Jorge L. Contreras*

Download a PDF version of this article here.

The proliferation of international jurisdictional conflicts and competing “anti-suit injunctions” in litigation over the licensing of standards-essential patents has raised concerns among policymakers in the United States, Europe, and China. This Essay recommends that while international bodies develop a more comprehensive, efficient, and transparent methodology for assessing global “fair, reasonable and nondiscriminatory” (“FRAND”) royalty rates, national courts voluntarily “stand down” from assessing global FRAND rates and instead limit their assessments to FRAND royalty rates applicable to patents within their own jurisdictions.

Introduction

Thanks to the decades-long efforts of international standards development organizations (“SDOs”), today’s electronic devices seamlessly communicate and interconnect via widely adopted protocols like 3G/4G/5G, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and USB. Because of these standards, markets and supply chains for computers, networking equipment, and communication devices have largely become global. Global product markets, however, also mean global litigation, and disputes over patents covering some of these standards (so-called “standards-essential patents” or “SEPs”) are routinely fought in a half-dozen or more jurisdictions around the world.

The crux of many of these disputes is whether the holder of a SEP has honored the commitment that it has made to an SDO to license that SEP to manufacturers of standardized products (often called “implementers”) on terms that are “fair, reasonable and nondiscriminatory” (“FRAND”). Because there is no generally accepted definition of FRAND, and SDOs offer little guidance regarding its details, disputes have arisen regarding the royalty rates and other terms that SEP holders must offer to potential licensees in order to comply with their FRAND commitments.1

I. National Versus Global FRAND Rates

Courts adjudicating FRAND disputes face a dilemma. On the one hand, patents are issued under national law and, by definition, have legal effect only in the issuing jurisdiction. On the other hand, the parties to FRAND disputes are often multinational corporations with operations (and patents) in jurisdictions around the world. Moreover, many of these parties privately negotiate worldwide license agreements to cover their global operations without regard for the particular patents issued in any given country. In resolving a dispute over FRAND royalty rates, a court must thus decide whether to focus only on the patents issued and asserted in its own jurisdiction or to consider the global business relationship between the parties. Even though a national court typically lacks the authority to adjudicate damages with respect to the infringement of foreign patents, the fact that FRAND disputes are essentially contractual disputes gives a national court the jurisdictional authority to determine a global rate for the portfolio licensed under the agreement in question (as opposed to infringement damages for patents in other jurisdictions).2

In some cases, courts have limited their assessment of FRAND royalties to the national patents that have been asserted. These cases include Microsoft v. Motorola,3 In re Innovatio,4 Ericsson v. D-Link,5 and Optis v. Huawei.6 In each of these cases, a U.S. district judge or jury determined a FRAND royalty rate and awarded damages to the SEP holder based on valid and infringed U.S. patents.

However, in 2017, the U.K. High Court for Patents ruled in Unwired Planet v. Huawei7 that it was authorized to set the terms of a global FRAND license between the parties, covering not only the SEP holder’s U.K. patents, but also foreign patents covered by its FRAND commitment. In that case, the SEP holder, Unwired Planet, had offered a smartphone manufacturer, Huawei, a worldwide license under the asserted SEPs. Huawei argued that it only wished to obtain a license under the U.K. patents that Unwired Planet had asserted, and that Unwired Planet’s insistence on a worldwide license was unreasonable.8 In evaluating the reasonableness of the license offer, the court first observed that the “vast majority” of SEP licenses are granted on a worldwide basis with occasional exclusions.9 It then observed that both parties were global companies: Unwired Planet held patents in 42 countries, while Huawei had operations in 58 countries.10 As a result, it concluded that “a licensor and licensee acting reasonably and on a willing basis would agree on a worldwide licence.”11 In contrast, the court reasoned, country-by-country licensing in such a situation would be highly inefficient.12 Accordingly, the court determined the royalty rates across the globe that would enable Unwired Planet to comply with its FRAND obligation and ruled that Huawei accept a license on these terms or suffer an injunction against the sale of infringing products in the United Kingdom.13

A similar approach was taken by the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California in TCL v. Ericsson,14 though that court’s global FRAND determination was made with the consent of both parties. Most recently, courts in China have proven willing to assess FRAND royalty rates on a global basis (see below).

The ability of one national court to determine FRAND rates applicable to patents around the world can lead to two forms of a legal “race.” First is a “race to the bottom” among jurisdictions—a well-documented phenomenon in which jurisdictions intentionally adapt their rules, procedures, and substantive outlook to attract litigants.15 Second, differences among jurisdictions are likely to encourage parties to initiate litigation in the jurisdiction most favorable to their positions as quickly as possible, often to foreclose a later suit in a less favorable jurisdiction. This situation is referred to as a “race to judgment” or a “race to the courthouse,” which may prematurely drive parties to litigation rather than negotiation or settlement.16

II. Anti-Suit Injunctions

An anti-suit injunction (“ASI”) is an interlocutory in personam remedy issued by a court in one jurisdiction to prohibit a litigant from initiating or continuing parallel litigation in another jurisdiction. While an ASI can bind a party to litigation, it has no binding effect on a foreign court.

ASIs have been issued for centuries in a wide range of commercial, antitrust, and bankruptcy actions.17 In recent years, however, the most significant use of ASIs has been in connection with global FRAND disputes. For example, a court reviewing a SEP holder’s compliance with a FRAND licensing commitment may issue an ASI to prevent the SEP holder from pursuing foreign FRAND rate determination or infringement claims until the first court has completed its adjudication of the licensing terms.

In the United States, courts considering issuing ASIs follow some variant of the three-part framework developed by the Ninth Circuit in E. & J. Gallo Winery v. Andina Licores.18 Under the Gallo framework, a court must first determine whether the parties and the issues in the action in which the ASI is sought (“the local action”) are functionally equivalent to those in the action sought to be enjoined (“the foreign action”). If so, the court must determine whether resolution of the local action would be dispositive of the foreign action. The court must then assess whether any of the four factors identified by the Fifth Circuit in In re Unterweser Reederei19 are present. These factors include whether the foreign litigation would (1) frustrate a policy of the issuing forum; (2) be vexatious or oppressive; (3) threaten the issuing court’s jurisdiction; or (4) prejudice other equitable considerations. If at least one of the Unterweser factors is present, the court must ask whether the injunction will have a significant impact on international comity.20 If not, then the ASI may be issued.

III. ASIs in FRAND Cases

The first notable ASI in a FRAND case was issued by the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington in Microsoft v. Motorola,21 the facts of which are fairly typical. In that case, Microsoft alleged that Motorola breached its commitment to offer Microsoft a FRAND license as required under the rules of two SDOs.22 As a result, Microsoft sued Motorola for breach of contract in the Western District of Washington. Six months later, Motorola sued Microsoft for patent infringement in Germany. The German court found infringement and enjoined Microsoft from selling infringing products in Germany. In response, Microsoft sought an ASI from the U.S. court to prevent Motorola from enforcing the German injunction until the resolution of the U.S. action. Finding that the resolution of the U.S. matter would dispose of the German matter (i.e., if Motorola were found to have breached its FRAND obligations, then Motorola would not be entitled to seek injunctive relief against Microsoft in any jurisdiction, including Germany), the U.S. court entered the ASI against Motorola. On appeal, the Ninth Circuit affirmed.

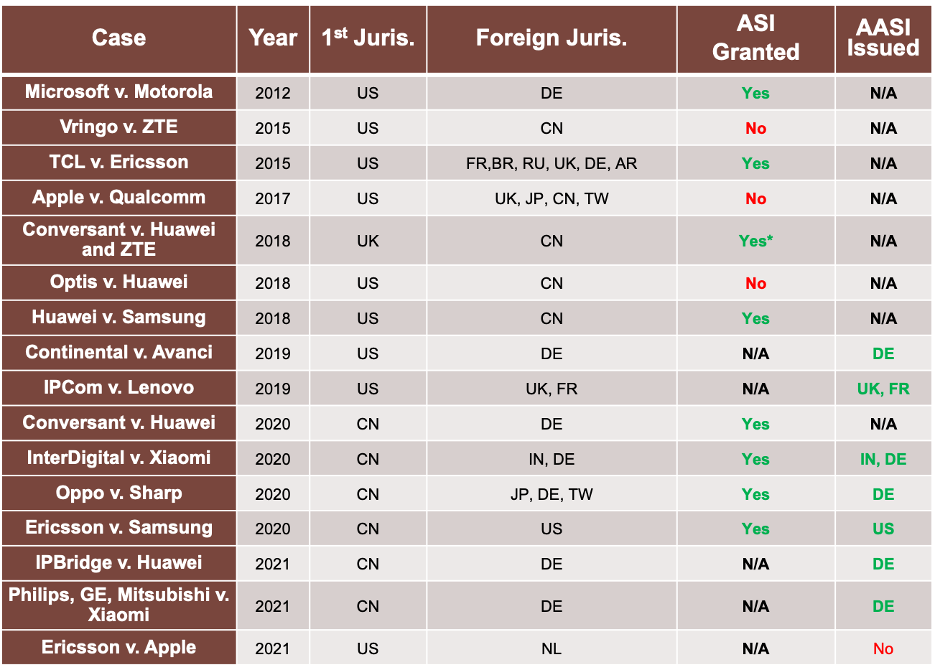

Several other ASI actions followed in U.S. FRAND cases, including Vringo v. ZTE,23 TCL v. Ericsson,24 Apple v. Qualcomm,25 Optis v. Huawei,26 and Huawei v. Samsung.27 The courts granted ASIs in about half of these cases (see Table 1).28

A. Anti-Anti-Suit Injunctions

By 2018, international litigants and courts began to resist the imposition of ASIs by U.S. courts through anti-anti-suit injunctions (“AASIs”). Like an ASI, an AASI operates in personam, prohibiting a litigant from taking a particular action (seeking or enforcing an ASI), rather than purporting to restrain the authority of a foreign court.29

In IPCom v. Lenovo,30 a U.S. district court granted an ASI preventing IPCom from pursuing parallel infringement litigation against Lenovo outside the United States. In response, IPCom brought an action in France seeking to prevent Lenovo from enforcing the U.S. ASI. The French court granted the AASI, holding that, except under certain circumstances, ASIs are contrary to French ordre public and “seeking an anti-suit injunction—such as the one pursued by Lenovo in California—would infringe upon IPCom’s fundamental rights pursuant to French laws . . . .”31 A U.K. court also issued an AASI in favor of IPCom, reasoning that “it would be vexatious and oppressive to IPCom if it were deprived entirely of its right to litigate infringement and validity of [its U.K. patent].”32

A German court responded similarly in Continental v. Avanci,33 issuing an AASI to prevent the enforcement of a U.S. ASI that sought to prevent a number of SEP holders from pursuing litigation in Germany. The German court found that the requested ASI would have been incompatible with German law.34

B. China Takes Center Stage

Though Chinese judicial actions have been the targets of ASI motions in U.S. cases since at least 2015, it wasn’t until 2020 that Chinese courts began to issue ASIs of their own. Then, during the course of 2020 alone, Chinese courts issued an unprecedented four ASIs in major FRAND cases.

Three of these cases—Conversant v. Huawei,35 InterDigital v. Xiaomi,36 and OPPO v. Sharp37—involved a non-Chinese company’s assertion of SEPs against a Chinese manufacturer. In each case, a Chinese court granted an ASI requested by the Chinese manufacturer, enjoining parallel actions in Germany (Conversant), Germany and India (InterDigital), and Germany, Japan, and Taiwan (OPPO).38 In all three cases, the Chinese court imposed a penalty of 1 million yuan (approximately US$150,000) per day for any violation of the ASI.39 In response to these Chinese ASIs, courts in Germany40 and India41 issued AASIs.

Unlike the other three Chinese cases, Ericsson v. Samsung42 did not involve a Chinese party (Ericsson is Swedish, and Samsung is South Korean). The case related to an existing SEP cross-license between Samsung and Ericsson that was due to expire at the end of 2020. On December 7, Samsung sought a FRAND royalty rate determination for Ericsson’s SEPs in the Wuhan Intermediate People’s Court. On December 11, Ericsson sued Samsung for infringement in the Eastern District of Texas. In response, Samsung asked the Wuhan court for an ASI preventing Ericsson from seeking relief in the United States. On December 25, the Wuhan court issued the ASI, which also prohibited Ericsson from seeking to negate the ASI in Texas (i.e., an “AAASI”). The Texas court quickly issued a temporary restraining order and then a preliminary injunction, prohibiting Samsung’s enforcement of the Wuhan ASI and requiring Samsung to indemnify Ericsson against any penalties imposed by the Wuhan court.43 Ericsson v. Samsung is a particularly salient example of forum shopping in FRAND cases, as both parties sought to litigate in jurisdictions other than their “home” jurisdictions, presumably due to the advantages that they perceived in the laws and procedures of those jurisdictions.

In response to the growing popularity of ASIs in China, courts in Europe have begun issuing pre-emptive AASIs to prevent litigants from seeking and enforcing ASIs issued by Chinese courts. In two recent cases, IPBridge v. Huawei and Philips, General Electric and Mitsubishi Electric v. Xiamoi, German courts in Düsseldorf and Munich have granted pre-emptive AASIs prohibiting Chinese parties from seeking ASIs in China before any such ASIs have been sought.44

The remarkably rapid actions and counter-actions in all of these cases exemplify the “race to the courthouse” discussed above.

IV. Concern from Policymakers

The complexity, cost, and unpredictability of high-stakes global FRAND disputes have increased markedly with the introduction of ASIs, AASIs, and AAASIs, and policymakers around the world have taken notice. For example, the U.S. Trade Representative, in her 2021 Special 301 Report, specifically identified China’s increased use of ASIs as “worrying” in the context of international trade.45 In its Intellectual Property Action Plan, the European Commission observed that “very broad extraterritorial anti-suit injunctions” are particularly challenging to European companies operating internationally.46 In July 2021, the European Union issued a formal request for information to China under Section 63.3 of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (“TRIPS Agreement”), asking for clarification, among other things, regarding the legal basis for blocking the enforcement of European actions in Conversant and OPPO.47

Despite these expressions of concern, strategic races to the courthouse will likely continue until a more rational, transparent, and comprehensive system for determining FRAND royalty rates is established. In the past, I have proposed a number of potential solutions to the FRAND litigation race and the inefficient, non-transparent, and inconsistent negotiation of FRAND royalties, including the use of interpleader to determine aggregate FRAND royalty rates in a single proceeding that involves all interested parties,48 the collective negotiation of aggregate royalty rates applicable to a particular standard,49 and the establishment of a non-governmental FRAND rate-setting tribunal.50 Professor Thomas Cotter has suggested that national governments seek to develop consensus, or at least best practices, around certain contentious FRAND calculation issues, which could alleviate “race to the bottom” concerns that arise from current jurisdictional differences.51 Additionally, the European Commission’s Expert Group on Standards Essential Patents has made a range of proposals, both substantive and procedural.52 Yet, each of these reforms will take time to develop, enact, and implement. So, what should be done in the meantime to stem the increasing incidence of jurisdictional clashes in global FRAND litigation?

V. Judicial Restraint and FRAND Litigation

As noted above, a court confronted with a global FRAND case has two basic choices. It may determine FRAND royalty rates associated with the national patents issued in its jurisdiction, or it may determine the FRAND royalty rates applicable around the world. The latter option, pioneered by the U.K. courts in Unwired Planet and now embraced by courts in the United States and China, has led to the jurisdictional competition exemplified by the cases discussed above. It is the first option—a court’s assessment of royalty rates applicable to patents issued in its own jurisdiction—that will eliminate costly and chaotic jockeying among jurisdictions and parties. This approach was adequate for the “first generation” of FRAND royalty determination cases (e.g., Innovatio and D-Link, discussed above) and is grounded in judicial restraint and international comity.

Thus, while courts around the world may have the legal authority to determine global FRAND rates as incidental to contractual commitments, doing so may not be in the best interests of the parties or the market. Accordingly, courts that are considering FRAND cases should voluntarily refrain from determining global FRAND rates and instead limit their determinations to royalty rates for patents issued in their own jurisdictions, at least until a more effective global system is in place to assess FRAND rates on a comprehensive basis.

While some predict that such a voluntary relinquishment of global rate-setting authority could result in FRAND rates that vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction,53 this is not an undesirable result given that patent portfolios, substantive patent laws, and product markets also vary from country to country. Moreover, the inconsistency that individual parties may experience by having FRAND rates vary from country to country may, in fact, lend greater consistency to the global FRAND licensing market, as it will eliminate the extreme variations in global FRAND rates that occur from party to party. National patent royalty rates are the norm in patent disputes. The fact that parties may privately negotiate blanket royalty rates in global license agreements—the underlying motivation for the U.K. court’s decision to set global rates in Unwired Planet—does not change the national character of patent law. Until patent law is unified through a single, global system (an unlikely prospect for the foreseeable future), courts will, and should, continue to adjudicate patent remedies on a national basis.54

There are numerous ways to coordinate international judicial activity to achieve such an accord. The most direct route would be a formal treaty agreement. However, treaty negotiations are time-consuming and politically fraught. Less formal approaches may thus be more expedient in this context. Judges from around the world meet regularly at events sponsored by the International Bar Association, the American Bar Association International Law Section, and other groups. The U.S.-based Judicial Conference Committee on International Judicial Relations coordinates interactions between members of the U.S. judiciary and foreign judicial systems,55 the American Law Institute has developed a comprehensive set of principles governing jurisdiction, choice of law, and judgments in transnational disputes,56 and the World Intellectual Property Organization is coordinating an international effort on patent case adjudication in which, among others, the Chinese courts are currently participating.57 Any of these organizations or fora could serve as a focal point for much-needed harmonization of judicial practices regarding global FRAND disputes.

Conclusion

The proliferation of international jurisdictional conflicts and competing anti-suit injunctions in FRAND litigation has raised legitimate concerns among policymakers around the world. Such conflicts have already resulted in the predicted “race to the courthouse” and “race to the bottom” in FRAND disputes with no end in sight. This Essay suggests that, in order to give international bodies time to develop a more comprehensive, efficient, and transparent methodology for resolving FRAND licensing disputes, national courts should voluntarily “stand down” from assessing global FRAND royalty rates and instead limit their adjudication to royalties covering patents issued within their own jurisdictions. While such a limitation on judicial authority is not mandated by national law or international agreement, this modest exercise of judicial restraint could clear the way for these important issues to be resolved in a more rational, transparent, and balanced manner.

Footnotes

* Presidential Scholar and Professor of Law, University of Utah S.J. Quinney College of Law.

- See generally Jorge L. Contreras, Global Rate Setting: A Solution for Standards-Essential Patents?, 94 Wash. L. Rev. 701, 713-26 (2019) (describing a range of disputed issues relating to FRAND).

- For a discussion of the differences between adjudication of patent damages and FRAND royalty rates, see Jorge L. Contreras et al., The Effect of FRAND Commitments on Patent Remedies, in Patent Remedies and Complex Products: Toward a Global Consensus 160, 161-63 (C. Bradford Biddle et al. eds., 2019).

- Microsoft v. Motorola, 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 60233 (W.D. Wash. 2013), aff’d 795 F.3d 1024 (9th Cir. 2015) (recognizing the existence of non-U.S. patents but focusing its analysis only on U.S. patents).

- In re Innovatio IP Ventures, LLC, 2013 U.S. DIST. Lexis 144061 (N.D. Ill. 2013).

- Ericsson, Inc. v. D-Link Sys., Inc., 773 F.3d 1201, 1225-29 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

- Optis v. Huawei, No. 2:17-cv-123-JRG-RSP, 2018 WL 476054 (E.D. Tex. Jan. 18, 2018).

- Unwired Planet Int’l Ltd. v. Huawei Techs. Co. [2017] EWHC (Pat) 711 (Eng.), aff’d [2020] UKSC 37.

- Id. at ¶ 524.

- Id. at ¶ 534.

- Id. at ¶ 538.

- Id. at ¶ 543.

- Id. at ¶ 543-44 (referring to such a prospect as “madness”).

- Id. at ¶ 537.

- TCL Commc’n Tech. Holdings, Ltd. v. Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson, No. CV 15-2370 JVS(DFMx), 2018 WL 4488286 at *50-52 (C.D. Cal. 2018), rev’d in part, vacated in part, and remanded 943 F.3d 1360 (Fed. Cir. 2019).

- See Jorge L. Contreras, The New Extraterritoriality: FRAND Royalties, Anti-Suit Injunctions and the Global Race to the Bottom in Disputes over Standards-Essential Patents, 25 B.U. J. Sci. & Tech. L. 251, 280-83 (2019).

- See id. at 283-86.

- For an overview and history of the U.S. approach to anti-suit injunctions, see Trevor C. Hartley, Comity and the Use of Antisuit Injunctions in International Litigation, 35 Am. J. Comp. L. 487, 489-90 (1987); George A. Bermann, The Use of Anti-Suit Injunctions in International Litigation, 28 Colum. J. Transnat’l. L. 589, 593-94 (1990); S.I. Strong, Anti-Suit Injunctions in Judicial and Arbitral Procedures in the United States, 66 Am. J. Comp. L. 153, 155-56 (2018).

- E. & J. Gallo Winery v. Andina Licores S.A., 446 F.3d 984, 991 (9th Cir. 2006). See generally Strong, supra note 17, at 159-64.

- In re Unterweser Reederei, GmbH, 428 F.2d 888, 890 (5th Cir. 1970), aff’d on reh’g, 446 F.2d 907 (5th Cir. 1971), rev’d on other grounds sub nom. M/S Bremen v. Zapata Off-Shore Co., 407 U.S. 1 (1972).

- Gallo, 446 F.3d at 994 (“Comity is ‘the recognition which one nation allows within its territory to the legislative, executive or judicial acts of another nation, having due regard both to international duty and convenience, and to the rights of its own citizens, or of other persons who are under the protection of its laws.’”) (quoting Hilton v. Guyot, 159 U.S. 113, 164 (1895)).

- Microsoft Corp. v. Motorola, Inc., 871 F. Supp. 2d 1089, 1097 (W.D. Wash. 2012), aff’d, 696 F.3d 872 (9th Cir. 2012).

- The SDOs in question are the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Standards Association (“IEEE-SA”), which publishes the 802.11 “Wi-Fi” wireless networking standard, and the International Organization for Standardization (“ISO”), which publishes the H.264 video compression standard.

- Vringo, Inc. v. ZTE Corp., No. 14-cv-4988 (LAK), 2015 WL 3498634, at *1 (S.D.N.Y. June 3, 2015).

- TCL Commc’n Tech. Holdings v. Telefonaktienbolaget LM Ericsson, No. 8:14-cv-00341-JVS-AN, 2015 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 191512, at *10 (C.D. Cal. Jun. 29, 2015).

- Order Denying Anti-Suit Injunction, at 5-6, Apple Inc. v. Qualcomm Inc., No. 3:17-cv-00108-GPC-MDD (S.D. Cal. Sep. 7, 2017).

- Order, Optis Wireless Tech., LLC v. Huawei Techs. Co., No. 2:17-Cv-00123-JRG-RSP (E.D. Tex. May 14, 2018).

- Order Granting Samsung’s Motion for Antisuit Injunction, Huawei Techs. Co. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No 3:16-cv-02787-WHO (N.D. Cal. Apr. 13, 2018).

- For a summary of the facts and holdings of these cases, see Contreras, supra note 15, at 265-78.

- The leading U.S. case regarding AASIs is Laker Airways Ltd. v. Sabena, Belgian World Airlines, 731 F.2d 909 (D.C. Cir. 1984). See Alexander Shaknes, Anti-Suit and Anti-Anti-Suit Injunctions in Multi-Jurisdictional Proceedings, 21 NYSBA Int’l L. Practicum 96, 100 (2008).

- Lenovo (U.S.) Inc. v. IPCom GmbH & Co., No. 19-1389 (N.D. Cal. Mar. 19, 2019).

- Tribunal de grande instance [TGI] [Paris Court of First Instance] Paris, Nov. 8, 2019, 19/59311, aff’d Cour d’appel [CA] [Court of Appeal of Paris] Paris, Mar. 3, 2020, 19/21426. An English translation is available at http://caselaw.4ipcouncil.com/french-court-decisions/ipcom-v-lenovo-court-appeal-paris-rg-1921426; see also Enrico Bonadio & Luke McDonagh, Paris Court Grants a SEP Anti-Anti-Suit Injunction in IPCom v Lenovo: A Worrying Decision in Uncertain Times?, J. Intell. Prop. L. & Prac. (forthcoming).

- IPCom GmbH & Co. v. Lenovo Tech. (U.K.) Ltd. [2019] EWHC 3030 (Pat) 52 (Eng.).

- Cont’l Auto. Sys., Inc. v. Avanci LLC, No. 19-cv-2520 (N.D. Cal. Jun. 12, 2019).

- Landgericht München I, Oct. 11, 2019, 21 O 9333/19, https://www.gesetze-bayern.de/Content/Document/Y-300-Z-BECKRS-B-2019-N-25536?hl=true; Landgericht München I, Dec. 12, 2019, 21 O 9512/19, https://www.gesetze-bayern.de/Content/Document/Y-300-Z-BECKRS-B-2019-N-%2033196?hl=true&AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1.

- Huawei Techs. Corp. v. Conversant Wireless Licensing S.A.R.L. (2019) Zui Gao Fa Zhi Min Zhong No. 732, 733, 734 Part I (Sup. People’s Ct. Aug. 28, 2020). An unofficial English translation is available at https://patentlyo.com/media/2020/10/Huawei-V.-Conversant-judgment-translated-10-17-2020.pdf. For a more detailed discussion, see Yang Yu & Jorge L. Contreras, Will China’s New Anti-Suit Injunctions Shift the Balance of Global FRAND Litigation?, Patently-O Blog (Oct. 22, 2020), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3725921.

- Xiaomi Commc’n Tech. Co. v. InterDigital Inc. (2020) E 01 Zhi Min Chu 169 (Wuhan Interm. People’s Ct. Sept. 23, 2020). An unofficial English translation is available at https://patentlyo.com/media/2020/10/Xiaomi-v.-InterDigital-decision-trans-10-17-2020.pdf. For a more detailed discussion, see Yu & Contreras, supra note 35.

- Guangdong OPPO Mobile Telecomm. Corp. v. Sharp Corp. (2020) Yue 03 Min Chu No.689-1 (Shenzhen Intermed. People’s Ct. Dec. 3, 2020). The Supreme People’s Court upheld the Shenzhen ruling on Sept. 2, 2021. See Bing Zhao, Chinese Judges Can Set Global SEP Rates and Licence Terms, Supreme People’s Court Confirms, IAM (Sep. 2, 2021), https://www.iam-media.com/frandseps/chinese-courts-can-set-global-sep-rate-and-licensing-terms-spc-confirms.

- See Zeyu Huang, The Latest Development on Anti-Suit Injunction Wielded by Chinese Courts to Restrain Foreign Parallel Proceedings, Conflict Laws.net (July 9, 2021), https://conflictoflaws.net/2021/the-latest-development-on-anti-suit-injunction-wielded-by-chinese-courts-to-restrain-foreign-parallel-proceedings/ (discussing the ASIs in Conversant and OPPO); Gregory Glass, Delhi High Court Confirms India’s First Anti-Anti-Suit Injunction, Asia IP (May 13, 2021), https://asiaiplaw.com/article/delhi-high-court-confirms-indias-first-anti-anti-suit-injunction (discussing the ASI in InterDigital).

- See Huang, supra note 38; Glass, supra note 38.

- See Huang, supra note 38; Mathieu Klos, Munich Court Confirms AAAASI in SEP Battle Between InterDigital and Xiaomi, JUVE Pat. (Feb. 26, 2021), https://www.juve-patent.com/news-and-stories/cases/munich-court-confirms-aaaasi-in-sep-battle-between-interdigital-and-xiaomi/.

- See Glass, supra note 38.

- Samsung Elecs. Co. v. Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson (2020) E 01 Zhi Min Chu No. 743 (Wuhan Interm. People’s Ct. Dec. 25, 2020) (China).

- Memorandum Opinion and Preliminary Injunction, Ericsson Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 2:20-CV-00380-JRG, 2021 WL 89980 (E.D. Tex. Jan. 11, 2021).

- LG Düsseldorf, July 15, 2021, 4c O 73/20 openJur (Ger.); LG Düsseldorf, July 15, 2021, 4c O 74/20 openJur (Ger.); LG Düsseldorf, 4c O 75/20 openJur (Ger.); LG Munich, June 24, 2021, 7 O 36/21 openJur (Ger.).

- Off. of the U.S. Trade Rep., 2021 Special 301 Report 40 (2021).

- Eur. Comm’n, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee on the Regions (2020).

- Communication from the European Union to China, Request for Information Pursuant to Article 63.3 of the TRIPS Agreement, WTO Doc. IP/C/W/682 (July 6, 2021); see Jacob Schindler, China Brushes Off EU Request for More Information on Controversial SEP Decisions, Intell. Asset Mgt. (Sept. 8, 2021), https://www.iam-media.com/frandseps/china-brushes-eu-request-more-information-controversial-sep-decisions.

- Jason R. Bartlett & Jorge L. Contreras, Rationalizing FRAND Royalties: Can Interpleader Save the Internet of Things?, 36 Rev. Litig. 285 (2017).

- Jorge L. Contreras, Fixing FRAND: A Pseudo-Pool Approach to Standards-Based Patent Licensing, 79 Antitrust L.J. 47 (2013); Jorge L. Contreras, Aggregated Royalties for Top-Down FRAND Determinations: Revisiting ‘Joint Negotiation,’ 62 Antitrust Bull. 690 (2017).

- Contreras, supra note 1.

- Thomas F. Cotter, Is Global FRAND Litigation Spinning Out of Control?, 2021 Patently-O L.J. 1, 24 (2021). Cotter also suggests that governments “devote more effort to developing the sort of empirical evidence that would enhance rational decisionmaking with regard to SEPs and FRAND.” Id.

- SEPs Expert Group, Contribution to the Debate on SEPs (2021).

- See Richard Vary, Samsung v Ericsson and Why Anti-Anti-Suit Injunctions Are a Dead End, IAM (Mar. 17, 2021), https://www.iam-media.com/frandseps/samsung-v-ericsson-and-why-anti-anti-suit-injunctions-are-dead-end.

- See id.

- See Sam F. Halabi & Hon. Nanette K. Laughrey, Understanding the Judicial Conference Committee on International Judicial Relations, 99 Marq. L. Rev. 239 (2015).

- Am. Law. Inst., Intellectual Property: Principles Governing Jurisdiction, Choice Of Law, And Judgments In Transnational Disputes (2008); see also Rochelle Dreyfuss, The ALI Principles on Transnational Intellectual Property Disputes: Why Invite Conflicts?, 30 Brook. J. Int’l L. 819, 820-26 (2005) (discussing the motivation for the American Law Institute’s principles and drafting status); Graeme B. Dinwoodie, Developing a Private International Intellectual Property Law: The Demise of Territoriality?, 51 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 711, 720-21 (2009) (discussing the impact of the American Law Institute’s principles).

- See Mark Cohen, Three SPC Reports Document China’s Drive to Increase Its Global Role on IP Adjudication, China IPR (May 5, 2021), https://chinaipr.com/2021/05/05/three-spc-reports-document-chinas-drive-to-increase-its-global-role-on-ip-adjudication/.