By Dr. Thibault Schrepel*

Download a PDF version of this article here

Introduction

“To evaluate is to create.

Hear this, you creators!”

– Friedrich Nietzsche

This paper originates from a long-standing anachronism of antitrust law with regard to high-tech markets. Conventional wisdom assumes that antitrust law mechanisms are well suited to the study of practices in technology markets and that only adjustments

should be made to these mechanisms, and sparingly at that.[2] This is untrue. Several practices fall outside the scope of antitrust law because the mechanisms for assessing the legality of practices are not adequate. In fact, no one can accurately identify a typical legal approach for non-price strategies, a truth which gives way for a chaotic jurisprudence to emerge from this lack of universal understanding, which we will show.[3]

This article further aims to contribute to the literature by advancing a new test, the “enhanced no economic sense” (“ENES”) test, to be applied to non-price strategies.[4] We show why applying it with consistency will help to simplify the law while avoiding legal errors – two goals that all of the tests aiming to assess the legality of practices under antitrust law should reach.[5] Some of these tests, which are too permissive, generate many type-II errors but are easily understandable, and thus, increase legal certainty. Others, which are better suited and, in theory, allow avoidance of legal errors, are too complex to be applied by the courts and, above all, to be understood by laymen.[6] But one must not give up. Antitrust law is not condemned to remain blind to certain technical problems or, on the contrary, to be incomprehensible to the ordinary man. The “ENES” test brings a solution of reason to this long-standing issue.

We should not adopt a new test without first ensuring that it would allow courts and antitrust authorities to take a position in each individual case and that rulings would benefit consumers as a result.[7] Here again, the “enhanced no economic sense” test meets this double objective. It also helps to understand why several decisions made in the past are, we will argue, legal errors. The Microsoft case[8] is one of them.

In turn, this paper makes a proposal to rethink the way most of the new practices implemented in technology markets are actually evaluated. This study is particularly timely because the development of the issues related to these markets, and the growing interest shown by competition authorities[9] calls for an identified position; one which will not hinder their extraordinary growth.

This paper proceeds in three parts. The first part presents the “enhanced no economic sense” test, ranging from its foundations up to detail of its implementation. The second part probes the test’s empirical efficiency, exploring the most important predatory innovation cases on non-price strategy reassessing them through the prism of the “enhanced no economic sense” test, which helps to establish the test’s effectiveness. The last part expands these empirical findings and presents our conclusions.

I. THE IMPROVED VERSION OF THE “NO ECONOMIC SENSE” TEST

The “no economic sense”

test is best suited to assess non-price strategies—in other words, all those which are unrelated to pricing changes. It complies with most of the characteristics that a test should have—its mechanism is easily understood and most of its criticisms fall short. And yet, the test may be improved to create less type-II errors while retaining its best features. This section details, accordingly, how to design a new version of it.

A. How to Determine Which Test to Apply

Determining which test is best-suited to assess non-price strategies implies considering which goals are to be assigned to antitrust law, and, accordingly, which characteristics the ideal test should have.

1. Regarding the Goals of Antitrust Law

The choice of which test is the most suitable for analyzing non-price strategies involves considering several elements. The first element is related to the goals that must be assigned to antitrust law.[10] These objectives may be grouped into three theories:

1. The “efficiency theory”:[11] according to this theory, antitrust law’s primary goal is to increase economic efficiency. Type-I errors[12]

are seen as the greatest evil because they deter investments. Under this theory, there is no presumption of anti-competitive practices simply because a company holds a monopoly power.

2. The “consumer protection theory”:[13] this theory is based on the idea that the ultimate objective of antitrust law is to benefit consumers, not necessarily to increase economic efficiency. It contemplates criteria other than pure economic ones, such as preventing big mergers or overprotecting small businesses.[14]

3. The “growth-based theories”:[15] these related theories aim to enhance economic efficiency and prevent unwarranted transfers of consumers’ surplus. As a result, innovation is at the center of the debate, unlike theories which are only centered on economic efficiency and which do not necessarily involve the protection of innovation in and of itself.[16]

Most non-price strategies assume there are technological aspects directly related to innovative fields.[17]

Accordingly, while evaluating practices’ efficiencies, courts must take great care not to impair innovation. For that reason, choosing a test included in the growth-based theories is ideal. The “no economic sense” test evaluates the reason a company has implemented practices and also makes it possible to take innovation and technological breakthroughs into account.

2. In Terms of its Efficiency

The second key component to be studied in order to identify the most appropriate test to detect anti-competitive practices is efficiency.[18] It cautions against multiplying the situations in which the courts are unable to judge whether some practices must be condemned.[19] It also means avoiding type-I and II errors.

In its 2005 study entitled “Competition on the Merits,”[20] the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (“OECD”) identified six criteria for evaluating various tests’ efficiencies.[21]

The first relates to their accuracy: the tests must be based on accepted economic theories and, meanwhile, must avoid type-I and II errors. The second is linked to their administrability, understood as ease of applicability.[22] The third refers to their applicability: the tests should cover all of the issues raised by one type of anti-competitive practice. The fourth relates to their consistency, which should lead to homogeneous solutions.[23]

As underlined by one author, the tests applied to predatory innovation are plural.[24] This should be changed. The fifth emphasizes their objectivity. The sixth and final criterion is related to their transparency. The tests must aim at defending the goals that have been identified as being the most crucial to antitrust law, i.e. the growth-based theories. The ENES test will meet these criteria, as explained below.

B. On Why the “No Economic Sense” Test Is Suitable

1. Its Main Characteristics

The “no economic sense” test is based on the simple idea that a practice should be regarded as anti-competitive if it makes sense from an economic point of view only because of its tendency to eliminate or to restrict competition.[25]

While this test is often presented as being close to the “profit sacrifice” test,[26] the fact of the matter is that it differs greatly from it. For instance, when applying the “no economic sense” test, a practice may be sanctioned if it makes no sense—besides creating anti-competitive effects—even though it did not involve any losses for the company.[27] At the same time, a practice that involves losses may still be seen as being pro-competitive if it is justified by potential gains in economic efficiency.[28] To the contrary, the profit sacrifice test condemns all practices that involve significant short-term sacrifices.[29] In short, the “no economic sense” test raises the question of why

the defendant agreed to bear losses, which the profit-sacrifice test does not.

Gregory J. Werden, one of the “no economic sense” test’s greatest defenders, also underlined that, according to this test, practices are seen as being anti-competitive when, in addition of having no objectives other than eliminating or restricting competition, they also have the potential effect of restricting competition.[30] Establishing whether the practices have the potential to eliminate the competition is then a prerequisite,[31] and the burden of proof lies on the complainant.[32]

Also, the “no economic sense” test does not imply an ex-post evaluation of a practice’s effects. Rather the court’s duty is to evaluate the practice by taking into account all of the elements available to the dominant firm at the time of its implementation.[33] A practice may have been extremely profitable for reasons that were not anticipated by the company and this should not lead to a finding that the practice is pro-competitive. Also, as Werden notes,[34] a practice may have anti-competitive effects that were unpredictable at the time of its implementation and it should not be used as a means of late condemnation.

In fact, not evaluating the ex-post effects produced by a practice and not focusing on its costs are the reasons why the “no economic sense” test—even though it may be used to address non-price and price strategies[35]—is even more efficient for practices involving low costs, which is an important difference from the profit sacrifice test. It is then particularly suitable for evaluating predatory innovation, which is why it has led many jurisdictions to apply it in related cases.[36]

Another test called the “sham test” could also be suitable because its grounds are similar to the “no economic sense” test.[37] If we consider that innovation is an economic justification in itself, then, applying the “no economic sense” test asks whether the “innovation” is genuine or a “sham.”[38] An “innovation” will be considered a “sham” if it exists only for its negative effects on competition.[39] In other words, the definition of a “sham innovation” is any product modification that does not improve the consumer’s well-being in the short or the long term. The similarity of the two tests is particularly enlightening on the definition to be given for predatory innovation. In assessing whether innovation is real,[40] these two tests stand as opposing the vision of pioneer scholars Janusz

Ordover & Robert Willig: that even genuine innovations can be anti-competitive.[41]

In short, unlike several other tests, which lead to a finding of anti-competitiveness in genuine innovations that improve the consumer welfare whenever anti-competitive effects are significant,[42] the “sham” and the “no economic sense” tests do not. The reason why the “no economic sense” test is preferable to the sham test is because it also encompasses non-price strategies that are not directly linked to products’ modifications, like those related to “low-cost exclusion” as a “refusal to deal”.[43] Further, its terminology is self-explanatory to the extent that the terms indicate its analysis mechanism, which can only increase legal certainty.

All of these reasons led to the application of the “no economic sense” test in the US courts[44] in Aspen Skiing,[45] Matsushita Industrial Co., Ltd. v. Zenith Radio Corp. and Brooke Group,[46] and US v. AMR Corp.[47] The Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission also argued for applying it in Trinko.[48] Instead, the Court applied the profit sacrifice test, without naming it, by deciding that the dominant company aimed to sacrifice short-term profits in order to compensate for long term ones.[49] Accordingly, criticisms of that decision are irrelevant to the “no economic sense” test.

European courts have also applied the test on several occasions, although they rarely use the exact terms to describe it. For instance, the Court of Justice implemented it in British Airways[50] and the General Court of the European Union did the same in UFEX[51] and Telefónica, referring to practices as “irrational from an economic point of view.”[52] The test was also applied by national competition authorities in France in British Airways v. Eurostar.[53]

2. Inoperative Criticisms

As we have shown, when dealing with predatory innovation, the “no economic sense” test is the best alternative. For that reason, Herbert Hovenkamp proposes applying it to all cases of this kind.[54] The vast majority of criticisms raised against it fall short.

As for consumer protection. Some have denounced all tests based on analyzing predatory innovation’s effects on the company that implemented it in any given instance.[55] They argue that antitrust law is about addressing the direct effect of practices on consumers[56] and that the “no economic sense” test does not protect consumer welfare.[57] But this criticism is based on false premises. Assessing whether a practice makes economic sense for reasons other than its anti-competitive aspects is the same as protecting consumer welfare because factors favoring consumer welfare align with economically sensible reasons for modifying an existing product. In fact, only two situations exist under the “no economic sense” test:

1. If the practice does not pass the test and thus is deemed to be unlawful, the damage to the consumer is certain since the anti-competitive effects of the practice have driven its implementation;

2. If the practice passes the test and is thus considered to be lawful, it may be:

a. entirely pro-competitive, a situation in which the consumer welfare is necessarily increased;

b. pro and anti-competitive at the same time (the practice is “hybrid”), but the practice is deemed legal as a whole in order not to discourage investments that ultimately benefit the consumer. There is a real danger in micro-analyzing innovation, practice by practice,[58] and applying this test avoids this pitfall to the extent that when practices are considered together a practice may be justified by the presence of another practice that is linked to it.

As for type-II errors.[59] One of the strongest criticisms[60] made to the “no economic sense” test is the courts’ supposed inability to evaluate hybrid practices that produce both positive and negative effects on competition.[61] Situations where a practice is economically justified but also involve anti-competitive features are indeed problematic. Predatory innovation is a good example of this; it would be easy for a company to modify one of its products in a small, pro-competitive way, while also implementing a very effective anti-competitive strategy. In fact, creating an analytical framework for this type of situation is the raison d’être of the “no economic sense” test.[62] This test seeks to avoid balancing the positive and negative effects to the extent that such a process is expensive and uncertain. The ENES test allows for some type-II errors rather than engendering type-I errors that discourage innovation.[63] In short, the “no economic sense” test prefers a result with type-II errors[64] to the possibility of implementing a more intricate test without consistency and accuracy.[65]

As for its simplistic features. Several authors have stressed[66] that some practices could be anti-competitive while being justified from an economic standpoint. This may be the case, for instance, when a company decides not to reveal the existence of several of its patents during a standardization process.[67] In such a case, the firm is implementing an anti-competitive practice although it is economically justified by the fact that it won’t necessitate providing extensive information about its patent—which may be a long and expensive process. In essence, the idea is that the “no economic sense” test is too Manichean,[68] and that a dichotomy between practices that are economically justified and practices that are not is far too removed from economic reality to hold true.[69]

Once again, this criticism seems to disregard the very foundations of the “no economic sense” test. The latter does not advocate for penalizing all practices that do not make economic sense, but only does for those that do not make economic sense without anti-competitive reasons behind them.[70] The example in which a company refuses to provide information to standard organizations is then covered.[71] In fact, let us ask the following question: why condemn the implementation of a practice that a company can justify? Antitrust law is not about imposing on all companies to have an overview of the markets on which they operate. Whenever they can justify a practice, it should be authorized, irrespective of its effects on competition.

As for its manageability. Some have pointed out that the “no economic sense” test was inapplicable when predatory practices involved low costs.[72] This statement is incorrect, however, to the extent that this test condemns practices that exclude competitors, regardless of the costs incurred.[73] Similarly, the criticism related to the inability to implement the test in situations where a company would have mixed intentions must be rejected since this test is indifferent to the subjective intention of the company.[74] One may think, finally, that the test is unsuitable for disruptive innovations in which development makes “no economic sense” because they are, for example, driven by an extravagant philanthropist’s irrational desire. But the “no economic sense” test does not lead to condemning such innovations either if they do not have solely anti-competitive consequences.[75]

As for giving leeway to the judge. The “no economic sense” test is said to create “safe harbors”[76] which would deprive judges of their utility. In this way, the application of the “no economic sense” test could be contravening the spirit of the rule of reason because it would create per se legalities. In reality, applying the “no economic sense” test does not remove the judge from the decision-making process. The judge remains in charge of deciding, according to the law, what constitutes a valid economic justification.[77] Such a role is particularly important as it gives legitimacy to the test as a whole.

As for subjective intent. A distinction should be made between objective and subjective intent. The first—objective intent—is the result of hard evidence, for instance, emails in which the company’s CEO has confirmed his intention to modify a product for the sole purpose of reducing competition.[78] The second one—subjective intent—implies inferring executives’ intentions by analyzing the facts. Some European authors argue for taking subjective intention into account[79] and the Chicago School’s scholars have also done so by stressing that the intention is important[80] when evidence of anti-competitive harm cannot be provided by other means.[81] Courts could adopt three different approaches:[82]

1. not taking subjective intent into account;

2. taking subjective intent into account only when it is proved to be useful and without asking for the anti-competitive intent to be shown in order to condemn a practice;

3. taking subjective intent into account so to establish a violation of antitrust law.

In fact, taking subjective intent into account is championed by Phillip Areeda & Herbert Hovenkamp.[83] Courts have taken subjective intent into account in the C.R. Bard v. M3 Systems[84] case. It was also the position adopted in the Microsoft

case.[85] Other cases have followed since then.[86] In fact, several of the tests assessing the legality of unilateral practices take subjective intent into account. The “no economic sense” test does not, which is fortunate for our purposes.[87] In our review, only hard facts and empirical data should be used to establish practices’ illegality. In fact, taking a company’s subjective intent into account is far too unpredictable because it requires frameless control by the judge. Antitrust law is about pursuing economic efficiency. It should lead to imposing penalties only when the evidence of damage is indisputable.[88] Also, because innovation is inherently predatory,[89] taking subjective intention into account makes little sense.

Accordingly, some of the European and North American doctrine on this topic opposes the inclusion of subjective intent.[90] Frank H. Easterbrook, for instance, particularly highlighted the fact that analyzing intention did not allow one to distinguish between true monopolization and attempts to monopolize.[91] He stressed that evaluating a company’s subjective intention was expensive and had the effect of reducing legal certainty.[92] Further, distinguishing anti-competitive intent from pro-competitive intent may be more difficult than it seems. The language used between business executives may wrongly imply an anti-competitive intention. Considering subjective intention could be particularly harmful for small businesses where the language used by the staff may be more explicit than it is in larger corporations where executives are more sensitized to antitrust rules.

As for behavioral economics. Some authors[93] advocate for incorporating “behavioral economics” according to which agents sometimes show a bounded rationality.[94] But the “no economic sense” test wisely rejects any consideration of behavioral economics.[95] No one would argue that agents are rational in every situation, and further, behavioral economics lacks empirical evidence to be integrated into the decision-making process.[96] Studies of behavioral economics fail, to the best of our knowledge, to reveal consistent trends that might be integrated into the rule of law.[97] It must therefore be set aside—as least for ex ante

purposes—until it becomes more sophisticated.

As for its long-run effects. Professor Salop highlighted that the “no economic sense” test could lead to legalizing practices that provide an immediate benefit to consumers, such as improving a product, but eliminate competition over the long term, for instance, by removing product compatibility.[98] This would have the effect of increasing prices and thus harming consumers.[99] Such an example, however, assumes that the dominant firm is willing to reduce the usefulness, and therefore the value, of its product by removing its compatibility with other products. This hypothesis also presumes that the company enjoys an absolute monopoly power, because, otherwise, it would be safe to say that competition would actually push it towards compatibility with the aim of creating a network effect.[100] Plus, in the absence of a monopoly power, eliminating compatibility could lead consumers to adopt competing products.[101]

This hypothesis assumes, furthermore, that the dominant firm is present on both the upstream market, concerned by the changes, and a downstream market, where compatible products are. If this is not the case, removing compatibility would be illogical.[102] The example presumes, also, that the market conditions will stay unchanged. It also excludes dynamic efficiency considerations. Indeed, it is required for the dominant firm to know that its market shares will remain at a constant level, otherwise, it may not recoup its losses.[103] With high-tech markets, where market shares are evolving very quickly, it seems unlikely that companies would take such a risk. Disruptive technologies appear abruptly and create new markets, which very often eliminate all possibilities for “locking” the consumer into a market that no longer exists.[104] This example presumes, lastly, that it is better for consumers to have compatible products of lower quality than incompatible products with a higher quality. These different assumptions put together tend to prove the ineffectiveness of this criticism.

As for empirical evidence. Part of the scholarship on this topic notes that the “no economic sense” test excludes empirical evidence on the effects of practices.[105] It seems, conversely, that it allows a fair balance between legal certainty, on the one hand, and the need to consider empirical evidence in order to improve the analysis on the other.[106] If new empirical evidence shows that a practice, previously legal, is in fact having anti-competitive effects, the “no economic sense” test will lead to condemn it. The contrary is true as well. A practice seen as illegal for years may become permissible if new economic evidence is adduced by the company.

C. How to Improve the “No Economic Sense” Test

We have shown that the “no economic sense” test is particularly efficient for analyzing non-price strategies such as predatory innovation. And yet, as explained, applying the test as it was originally designed implies a trade-off: creating some type-II errors in exchange for legal certainty. Although this could be defended, this article intends to demonstrate how this trade-off may be avoided by applying an improved version of the “no economic sense” test, which would maintain legal certainty while avoiding any type of legal errors.

The “no economic sense” test might be improved, but it is important not to create a new version that would have high implementation costs. While keeping this objective in mind, we propose an “enhanced version of the ‘no economic sense’ test,” which answers criticisms related to the underinclusivity of the test and potential difficulties with applying the test when pro and anti-competitive modifications coexist.[107] Two situations may thus be distinguished, one in which product changes are separable from one another and one in which the changes cannot be isolated.

When the changes may be separated from each other. Unlike innovations in the traditional sectors of the economy, innovations developed in high-tech markets often have the advantage of being readable[108] to the extent that it is possible to analyze each line of the source code.[109] Whether innovations introduced in high-tech sectors intend to create a new software structure, to add new features to a product, to facilitate product use, or to increase its security, most of these objectives are achieved by the means of one or more lines of code.[110] The purpose of each of these lines is clearly identifiable.[111]

The software (or product) as a whole is thus distinguished from each of the features that can be adjusted individually.[112] It may also be distinguishable from its updates if the introduction of new software always benefits to the consumer,[113] some of its updates may play against its interest. Accordingly, some authors have raised[114] the point that predatory innovation is more easily identifiable on high-tech markets than others.[115]

Consequently, the “no economic sense” test may be improved by identifying the purpose of every update of a product, and more specifically, each element of the update. Litigious situations where pro and anti-competitive effects are recorded simultaneously tend to disappear to the extent that each of these effects may be separated from the others. As a result, applying the “no economic sense” test is even more relevant. It is not for the judge to interfere with the company’s management and/or express disapproval with the strategic choices so to punish companies for not having implemented “less anti-competitive”[116] practices. Rather, the judge is tasked with punishing actors that implement practices that could have been implemented without harming the consumers’ well-being.

Applying the enhanced version of the “no economic sense” test will have the following structure: in the first instance, the complainant will have to establish the injury he suffered, and in response, the defendant will try to justify each of the changes made to the product. The judge will guarantee the proper conduct of this analysis and will identify all product modifications that have a solely anti-competitive effect. This role is crucial. Consider the situation where a company decides to eliminate its products’ compatibility with those of its competitors. Imagine that the dominant firm is justifying this change by showing that the new version of its product allows geo-location. In this example, the company has an economic justification—adding a new function to its product—but because it is unrelated to the removal of compatibility, doing so is anti-competitive and should be condemned. The judge then has the responsibility to reject all economic justifications made in bad faith. When doing so, he ensures that companies cannot escape liability, as they might under the traditional “no economic sense” test, by presenting “ghost” justifications[117] unrelated to their practices.

Rules for eligibility of evidence in these inquiries can be inspired from the Daubert

criteria,[118] which fit in line with the work of Karl Popper.[119] In its famous ruling, the Supreme Court held that pursuant to Rule 702 of the Federal Rules of Evidence governing expert testimony, only those using recognized “scientific method[s]” are to be taken into account. The court admitted the need to “filter” the scientific evidence produced in court. A similar filter should be implemented when applying the “no economic sense” test to invalid economic justifications, evidence or, expert reports that do not have a scientific value but have the sole purpose of obscuring the procedure.

When the changes are indivisible. Although the changes made to a technological product are generally separable from each other, that is not always the case. Let us imagine a situation in which a dominant firm decides to remove the compatibility of its products with the specific aim of increasing their safety. It would be possible to track what changes in the coding led to elimination of product compatibility. However, if the economic justification provided by the company—namely increasing products’ safety—is directly linked to the compatibility removal, the practice will be considered pro-competitive.[120] In this situation, a single line of code is added (or removed) to delete product compatibility, but it produces two consequences that cannot be separated. Imagine an alternative situation in which a company decides to increase the execution speed of its software by using Wi-Fi rather than Bluetooth. In addition, suppose that, for security purposes, all compatible devices use Bluetooth rather than Wi-Fi. Once again, the judge could easily track which lines of code have enabled the addition of new functionality, on the one hand, and the removal of product compatibility with Bluetooth on the other. Yet, the practice must be deemed pro-competitive because increasing the speed of the product is a valid economic justification caused by replacing the Bluetooth functionality. In this case, even though several lines of code are modified, they cannot be analyzed separately.

Accordingly, the judge must (1) ensure that only valid economic justifications are brought by the parties and (2) determine which modifications may be separated from each other.[121] These two steps are the keystones of a decision process free of judicial errors. This reasoning seeks to encourage investments in the short term and allow continued sophistication of antitrust law by better matching business justifications. In order words, it is about creating the smallest safe harbor possible—when practices cannot be separated—so that antitrust law is effective. It allows, at the same time, a drastic increase in the level of legal certainty by providing an understandable legal framework.

D. Modeling of the Proposed Test

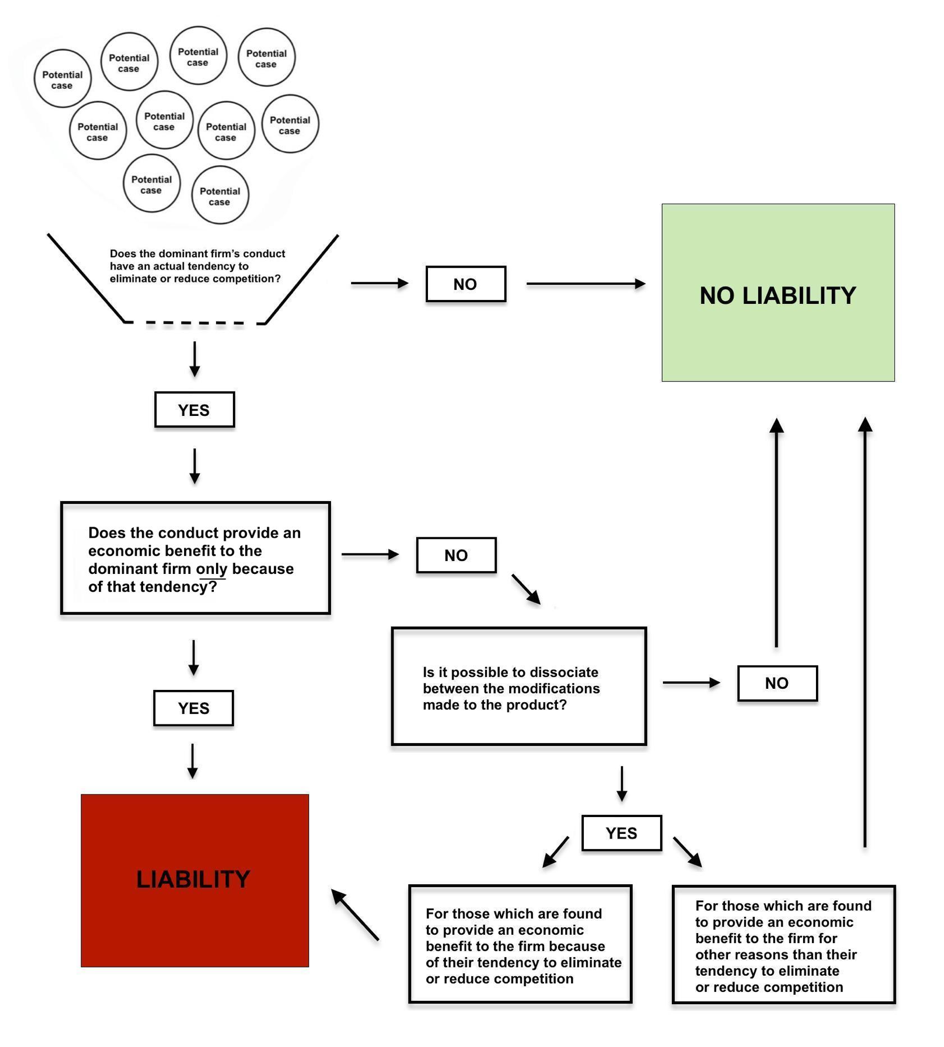

The enhanced version of the “no economic sense” test is comprised of four steps. Together, the steps ensure a legal analysis that detects predatory practices as precisely as possible.

Step 1: Does the practice implemented by the dominant company tend to reduce or eliminate competition? If the answer is negative, the practice is deemed to be legal. If the answer is positive, the analysis moves on the second step.

Step 2: Does the practice provide a benefit to the dominant firm solely because of its tendency to reduce or eliminate competition?[122] If the answer is positive, the practice must be condemned. If the answer is negative, the analysis moves on the third step.

Step 3: If the judge suspects that some of the effects created by the practice are pro and anti-competitive, he must determine whether it is possible to distinguish between the modifications made to the product and their economic justifications. If the answer is negative, the practice is deemed to be legal as a whole. If the answer is positive, the analysis moves on the last step.

Step 4: Modifications that make economic sense for reasons that are not anti-competitive must be allowed, while modifications that only tend to reduce or eliminate competition must be condemned. The penalties should be proportional to the intensity/number of anti-competitive practices.

This test, by avoiding judicial errors, ensures short-term efficiency by raising the level of legal certainty for companies while eliminating practices that, without any doubt, are predatory. Moreover, allowing courts to analyze practices related to product modifications will have long-term effect of improving their expertise. Finally, it must be noted that some practices deemed to be legal will be proved to be anti-competitive in a near future. The opposite is true as well.

This graphical representation summarizes the 4 steps detailed beforehand.[123]

II. APPLICATION TO MAJOR PREDATORY INNOVATION CASES

Now that the enhanced version of the “no economic sense” test has been explained, it will be applied to the major cases dealing with predatory innovation so as to demonstrate its efficiency. The same methodology is used for each case. We begin with a brief summary of the facts, then we explain the test applied by the court and the court’s decision.[124] We then apply the new test to the facts and discuss alternatives to the courts’ conclusions.[125]

A. The Berkey Photo v. Eastman Kodak case (1979)[126]

Facts. In the late 1960s, Kodak dominated the cameras and compatible products markets. In 1972, the company decided to introduce a new system, the “110 Instamatic,” as well as a new device, the “Kodacolor II film.” The new device was smaller and simpler to use than the previous ones. It was also incompatible with the products of one of its competitors in an ancillary market. Berkey brought suit against Kodak for having illegally removed the compatibility of its products.

The test applied by the court. The Second Circuit applied a “reasonableness” test[127] and centered its analysis on the fact that a single improvement could justify all modifications made to the product.

The solution. First, the Second Circuit held that an “innovation” may be prohibited by antitrust law if it is proved to be anti-competitive.[128] The court then noted that the new camera introduced by Kodak, the Kodacolor II film, had several lower quality features than its former model. In particular, the Court found that its autonomy was shorter[129] and that it generated more “red eye” in photos. The new device, however, had a better grain[130] and was smaller. The judges then held that comparing the features of the two devices was not a probative element given the different characteristics of the two, which were performing better in different areas.[131] The Court held that Kodak was not liable.[132]

Application of the enhanced version of “no economic sense” test. The Court’s holding justified a set of practices on the ground that one of them was pro-competitive.[133] But, as we have discussed, whenever it is possible to distinguish between the modifications made to a product and their justifications, the judge must condemn the anti-competitive ones. In the present case, Kodak—which initially asked for a per se legality to be applied—argued that the few improvements made to its product justified all the modifications, including those that may have anti-competitive aspects.[134] Berkey argued, on the contrary, that Kodak had introduced a less efficient camera for the sole reason that it would no longer be compatible with Berkey products, which justified holding them liable.[135] The Court found that even though some of the new features of the Kodacolor

II were inferior to those of Kodacolor X, they did not translate into anti-competitive strategies in themselves because they could have reduced the attractiveness of the new camera to consumers without directly affecting competition. Berkey’s argument based on the characteristics of the Kodacolor II film was accordingly deficient.[136] In addition, Berkey failed to prove that Kodak could have marketed a smaller camera while improving all characteristics of the earlier version. Nevertheless, one must ask whether removing the new camera compatibility with Berkey’s products was a necessity in order to achieve its goal. In the present case, because Kodak did not demonstrate the causal link between the new design of its device and the need to remove it, it arguably could have been held liable.

Applying the enhanced version of the “no economic sense” test would have resulted in a different outcome from the one found by the Second Circuit. Kodak could have been held liable for having removed the compatibility of its new camera—if it was an anti-competitive strategy, which the Court did not address. Legal certainty would have been enhanced by a court decision that provides clarity and predictability to all companies on the market, which would, in turn, minimize impeding innovation by a type-II error. Not to mention, it would have also benefited consumers.

B. The North American Microsoft case (2001)[137]

The approach adopted by European and North American courts regarding predatory innovation practices differ on several points. Notably, European judges extend the essential facilities doctrine to high-tech markets while North American courts refuse to do.[138] The Microsoft case illustrates this fundamental distinction. This case also remains one of the pillars of predatory innovation doctrine. It is, in fact, the first case in which a court studies software encoding in such detail.[139]

Facts. The Microsoft case was the subject of a long series of jurisprudence, which ended in June 2001 (with “Microsoft III”) with a decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.[140] One of the practices considered[141] was the way Microsoft integrated Internet Explorer into its operating system. In doing so, the company:

• deleted the function allowing one to remove the software from the operating system (practice n1);

• designed the operating system in order to override the user’s choice to use a different browser (practice n2);

• designed the operating system so that when certain files related to Internet Explorer were removed, bugs appeared (practice n3).

The plaintiffs stressed that Microsoft had set up several anti-competitive practices to eliminate Netscape, which was a browser that provided some basic functions similar to that of an operating system.[142] Moreover, the complainants denounced the fact that Microsoft had developed a Java script incompatible with Sun Microsystem’s products.[143]

The test applied by the court. This decision is one of the first related to high-tech markets to have considered the balancing test,[144] even though the court did not apply it. The burden of proof was initially on the plaintiff to demonstrate the anti-competitive effects of the practices.[145] The defendant then had to demonstrate that the pro-competitive effects prevail over anti-competitive ones.[146] In theory, if the defendant did so, the plaintiff then had to prove that the defendant was incorrect. This balancing theoretically ended once a party showed conclusively that the dominant effects were pro or anti-competitive. In the present case, even though the court was “very skeptical about claims that competition has been harmed by a dominant firm’s product design changes,”[147] it opined that applying a per se legality to such practices was inappropriate because they may have various effects on competition.[148]

The solution regarding Internet Explorer.[149] The Court held that practices n1 and n3 were illegal.[150] On the other hand, it found that the practice n2 was pro-competitive. The court ruled that the “technical reasons” provided by Microsoft were exculpatory considering that the plaintiffs failed to demonstrate a greater anti-competitive effect.[151] The Court also ruled that a company’s technical justifications may not be sufficient to establish the legality of a practice. This implies that a genuine technical innovation may be considered anti-competitive if it causes great damage to the competitive process. This reasoning was not applied in this case because the plaintiffs failed to demonstrate any anti-competitive effect,[152] but it did challenge the claim that antitrust law protects innovation.[153] The consequences in terms of disruptive innovation are particularly dangerous because they create a destructive effect on existing markets. In short, a sole pro-competitive effect was proven in practice n2, but only anti-competitive effects were argued for practices n1 and n3. As a consequence, the judges did not conduct a balancing of any of the effects[154] and the decision does not illustrate the practical application of the balancing test.[155]

The solution regarding Java. The plaintiffs also challenged the practices implemented by Microsoft in the development of Java for Windows. They complained, in particular, that Windows Java was incompatible with Sun Microsystems’ products.[156] Windows, in opposition, argued that its own Java should be allowed because of its superiority to Sun’s Java.[157] The Court found that a company’s dominant position does not prohibit it from developing products that are incompatible with those of its competitors,[158] and thus, the court justified Microsoft Java’s incompatibility with Sun because of its greater power and speed.[159]

Application of the enhanced version of “no economic sense” test. The Microsoft decision suffers from numerous flaws that would have been eliminated by applying the enhanced version of the “no economic sense” test.[160] According to the information available in the decision, Microsoft gave no pro-competitive justification for practices n1 and n3.[161] It is unclear whether Microsoft gave justifications that were rejected earlier in the procedure, but in the absence of any, these practices made sense solely because of their tendency to reduce or eliminate competition. A fine should have then been imposed.

Practice n2 was justified by Microsoft on the grounds that using Netscape’s browser prevented the use of the “ActiveX” which allowed the proper functioning of “Windows 98 Help” and “Windows Update.”[162] Microsoft also justified the forced use of Internet Explorer by explaining that when the user started Internet Explorer from “My Computer” or “Windows Explorer,” a different browser would not have enabled them to keep the same window.[163] Surprisingly, the court did not analyze the way Windows operated in more detail. Indeed, if it had been shown that the use of ActiveX was prevented when using another browser because of Microsoft’s anti-competitive desire, or, in other words, that Microsoft could have allowed Active X even with another browser, the company’s technical justification would have been nullified. Similarly, if it had been shown that another browser would have created the same ease of use with “My Computer” and “Windows Explorer,” the holding that only Internet Explorer could do it would have been refuted. In the absence of additional information, it is impossible to say whether the practice implemented by Microsoft was pro or anti-competitive. The lack of conviction in this case tends to minimize the poor reasoning led by judges, but a more detailed decision would have increased legal certainty, and ultimately would have promoted innovation.

Regarding the practices related to Java, the Court found that because Microsoft’s Java was more powerful than Sun’s, its design was de facto justified.[164] The dominance Microsoft enjoyed at the time did not create any duty to design compatible products with its competitors. It should be emphasized, however, that a different outcome would probably have been reached in the European system because of the principle of “special responsibility” for dominant firms. In any event, the application of the enhanced version of the “no economic sense” test would have resulted in an acquittal on behalf of practice n2. The application of that test would have also increased legal certainty by providing businesses a more comprehensive grid of analysis than the enigmatic one given by the Court.

C. The European Microsoft Case (2004)[165]

The Microsoft case, along with the Google case,[166] remains to this day the most iconic case in terms of abuse of dominant position. In addition to its importance regarding penalties, it is the first decision in which the Commission found that network effects could be used to strengthen the barriers to entry in high-tech markets.[167] Unlike the North American decision, the European Commission did not analyze the way[168] Microsoft integrated its software (here a media player) into its operating system. The North American judges condemned the company because the integration of Internet Explorer came along with micro-practices possessing anti-competitive effects that were distinguishable from the integration. The European decision, in contrast, disputed the integration of Windows Media Player in itself.[169]

Facts. On December 10, 1998, Sun filed a complaint against Microsoft on the grounds that Microsoft had refused to provide information allowing for the interoperability of Sun’s products with Microsoft’s PC.[170] In February 2000, the European Commission launched an investigation against Microsoft.[171] A second statement of objections against Microsoft involved interoperability and the integration of Windows Media Player within its operating system.[172] And yet another statement of objections was sent to Microsoft in 2003 following a market survey.[173]

The test applied by the court. Above all else, it should be underscored that the European Commission rejected Microsoft’s argument that antitrust law could not be applied to the New Economy.[174] The Commission pointed out that

“the specific characteristics of the market in question (for example, network effects and the applications barrier to entry) would rather suggest that there is an increased likelihood of positions of entrenched market power, compared to certain ‘traditional industries’,” and required a strict application of antitrust law.[175]

In fact, the European Commission seemed to apply a similar test to the one used by the North American Federal Court, but it is difficult to say if the Commission applied a “balancing” or a “disproportionality” test[176] given that the term “proportionality” does not appear in the decision.[177] But the similarities stop here. The North American and European procedures did not use the same semantic field[178] and practically showed a will to reach different outcomes. The European Commission multiplied the references to “the prejudice of consumers,”[179] “network effects,”[180] and “interoperability,”[181] while the Department of Justice reported the “predatory”[182] nature of the practices and the need to protect “innovation.”[183] The European Commission indirectly intended to ensure consumer protection by enabling products interoperability while the Department of Justice developed a broader view through a defense of innovation that aimed not to create type-I errors.[184] Most of the European Commission’s decision is devoted to the rules of “tying,”[185] which highlights the amalgam between this notion and the one of predatory innovation.[186] It also shows why “tying” does not cover all of the issues related to predatory innovation.[187] The Commission found that Microsoft had not put forward any efficiency gain that would justify the integration of its Windows Media Player into the operating system.[188] It held, however, that anti-competitive effects may have outweighed efficiency, at least in theory.[189]

The solution. The European Commission sanctioned Microsoft for numerous antitrust violations, which were confirmed by the General Court.[190] In analyzing Microsoft’s integration of the Windows Media Player (“WMP”) into its operating system, the Commission began by observing that there were no technical means to uninstall the player.[191] This observation led the Commission to analyze whether the interdependence of Windows Media Player with the operating system was necessary, thereby avoiding one of the main pitfalls of the American decision.[192] Microsoft replied, “if WMP were removed, other parts of the operating system and third party products that rely on WMP would not function properly, or at all.”[193] Here, Microsoft intended to prove the absence of predatory innovation, which deserved to be discussed. Unfortunately, the European Commission did not answer the argument.

In fact, the European Commission did not seem to address this issue because it was described under the broader label of tying. Instead of addressing the issue, the judges were almost exclusively concerned by the fact that Microsoft did not market a version of Windows without Windows Media Player.[194] But the practice in question concerned the functionality of the operating system. And the notion of tying was unfit to be applied because there was a technical reason to combine the products into one.[195]

Here lies one major criticism[196] one can make regarding European Commission decision: by refusing to analyze the issue of predatory innovation, the Commission deprived its decision of a legal basis for examining all of the anti-competitive effects identified by the complainant. The European Commission also noted that “it can be left open whether it would have been possible to follow Microsoft’s above line of argumentation had Microsoft demonstrated that tying of WMP was an indispensable condition for simplifying the work of applications developers.”[197] It was added that “Microsoft has failed to supply evidence that tying of WMP is indispensable for the alleged pro-competitive effects to come into effect,”[198] thus concluding that it was “technically possible for Microsoft to have Windows handle the absence of multimedia capabilities caused by code removal (and the resulting effect on any interdependencies) in a way that does not lead to the breakdown of operating system functionality.”[199] In this respect, the Commission held that Microsoft had not provided tangible evidence to support their argument that the integration of Windows Media Player simplified the work of application designers.[200] Conversely, the Commission did not underline a discussion regarding whether the integration of Windows Media Player to the operating system had allowed a more complete experience of Windows. Nevertheless, it concluded “it is appropriate to differentiate between technical dependencies which would by definition lead to the non-functioning of the operating system and functional dependencies which can be dealt with ‘gracefully.’”[201] In other words, Microsoft could have kept the other functions of the operating system but all functions directly or indirectly related to the use of such a player would have been inoperable without it or another player.[202] The distinction between technical and functional interoperability held by the European Commission is, in fact, essential. It indicates a difference between the interoperability necessary to the functioning of a product on the one hand and allowing a new feature to work properly on the other.

The Commission imposed a €497 million fine on Microsoft for its practices.[203] In a press release related to the United States’ investigation of the same matter, the Department of Justice called the sizable fine regrettable, especially because unilateral competitive conduct is “the most ambiguous and controversial area of antitrust” law.[204] The Commission also required Microsoft to sell a version of its operating system free of its Windows Media Player.[205] Lastly, the Commission ordered the company to disclose information that it had refused to previously provide for the development of products compatible with its own.[206]

Application of the enhanced version of “no economic sense” test. To the extent that the integration of Windows Media Player had strong pro-competitive effects—such as providing cost and time savings to consumers—applying the proposed test would have necessarily led to not condemning Microsoft. The Microsoft decision is therefore a type-I error. It would have been helpful for the Commission to analyze the anti-competitive aspects separate from pro-competitive aspects, but the Commission did not, demonstrating how European courts and authorities deal improperly with predatory innovation.[207] Analyzed correctly, the enhanced version of the “no economic sense” test shows that it was not possible to dissociate the integration of Windows Media Player from enhanced consumer well-being. Forcing the consumer to download another media player carried a direct injury to the consumer in itself. Further, Windows Media Player was not exclusive. In other words, the integration of WMP made economic sense to Microsoft not only because of the potential anti-competitive effects, but also because it improved the user experience. Accordingly, the European Commission made a critical error by holding a real innovation anti-competitive. The fact is that it is not for judges to order functions’ removal if they benefit consumers. In such a world, the door is open for competition authorities to prevent all innovations producing a low anti-competitive effect despite having great pro-competitive effects.

D. The iPod iTunes Litigation

The iPod iTunes Litigation is the most recent case to have drawn a great deal of attention to a practice of predatory innovation. It is particularly important because it took place several years after the Microsoft

and Intel cases, both of which had been influential for analyzing practices in the high-tech sector.[208] Yet, to the best of our knowledge, the iPod iTunes Litigation has never been examined closely.

Facts. On November 10, 2001, Apple introduced its portable music player, called the iPod.[209] One of its competitors, RealNetworks, analyzed the iPod’s software and managed to extract the code created by Apple for listening to downloaded files on the iPod. RealNetworks inserted this code in all MP3s sold in the RealNetworks Music Store. In 2001, Apple introduced iTunes, free software allowing users to manage audio files on the iPod. On April 28, 2003, Apple also introduced the iTunes Music Store (“iTMS”), an online store enabling direct music purchase.[210] Apple managed to modify the format of the regular audio files purchased on the iTMS by introducing a digital rights management (“DRM”) to restrict the use of regular AAC (“Advanced Audio Coding”) files.[211] This format was referred as “AAC Protected” and iTunes used a feature called FairPlay, which allowed Apple to manage this DRM. Apple also changed the iPod internal software so as to allow the proper reading of these “AAC Protected” files.[212] In July 2004, RealNetworks introduced the new version of its RealPlayer. It included a feature called Harmony that sought to imitate FairPlay

compatibility and enable audio files purchased from the RealNetworks

online store to be played on the iPod. In October 2014, Apple decided to release the version 4.7 of iTunes.[213] This version changed the FairPlay encryption method, removing any compatibility between Harmony and iTunes.[214] RealNetworks then restored this compatibility.[215]

A first complaint was introduced on January 3, 2005, denouncing the anti-competitive strategy implemented by Apple in order to eliminate competition on the online market for selling music.[216] On February 28, 2005, the plaintiffs also denounced the modification made by Apple of a free audio format, the AAC, into a protected audio format, the “AAC Protected.” They underlined Apple’s intention to exclude competitors from the market through an anti-competitive strategy[217]—predatory innovation. The applicants pointed out that the audio files purchased from the iTMS became incompatible with other audio players. Also, any files purchased from a store other than iTMS

became incompatible with the iPod. Lastly, the complainants alleged that Apple was unlawfully tying by requiring the purchase of an iPod in order to listen to the files bought on the iTMS and by forcing users to purchase songs on the iTMS in order to be able to use the iPod.[218] On March 7, 2005, Apple responded to the complaint pointing out, in the company’s opinion, the inaccuracy of the complainants’ allegations.[219] Apple stressed that listening to the files bought on the iTMS

using other music players remained possible by “burning” them into a CD-ROM and then by extracting the files from the CD on a computer to delete the protection.[220] As for tying, Apple underlined that a practice may not be condemned as such if, by buying the two products separately, it would be so expensive that no consumer would do so.[221] In September 2006, Apple released version 7.0 of iTunes, which, aside from introducing new features, once again deleted iTunes’ compatibility with Harmony.[222]

The test applied by the court regarding iTunes 4.7. Following a long process, the United States District Court for the Northern District of California was in charge of determining the legality of iTunes 4.7. Quoting Allied v. Tyco, the judges pointed out that the District Court has ruled that “there is not a per se rule barring Section 2 liability on patented product innovation.”[223] They also held that balancing the pro and anti-competitive effects of a new product was rejected in Allied.[224] The judges applied the same reasoning, holding that when a real improvement is shown, antitrust law should not condemn the modification.[225]

The solution found by the court regarding iTunes 4.7. Apple argued that the introduction of this new version of iTunes was motivated by the necessity to improve its security through the strengthening of anti-piracy protections.[226] Apple stressed, in particular, that (1) the earlier version of the software had previously been pirated, (2) that the proliferation of computer attacks that occurred at the beginning of 2004 led some music labels to require Apple to take corrective action, and, (3) that they changed the encryption method in accordance with the contractual provisions sent by music labels.[227] RealNetworks

underlined that Apple’s true intention was to remove the compatibility with the audio files purchased from its online store.[228] RealNetworks also stressed that Apple began developing a new FairPlay a month after it refused to grant RealNetworks a license, proving Apple’s anti-competitive intention. RealNetworks said it had concluded numerous deals with music labels, which threatened Apple’s position on the market for selling online music.[229] The company also emphasized how it had increased its market shares after launching Harmony, whereas Apple’s market share had, for the first time, dropped below 70%.[230] RealNetworks lastly argued that Apple showed its anti-competitive intention by threatening to remove any compatibility with Harmony.[231]

The Court ultimately rejected RealNetworks’ arguments. The court ruled that the introduction of iTunes 4.7 was a real improvement that could not be condemned. In particular, they emphasized that the expert appointed by RealNetworks reported himself that the new version of FairPlay was indeed harder to hack, significantly increasing its safety.[232] The court also underlined that no other practices implemented by Apple could have been challenged under antitrust law.[233] This precision is particularly interesting because it seems to recognize the possibility of dissociating the various technical changes made by Apple, on one side, and the pro-competitive modification related to FairPlay

security, on the other. But in fact, the Court merely analyzed whether Apple had breached antitrust law, without examining the technical aspects of the product in too much detail. This decision, thus, did not apply the enhanced version of the “no economic sense” test.

Application of the enhanced version of “no economic sense” test regarding iTunes 4.7. The court held that the practice implemented by Apple had the effect of reducing competition in the market for online music sales.[234] Yet, it is necessary to consider the possibility of distinguishing the improvement in terms of FairPlay’s safety from the eventual anti-competitive effects, namely, the removal of compatibility. Unfortunately, it is not possible to process this analysis as relevant expert testimonies are still covered by business confidentiality.[235] Accordingly, the merits of the decision adopted by the Northern District of California cannot be denied nor confirmed.

The litigation regarding iTunes 7.0[236] is of the same nature, though more complex. It occurred based on the fact that, in 2006, Apple introduced iTunes 7.0. Complainants highlighted similar problems to the 4.7 version.

The test applied by the court regarding iTunes 7.0. A jury was asked to evaluate the modifications made to iTunes 7.0.[237] The process that led to the question asked to the jury is to be analyzed carefully because its formulation significantly influenced the final outcome. Two points of disagreement arose between the parties. The first was related to the possibility of separating the practices from one another. The second concerned taking into account subjective intent, because even though the practices were seen as an indivisible whole, they could have been considered anti-competitive.

Regarding the modifications’ separability. In a November 18, 2014 document, which was jointly submitted by the two parties in order to define the legal issues, Apple’s counsel crystallized the case around the following questioning: was iTunes 7.0 a real improvement?[238] Apple’s counsel sought to apply the test set out in Allied Orthopedic, according to which if a product is improved, the modifications are deemed to be legal.[239] Accordingly, the new version of a product is either an improvement or a strategy seeking to eliminate competition.[240] The plaintiff noted that the way the question was formulated favored Apple.[241] They emphasized that evaluating whether the new version of iTunes included improvements was not sufficient.[242] They underlined, notably, that the changes made to the KeyBag

Verification Code (“KVC”) and the Database Verification Code (“DVC”) should have been brought to the jury’s attention as being independent practices.[243] Conversely, Apple argued for these amendments to be considered as a whole along with the iTunes 7.0 improvements.[244] And indeed, Apple stressed that according to Allied v. Tyco, all the changes were to be considered as an indivisible whole,[245] and that anyway, the practices could not have been differentiated in practice. Apple also gave two technical justifications for its actions: an increase in security, as well as strengthening against product corruption.[246] Unsurprisingly, in the hearing held on December 1, 2014, plaintiff’s counsel argued that they needed to ask the jury separately about the different product modifications.[247] The Court decided mentioning coding issues to the jury would be confusing.[248] All product modifications were then presented as an indivisible whole.[249] In this regard, it should be stressed that avoiding legal errors cannot be done when the essence of the issues are not submitted to the discretion of the courts and juries. Moreover, even by assuming that mentioning coding would have confused the jury, nothing actually prevented the court from analyzing the coding beforehand and then submitting an adapted question to the jury.

Regarding subjective intent. The plaintiffs stressed that according to Allied Orthopedic, a company that has improved its product but also voluntarily created substantial anti-competitive effects should be condemned.[250] They alleged that the improvements made on iTunes had anti-competitive purposes[251] and asked for the improvements to be balanced with the anti-competitive intent. They suggested that the jury follow a two-stage approach, analyzing whether the improvements were real, and if so, whether Apple had been driven by anti-competitive intent.[252] Apple stressed that the intention did not matter considering the fact that competition by innovation is about harming competitors by introducing a new product.[253] Apple claimed that, as long as some improvements to the product were shown, it could not have been sanctioned regardless of other considerations.[254] The judges took Apple’s side, stressing that product improvements were not to be balanced with anti-competitive intent. We subscribe to this analysis.

The solution found by the court regarding iTunes 7.0. The jury was asked the following question: “Were the firmware and software updates in iTunes 7.0, which were contained in stipulated models of iPods, genuine product improvements?”[255] and answered in the positive, saying that the update of iTunes 7.0 was a real improvement, and, therefore, pro-competitive.[256] Because of the question’s wording, the modifications made to the DVC and KVC codes were not properly analyzed.

Application of the enhanced version of the “No Economic Sense” Test regarding iTunes 7.0. Both claims made by the parties are supported by precedents.[257] In fact, the diversity of the tests chosen by the various jurisdictions throughout the years and the lack of standardization of these tests have had the effect of creating a very unclear jurisprudence, resulting in hard-to-understand litigation. On the merits, Apple’s argument, according to which all modifications were indistinguishable, is not convincing. The link between allowing videos to be played on iPods and the need to enhance security is not particularly obvious, but judging whether other changes[258] did necessitate eliminating compatibility should have been performed.[259] Unfortunately, such an analysis may not be conducted in great detail as the expert testimonies are still covered by business confidentiality.[260] Let us simply underline that not analyzing each modification separately raises the possibility that a type-II error was actually pronounced.

Unfortunately, the necessary information to conduct a deep analysis is not available.

CONCLUSION

This paper has examined the ENES test from a theoretical and empirical perspective. The main conclusion is that the test would improve the quality of the law for analyzing non-price strategies, which is greatly needed. More than a simple adjustment of the existing rules, it requires a new and standardized approach to these practices.

Conclusions drawn from the test cases. We have shown that the ENES test leans toward the conviction of practices that were deemed to be legal by the courts, like Berkey Photo v. Eastman Kodak. It also leads to exonerate Microsoft in the European case, contrary to what was done in the European Commission’s ruling. The same goes for CR Bard in its litigation. Lastly, applying this new test results in similar conclusions in four cases, the main difference being only that the ENES test would have greatly increased the level of legal certainty. A table in the appendix illustrates its effectiveness on a wider range of cases.

General contribution. We have demonstrated, in short, how the ENES test results in the creation of a uniform rule of law, which ultimately increases consumer welfare by encouraging companies to keep innovating. Consumer well-being is also improved by the elimination of anti-competitive strategies. As a matter of fact, the proposed test is easier to implement than most other tests, and yet, it limits legal errors more efficiently than others. Its quasi-mathematical aspect leads to a better understanding of the rule of law and it must, therefore, be implemented in all cases related to predatory innovation and other non-price strategies.

Appendix #1 – A reassessment of the major cases related to predatory innovation

| A reassessment of the major cases related to predatory innovation |

|||||

| Name & date of the case | IBM (1979) | Berkey Photo v. Eastman Kodak (1979) | CR Bard v. M3 Systems (1998) | United States v. Microsoft Corp US (2001) | European Commission v. Microsoft Corp EU (2004) |

| Outcome found by the court | No conviction: The product modification is not “unreasonably anti-competitive” |

No conviction: Comparing the quality of two devices is not a conclusive evidence |

Conviction: the new product is easier to use, but “the real reason” of the modification is anti-competitive |

Conviction: Deleting the possibility to remove a software from the operating system (practice n1) and programing the operating system so to bug when certain files related to Internet Explorer are deleted (practice n3) has no pro-competitive justification No conviction: No conviction: |

Conviction: The operating system may have properly functioned even in the absence of Windows Media Player |

| Application of the enhanced version of “no economic sense” test |

No conviction: The improvements may not be separated from the anti-competitive effects |

Conviction: Removing compatibility is unrelated from improving the camera |

No conviction: Improving the needle system may not be done without removing compatibility |

Conviction: Practices n1 and n3 made economic sense only because they produced an anti-competitive effect Inability to judge: No No conviction: |

No conviction: The integration of WMP to the operating system is not anti-competitive in itself |

| Name & date of the case | HDC Medical v. Minntech Corporation (2007) |

Intel US (2010) | Allied c. Tyco (2010) | iPod iTunes litigation (2014) |

| Outcome found by the court |

No conviction: Minntech provided an economic justification for its product modification that HDC could not prove to be false |

Mutual agreement: Intel has agreed to amend its practices for the future |

No conviction: The new design is an improvement establishing the superiority of the new product |

No conviction: iTunes 4.7: this version of iTunes is a real innovation in that it increases the security of the software No conviction: iTunes |

| Application of the enhanced version of “no economic sense” test |

No conviction: removing the product compatibility is inseparable from the improvement made to the product |

Inability to judge: lack of information on the possibility to distinguish between the improvement and the deleting of compatibility |

No conviction: Removing the product compatibility is the reason explaining the improvement |

Inability to judge: The documents allowing to analyze whether changes made to iTunes 4.7 were justified for technical reasons are sealed Inability to judge: The |

* Thibault Schrepel (Ph.D., LL.M.) is a research associate at the Sorbonne-Business & Finance Institute, University of Paris I Pantheon-Sorbonne. He leads the “innovation” team of Rules for Growth and is the Revue Concurrentialiste creator. His personal website is www.thibaultschrepel.com. Your comments on this article are more than welcome (thibaultschrepel@me.com). I would like to thank the editors of the NYU Journal of Intellectual Property & Entertainment Law for their consstructive editing.

[1]

Type-I errors, also called “false positives,” occur when a court—or a competition authority—wrongly condemns a company for having implemented practices which, in fact, are not anti-competitive. On the contrary, type II errors, also known as “false negatives,” occur in the absence of condemnation of a practice that is anti-competitive and should therefore have been condemned.

[2] For an overview, see Michael L. Katz & Howard A. Shelanski, “Schumpeterian” Competition and Antitrust Policy in High-Tech Markets, 14 Cᴏᴍᴘᴇᴛɪᴛɪᴏɴ 47 (2005).

[3] OECD Policy Roundtables, Predatory Foreclosure, DAF/COMP(2005)14, at 48-59.

[4] Predatory innovation, which we previously identified as being one of the key issues in terms of high-tech markets, illustrates our point. See Thibault Schrepel, Predatory Innovation: The Definite Need for Legal Recognition, SMU Sᴄɪ. & Tᴇᴄʜ. L. Rᴇᴠ. (forthcoming 2018); see also, Thibault Schrepel, Predatory innovation: A response to Suzanne Van Arsdale & Cody Venzke, Hᴀʀᴠ. J.L. & Tᴇᴄʜ. Dig. (2017), http://jolt.law.harvard.edu/digest/digest-note-predatory-innovation.

[5] OECD Policy Roundtables, Competition on the Merits, DAF/COMP(2005)27, at 23.

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] Case COMP/C-3/37.792—Sun Microsystems, Inc. v. Microsoft Corp., Comm’n

Decision (Apr. 21, 2004), available at

http://ec.europa.eu/competition/antitrust/cases/dec_docs/37792/37792_4177_1.pdf [hereinafter “Microsoft Decision”].

[9] The OECD has recently devoted several roundtables to the subject. See

OECD Policy Roundtables, Algorithms and Collusion, DAF/COMP(2017)4; see also OECD Policy Roundtables, Big Data: Bringing Competition Policy to The Digital Era, DAF/COMP(2016)14. Most of the world-leading competition authorities have contributed to them too.

[10] See generally Nicholas S. Smith, Innovative Breakthrough or Monopoly Bullying? Determining Antitrust Liability of Dominant Firms in Exclusionary Product Redesign Cases, 84 Tᴇᴍᴘ. L. Rᴇᴠ. 995 (2012) (explaining antitrust law objectives).

[11] Id.

at 1016.

[12]

As a reminder, type-I errors, also called “false positives,” occur when a court—or a competition authority—wrongly condemns a company for having implemented practices which, in fact, are not anti-competitive.

[13] See Smith, supra note 10, at 1018.

[14]

See John B. Kirkwood & Robert H. Lande, The Fundamental Goal of Antitrust: Protecting Consumers, Not Increasing Efficiency, 84 Nᴏᴛʀᴇ Dᴀᴍᴇ L. Rᴇᴠ. 191 (2008); see also Nicolas Petit, European Competition Law, 143 (Montchrestien, 2012) (text in French) (“the European competition law seems to have decided in favor of this theory.”).

[15]

We argued that the Neo-Chicago School should seek that goal. See Thibault Schrepel, Applying the Neo-Chicago School’s Framework To High-Tech Markets, Rᴇᴠᴜᴇ Cᴏɴᴄᴜʀʀᴇɴᴛɪᴀʟɪsᴛᴇ (May 6, 2016), https://leconcurrentialiste.com/2016/05/06/neo-chicago-school-high-tech-markets. Two authors further developed the premises of that school of thought. See David S. Evans & A. Jorge Padilla, Designing Antitrust Rules for Assessing Unilateral Practices: A Neo-Chicago Approach, 72 U. Cʜɪ. L. Rᴇᴠ. 27, 33 (2005); see also Thomas A. Lambert & Alden F. Abbott, Recognizing the Limits of Antitrust, 11 J. Cᴏᴍᴘ. L. & Eᴄᴏɴ. 791, 793 (2015) (“Neo-Chicagoans reason that ‘market self-regulation is often superior to government regulation . . .’”).

[16] See Herbert Hovenkamp, Antitrust and Innovation: Where We Are and Where We Should Be Going, 77 Aɴᴛɪᴛʀᴜsᴛ L.J. 749, 751 (2011) (“[T]he gains to be had from innovation are larger than the gains from simple production and trading under constant technology.”).

[17] OECD Policy Roundtables, Two-Sided Markets, DAF/COMP(2009)20, 14 (“Firms sometimes use non-price strategies, such as exclusive contracts and product tying, to limit competition or foreclose the market to rivals. These practices have been at the centre of several important competition cases involving two-sided markets.”).

[18] Mark S. Popofsky, Defining Exclusionary Conduct: Section 2, the Rule of Reason, and the Unifying Principle Underlying Antitrust Rules, 73 Aɴᴛɪᴛʀᴜsᴛ L.J. 435, 477 (2006); see Frank H. Easterbrook, Cyberspace and the Law of the Horse, 1996 U. Cʜɪ. Legal F. 207, 215 (1996) (explaining the necessity to create a straightforward legal standard).

[20] Id. This study of several hundred pages is extremely rich and remains the reference on the law.

[21] Id. at 23.

[22] See John Temple Lang, Comparing Microsoft and Google: The Concept of Exclusionary Abuse, 39 Wᴏʀʟᴅ Cᴏᴍᴘᴇᴛɪᴛɪᴏɴ & Eᴄᴏɴ. Rev. 5, 5 (2016).

[23] In terms of predatory innovation, an author already underlined in 1988 that all decisions dealing with the subject had little coherence, and that remains unchanged to this day. See Ross D. Petty, Antitrust and Innovation: Are Product Modifications Ever Predatory, 22 Sᴜffᴏʟᴋ U. L. Rᴇᴠ. 997, 1028 (1988) (“The decisions to date offer little guidance on how to distinguish a predatory product innovation, if such exists, from a legitimate innovation.”).

[24] See Hillary Greene, Muzzling Antitrust: Information Products, Innovation and Free Speech, 95 B.U. L. Rᴇᴠ. 35, 72 (2015) (“Unfortunately, the courts have failed to carry over important nuances from the articulation of the legal theory of the anticompetitive product design to that theory’s practical application.”).

[25]

Jonathan M. Jacobson & Scott A. Sher, “No Economic Sense” Makes No Sense for Exclusive Dealing, 73 Aɴᴛɪᴛʀᴜsᴛ L.J. 779, 782 (2006); see also Herbert Hovenkamp, The Harvard and Chicago Schools and the Dominant Firm, in How the Chicago School Overshot the Mark: The Effect of Conservative Economic Analysis on US Antitrust

(Robert Pitofsky ed., Oxford Univ. Press, 2008).

[26]

Jonathan B. Baker, Preserving a Political Bargain: The Political Economy of the Non-interventionist Challenge to Monopolization Enforcement, 76 Aɴᴛɪᴛʀᴜsᴛ L.J. 605, 616 (2010).

[27] Gregory J. Werden, The “No Economic Sense” Test for Exclusionary Conduct, 31 J. Corp. L. 293, 301 (2006).

[28]

Id.

[29] Id.

[31] Gregory J. Werden, Identifying Exclusionary Conduct Under Section 2: The “No Economic Sense” Test, 73 Aɴᴛɪᴛʀᴜsᴛ L.J. 413, 417 (2006).

[32] Id.

[33] Janusz Ordover & Robert Willig, An Economic Definition of Predation: Pricing and Product Innovation, 91 Yale L.J. 8, 11 (1981).

[35] See Richard J. Gilbert, Holding Innovation to an Antitrust Standard, 3 Cᴏᴍᴘᴇᴛɪᴛɪᴏɴ Pᴏʟ’ʏ Iɴᴛ’ʟ 47, 77 (2007).