-a-structured-framework-1.html.

[109] See, e.g., Phillips, 415 F.3d at 1312-13.

[110] 37 C.F.R. § 42.100(b) (2012).

[111] See, e.g., PPC Broadband, Inc. v. Corning Optical Communications RF, LLC, 815 F.3d 734 (2016) (“This case hinges on the claim construction standard applied—a scenario likely to arise with frequency. And in this case, the claim construction standard is outcome determinative.”).

[112] Cuozzo, 136 S. Ct. 2131, at 2146.

[113] Id. at 2145.

[114] Id. at 2136.

[115] See, e.g., Phillips, 415 F.3d at 1316 (“The Patent and Trademark Office (“PTO”) determines the scope of claims in patent applications not solely on the basis of the claim language, but upon giving claims their broadest reasonable construction. . . .”); In re Yamamoto, 740 F.2d 1569, 1571 (Fed. Cir. 1984) (stating that claims subject to reexamination will “be given their broadest reasonable interpretation consistent with the specification, and limitations appearing in the specification”).

[116] MPEP § 2111 (“Because applicant has the opportunity to amend the claims during prosecution, giving a claim its broadest reasonable interpretation will reduce the possibility that the claim, once issued, will be interpreted more broadly than is justified.”).

[117] U.S. Pat. & Trademark Off., Patent Trial and Appeal Board Motion to Amend Study: 4/30/2016, at 4 (2016), http://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2016-04-30%20PTAB%20MTA%20study.pdf. But see the Federal Circuit order in In re: Aqua Products, Inc., No. 2015-1177 (Aug. 12, 2016), in which the full court granted en banc review of the petitioner’s argument that the PTAB has “unduly restricted” the ability to amend patent claims.

[118] The PTAB justifies this second bite by maintaining that the petitioner is not a party to district court proceedings and that the two venues possess different burdens of proof. See, e.g., Amkor Tech., Inc. v. Tessera, Inc., IPR2013-00242, Paper 37 at 12 (P.T.A.B. Oct. 11, 2013).

[119] 335 U.S.C. § 315(b) (2012).

[120] 35 U.S.C. § 315(a)(1) (2012). Importantly, a counterclaim challenging the validity of a patent claim in an infringement action is not considered a civil action. 35 U.S.C. § 315(a)(1), (3) (2012).

[121] 35 U.S.C. §§ 315, 325 (2012).

[122] See generally Jay Chiu et. al, Pharmaceuticals at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, 30-32 (2015), http://www.goodwinlaw.com/news/2015/07/07_29_15-goodwin-procter-publishes-guidebook-on-litigating-pharmaceutical-cases?device=print; EPlus, Inc. v. Lawson Software, 789 F.3d 1349 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (vacating the injunction issued by the district court after a subsequent PTAB decision invalidated the patent); Fresenius USA, Inc. v. Baxter Int’l, Inc., 721 F.3d 1330, 1335, 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2013) (absolving the patent challenger of the damage award imposed by the district court after the USPTO subsequently cancelled the patent on reexamination).

[123] Some IPRs and district court litigation will naturally happen in tandem because IPRs will only consider invalidity determinations, while ANDA litigation also deals with infringement determinations. Generic companies may prefer to pursue a non-infringement determination in district court because, in contrast to a finding of invalidity, a finding of non-infringement keeps the patent in place so that competing generics will also have to show that they don’t infringe or that the patent is invalid or unenforceable. Moreover, non-infringement determinations will often be cheaper to litigate. In a non-infringement determination, the generic company has all of the information about its product, so the costs of evaluating non-infringement should be lower. In contrast, an invalidity determination requires a prior art search and analysis as to whether the claimed invention is novel, non-obvious and useful.

[124] 35 U.S.C. § 141 (2012).

[125] Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a)(6); United States v. Cazares, 121 F.3d 1241, 1245 (9th Cir. 1997). Findings in a jury trial in district court are reviewed using the “substantial evidence” standard. However, review of claim construction will always be different between appeals from district court proceedings and PTAB trials because claim construction at the district court is always decided by the judge, and thus, reviewed for clear error.

[126] 5 U.S.C. § 706(e) (2012); Merck, 820 F.3d at 433.

[127] See 37 C.F.R. §§ 42.51-42.53 (2015).

[128] See, e.g., MedImmune, Inc. v. Genentech, Inc., 549 U.S. 118, 127 (2007) (quoting Md. Cas. Co. v. Pac. Coal & Oil Co., 312 U.S. 270, 273 (1941)).

[129] See 35 U.S.C. § 311(a) (2012). Yet, a challenger who loses at the PTAB may have to meet Article III standing requirements in order to appeal. Cf. Consumer Watchdog v. Wis. Alumni Research Found., 753 F.3d 1258, 1261 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

[130] See Saurabh Vishnubhakat, Arti K. Rai, & Jay P. Kesan, Strategic Decision Making in Dual PTAB and District Court Proceedings, 31 Berkeley Tech. L.J. 45, 76 (2016).

[131] Jonathan Masur, Patent Inflation, 121 Yale L.J. 470, 522 (2011) (“[IPR] could potentially be abused by parties interested only in delaying and harassing competitors.”).

[132] See, e.g., Joseph Herndon, IPRs Threatened/Filed as Money-Making Strategy, Patent Docs (Aug. 16, 2016), http://www.patentdocs.org/2016/08/iprs-threatenedfiled-as-money-making-strategy.html; First Amended Complaint at 4, Chinook Licensing DE, LLC, v. RozMed LLC, C.A., No. 14-598-LPS (D. Del. June 13, 2014), ECF No. 9; Allergan Inc. v. Ferrum Ferro Capital LLC, No. SACV 15-00992 JAK (PLAx) (C.D. Cal. Jan. 20, 2016).

[134] See Joseph Walker and Rob Copeland, New Hedge Fund Strategy: Dispute the Patent, Short the Stock, Wall Street Journal (Apr. 7, 2015), http://www.wsj.com/articles/hedge-fund-manager-kyle-bass-challenges-jazz-pharmaceuticals-patent-1428417408.

[136] Kevin Penton, Biogen Wants Kyle Bass to Give up Financial Docs at PTAB, Law360 (July 9, 2015), http://www.law360.com/articles/677449/biogen-wants-kyle-bass-to-give-up-financial-docs-at-ptab; see also 162 Cong. Rec. H4361 (daily ed. July 6, 2016) (statement of Rep. Duffy) (expressing concern about a “potential[ly]” “deceptive and manipulative practice by some hedge funds to challenge the legitimacy of a drug patent while simultaneously shorting the drug manufacturer’s stock. These particular hedge funds game the system” by “publiciz[ing] numerous patent challenges,” “provok[ing] fear in the marketplace” and “driv[ing] down [the stock] prices” of these smaller companies.).

[137] Celgene, Nos. IPR2015-01092, IPR2015-01096, IPR2015-01102, IPR2015-01103 and IPR2015-01169, at 3.

[138] Id. at 4.

[139] PricewaterhouseCoopers, supra note 2, at 9 fig.11. Earlier studies found invalidation rates in district courts were around 46%. See John R. Allison & Mark A. Lemley, Empirical Evidence on the Validity of Litigated Patents, 26 AIPLA Q. J. 185, 205-06 (1998); Donald R. Dunner, Introduction, 13 AIPLA Q. J. 185, 186-87 (1985); Mark A. Lemley, An Empirical Study of the Twenty-Year Patent Term, 22 AIPLA Q. J. 369, 420 (1994) (finding that 56% of litigated patents to be valid between 1989 and 1994).