Joshua L. Simmons*

A pdf version of this article may be downloaded here.

Introduction

Despite the persistent notion that modern invention is performed by individual inventors in their garages, few would disagree that today most patentable inventive activity occurs in corporate and university settings and that most individuals who would be labeled “inventors” in the twenty-first century are employees of corporate entities.[1] In the corporate setting, if an employee creates a copyrightable work within the scope of his or her employment, the Copyright Act not only grants ownership of the work to the employer but actually considers the employer the “author” of the work.[2] By contrast, under the Patent Act, one who creates an invention is its inventor, and ownership will only pass to another, including an employer, through a written assignment.[3] In other words, unless there is an agreement to the contrary, an employer does not have any rights in an invention “which is the original conception of the employee alone.”[4]

Given the close relationship between copyright law and patent law,[5] it is puzzling that employees’ works and inventions would be treated so differently under the two disciplines. Yet, when one considers their historical foundation, it becomes clear that there were pivotal differences between the needs of the two disciplines in the nineteenth century that led to their modern formulations.[6] In particular, whereas the type of copyrightable works created in the nineteenth century transitioned from individual labors to collaborative labors among multiple individuals working together, which necessitated the collecting of rights in order to make use of the resulting copyrightable work, patentable inventions continued to be perceived during the nineteenth century as the work of individuals. Moreover, patent law developed other, more limited doctrines that provided some rights to inventors’ employers.

Today, however, most patentable inventions are invented by multiple inventors in a collaborative environment.[7] In fact between 1885 and 1950, the percentage of U.S. patents issued to corporations grew from 12% to at least 75%.[8] These numbers have only continued to increase in the past decade.[9] Moreover, the recently passed Leahy-Smith America Invents Act partially recognizes this change by permitting an “applicant for patent” to file a “substitute statement” instead of an inventor’s oath or declaration in certain circumstances.[10]

Nevertheless, patent law remains stuck in the past. The failure to modernize how patent law handles employee invention has led to a string of significant court opinions, including from the Supreme Court and the Federal Circuit, holding that employers had not received adequate assignments to their employees’ patented inventions and thus could not bring suit based thereon.[11] In order to resolve these issues and bring patent law into the twenty-first century, the Patent Act should be amended to borrow from the Copyright Act and adopt a principle similar to the work made for hire doctrine that would grant employers the rights to their employees’ inventions made within the scope of their employment.[12]

This article proceeds in four parts. Part I discusses the current state of copyright and patent law vis-à-vis employers’ rights in their employees’ intellectual labor. This part will compare copyright’s work made for hire doctrine to three patent law doctrines: the shop rights doctrine; the hired-to-invent doctrine, and the employee improvements doctrine. Part II describes the evolution of copyright law during the nineteenth century from the former regime, which vested employees with presumptive ownership of their work, to the current regime, which grants employers presumptive rights to their employees’ efforts. Part III describes patent law during the time that copyright law was changing so dramatically—including the development of the patent law doctrines described in Part I—and posits potential reasons that patent law did not make a similar move. In particular, (a) patent law’s development of the doctrines described in Part I provided similar benefits, although in the form of different rights, to those provided by copyright law’s work made for hire doctrine, and (b) the perceived nature of invention in the nineteenth century did not call for a unification and codification of those doctrines the way copyright law’s did. Finally, Part IV argues that patent law should modernize and develop an “inventions made for hire” doctrine.

I. IP and the Employer-Employee Relationship

It is well settled in the United States that copyright law and patent law treat legal title in the intellectual labor of employees differently.[13] Section A discusses the copyright law doctrine of work made for hire and its benefits for employers. Section B discusses doctrines that provide some of those benefits in patent law.

A. Copyright Law

Under the Copyright Act, title in a copyrightable work initially vests in the author or authors of a work.[14] However, “author” is a term of art with meaning beyond the creator of or “person who originates or gives existence” to a work.[15] In particular, where a “work made for hire”—another term of art—is concerned, the employer is “considered the author” unless the parties agree otherwise.[16] A work may be considered made for hire if (1) it was prepared within the scope of an employee’s employment, or (2) it is a certain type of commissioned work and the parties have so agreed previously.[17]

Whether the creator of a copyrightable work is an employee for purposes of the work made for hire doctrine is determined by looking to the common law doctrine of agency.[18] In Community for Creative Non-Violence v. Reid, the Supreme Court identified thirteen factors that it considered relevant to whether an individual was considered an employee as a matter of agency law.[19] The Supreme Court declared that “[n]o one of these factors [was] determinative,”[20] but at least one circuit has held that not all factors are created equal and some will be important in “virtually every situation” while others “will often have little or no significance.”[21] The more important factors are to be given “more weight in the analysis.”[22]

Once a work is considered made for hire, the employing or commissioning party enjoys several benefits over a work that is not considered made for hire, but rather is transferred to the employing party. First, unlike in patent law, it immediately becomes the owner of a legal right to the work.[23] In patent law, an inventor must first file an application with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“PTO”), which is then examined by a PTO employee to determine if the alleged new invention is entitled to a patent.[24] Copyrights, on the other hand, vest immediately once an original work of authorship is fixed in a tangible medium of expression.[25] For a company to gain an ownership interest in a copyrighted work not made for hire, the interest must be negotiated for and transferred in a signed written document.[26] When a work qualifying as a work made for hire is created, however, no negotiation or written instrument is required for that specific work because, for copyright purposes, as long as agency would hold that the work’s creator was an employee working within the scope of his employment, his employer is considered the work’s author.[27]

There are two subsidiary benefits to the immediate grant to the employer of a work’s copyrights. First, no court intervention is required to transfer the rights. As will be described below, in certain cases, patent law will grant employers rights in their employee’s patents, but to vest those rights the employee must still sign a document transferring ownership to his employer. If he refuses, a court order may substitute for the transfer. Second, the work made for hire doctrine allows a grant of rights without needing to define what is being granted. Whereas when a grant of rights is negotiated, the transferor may come back to the transferee to argue about which rights were actually transferred and the scope of the intended transfer.[28]

Second, an employer holding the rights in a work made for hire may register the work in the Copyright Office in its own name.[29] This is an optional but important step, because without registration a copyright infringement action may not be initiated,[30] and generally, statutory damages are not available for infringements prior to registration.[31]

Third, the work made for hire doctrine grants employers all of the rights associated with copyright ownership. Thus, they can exclude others from using the work, and leverage that right to extract rents in exchange for a license authorizing someone else to use the work.[32] Further, employers using works made for hire are authorized to then transfer their ownership of the works’ copyrights to another party, either in whole or in part.[33] They can also, of course, exercise any of the rights authorized under the Copyright Act itself, including creating derivative works.[34] One set of rights an employer is not granted under the Copyright Act, however, is the right to attribution and integrity granted for works of visual art.[35]

Fourth, the work made for hire doctrine also protects employers from future rights granted to authors. For example, the Copyright Act of 1976 granted authors the right to terminate transfers, but those new rights did not apply to creators of works made for hire because their employers were considered the author.[36] In addition, after the 1976 revisions, employers remained shielded from the exercise of the transfer termination provisions because no transfer is considered to have taken place under the work made for hire doctrine;[37] the employer was the work’s original “author.”

Fifth, the work made for hire doctrine grants employers certainty with regard to the duration of their copyrights. Works not made for hire subsist for the life of the author plus 70 years.[38] This means that those to whom the original author transfers must know the duration of the original author’s lifetime in order to calculate the duration of the copyrighted work’s term. Works made for hire, however, are merely granted a term of 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation, whichever expires first.[39] This time frame serves two functions. First, it simplifies the requirements of an employer to keep track of the duration of its copyrights. Second—grim though it may be—if the employee were to die within 25 years of publication or 50 years of creation, the employer would benefit from a longer copyright term than if the work were considered made for hire.[40]

Finally, the work made for hire doctrine applies to all works universally, regardless of the type of work or the employee’s level of contribution. In other words, a work created and conceptualized entirely by only one employee is treated the same as a work created by hundreds of employees, each of whom contributed minor improvements and expression to the work.

B. Patent Law

Some of the benefits described in the previous section are mirrored by certain patent law doctrines—or are irrelevant with regard to patents—but others have no patent law equivalent. Section A described eleven benefits associated with copyright law’s work made for hire doctrine: (1) grant of title without negotiation;[41] (2) grant of title without transfer/assignment; (3) grant of title without court intervention; (4) registrability in the employer’s own name; (5) exclusion of others from using the work and licensing rights in the work to others; (6) use of the work; (7) transfer of title to others; (8) protection from future rights granted to work’s creator; (9) shield from transfer termination; (10) benefits with regard to copyright term duration; and (11) universal application regardless of level of contribution.[42]

| Table 1: Work Made For Hire Benefits |

| No Negotiation |

| No Assignment from Employee |

| No Court Intervention |

| Registrability |

| Exclusion and Licensing |

| Use |

| Transfer to Others |

| Protection from Future Rights |

| Termination Shield |

| Duration |

| Universal Application |

It is immediately apparent that the benefits of the termination shield and duration are not relevant to patent law because patents are granted for a set term of years—whether the base of 20 years or an extended term due to regulatory or PTO review[43]—not tied to the inventor’s lifetime. Therefore, there would be no special duration benefits should an inventor’s employer be considered an “inventor” for purposes of the Patent Act. In addition, unlike copyright transfers, which as discussed above may be terminated upon notice, patent assignments are not subject to termination.[44]

The other benefits, however, require additional consideration. The three following sections describe modern patent law doctrines that give employers some, but not all, of the benefits of copyright law’s work made for hire doctrine.

1. Employer Use and Shop Rights

One of the benefits of the work made for hire doctrine is that an employer is guaranteed the right to make use of an employee’s creative work. Employers may receive a similar benefit from patent law’s shop rights doctrine.[45] However, because patent law describes negative rights, it is a protection against infringement actions by the employee patent holder and her assigns, and not an affirmative grant of use of the patented invention.

Shop rights arise when an employee, “during his hours of employment, [and] working with his [employer’s] materials and appliances, conceives and perfects an invention for which he obtains a patent.”[46] The courts have held that in such circumstances, the employee by force of law must give his employer a nonexclusive, royalty-free right to practice the invention.[47] The doctrinal basis behind the shop right remains fuzzy,[48] as courts have described it being based on (a) a license implied in fact,[49] (b) estoppel,[50] and (c) equity and fairness.[51]

Shop rights do not have the same scope as work made for hire, however. A shop right is not an ownership interest in the patent, which means that an employer does not have either the right to exclude others by threatening to sue for infringement or the right to file a patent application.[52] Similarly, a shop right is non-exclusive, which means that the employee patent holder is free to assign rights to others by granting them a patent license. In addition, a shop right is not transferable other than with the sale of the entire appurtenant business.[53]

| Table2: Work Made For Hire v. Shop Rights | |

| No Negotiation | ✓ |

| No Assignment from Employee | ✓ |

| No Court Intervention | ✓ |

| Registrability | |

| Exclusion and Licensing | |

| Use | ✓ |

| Transfer to Others | |

| Protection from Future Rights | |

| Termination Shield | n/a |

| Duration | n/a |

| Universal Application | ✓ |

2. Commissioned Invention and the Hired-to-Invent Doctrine

As mentioned in section A, under copyright law a work will be considered for hire if it was made by an employee within the scope of his or her employment. Similarly, patent law’s hired-to-invent doctrine grants an employer rights to the inventions of its employees if the employee was hired to invent them.

Under this doctrine, an employee hired to solve a particular problem or to invent in a certain field will forfeit his patent rights even without a written contract.[54] Just as in the work made for hire context, courts have established a number of factors to indicate whether an inventor has been hired to invent.[55] However, unlike work made for hire, the hired-to-invent doctrine requires the employee to assign any patent obtained; it does not vest title immediately in the employer upon invention.[56] Although, failure to assign after a court order to do so may result in the order having the same effect as an assignment.[57]

At first blush, this patent law doctrine would appear to accomplish much of what the copyright law work made for hire doctrine does. However, there are differences. First, work made for hire vests title in an employer immediately. The hired-to-invent doctrine merely obligates the inventor to assign the invention to his or her employer. True, no negotiation is required after the inventive activity occurs, but until an assignment is signed, the invention’s creator continues to hold the patent on the invention—albeit in trust for his employer. Furthermore, if the invention’s creator refuses to assign his patent rights, then a court order is required. Second, the doctrine is only effective against employees who are actually hired to invent. Employees who create an invention within the scope of their employment but who were not specifically directed to do so retain their patent rights.[58] Third, unlike the work made for hire doctrine, which permits an employer to file a copyright registration in its own name, the hired-to-invent doctrine still requires the patent application to be filed in the inventor’s name, even if the employer, as assignee, files a patent application on his behalf. Finally, as the employee is still considered the “inventor” under the Patent Act, it is possible for future rights to be given to the “inventor” that would not be automatically vested in the inventor’s employer. For example, in the copyright context, when the right to terminate transfers of ownership was introduced as a right of “authors,” it did not apply to those whose works were made for hire, as their employers were considered the “authors.” Similar rights could be granted to “inventors” that would affect the assignees of the inventors’ patent rights.

| Table3: Work Made For Hire v. Hired-to-Invent | |

| No Negotiation | ✓ |

| No Assignment from Employee | |

| No Court Intervention | |

| Registrability | |

| Exclusion and Licensing | ✓ |

| Use | ✓ |

| Transfer to Others | ✓ |

| Protection from Future Rights | |

| Termination Shield | n/a |

| Duration | n/a |

| Universal Application | ✓ |

3. Employer Inventions and Employee Improvements

In addition to the situation where an employer hires an employee to invent, an employer will also receive the benefit of insignificant improvements by his employees on inventions the employer has conceived of himself.[59] Under this doctrine, when an employer conceives of an invention, but receives ancillary suggestions or improvements from his employee, he retains all rights in the invention, including any employee improvements.[60] To qualify under the employee improvements doctrine, the employer must have had a “plan and preconceived design,”[61] and the improver must be an employee.[62]

The employee improvements doctrine provides a minimal step toward the work made for hire doctrine, but does not come anywhere close to providing a substitute. First, the doctrine still requires there to be an inventor. All the doctrine does is subsume improvements by another person into the inventive exercise of the employing inventor; it does not operate to grant an employing corporation rights. In addition, the improvements that are granted must be ancillary, so any benefits from the doctrine will be minimal. Thus, if the employee creates a non-ancillary invention or improvement, the employer still needs to qualify under one of the previous doctrines or negotiate an assignment. At base, the employee improvements doctrine determines whether an employee should be considered a joint inventor or not, which does not come close to achieving the same benefits of the work made for hire doctrine.

| Table4: Work Made For Hire v. Employee Improvements | |

| No Negotiation | ✓ |

| No Assignment from Employee | ✓ |

| No Court Intervention | ✓ |

| Registrability | ✓ |

| Exclusion and Licensing | ✓ |

| Use | ✓ |

| Transfer to Others | ✓ |

| Protection from Future Rights | |

| Termination Shield | n/a |

| Duration | n/a |

| Universal Application | |

Given that patent law never developed a doctrine that defaulted patent rights to an employer the way copyright law did, one is left to wonder why. Why is it that copyright law in the nineteenth century began to apply an employer presumption? And why did the courts not feel the need to apply a similar presumption in patent cases? Part II discusses the development of the work made for hire doctrine in the nineteenth century, and Part III discusses potential reasons that a similar doctrine was not developed in patent law.

II. Development of the Work Made for Hire Doctrine

The work made for hire doctrine predated the Copyright Act of 1976. In fact, although it was first codified in the Copyright Act of 1909,[63] Professor Catherine L. Fisk has claimed that the doctrine “neither was invented by the drafters of the 1909 Act, nor was it well recognized in the cases before 1909.”[64] Instead, between the American Civil War and the passage of the Copyright Act of 1909 the default rule in copyright cases quietly switched from employee ownership to employer ownership. Professor Fisk argues that this move was justified by “cloaking” artists in an “aura of . . . romantic genius” to argue for greater legal protection, while simultaneously “downplaying or ignoring individual creative genius so as to assert corporate ownership over those copyrighted works.”[65]

A. Antebellum

Prior to the American Civil War, the default—and essentially the rule—was that the employee author was the owner of his works.[66] In the early days of copyright, protection was of limited application. The first copyright act—the Copyright Act of 1790—only protected maps, charts, and books.[67] Among the books that received copyright protection were the books in which court decisions were reported. Thus, it was only natural for the first copyright cases concerning employment to involve books containing those decisions and the authors that authored them. In the first case involving an employed author, the author of twelve volumes reporting the caselaw of the United States Supreme Court assigned his copyrights to a publisher. The publisher then sued a subsequent case reporter for copyright infringement because he had produced a volume titled “Condensed Reports of Cases in the Supreme Court of the United States,” which included the work of the prior reporter.[68] The Supreme Court, noting that the original reporter had failed to satisfy the formality requirements, held that it could not confer common law copyright on the initial reporter. However, what is telling about the opinion is that it appears to assume that the original reporter—and not the publisher—would be entitled to the copyrights in his work, even though his status as an employee was uncertain at best.[69]

Later cases in the antebellum era involved school books,[70] theatrical works,[71] and cartography.[72] What is particularly interesting about this period of time is the courts’ clear pro-employee stance. In later decades, courts’ rhetoric would be inconsistent with the holdings of their decisions. While courts would claim to celebrate the genius and romanticism of the independent author, they would simultaneously grant first publishing houses and later employers the rights to that labor. During the antebellum nineteenth century, however, courts’ rhetoric praising the individual was consistent with the holdings of their decisions, which largely gave employees ownership of the copyrights in their works. The only cases where employers were held to have been granted copyrights in their employees’ works involved expressed contracts and cartography which, by its very nature, requires coordination among various individuals. True, smaller scale maps could be created by one person on their own, but for anything of a greater scale, coordination among various parties would be required.

B. The Nineteenth Century Postbellum

In the period during and after the American Civil War, courts began to hold that employers had been granted copyrights in their employees’ works, not by operation of contract, but based on the employment relationship. Particularly important to the discussion in Part III is that while cases originally held that the employment relationship granted an employer rights in his employees’ work by virtue of the involvement of a corporate president, later cases created the legal fiction of the company as author.[73]

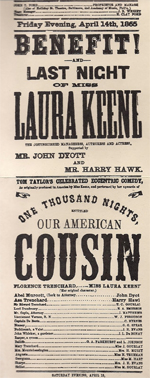

In the postbellum period, like the antebellum period, the relevant cases generally involved legal publications,[74] as well as theatrical works.[75] One of the theatrical work cases is particularly important for the purposes of this article. In Keene v. Wheatley, the court ruled against the plaintiff-employer on many of her arguments, but with regard to ownership of one of her employee’s works, the court stated:

Here, [the employee], while in the general theatrical employment of the [employer], engaged in the particular office of assisting in the adaptation of this play; and made the additions in question in the course of his willing performance of this duty. [The employer] consequently became the proprietor of them as products of his intellectual exertion in a particular service in her employment.[76]

For this proposition, the court did not rely on copyright law. Instead, the court looked to patent law, and determined that since “[w]here an inventor, in the course of his experimental essays, employs an assistant who suggests, and adapts, a subordinate improvement, it is, in law, an incident, or part, of the employer’s main invention,” the plaintiff in Keene was entitled to the “literary proprietorship” of her employee’s work.[77]

In the eyes of the Keene court, the employee was merely adding minor enhancements akin to the patent doctrine of employee improvement. Yet, over time the doctrine of work made for hire found increasing judicial support and eventually became a default rule in favor of employers.[78] Over the next several years, this new doctrine was mentioned in dicta, but in no case did a court rule that an employer possessed rights over its employee by virtue of the default rule.[79]

Instead, the presumption was switched surreptitiously. In Callaghan v. Myers, for example, while holding that a court reporter-employee held the copyrights in his work instead of his government employer, the Supreme Court determined that this was the case only due to “a tacit assent by the government to his exercising such privilege,”[80] This shift in emphasis made employer ownership a presumption that was only rebutted by tacit agreements and expressed contracts.

Why did the courts make this shift? Professor Fisk posits three potential factors:

[1] Courts might have felt that a default rule of employer ownership was more likely to reflect the intent of most parties and wanted to save the parties the trouble of negotiating for employer ownership. . . . [2] [C]ourts might have begun to see employers as possessing a stronger moral claim and believed that any employee who planned to assert copyright ownership ought to be forced to disclose that intent and negotiate for it. . . . [3] [A]s changing assumptions about the nature of authorship strengthened the rhetorical force of the employer’s claim, a default rule of employer ownership might have seemed more intrinsically appealing, irrespective of whether the parties might negotiate around it.[81]

In response to the shifting sands of copyright law doctrine of the nineteenth century, one might expect that parties would have begun contracting around the default rules, but two factors may have made contracting prohibitively difficult:

First, the costs of transacting might be high when the parties have to discuss something as touchy as authorship. Employers might have been afraid to alienate employees by demanding assignment of the copyright, preferring to run the risk of litigation later. Employees may have lacked legal sophistication to realize that it was necessary to contract for copyright ownership. Second, the instability of the law may have made enforcement of any contract they did reach highly uncertain.[82]

In any case, by the nineteenth century, the work made for hire doctrine was in the wind, whether because of changes in the parties themselves, or merely the impressions of those sitting on the bench.

C. Corporate Ownership and Codification

The work made for hire doctrine was codified by Congress in 1909, but its foundations had existed prior to that time. As described in section B, the concept of authorship and ownership of copyright were shifting over the last half of the nineteenth century. However, it was not until 1885 that a court held that a corporation, and not an individual employer, held the copyrights in a work.[83] It was at this time that the legal fiction arose that a corporation could be an author. This idea makes sense when viewed one way: corporations are merely collections of individuals working toward, generally, hierarchically determined joint goals. However, it flies in the face of the entire notion of the individual romantic author.

The concept behind the expression embodied in a copyrightable work can be created by any number of different people as it moves through the corporate process. This is particularly clear today when one looks at the large corporations behind music, television, and film.[84] These corporations are made up of hundreds of thousands of employees, and even more independent contractors. To produce one blockbuster film may require hiring and coordinating thousands of individuals, each of whom may contribute to a portion of the film. Without the work made for hire doctrine, these companies would have to rely on a messy web of contracts and the employee improvements doctrine, and even then, it is unlikely that they would be assured that all the relevant rights had been secured.

By 1899, however, the courts had come to realize the need for a doctrine that allowed corporate employers to control the copyrights in the works of their employees by default. In Collier Engineer Co. v. United Correspondence Schools, a salaried employee hired “to compile, prepare, and revise . . . instruction and question papers” had moved to a new employer and prepared similar materials.[85] His former employer made a motion for a preliminary injunction, which the court denied, but in so doing determined that the employer was entitled to any copyright in the original materials.[86] This idea of protecting employers when their employees move to other employers will resurface in Part III as a justification for employer ownership of patent rights.

Later cases embraced the idea that when an employer hired individuals to produce copyrightable works, the copyrights in those works were granted to the employer.[87] In this way, by the turn of the century, copyright law and patent law had developed fairly parallel doctrines with regard to employee works and inventions. In 1909, however, the Copyright Act was revised to codify the work made for hire doctrine by adding the following language:

[T]he word ‘author’ shall include an employer in the case of works made for hire.[88]

By including employers of those that create works made for hire within the definition of the term “author,” Congress continued in the direction the courts had been heading, but went farther by creating an explicit employer presumption. Professor Fisk identifies three reasons for this change: (1) an ease in drafting the Act, (2) avoiding constitutionality challenges, and (3) ensuring that copyright ownership would vest initially in employers so they could benefit from copyright renewals.[89]

And that, ladies and gentlemen, was history. Since 1909, work made for hire has remained a mainstay of American copyright law.

Yet, despite over one hundred years of the work made for hire doctrine in copyright law, patent law remains based on the rule that only the individuals that create an invention can be considered inventors. Moreover, for an employer to claim patent rights, he must either negotiate an assignment, or rely on one of the doctrines discussed in Part I.B.: shop rights, hired-to-invent, or employee improvements. Barring one of these options, an employer holds no rights in a patent absent a written assignment. Part III will explore the patent cases of the late nineteenth century, and posit potential reasons that patent law did not take a similar route.

III. Employment in Patent Law

As previously described, patent law never developed a doctrine that provided all of the benefits of copyright law’s now well-established work made for hire doctrine. This divergence between the two disciplines can be explained by two factors. First, inventive activity in the nineteenth century was perceived to be individualized and not to require significant coordination among individuals. Second, patent law developed the three doctrines described in Part I.B., which provided satisfactory protection to employers who wanted to continue using their employees’ inventions.

A. Antebellum

In order to understand the nature of inventive activity during the nineteenth century, one must understand that fundamental shifts were occurring in society at the time that changed both who the inventors were and what they were inventing. The United States has always been a country of inventors. In fact, both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson are credited with numerous inventions, including plows, adjustable writing desks and swivel chairs.[90] However, at the end of eighteenth century, there were “probably no more than 300 people who we would now class as scientists in the entire world,”[91] By 1800, there were about a thousand, and by 1900 there were approximately 100,000.[92] Due to the growth in the number of scientists, science began to shift from “a gentlemanly hobby, where the interests and abilities of a single individual [could] have a profound impact, to a well-populated profession, where progress depend[ed] on the work of many individuals who [were], to some extent, interchangeable.”[93]

Similarly, the number of non-scientist inventors blossomed throughout the nineteenth century leading to an increased ability to appreciate the “interplay between science and technology, particularly in the fields of electricity and engine building,” which “led to a host of new practical machines that changed communications, transportation, the home, the workplace, and the farm,”[94] For example, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, America remained a nation of farmers who used the same hand implements that had been used for centuries to harvest their crops and who would travel primarily by horse or boat.[95] In the time before the Civil War, however, non-scientist inventors made many advances, including the invention of the steamboat, farming machinery, the telegraph, and synthetic materials.[96] Such advances were only possible due to the increased interplay between science and technology that continued to grow throughout the nineteenth century.[97] These developments also led to societal changes, including increased prosperity and the end of slavery as new equipment was developed that could perform the work better and more cheaply.[98]

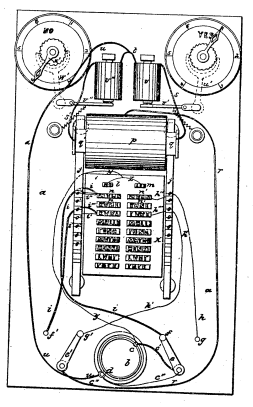

Despite the democratization of science and invention in the nineteenth century, however, inventive activity continued to be considered the work of individuals. In fact, there are “no reported cases before 1843 in which an employer claimed, as against an employee, ownership of a patent because the inventor had been working for him at the time of the invention,”[99] Thus, in the nineteenth century, the general perception was that inventorship was the work of certain individuals, who were considered the great men of the time. One visual example of this mentality is Christian Schussele’s 1857 painting titled Men of Progress, which depicts Benjamin Franklin overlooking nineteen nineteenth century inventors:[100]

Despite this public perception, however, the reality was that even these great men had assistance in creating their famous inventions. Among those depicted in Schussele’s painting is Charles Goodyear, who is remembered for his invention of vulcanized rubber in 1839.[101] He received a patent on his process in 1844,[102] and almost immediately became embroiled in patent litigation.[103] Not only was Goodyear forced to litigate against his competitors, however, but also against his own employees, one of whom attempted to patent one of Goodyear’s inventions.[104] Fortunately for Goodyear, despite recognizing a presumption in favor of the employee—who actually made the machine—the courts considered Goodyear’s employee’s activities to have been at Goodyear’s direction, and thus, they determined that it was Goodyear, and not his employee, that was the true inventor.[105]

Despite the favorable result for Goodyear, the case only underscored the presumption that employees owned their inventions, as the court continued to articulate employee-ownership as the general presumption in such cases. Thus, time and time again, courts were required to find exceptions in order to protect employers from the presumption’s consequences. For example, in 1843 the Supreme Court, in McClurg v. Kingsland, determined that a license or grant from the employee to the employer may be presumed by virtue of the fact that the employee:

was employed by the defendants . . . receiving wages from them by the week; while so employed, he claimed to have invented the improvement patented, and after unsuccessful experiments made a successful one . . . the experiments were made in the [employer’s] foundry, and wholly at their expense, while [the employee] was receiving his wages, which were increased on account of the useful result.[106]

This implied license, or shop right, prevented the assignees of the employee’s patent from bringing suit against the former employer for infringement when all the employer was doing was continuing to use the process it had been using prior to the employee’s departure.[107] The Court reached this result without requiring an assignment of the patent. Rather, the Court held that the plaintiffs took their assignment from the employee subject to his license to his former employer.[108] As such, McClurg is generally thought of as the first shop rights case.[109] It can also be seen as a fairly pro-employee case, for the employer received no rights to the invention other than the right to use it despite the fact that the employee would not have been able to make his improvement but for his employer’s time, money and equipment.[110]

During this same time period, other inventors were creating major innovations in both science and industry. For example, in 1844 Samuel Morse—also depicted in Men of Progress—connected the first intercity line between Washington and Baltimore and sent the message, “What hath God wrought!”[111] Moreover, scientists were making significant advances in electric theory, evolution, and thermodynamics.[112] Similarly, in the decade that followed, solo inventors continued to be credited with major breakthroughs in both science and industry. For example, during the 1850s, Heinrich Geissler is credited with the leaps forward that resulted in the invention of the vacuum tube.[113] Further, the 1850s saw huge advances in telecommunications technology, including Morse’s testing of the first transatlantic telegraph cable.[114] Even Abraham Lincoln took the time to consider the discoveries, inventions and improvements that resulted from America’s willingness to observe, reflect and experiment.[115]

Despite the attribution of these major advances to individual inventors, the reality was that even in the 1840s, teams of workers were working together to develop new technologies, which “somewhat undermine[s] the heroic mythology surrounding the great individualistic and entrepreneurial American inventors,”[116] The dichotomy between the myth of the sole inventor and the reality that inventive activity was being carried out by groups of individuals in many ways mirrors the shift that was occurring in copyright law at that time. However, instead of acknowledging that multiple individuals were involved in the inventive process, courts turned a blind eye to the significant contributions employees were making to their employers’ inventions and dismissed those contributions as small modifications.[117] In King v. Gedney, for example, the court disregarded the following evidence as “vague and equivocal,” and instead determined that the employer “might have” given the employee—a draftsmen and general foreman—general directions about the improvement:

[The employee] was the foreman, and directed the making the alterations in the factory. [The employer] gave him no directions in relation to those alterations; [another employee] asked him for directions during the time that he was making alternations, and his answer was, ‘I do not know anything about it; go to [the employee].’ He said it was [the employee’s] improvement, and he knew nothing about it; if it did not work it was [the employee’s] fault; [the other employee] must go to him for all instructions. [The other employee] did not hear [the employer] give directions to any of the workmen in the shop. He has seen [the employer] and [the employee] conversing together at the factory, when chalk marks were made upon the floor by [the employee] to convey to [the employer] the manner in which he was going to prosecute the work.[118]

The court determined that if the general idea was the employing inventor’s, then the employee “could only be considered as acting as [his] servant,” and held the employer to be the original and sole inventor.[119]

Thus, by crediting employers with being sole inventors, courts were able to continue to articulate the presumption that those who do the actual inventing will own the rights to their inventions. However, as employees became more and more involved with the inventive process, courts would find it increasingly difficult to rely on the employee improvements doctrine to rebut the presumption of employee ownership.[120]

B. The Nineteenth Century Postbellum

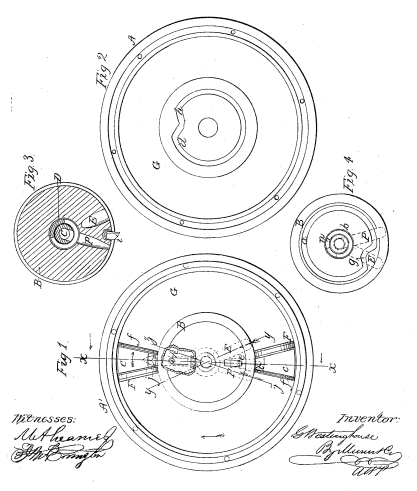

American invention did not stop during the American Civil War. In fact, the war spurred increased invention, particularly in agriculture. For example, Cyrus McCormick—another famed inventor depicted in Men of Progress—developed a reaper in 1861, which allowed northerners to increase food production “to the highest levels of surplus ever known” even though they had fewer farm hands due to the war.[121] Similarly, in the mid-1860s, scientists were making major advances in chemistry and thermodynamics.[122] Then, in 1865, George Westinghouse received his first patent for a rotary steam engine, followed by patents for railroad frogs and air brakes.[123] A few years later, a “self-taught practical innovator” by the name of Thomas Alva Edison would apply for his first patent.[124] Edison is a particularly interesting example of a nineteenth century inventor, because it is well documented that he “regularly employed not only mechanics and craftsmen but also college-trained chemists and engineers in his invention workshop,”[125]

In some ways, then, it is not surprising that the Supreme Court first recognized the employee improvements doctrine in its 1868 Agawam Co. v. Jordan opinion. In Agawam, an inventor named John Goulding hired a blacksmith, Edward Winslow, to help in his machine shop.[126] Goulding had been working on his invention and was at the point of experimentation when Winslow, having visited another factory, made a suggestion of replacing a piece of Goulding’s invention with a spool and drum.[127] Goulding went back and forth about the value of the suggestion, but after making another modification to make the change practicable, he adopted Winslow’s suggestion.[128]

The new invention was patented and eventually assigned to the plaintiff who then sued the Agawam Woolen Company for infringement.[129] Agawam defended, in part, by arguing that it was Winslow, and not Goulding, that invented the improvements for which the patent was granted.[130] The Court held that Goulding’s claim to invention of the patent was sustained, because all that Agawam could prove was that Winslow suggested the spool and drum—an “auxiliary” part of the invention.[131] In handing another victory to an employer, however, the Court continued to recite that the general presumption is that employees hold rights to their inventions.[132]

Similarly, as discussed above, during this time employers in copyright cases began to see the presumption switch from employee ownership to employer ownership. For example, five years prior to Agawam, the influential case of Kenne v. Wheatley was decided in favor of the employer relying on an employee improvements-type argument to grant a theater proprietor the copyrights to a play adapted by her and her theatrical company.[133] Whereas in theater it was undeniable that multiple individuals were required to develop new materials and produce it for the stage, invention in the 1870s continued to be perceived as the work of individuals with minimal help from employees instructed to carryout manual labor.

Significant changes, however, were on the horizon for those industries that employed workers to design and construct their products. The “United States began to develop a single price and market system,” which led to capital intensive industries that “employed workers who owned no tools and had few skills, leading to social inequalities that created new political crises,”[134] Those inequities led to the formation of labor unions, which employed a variety of tactics to effect the status of workers in this country. “The decades from the 1870s through the early 20th century saw one disruptive strike after another and the beginning of the appeal of ideologies and reform strategies that would characterize the labor movement—agrarian reform, populism, socialism, anarchism, and progressive reformism.”[135]

Despite these changes, inventive activity in the United States soldiered on. For example, Edison—who, as discussed above, employed a variety of workers in his invention workshop[136]—had filed for patents on 21 inventions by 1871.[137] As inventive activity began to involve more complex technology, the proportion of inventions devised by solo inventors continued to decline.[138] Perhaps in recognition of these changes, the Supreme Court began to hint at a willingness to recognize employers’ ownership of patented inventions that they hired employees to create.[139]

Nevertheless, there were limits to the Court’s willingness to grant patent rights to one who employed another to invent. In Collar Co. v. Van Dusen, for example, the Supreme Court determined that the plaintiff, despite employing a set of paper-makers to create a paper collar that would be perceived as a real starched linen collar, was not entitled to a patent because only the paper-makers had invented something patentable.[140] The plaintiff had argued that the paper-makers had received inspiration and direction, but the Court determined that the paper-markers had provided the whole improvement and therefore the plaintiff had no rights to their invention under Agawam’s ancillary discoveries rule.[141]

Despite its use of the terms “employer” and “employee,” however, the Collar case is better understood as concerning, using our modern parlance, independent contractors, who, even if Collar was a modern copyright case, would be unlikely to fall within the work made for hire doctrine. Rather than inspiring and directing the paper-makers’ improvement, the patentee derived all of the improvements he attempted to patent from the paper-makers. Similarly, other courts in the 1870s held that if an employee’s invention was outside the employee’s inventive arena, the employer would receive no more than a shop right to the invention.[142]

By the 1880s, “farmers and industrial workers represented a force for political insurgency that began to coalesce into new movements that threatened to change the nature of society,”[143] These movements reflected a general anti-monopoly and big business sentiment at the turn of the century, as they began to lead to discussions of new government regulations “to control railroad rates and other large enterprises . . . to address the growing power of bankers and railroad magnates,”[144] At the same time, entrepreneur inventors, like Westinghouse, were beginning to build empires of their own from their own companies and inventions, as well as those of others.[145] These companies employed various individuals who developed patentable inventions during their employment.

During the remainder of the nineteenth century, disputes over employees’ inventions became more frequent and led to cases that further developed the shop right[146] and employee improvements doctrines.[147] The courts, however, failed to develop a mechanism for dealing with employees that were explicitly hired to invent,[148] until the hired-to-invent doctrine was formally recognized by the Supreme Court in 1924.[149] Also, the rise of the corporate form introduced additional complications,[150] such as whether a shop right could be assigned.[151] Despite these developments, however, in not one of these cases was an employing company considered an “inventor” by virtue of its employees’ activity. Rather, for a company to receive patent ownership, an employee needed to assign it his or her rights.

By the turn of the century, each and every person in the United States had been affected by the inventions of the nineteenth century. In particular, the poor were being put to work in factories using newly invented machinery and tools. Even the middle classes indirectly benefited from the benefits of the day:

For the middle classes, such as physicians, attorneys, engineers, academics, journalists, and managers, whose employment was less dependent on machinery and tools than on their education, the new technologies provided new sources of entertainment, comfort, and opportunities. By 1890, a person who worked in such a profession could come home, switch on the electric light, make a phone call, go to the refrigerator and take out a cold beer, light a factory-made cigarette with a safety match, then sit down to listen to a phonograph record while reading a newspaper with news of the day from all over the planet. It was a new world, for none of those experiences had been possible 40 years earlier, even to the wealthy.[152]

IV. Is Patent Law Stuck in the Past?

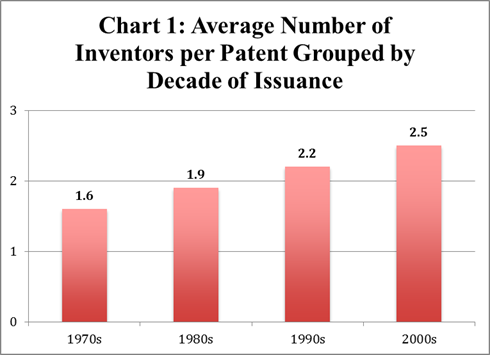

For inventors in the twentieth century, more and more inventive activity would occur within corporate settings. However, patentable inventive activity would continue to be credited to individuals, not groups, until late into the century. In fact, the average number of inventors per patent would not begin to change dramatically until the 1970s, when a “dramatic increase in the proportion of ‘highly collaborative’ inventions” would drive the average up:[153]

Yet, despite the fact that today the “ordinary inventor is . . . a joint inventor who invents as part of a team,”[154] patent law continues to require that corporate employers receive assignments from their employees in order to effect a transfer of the ownership of the employees’ patent rights.

In Part II, several reasons behind copyright law’s move toward the work made for hire doctrine were posited: (1) courts were attempting to reflect the intent of the parties; (2) courts felt that employees were in the best position to determine ex ante whether they intended to assert copyright ownership; (3) changing notions of the nature of authorship; (4) ease of statutory drafting; (5) avoiding constitutional concerns; and (6) concern about renewal terms.

Three of these reasons simply do not apply to patent law. First, patents in the United States do not have renewal terms. Second, the copyright statute was being revised in 1909 for reasons beyond the codification of the work made for hire doctrine. The patent statute, by contrast, was not significantly revised until 1952. Without an independent push to redraft the Patent Act, the need to ease statutory drafting was absent, and constitutional concerns in granting patent rights to non-“inventors” would not need to be addressed. As for the remaining reasons for the shift in copyright law, patent law simply did not share those factors.

First, the perceived nature of inventive activity in the nineteenth century did not lend itself to an argument for the need of a doctrine like work made for hire. As discussed in Part II, copyrighted works grew in complexity over the course of the nineteenth century. While copyrighted works were originally only embodied in single author books, they steadily grew to include complicated works involving the input of the multiple creative individuals. In particular, the creation of maps and theatrical works required coordination among multiple parties to insure that works could be exploited. Once the 1909 Act was passed, that complication grew exponentially as additional works were brought under the copyright statute.

The perception of inventive activity in the nineteenth century, on the other hand, did not appear to require significant coordination among parties. Rather, credit for advances was given to individual inventors, whether or not they, like Edison, employed others in their invention workshops. Moreover, even in the nineteenth century, most patents were on incremental improvements of existing technologies, which made it even more likely that the number of individuals involved in each inventive push forward would be small. Further, even if an invention required multiple individuals to reduce it to practice, the individual credited with the invention could subsume any other inventive activity into his invention under the employee improvements doctrine. In fact, in 1916, three-quarters of U.S. patents were issued to individuals.[155] Thus, the need to coordinate among multiple individuals that existed in copyright law in the nineteenth century did not exist in patent law.[156]

Second, the existing doctrines that had developed, including the hired-to-invent doctrine, provided sufficient ex ante protection to employers. The shop rights doctrine, which was well established in the early part of the century, provided employers with a way of ensuring that their expectations were met. Unlike today where many organizations that own patent rights merely license those rights to others to use, in the nineteenth century, most companies used patent rights merely to exclude competitors while they themselves developed products to sell to consumers. Without the need to license, companies merely needed the right to use, which the shop rights doctrine provided. Moreover, as described above, when an inventor did use assistance in the process of developing his invention, the employee improvements doctrine protected him from needing to secure rights from each assistant in his workshop. As long as the inventor couldn’t be seen as deriving his invention from someone else, he could be fairly content that his rights in the invention would be secure.

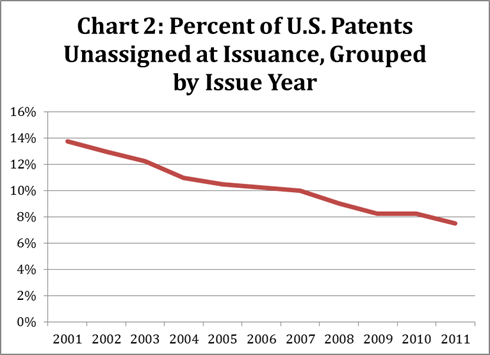

Finally, by the end of the nineteenth century, employers were securing contracts with their employees that included provisions requiring the assignment of any patented inventions later developed.[157] In 1885, only 12% of U.S. patents were issued to corporations.[158] By 1950, it had grown to 75%, and by the 1980s, 84% of U.S. patents were assigned to corporations, “usually the employer of the actual inventor,”[159] In the past decade, those efforts have become increasingly successful.[160]

In fact, it will come as no surprise that the Intellectual Property Owners Association’s list of top patent owners does not include the name of a single individual.[161] Further, by the turn of the century, when an employer hired an inventor, the hired-to-invent doctrine would require the inventor to assign their rights to the employer.

Despite the protection of the existing patent law doctrines that give employers some of the benefits of the work made for hire doctrine, it is clear from Table 5 that not one doctrine captures all of the benefits from that doctrine:[162]

| Table 5: Work Made For Hire Benefits v. Patent Doctrines | |||

| Shop Rights | Hired-to-Invent | Employee Improv. | |

| No Negotiation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| No Assignment from Employee | ✓ | ✓ | |

| No Court Intervention | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Registrability | ✓ | ||

| Exclusion and Licensing | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Use | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Transfer to Others | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Protection from Future Rights | |||

| Termination Shield | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Duration | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Universal Application | ✓ | ✓ | |

Moreover, as recent cases make clear, companies cannot rely on the patent law doctrines and contracts with their employees to ensure ownership of the rights to their employees’ inventions.[163] For example, the Supreme Court recently held that although an inventor working as a research fellow at Stanford University signed a Copyright and Patent Agreement that stated that he “‘agree[d] to assign’ to Stanford his ‘right, title and interest in’ inventions resulting from his employment at the University” and written assignments of rights, which Stanford used to file several patent applications, Stanford did not receive the inventor’s patent rights because he signed a Visitor’s Confidentiality Agreement that provided that he “‘will assign and do[es] hereby assign’ to Cetus his ‘right, title and interest in each of the ideas, inventions and improvements’ made ‘as a consequence of [his] access’ to Cetus” between signing the CPA and the assignments.[164] Further, many modern employers intend to license, rather than use, their employees’ inventions, which a shop right would not permit.

Similarly, in Abbott Point of Care Inc. v. Epocal Inc., Abbott filed a patent infringement suit against Epocal, a competitor in the diagnostic field, alleging infringement of patents that “cover systems and devices for testing blood samples,”[165] Epocal, however, was founded by Dr. Imants Lauks, the named inventor of the patents at issue and a former employee of Abbott’s predecessors.[166] Despite the fact that Dr. Lauks had entered into two employment agreements, one of which contained a provision requiring him to assign all of his rights to any inventions that he might conceive, the Federal Circuit determined that Abbot did not hold rights to the patents and, thus, lacked standing to bring the lawsuit.[167] The court determined that Dr. Lauks had resigned from his previous employment in 1999, and that while the consulting agreement that he entered into after his resignation stated that various provisions of Dr. Lauks’ employment agreement remained in effect, it did not address invention assignments or obligations.[168] Thus, the two patent applications Dr. Lauks filed after entering into the consulting agreement did not belong to Abbot.[169]

Additionally, despite the high assignment rate discussed above, when a patent assignment is found to be ineffective, the consequences can be extreme. This is particularly true where the employer acts on its belief that an assignment is effective and incurs costs associated with the patented technology, only to learn that they do not, in fact, hold any patent rights.

As such, it is time for patent law to come to terms with the fact that it is stuck in the past and adopt an inventions made for hire doctrine. To do so, Congress need only pass an act amending two sections of the Patent Act. First, Congress would add a subsection (c) to 35 U.S.C. § 111 as follows:

(c) In the case of an invention made for hire, the employer is considered the inventor for purposes of this title, and, unless the parties have expressly agreed otherwise in a written instrument signed by them, owns all patents rights to the invention.

Second, Congress would add a subsection (f) to 35 U.S.C. § 100 as follows:

(f) An “invention made for hire” is an invention invented or discovered by an employee within the scope of his or her employment.

Whether an individual is an employee for purposes of the invention made for hire doctrine will be determined by looking to the same common law doctrine of agency that the Supreme Court identified in Community for Creative Non-Violence v. Reid.[170] Moreover, there is over two decades of caselaw interpreting agency doctrine in light of the Copyright Act and over a century of caselaw interpreting the work made for hire doctrine for courts to rely on in implementing this new provision.[171]

Conclusion

As this article has suggested, patent law remains stuck in the past by continuing to rely on the rhetorical device that modern invention is performed by individual inventors in their garages, when, in fact, most patentable inventive activity occurs in corporate and university settings. Moreover, contrary to popular perception, most individuals who would be labeled “inventors” in the twenty-first century are employees of a corporate entity and assign their patent rights to their employer. Nevertheless, patent law continues to require written assignments to give employers ownership of their employees’ inventions. While that formulation may have made sense when invention was credited to individuals and required little coordination among inventors, it no longer does. Rather, employers should be able to feel secure in the knowledge that any inventions invented or discovered by their employees within the scope of their employment are owned by the party that financed and supported them (i.e., their employers). As such, it is time for the Patent Act to be amended to borrow from the Copyright Act and adopt an inventions made for hire doctrine.

[2] See Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. § 201(b) (2006) (“In the case of a work made for hire, the employer or other person for whom the work was prepared is considered the author for purposes of this title, and, unless the parties have expressly agreed otherwise in a written instrument signed by them, owns all of the rights comprised in the copyright.”).

[3] See United States v. Dubilier Condenser Corp., 289 U.S. 178, 188 (1933) (noting that invention is “the product of original thought”); Solomons v. United States, 137 U.S. 342, 346 (1890) (“[W]hatever invention [an inventor] may thus conceive and perfect is his individual property.”); Gayler v. Wilder, 51 U.S. 477, 493 (1851) (“[T]he discoverer of a new and useful improvement is vested by law with an inchoate right to its exclusive use, which he may perfect and make absolute by proceeding in the manner which the law requires.”); 8 Chisum on Patents § 22.01 (2012) (“The presumptive owner of the property right in a patentable invention is the single human inventor . . . .”); see also Patent Act of 1952, 35 U.S.C. § 152 (2006) (“Patents may be granted to the assignee of the inventor of record in the Patent and Trademark Office, upon the application made and the specification sworn to by the inventor, except as otherwise provided in this title.”); id. § 261 (“Applications for patent, patents, or any interest therein, shall be assignable in law by an instrument in writing.”); Bd. of Trustees Trs. of Leland Stanford Junior Univ. v. Roche Molecular Sys., Inc., 131 S. Ct. 2188, 2192 (2011) (“Since 1790, the patent law has operated on the premise that rights in an invention belong to the inventor.”); Dubilier Condenser, 289 U.S. at 187 (“A patent is property and title to it can pass only by assignment.”); 8 Chisum on Patents § 22.01 (2012) (“The inventor . . . [may] transfer ownership interests by written assignment to anyone . . . .”).

In fact, only the actual inventor is entitled to a patent, and only the inventor or someone he has assigned his patent rights to in writing may file a patent application, which in either case must be made on the inventor’s behalf. See 35 U.S.C. § 111(a)(2)(C) (“Such application shall include . . . an oath by the applicant as prescribed by section 115 of this title.”); id. § 115 (“The applicant shall make oath that he believes himself to be the original and first inventor of the process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or improvement thereof, for which he solicits a patent . . . .”) (emphasis added); id. § 118 (“Whenever an inventor refuses to execute an application for patent, or cannot be found or reached after diligent effort, a person to whom the inventor has assigned or agreed in writing to assign the invention or who otherwise shows sufficient proprietary interest in the matter justifying such action, may make application for patent on behalf of and as agent for the inventor . . . and the Director may grant a patent to such inventor . . . .”) (emphasis added).

[4] Dubilier Condenser, 289 U.S. at 189; see also Stanford, 131 S. Ct. at 2196 (“We have rejected the idea that mere employment is sufficient to vest title to an employee’s invention in the employer.”).

[5] Certainly copyrights and patents share an affinity due to their finding support in the same clause of the Constitution. U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 8 (“The Congress shall have Power . . . [t]o promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries . . . .”).

[6] As described below, in the nineteenth century, copyright law had a strong presumption of employee ownership, which slowly moved to an employer presumption that was finally codified in the twentieth century. See infra Part II. Patent law, on the other hand, developed various doctrines that permitted employers to be considered the owners of patent rights in certain circumstances, but not in others. See infra Part III.

[8] David F. Noble, America by Design: Science, Technology, and the Rise of Corporate Capitalism 87 (Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. 1977).

[9] Dennis Crouch & Jason Rantanen, Assignment of US Patents, Patent Law Blog (Patently-O) (Dec. 18, 2011, 9:07 PM), http://www.patentlyo.com/patent/2011/12/assignment-of-us-patents.html.

[10] Leahy-Smith American Invents Act, Pub. L. No. 112-29, § 4, 125 Stat. 284, 294 (2011) (“A substitute statement . . . is permitted with respect to any individual who—(A) is unable to file the oath or declaration . . . because the individual—(i) is deceased; (ii) is under legal incapacity; or (iii) cannot be found or reached after diligent effort; or (B) is under an obligation to assign the invention but has refused to make the oath or declaration required. . . .”) (emphasis added); see also Dennis Crouch, AIA Shifts USPTO Focus from Inventors to Patent owners, Patent Law Blog (Patently-O) (Aug. 14, 2012, 9:35 AM), http://www.patentlyo.com/patent/2012/08/aia-shifts-usptos-focus-from-inventors-to-patent-owners.html (describing the shift).

[11] See Stanford, 131 S. Ct. 2188 (2011) (holding that Stanford did not hold the rights to a patent that was allegedly infringed by Roche’s HIV test kits); Abbott Point of Care Inc. v. Epocal Inc., 666 F.3d 1299 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (affirming the dismissal of Abbott complaint for lack of standing to bring suit based on blood sample testing patents).

[12] Patent law and copyright law borrowing from each other is nothing new. The Supreme Court borrowed patent law’s construction of secondary liability to inform its copyright decision in Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios. 464 U.S. 417, 439 (1984) (“There is no precedent in the law of copyright for the imposition of vicarious liability on such a theory. The closest analogy is provided by the patent law cases to which it is appropriate to refer because of the historic kinship between patent law and copyright law.”). That analysis was then expounded on in the copyright case of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd., 545 U.S. 913 (2005), and then the copyright focused construction was used as precedent in later patent cases. See, e.g., Ricoh Co. v. Quanta Computer Inc., 550 F.3d 1325, 1336–40 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (citing Sony and Grokster to determine the standard for contributory infringement); DSU Med. Corp. v. JMS Co., 471 F.3d 1293, 1303–04 (Fed. Cir. 2006) (same).

[13] 3 R. Carl Moy, Moy’s Walker on Patents § 10:17 (4th ed. 2012).

[14] Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. § 201(a) (2006) (“Copyright in a work protected under this title vests initially in the author or authors of the work. The authors of a joint work are coowners of copyright in the work.”).

[15] Oxford English Dictionary (2d ed. 1989).

[16] 17 U.S.C. § 201(b) (“In the case of a work made for hire, the employer or other person for whom the work was prepared is considered the author for purposes of this title, and, unless the parties have expressly agreed otherwise in a written instrument signed by them, owns all of the rights comprised in the copyright.”).

[17] Id. § 101 (“A ‘work made for hire’ is—

(1) a work prepared by an employee within the scope of his or her employment; or

(2) a work specially ordered or commissioned for use as a contribution to a collective work, as a part of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, as a translation, as a supplementary work, as a compilation, as an instructional text, as a test, as answer material for a test, or as an atlas, if the parties expressly agree in a written instrument signed by them that the work shall be considered a work made for hire.”).

For example, comic book authors generally are required to sign agreements establishing that their work is commissioned as a work made for hire. See Joshua L. Simmons, Catwoman or the Kingpin: Potential Reasons Comic Book Publishers Do Not Enforce Their Copyrights Against Comic Book Infringers, 33 Colum. J.L. & Arts 267, 272 (2010) (describing comic book work made for hire agreements and caselaw).

[18] Cmty. for Creative Non-Violence v. Reid, 490 U.S. 730, 750–51 (1989) (holding the sculpture at issue was not a work made for hire, because the sculptor was an independent contractor and CCNV could not satisfy Section 101(2)).

[19] Id. at 751–52 (“In determining whether a hired party is an employee under the general common law of agency, we consider [1] the hiring party’s right to control the manner and means by which the product is accomplished. Among the other factors relevant to this inquiry are [2] the skill required; [3] the source of the instrumentalities and tools; [4] the location of the work; [5] the duration of the relationship between the parties; [6] whether the hiring party has the right to assign additional projects to the hired party; [7] the extent of the hired party’s discretion over when and how long to work; [8] the method of payment; [9] the hired party’s role in hiring and paying assistants; [10] whether the work is part of the regular business of the hiring party; [11] whether the hiring party is in business; [12] the provision of employee benefits; [13] and the tax treatment of the hired party.”) (citations omitted).

[20] Id. at 752 (citing Ward v. Atl. Coast Line R.R., 362 US 396, 400 (1960); Hilton Int’l Co. v. NLRB, 690 F.2d 318, 321 (2d Cir. 1982)).

[21] Aymes v. Bonelli, 980 F.2d 857, 861 (2d Cir. 1992) (“Some factors, therefore, will often have little or no significance in determining whether a party is an independent contractor or an employee. In contrast, there are some factors that will be significant in virtually every situation. These include: (1) the hiring party’s right to control the manner and means of creation; (2) the skill required; (3) the provision of employee benefits; (4) the tax treatment of the hired party; and (5) whether the hiring party has the right to assign additional projects to the hired party.”).

[22] Id. (“These factors will almost always be relevant and should be given more weight in the analysis, because they will usually be highly probative of the true nature of the employment relationship.”).

[23] Under the Copyright Act of 1976, copyright vests “initially in the author or authors of the work,” 17 U.S.C. § 201(a) (2006). As “the employer or other person for whom the work was prepared is considered the author” when a work made for hire is involved, however, a work made for hire initially invests in the employer or commissioning party. Id. § 201(b).

[24] See Patent Act of 1952, 35 U.S.C. § 131 (2006).

[25] See Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. § 102(a) (2006).

[26] See id. § 204(a).

[27] As described above, even works that are not created within the scope of an employee’s employment may be considered works made for hire. See supra note 17. However, works that are specially ordered or commissioned and considered works made for hire under Subsection 2 are outside the scope of this article.

[28] For example, in 2009, the founders of Skype, after selling the company to eBay, sued their former company and eBay for copyright infringement because, although eBay had purchased the good will in Skype, they had only licensed the source code to the program. See Complaint, Joltid Ltd. v. Skype Techs. S.A., 2009 WL 2958651 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 16, 2009) (No. 09 Civ. 4299); see also Brad Stone, Skype Founders File Copyright Suit Against eBay, N.Y. Times, Sept. 17, 2009, at B3, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/17/technology/

companies/17skype.html.

[29] See 17 U.S.C. § 408(a) (2006) (“[T]he owner of copyright or of any exclusive right in the work may obtain registration of the copyright claim . . . .”); id. at § 409 (“The application for copyright registration . . . shall include — (1) the name and address of the copyright claimant . . . (4) in the case of a work made for hire, a statement to this effect . . . .”).

[30] See id. § 411(a).

[31] See id. § 412.

[32] See id. § 106.

[33] See id. § 201(d).

[34] Id.

[35] Section 106A grants certain rights to “the author of a work of visual art,” See id. § 106A(a). However, section 101 defines a “work of visual art” as not including “any work made for hire,” Id. at § 101. In addition, in Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., the Supreme Court held that trademark law cannot be used to require attribution “to the author of any idea, concept, or communication embodied in [tangible] goods,” 539 U.S. 23, 37 (2003).

[36] See 17 U.S.C. § 203(a) (stating that exclusive or nonexclusive transfers or licenses of copyrights to works created on or after January 1, 1978 and not works made for hire may be terminated); id. § 304(c) (noting that exclusive or nonexclusive transfers or licenses of the renewal copyrights to works within its first or renewal term on January 1, 1978 and not works made for hire may be terminated).

[37] Id. § 203; see Simmons, supra note 17, at 274–75 (describing cases of termination involving comic book talent); cf. James Grimmelmann, The Worst Part of Copyright: Termination of Transfers, The Laboratorium (Feb. 15, 2012, 10:23 AM), http://laboratorium.net/archive/2012/

02/15/the_worst_part_of_copyright_termination_of_transfe (arguing that the inalienability created by the termination transfer provisions of the Copyright Act is unsupported by moral intuitions or logic).

[38] 17 U.S.C. § 302(a). A potential infringer may seek a certified report from the Copyright Office after 95 years for a published work or 120 years for an unpublished work. If the certified report does not disclose that the author of a work is alive or died less than 70 years prior to the report, the infringer is entitled to a presumption that shields her from infringement liability. Id. § 302(e).

[39] Id. § 302(c).

[40] On the other hand, a long-lived author could result in a significantly longer period of protection.

[41] By avoiding negotiation, parties also avoid the possibility that a court would interpret contract terms later in a way that the original parties to the agreement would not have anticipated. See, e.g., Marvel Characters, Inc. v. Simon, 310 F.3d 280 (2d Cir. 2002) (holding that although both parties had signed a settlement agreement stipulating that a work was made for hire, the provision was ineffective because it was signed subsequent to the work’s creation with purported retroactive effect).

[42] An additional societal benefit might include the idea that the work made for hire doctrine may permit and even incentivize the creation of works that would be impossible to create if the employing company had to negotiate with each employed author.

[43] Patent Act of 1952, 35 U.S.C. § 154(a)(2) (2006) (“[S]uch grant shall be for a term beginning on the date on which the patent issues and ending 20 years from the date on which the application for the patent was filed in the United States . . . .”). The Patent Act contains provisions providing for extensions to the patent term in certain circumstances. See id. § 154(b) (describing patent term adjustment for PTO delays); id. § 155 (describing patent term extension for Food and Drug Administration approval); id. § 156 (describing patent term extensions for other regulatory review).

[44] See id. § 261 (“Applications for patent, patents, or any interest therein, shall be assignable in law by an instrument in writing. The applicant, patentee, or his assigns or legal representatives may in like manner grant and convey an exclusive right under his application for patent, or patents, to the whole or any specified part of the United States.”).

[45] Kurtzon v. Sterling Indus., Inc., 228 F. Supp. 696, 697 (E.D. Pa. 1964) (“[A] ‘shop right’ or license to use, manufacture and sell.”).