M P Ram Mohan*, Aditya Gupta** & Vijay V. Venkitesh***

Download a PDF version of this article here.

The interaction between morality and law, particularly within the domain of intellectual property (IP), is fraught with complexities. This interplay becomes even more contentious when we consider ‘morality-based proscriptions’—explicit legislative carve-outs within IP law. These carve-outs are prevalent in trademark laws across 163 out of 164 WTO member states, highlighting their global significance. Previous academic studies have argued vagueness of these provisions, to the point of being potentially unconstitutional. Building on an earlier anecdotal and purposive study in the administration of these provisions within Indian law, this research constructs a novel dataset to scrutinize their implementation. Our dataset encompasses 1.6 million trademark examination reports filed between 2018 and 2022. Utilizing auto-coding techniques, we identified 140 applications that were objected to for containing scandalous or obscene material. A systematic analysis categorizes these objections into three distinct groups: those concurrently citing both relative and absolute grounds for refusal, instances where applicants successfully circumvented morality objections through ambiguity, and a notable absence of objections for potentially offensive marks. By providing empirical evidence, this study highlights the challenges inherent in the enforcement of these moral carve-outs, emphasizing the need for clearer guidelines and more consistent application.Introduction

Should a sexual-wellness company be allowed to use the image of a condom painted in a national flag as their trademark? Not only would the mark instigate abhorrence from the population of the country, it may also invoke prohibitory and criminal sanctions under the laws enacted to protect the dignity and sanctity of national symbols.1 However, would this outrage pacify if the mark was supplanted with the phrase, “We believe it is our patriotic duty to protect and save lives…Join us in promoting safer sex. Help eliminate AIDS”?2 This hypothetical is not a result of the authors’ overactive imagination. These were the facts of a dispute before the United States Patent and Trademark Office’s Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB).In 1989, Jay Critchley, an American artist and activist, artistically applied the United States Flag to a condom.3 Through his work, he wanted to communicate his “belief that the use of condoms is a patriotic act.”4 The campaign was such a success that Critchley decided to incorporate his artwork in a marketing campaign titled “Condoms with a Conscience.”5 He adopted a modified version of his artwork as a trademark “in a manner to suggest the American Flag.”6 His application for the registration of the mark was initially denied under Section 2(a) of the American Trademark Act, 1946 (Lanham Act), which prohibited the registration of scandalous and immoral marks.7 The United States Patents and Trademark Office (USPTO) adopted a civil-religious viewpoint, and argued that “the flag is a sacrosanct symbol whose association with condoms would necessarily give offense.”8 Critchley criticized the USPTO’s decision: “Basically, what they’re saying is that condoms are immoral and scandalous and anything to do with sex is dirty. It’s really Neanderthal, the whole attitude.”9 He successfully appealed the USPTO’s decision before the TTAB, securing the registration of his mark after a three year long legal battle.10

Jay Critchley’s case is not an isolated one. Trademark registrations have become the most recent battleground for the reclaiming of identity and destigmatization of stereotypes. One of these attempts was recently reviewed by the United States (U.S.) Supreme Court when an Asian-American band sought to “reclaim” the term “Slants” by registering it as their trademark.11 The all-Asian band made public appearances, participated in community outreach programs and even wrote a song to confirm their challenge of the racially charged slur.12 The lyrics of the song read, “We sing for the Japanese/And the Chinese/And all the dirty knees/Do you see me?”13 However, their attempt at registration was denied by the USPTO on the grounds of having adopted a disparaging mark.14 After a characteristic David versus Goliath legal battle against the USPTO, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the bar against disparaging marks was in violation of the First Amendment, thus striking down the trademark provision and allowing the band to register its mark.15

These cases are some of the instances which showcase the potential overreach of morality-based proscriptions on the trademark subject matter. These issues become even more pronounced in cases where these proscriptions are administered inconsistently, providing trademark examiners with unbridled discretion. In a pioneering empirical study, Barton Beebe and Jeanne Fromer examined 3.6 million trademark applications and found that the bar against “immoral or scandalous” marks is administered inconsistently by the USPTO.16

The present study represents a first of its kind effort by the authors to replicate Beebe and Fromer’s study in the Indian context, studying the bar against marks containing scandalous or obscene content embodied in Section 9(2)(c) of the Trade Marks Act of 1999.17 Part 1 comments on the origin and controversy regarding morality-based proscriptions in international trademark law. Part 2 identifies the legislative lineage and relevance of Section 9(2)(c) in Indian trademark law. Part 3 comments on the importance of providing bulk datasets for research and explains the novel dataset created by the authors. Part 4 provides some basic statistics and trends observed by the authors in their dataset. Part 5 applies the methodology suggested by Beebe and Fromer to examine the administration of Section 9(2)(c) by the Registrar of Trademarks in India.

I. The question of morality-based proscriptions

The precepts of intellectual property law are not completely divorced from moral and social facets. Not only does intellectual property law engender a lively debate about the foundational role of morality in the grant of monopolies, but it also sparks an ongoing debate regarding the continued role of moral precepts in the developing new IP standards.18 Some scholars maintain that IP should evolve in an ethical, principled, and moral manner, harmonizing with the tapestry of societal values.19 Yet, amidst this lively discourse, one realm where the hand of moral standards firmly grasps intellectual property law is its strategic alignment to prevent clashes with an imagined community moral compass. A prime example of such alignment is evident in the exclusions to IP protections, most eminently in trademark law.

A. The Inconsistency in Administering Morality-Based Trademark Restrictions

Trademark law, like all regulatory regimes, delimits the subject matter it engages with. The limitations that the law places on trademark subject matter are often couched in the language of economic efficiencies.20 However, there is one body of limitations that derive their legitimacy from moral justifications: morality-based proscriptions.21 The first instance of statutory language invoking such moral considerations can be traced back to England’s Trade Marks Registrations Act of 1875, which explicitly prohibited the registration of “scandalous designs” as trademarks.22 While the Westminster Assembly decided not to provide statutory protection to messages that violated prevailing social standards, they did not offer any guidance on how to assess these violations.23

Despite the inherent ambiguity in the meaning and the scope of application of the morality-based exclusions in trademark law, they were adopted into the international trademark framework through the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property of 1883.24 The provision allowed member countries to reject marks that are “contrary to morality or public order.”25 Since the inception of the Paris Convention, morality-based exclusions have been embraced by 163 out of the 164 member states of the World Trade Organization.26

The cumulative effect of such exclusions is that signs and marks which are perceived as morally unacceptable are precluded from the benefits afforded by trademark registration. The innate unpredictability of these exclusions has been a subject of repeated criticism. Many scholars have cited the inconsistency in the application of these proscriptions to argue against their constitutionality. Reviewing the application of the ban against “scandalous,” “disparaging” and “immoral” marks within the American trademark law, Professor Megan Carpenter emphasized that the lack of sufficient definitional standards forced trademark examiners to apply erratic explanations, often arriving at inconsistent results.27 Professor Alvaro Fernandez Mora reaches a similar conclusion in examining the European proscription against the registration of marks that are “contrary to public policy or accepted principles of morality.”28 Likewise, the Singaporean29 and Australian30 trademark regimes have been criticized for their ambiguity and lack of certainty.

In recent years, the inherent inconsistency of trademark provisions restricting disparaging, scandalous, and immoral marks has received substantial judicial and statutory attention. In 2017, in his concurrence in Matal v. Tam, Justice Kennedy explained how the bar against disparaging marks can be used to silence minority and dissenting opinions and is therefore violative of the free speech principles embodied in American constitutional jurisprudence.31 Building on its decision, in 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court reached a similar conclusion when reviewing the bar against scandalous and immoral marks.32 Across the Atlantic, the European Union (EU) has also struggled with the innate inconsistency in these provisions. The EU Intellectual Property Network developed a ‘Common Practice’ guide to enhance the consistency in the administration of morality-based restrictions on trademarks within the EU.33

These developments highlight the growing recognition that provisions restricting disparaging, scandalous, and immoral trademarks pose a potential threat to fundamental rights and that a more consistent and principled approach is needed in this area of intellectual property law. However, the first step towards delineating any such guidelines and examining morality-based proscriptions is understanding the administration of the provision and identifying the possible inconsistencies in its application. In a previous study, the authors commented on the lack of guidelines and consistency in the administration of morality-based proscriptions in India.34 This underscores the need for a comprehensive examination of these issues across different jurisdictions.

B. The lineage and interpretation of morality-based proscriptions in India

The legislative lineage of morality-based proscriptions in Indian Trademark Law can be traced back to the Trade Marks Act of 1940.35 Before 1940, trademark affairs in India were administered under the principles of English common law.36 Infringement matters were resolved in accordance with the Specific Relief Act of 1877, while registration procedures were overseen by the Registration Act of 1908.37

The history of the Act of 1940 is that of a Legal Transplant.38 It provides an interesting example of how a set of laws and legal doctrines were adopted by the recipient jurisdiction, in this case India, without according sufficient prominence to the unique cultural and social context.39 Adopted from the English Trade Marks Act, 1875, Section 8 of the Indian Trade Marks Act, 1940 prohibited the registration of trade marks which “consists of, or contains, any scandalous design,” or marks which were contrary to morality.40 However, one of the unique features of the law adopted in India was the explicit prohibition against registration of marks which are likely to hurt religious susceptibilities.41

The prohibition against the derogatory use of religious symbols draws its provenance from the unique socio-political situation of the Indo-British textile trade of the late 19th century. As textile mills from Great Britain and India ventured to explore new markets, their mill cloth was labelled with “ornate rectangular frame with an image from Indian mythology, or British Royalty.”42 As Indian mills started using similar labels, in 1877, the Bombay Mill Owners’ Association petitioned the government to introduce a trademark law in line with the Trade Marks Registration Act of 1875 introduced in England.43 When their petition was declined, the Bombay Mill Owners’ Association “defiantly decided to register the marks and labels of different mills in its own books, and resort to arbitration to resolve disputes.”44 The Mill Owners’ resolution incorporated a condition that names of gods and goddesses would not be registrable.45 In 1930s, when the deliberations for the creation of the Act of 1940 were initiated, a proposal was floated that the restriction imposed by the Bombay Mill Owners’ Association should be incorporated in the new legislation in an amended form.46 The resulting Act of 1940 included an explicit prohibition against the use of religious symbols which was “introduced to deal with local conditions.”47

Therefore, through the Act of 1940, the morality-based proscriptions adopted in Indian trademark laws were effectively split into three constituent parts: marks that contain scandalous designs, marks that are contrary to morality, and marks that can potentially hurt religious susceptibilities. Given the unique provenance and the legislative history of the bar in favour of religious susceptibilities, the present study is limited to examining the bar against scandalous marks and marks which are contrary to morality.

The Act of 1940 was replaced by the Trade and Merchandise Marks Act of 1958.48 It was enacted after a comprehensive review of the law of trademarks in India.49 Following the report submitted by the Justice Ayyangar Committee, an amending bill was introduced, and after a series of consultations and revisions,50 the Act of 1958 was enacted. In his report, Justice Ayyangar pointed out that the relevant English law, on which Section 8 in the Act of 1940 was modelled, had faced some judicial criticism.51 He suggested that Indian law should move away from English law and towards Australian trademark law, which, at the time, did not reference morality and only proscribed the registration of scandalous marks.52

The resulting provision was embodied in Section 11(c) of the Act of 1958 and prohibited the registration of marks that “comprises or contains scandalous and obscene matter.”53 The discussion of the transition from the Act of 1940 to the Act of 1958 clarifies that the morality-based proscription in Indian law was adopted from the Australian law, where the restriction is limited to scandalous marks.54 However, this discussion does not clarify how did the term “obscene” find mention in the Act of 1958. In a previous study, we have problematized the incorporation of the word “obscene” in India’s morality-based proscription.55 The Ayyangar Committee does not refer to a bar against “obscene” marks. After the Committee’s report was submitted, public consultations were conducted,56 and the resulting bill was also re-referred to a Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC).57 In the meticulous evidence submitted by the JPC,58 and the plethora of amendments suggested by them,59 no reference was made to the inclusion of a bar against marks containing obscene matter. Therefore, it remains unclear how the term ‘obscene’ finds reference in the Act of 1958.

Regardless of its provenance, the bar against scandalous and obscene marks continues to be a part of Indian Law. The Act of 1958 has since been replaced by the Trade Marks Act of 1999, which incorporates the bar against marks that “comprises or contains scandalous and obscene matter” in Section 9(2)(c).60

In the eight decades since the prohibition was incorporated into the Indian trademark law, it has suffered from an acute lack of judicial, administrative, and academic engagement. The only guiding instrument that can educate the interpretation of the provision comes from a draft manual (“the Manual”), published by the Controller General of Patents, Trade Marks and Designs (CGPTDM) in 2015.61

The Manual encapsulates the provisions and practices outlined in the Trade Marks Act of 1999 and Trade Marks Rules of 2017, presenting them along with the office procedures in a simplified and coherent manner.62 It functions as a general guide enumerating and explaining the practice of the Trade Marks Registry. However, the Manual suffers from multiple inconsistencies. Primarily, with the Act of 1958, the Indian law disavowed the language adopted from the English statute and removed the use of the term ‘morality’ from the consideration of morality-based proscriptions in India.63 In moving towards the Australian law, the Act of 1958 adopted the term ‘Scandal.’64 Since the term has been adopted from Australian law, it is only logical that its interpretation should also be educated by Australian law. However, that has not been the case. Since at least 1950, it is a well-established principle in Australian trademark law that consideration of ‘scandal’ does not allow a Trade Marks Examiner to engage with issues related to morality.65 Despite clear indication from the legislative history, the Manual maintains that, “Scandalous marks are those likely to offend accepted principles of morality.”66 This is only one example of the many inconsistencies in the Trade Marks Manual, which, as mentioned previously, is the only guidance in Indian law for interpreting the scope of Section 9(2)(c).67

In the following parts of the paper, the authors demonstrate how an absolute lack of definitional standards and guidelines for the administration of the provision has yielded erratic and inconsistent results.

II. Dataset

Publicly accessible bulk datasets of trademark application and registration information are crucial for enabling comprehensive, data-driven research on the administration of trademark law, including morality-based restrictions. Such datasets allow researchers to systematically examine trends, predictability, and potential biases in how trademark provisions are applied. In this section, we outline the dataset we developed in order to analyze morality-based restrictions in Indian trademark law. This section also emphasizes the importance of trademark offices making their data publicly available in a structured format, and will highlight valuable opportunities for research to better understand the practical implementation of trademark regulations.

In 2015, India’s Office of the Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks (CGPTDM) completed the digitization of their trade mark records.68 All the details of trade mark applications, including their prosecution history and current status, have been made available to the general public free of charge through IP India’s website.69 The first digitized entry on the register dates back to June 1, 1942, where the mark BLACK & WHITE was registered by the Trade Marks Office at Kolkata.70 Since 1942, the Registry has processed over 6.3 million applications, all of which have been digitized and are available on the CGPTDM’s website.

The website provides extensive data-points, including the original trade mark application, the examination report, opposition notices, and replies thereto, along with all the notices for Show Cause Hearings and all the office orders issued by the Registrar of Trade Marks.71 While the CGPTDM’s completion of this herculean task is commendable, the portals which provide access have been designed to cater only to the applicants and the professionals involved in the trade mark prosecution process. The CGPTDM has not created any bulk datasets from its digitized corpus of 6.2 million applications.

A. Existing Datasets in Other Countries and Possible Research Opportunities

Many other trademark offices across the world have adopted progressive measures by establishing and providing access to comprehensive bulk datasets, facilitating streamlined access to essential information and data points relevant to trademarks. Notable examples include the USPTO Trademark Case Files Dataset,72 the Canada Trademarks Dataset,73 and the Australian TM-Link Dataset.74 These datasets have emerged as invaluable resources for conducting extensive research, offering nuanced insights that have potentially reshaped the landscape of trademark laws on a global scale.75 Their accessibility and utility have played a pivotal role in advancing scholarly discourse and informing policy decisions.

The open availability of these datasets has kindled research along three major praxes.76 First, the information gathered from the datasets has been used to study the operation of economy. For example, Meindert Flikkema, Ard-Pieter De Man, and Carolina Castaldi examined a sample of 660 new Benelux trademarks to argue in favour of using the trademark data as an indicator of innovation for Small and Medium Enterprises.77 The authors suggested that trademark counts allow for a better measurement of service innovation and provide important information to measure the development and proliferation of technology-based innovation products.78 Valentine Millot also argued in favour of using trademark data as an indicator of non-technological innovation.79 She suggested that trademark data can provide important information to study innovation in service sectors.80

The second area where trademarks data can stimulate research is studying the branding and marketing strategies of firms. When companies aim to attract new customers and alter their market positioning, it can be beneficial for them to develop a new trademark.81 Moreover, establishing new trademarks can also motivate a company to focus more on marketing innovation.82 Alexander Krasnikov, Saurabh Mishra, and David Orozco suggested that trademarks can serve as indicators of firms’ efforts to build brand awareness and associations among consumers, which in turn mitigate cash flow variability and enhance financial value.83

Lastly, trademark data has been extensively used to study the operations and efficacies of trademark systems. In 2018, Beebe and Fromer analysed the Trademark Case Files Dataset published by the USPTO to study if fewer trademarks are available due to existing registrations and if an increasing number of applications seek to claim marks which have already been claimed by previous proprietors.84 They found that both of these trends have been increasing since the 1990s, and applications filed relatively recently favour complex, unique neologisms over standard English or common surnames.85 Their study concluded that “ecology of the trademark system is breaking down, with mounting barriers to entry, increasing consumer search costs, and an eroding public domain.”86 Von Graevenitz, Greenhaigh, Helmers, and Schautschick studied a similar trend in the European context. They employed the openly available datasets to examine if trademark registers contain “such a large number of unused and overly broad trade marks that the costs of creating and registering new marks substantially increase for other applicants.”87

Apart from issues related to congestion and cluttering, various other scholars have empirically examined issues related to trademark registration. Gerhardt and McClanahan studied how the involvement and quality of legal representation, compared to when an applicant proceeds pro se, impacted their success rate for registration.88 They identify that attorney-filed applications had a much higher chance of securing registration when compared to pro se applicants, especially in cases when the applications met with an Office action.89

In 2017, in Matal v. Tam, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the bar against disparaging marks violated the principles of the First Amendment and was therefore unconstitutional.90 In the wake of this decision, the scholarly community alluded to the possibility that the decision could result in the filing and registration of marks which disparage and besmirch minorities.91 However, empirical evidence suggests otherwise. First, Huang examined the data from the USPTO to identify trademark applications for racially-oriented marks and the effect of the Supreme Court’s ruling on these applications.92 Amongst a dataset of 4 million applications, she identified only 312 racially-oriented applications and concluded that there was no overall increase in the number of racially-oriented applications following the Supreme Court’s decision.93 Additionally, Goodyear extended this examination to queer trademarks and identified that while applications for queer trademarks had significantly increased, they were unanimously self-affirming.94

B. Building a Unique Dataset

Given the lack of comparable large-scale datasets, empirical scholarship relating to trademarks in India remains very scarce.95 This position is most critically visible in legal scholarship, empirically studying the functioning and efficacy of trademark systems in India. To fill this gap and contribute to the empirical literature examining trademark systems, we created a novel dataset by downloading and collecting examination reports from the online portal of the Trade Marks Registry. This exercise was conducted between October and December 2023, and 1.6 million applications filed between June 2018 and July 2022 were downloaded.96

After accumulating the examination reports, we auto-coded the dataset to identify the applications that received an objection under Section 9(2)(c) for containing scandalous or obscene content. This exercise identified 140 examination reports where any combination of the words ‘scandalous,’ ‘obscene,’ or ‘9(2)(c)’ was mentioned.

After identifying the applications, the authors hand-coded various important attributes of the applications including, the proprietor’s name, goods descriptions, and the trademark office where the application was filed. The applications were also classified between device marks and word marks.97 Amongst the 140 applications that received an objection under Section 9(2)(c), 91 applications were filed for securing registrations to device marks. To conduct a comparative analysis of the device marks, the authors used either the marks essential textual features98 or their textual depiction as presented in the trademark application.99 This exercise was conducted in February 2024, and any changes made to the applications after February have not been incorporated in the database.

The next section details some important trends and statistics which arise from the examination of the author’s novel dataset.

III. Descriptive Statistics

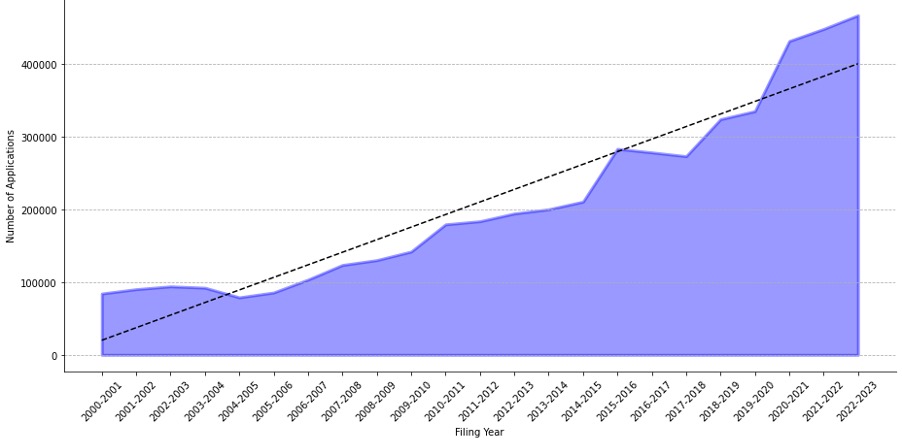

Figure 1 provides the overall context for the study. As per the data collected from the Annual Reports of the CGPTDM, since the turn of the century, the number of applications filed for registration has been consistently increasing at the rate of 8.66% annually. In the year 2000–01, 84,275 applications were filed for registration, and this number increased to 466,580 in 2022-23, effectively quintupling over the course of 22 years.

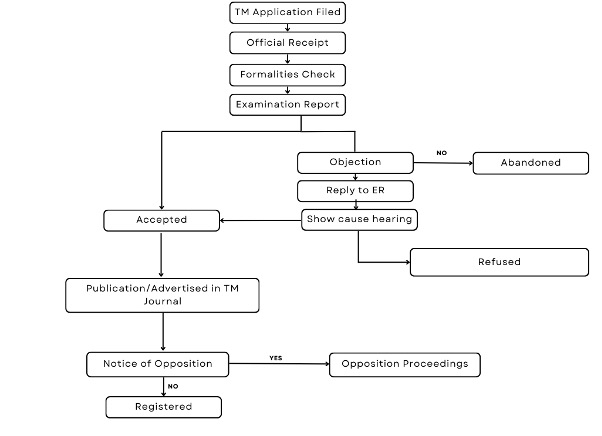

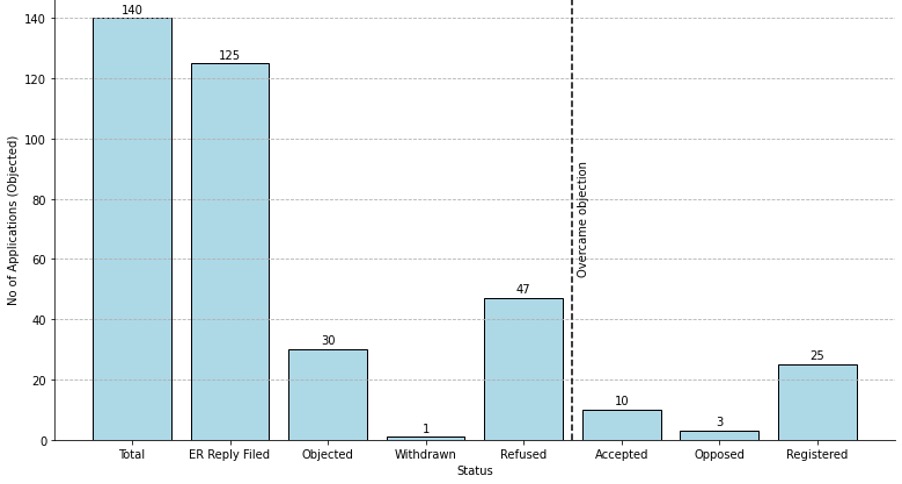

As discussed previously, the dataset for the present study encompasses the trademark applications filed between June 2018 and July 2022. Amongst the 1.6 million examination reports studied by the authors, only 140 applications were objected for containing scandalous or obscene matter, thereby attracting the mandate of Section 9(2)(c). Following the issuance of the Examination Report, the applicants are required to file a reply to the objections made in the Examination Report within 30 days. In case the applicant fails to provide a reply within the stipulated timeline, his application would be deemed abandoned due to non-prosecution.100 In the database examined for the present study, no replies were filed for 15 applications. Surprisingly, only 3 of these were officially designated as ‘Abandoned’ by the Registry. The remaining 12, although meeting the criteria for abandonment, did not receive formal abandonment orders.101

After a reply to the examination report is filed, if the Registrar of Trade Marks is not convinced with the submissions made therein, they can require the applicant to appear in a ‘Show Cause Hearing.’ During the hearing, an applicant is required to justify why their application should be allowed to proceed.102 Until such a hearing is completed, and the Registrar passes an order to the effect, the application is considered ‘Objected.’ Alternatively, applicants have the option to withdraw their application within 30 days of the Examination Report.103

After the reply to the Examination Report is filed and the Show Cause hearing is conducted, if the Registrar is satisfied with the submissions made therein, the objections are waived and the application is advertised in the Trade Marks Journal.104 Alternatively, if the Registrar is not convinced with the submissions made, the objections are sustained, and the application for registration is Refused. In the author’s dataset, an advertised mark is denoted ‘Accepted’ or ‘Accepted and Advertised,’ and if the application is refused, the status reflects ‘Refused.’ In the time period examined for the present study, only 1 application was withdrawn, 38 were accepted, 47 were refused and 30 are currently under objection, awaiting either acceptance or refusal.

Once a trademark is Accepted and Advertised in the Trade Marks Journal, the general public is invited to oppose the application within 4 months from the date of advertisement.105 During the time that an opposition is pending, the application status reflects ‘Opposed’ in the author’s dataset. If no oppositions are filed against the application, it proceeds to be ‘Registered.’ In the present dataset, 3 applications are going through opposition proceedings, while 25 have been registered. Figure 2 visually explains the prosecution process for a trademark application in India.

Figure 3 visualizes the progress of the applications that received an objection under Section 9(2)(c), through the trademark prosecution process. Amongst the 140 applications which were issued an objection under Section 9(2)(c), only 125 applicant filed responses to the objections raised in the Examination Report. Amongst the 125, 30 applications remain objected, and 1 has been withdrawn. In due time, the 30 applications currently under objections would either be Withdrawn, Refused or Accepted. For the remaining 95 applications, 47 were Refused, while 38 were Accepted. Amongst the 38 Accepted applications, 10 are open for Opposition, 3 have been Opposed and 25 have been Registered.

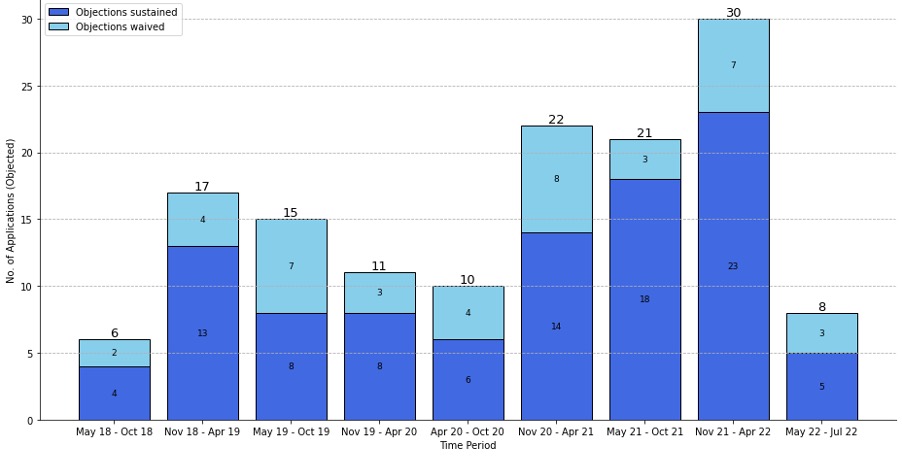

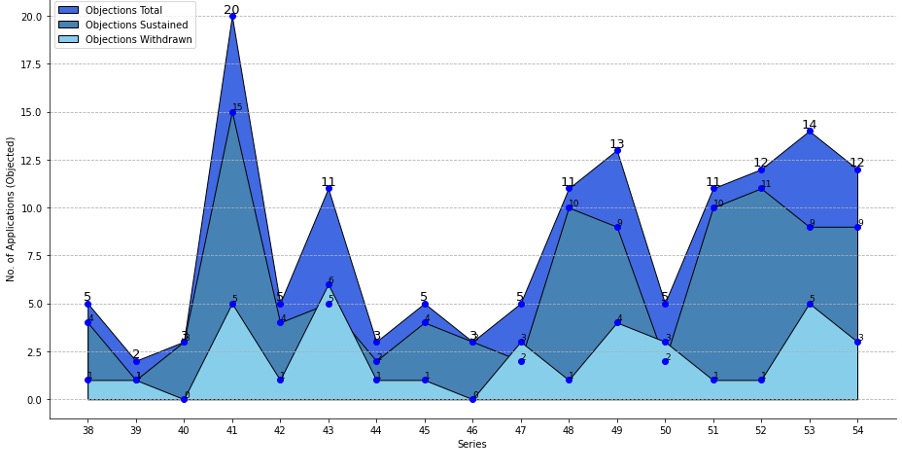

Figure 4 illustrates the number of applications that received an objection under Section 9(2)(c), presented alongside the applications that successfully overcame the objection. The tally for applications where objections were withdrawn only includes applications that were advertised in Trade Marks Journal after being objected under Section 9(2)(c) as of February 2024.

As has been shown in Figure 1, the number of applications filed each year has been steadily increasing. However, Figure 4 only represents the data on a bi-annual basis. It does not accommodate if there was an increase in the absolute number of objections which were issued during that period. Figure 5 has been included to address this and examines the number of objections issues, waived and sustained in intervals of 100,000 applications.106 It also analyzes how this rate varies depending on the time period in which the objections were raised.

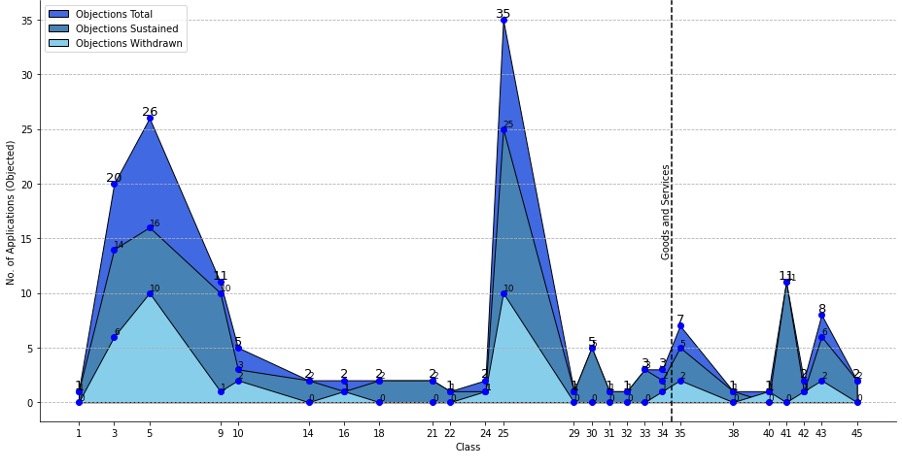

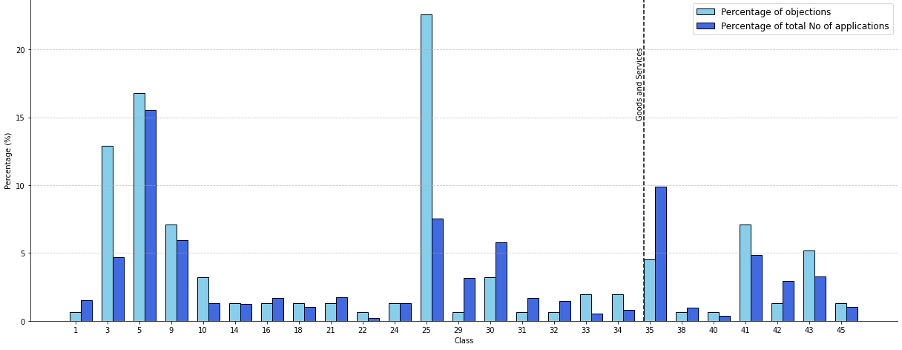

Figure 6 presents the total number of objections raised, withdrawn and sustained under Section 9(2)(c), across various trademark classes. It reveals a striking trend: objections under Section 9(2)(c) are predominantly concentrated in three classes. Class 3 (Bleaching Preparations), Class 5 (Pharmaceutical and Veterinary products), and Class 25 (Apparel Goods) collectively yield 76 objections, eclipsing 50% of all objections. Interestingly, classes pertaining to services yield fewer objections, amounting to only 29 objections, which is less than 20% of the total objections issues under Section 9(2)(c).107

The data presented in Figure 6 reveals some striking trends when compared to the total number of applications filed in each class. Out of the 1.6 million applications studied, only 120,367 were filed in Class 25 (Apparel Goods). Yet, these Class 25 applications account for 35 objections issued for containing scandalous or obscene content. This means that while Class 25 applications make up only 7.54% of the total applications, they are responsible for over 22% of the objections received under Section 9(2)(c). Similar trends can be witnessed in Class 3 (Bleaching Preparations), and Class 35 (Services for advertising and other office functions). Figure 7 further compares the percentage of applications filed in each class with the number of objections under Section 9(2)(c) within that class. These findings suggest disproportionately high rates of morality-based objections in certain trademark classes, warranting further investigation into potential reasons for such high proportions.

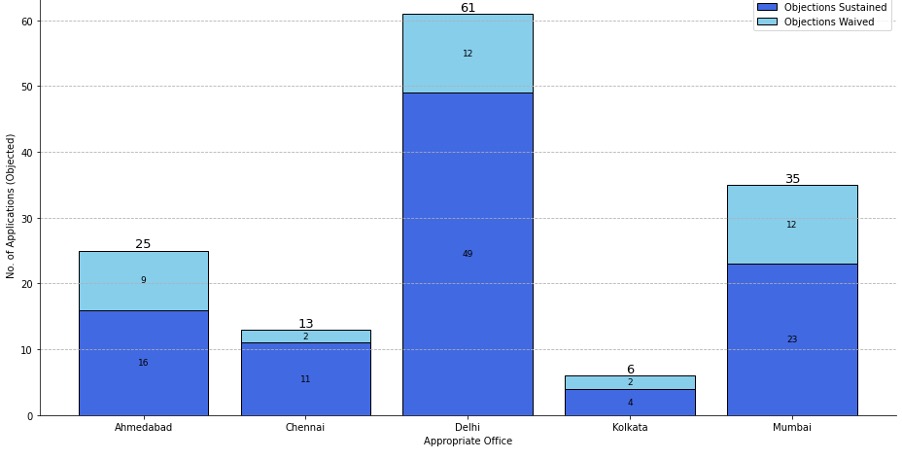

Figure 8 presents the total number of objections raised, withdrawn and sustained under Section 9(2)(c), across the different Trade Mark Offices.

The table shown below provides a comparison between the proportion of total objections issued by each office and the absolute number of applications submitted during May 2018 to July 2022 for prosecution before that office.

| Appropriate Office | Number of applications filed | Percentage of applications filed | Number of applications objected under 9(2)(c) | Percentage of objections issued under S. 9(2)(c) | Ahmedabad | 228,686 | 14.2% | 25 | 17.86% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chennai | 312,101 | 19.51% | 13 | 9.29% |

| Delhi | 591,517 | 36.97% | 61 | 43.57% |

| Mumbai | 369,445 | 23.09% | 35 | 25.00% |

IV. Trade Mark Registry’s Application of Section 9(2)(c)

As discussed in Part 1, in a previous study, we examined the scope and potential interpretation of Section 9(2)(c) by analyzing the jurisprudential lineage of the provision.108 The guidelines identified through the doctrinal study were then anecdotally tested by creating a purposive sample. This sample was generated by studying the existing literature to identify potentially scandalous and obscene terms. Using these terms, the authors conducted representative searches on the Trade Marks Register to observe how such potentially objectionable content was treated in practice.

This preliminary exploration provided valuable insights into the practical application of the morality-based restrictions outlined in Section 9(2)(c). Building on these earlier findings, this part presents a comprehensive, data-driven analysis of the administration of morality-based trademark objections, using author’s dataset.

To explain the findings in a cohesive manner, the authors adopt the methodology suggested by Beebe and Fromer. In a pioneering study published in 2019, Beebe and Fromer shed light on the administration of the morality-based proscriptions in the American Trademark Law.109 In order to provide evidence of inconsistency on the American Trademark Register, they provide three sets of evidence:110

- Instances where relative and absolute grounds for objection were used concurrently,

- Marks that successfully navigated morality-based objections by using vague grounds,

- Potentially scandalous or immoral marks that evaded objections altogether.

A. Combined Section 9(2)(c) and Section 11 objections

After an application for registration of a trade mark is submitted, it undergoes an examination process. During the examination process, a Trade Marks Examiner scrutinizes the application based on two key criteria: absolute and relative grounds. Absolute grounds, covered by Section 9, pertain to inherent qualities of a mark that may render it objectionable.111 For instance, Section 9(2)(c) prohibits the registration of marks that contain ‘scandalous’ or ‘obscene’ matter.112 On the other hand, relative grounds for refusal, governed by Section 11, are attracted when the potential registration of the mark could lead to confusion in the marketplace and encroach upon rights of other proprietors.113 Section 11(1) prevents the registration of mark which are similar or identical to pre-existing marks on the Trade Marks Register and are sought to be applied in reference to goods that are also similar or identical.114 Section 11(2) extends the extends this protection to well-known marks, even if applied to dissimilar goods.115

When an examination report combines Section 9(2)(c) and Section 11 to object to an application, it hints at a contradiction within the Registry’s decision-making process.116 By citing Section 9(2)(c), the Trade Marks Registrar objects to the presence of scandalous and obscene matter in the applied-for mark.117 By also invoking Section 11 and citing the existence of a similar registered mark, the Registrar implies an inconsistency. How can a mark, having navigated the prosecution process, be deemed confusingly similar to the applied-for mark potentially containing scandalous or obscene elements? This raises questions about the scrutiny applied during prosecution. Therefore, by its own admission, the Trade Marks Registry is administering Section 9(2)(c) in an inconsistent manner.

Between July 2018 and June 2022, the Trade Marks Registrar combined Section 9(2)(c) with Section 11 for 32 applications.118 Comparing this to American trademark practices, it highlights a concerning trend. In Beebe and Fromer’s research, out of 1901 instances where morality-based restrictions were applied, only 114 times were they combined with relative grounds for refusal, making up less than 0.6%.119 However, here, in the Indian context, this proportion increases to 2.2%.120

For instance, in March 2019, an application for registration of the mark CHOR BAZAR was filed in reference to services related to hotels and resorts (Class 43).121 Objecting to the registration of the mark under Section 9(2)(c), the Trade Marks Examiner suggested that the mark contains scandalous or obscene content.122 The Examiner also suggested that the applied-for mark was confusingly similar to a previous mark registered in Class 43, CHOR BIZARRE, and therefore the mark could not be registered.123 Interestingly, when the cited mark, CHOR BIZARRE, was examined in 2012, no objections under Section 9(2)(c) were raised.124

Similarly, the mark SAX VIDEO encountered an objection due to its alleged scandalous and obscene content when proposed to be used in reference to scientific instruments, electrical devices, computers, media, and fire extinguishers (Class 9).125 Additionally, it also faced objection under Section 11(1) for its perceived similarity to the registered mark SAX VIDEO PLAYER, used for computer software in Class 9.126 Notably, SAX VIDEO PLAYER underwent examination just 18 months prior to the applied-for mark and did not receive any objections for containing scandalous or obscene matter.127

In 2019, an application was made to register the mark NEUD XPOSE YOURSELF for pharmaceutical and veterinary preparations (Class 5).128 Despite opposing the mark for containing scandalous or obscene matter, the Examiner suggested that the mark was confusingly similar to a mark NUDE, which was already registered for a variety of healthcare goods (Class 5).129

Interestingly, the cited mark NUDE did not encounter objections for being scandalous when it underwent examination in 2008.130 However, since then, it has been used as a basis for objecting to the registration of numerous marks incorporating the word ‘NUDE’ in Class 5, such as NUDE HAIR,131 NUDE WHEY,132 and NUDEC.133 Such a usage of Section 9(2)(c) by the Registrar of Trade Marks raises important questions. First, NUDE was not deemed scandalous or obscene in 2007 but was considered so in 2019. Does this suggest a potential shift towards more stringent moral standards over time? Second, the registration of a potentially scandalous or obscene word in 2007 has led to the subsequent refusal of many similar marks in the same class under Section 11. This trend can potentially hint at congestion within the Trade Marks Register, a phenomenon also observed in the American Register by Beebe and Fromer.134

In addition to the three marks discussed earlier, there are another 29 instances within the 49-month period examined in this study where Section 9(2)(c) has been invoked alongside Section 11.135 Some noteworthy instances are discussed below:

- An applicant applied for the mark DICKS in reference beverage and food essentials (Class 30).136 Along with an objection under Section 9(2)(c), the examiner suggested that the mark was confusingly similar to an earlier mark, DEEKS, which was used in reference to bread & pastry assortment.137 The applications for the two marks were submitted with only a 25-month interval, and the application for DEEKS was passed without any objection under Section 9(2)(c).

- In March 2021, an applicant applied for a device mark, an essential feature of which was LAZYBUMS, for clothing and apparel.138 The Examiner objected that the mark contains scandalous and obscene content, while also citing another mark with an identical essential feature, LAZY BUM.139 The cited mark was examined only 4 months prior to the subject mark, yet the former was not objected to for containing scandalous or obscene matter.140

B. Applications that overcame an objection under Section 9(2)(c)

Once the reply to an Examination Report is submitted, and the Show Cause Hearing is conducted, if the Trade Marks Registrar is convinced by the submissions made by the applicant, his application is accepted and moves forward in the prosecution. Subsequently, it will be published in the Trade Marks Journal for public notification. A review of the various Replies to the Examination Reports filed by the applicants provides further evidence that the conduct of the Trade Marks Registrar is arbitrary and inconsistent in the administration of Section 9(2)(c).141

Amongst the 140 applications in the dataset that received an objection under Section 9(2)(c), only 38 applications managed to overcome the objection,142 while 47 applications were refused by the Registrar of Trade Marks. However, the criteria used by the Registrar to evaluate the responses from applicants defending their marks against objections under Section 9(2)(c) remain vague and erratic. This issue is further exacerbated by the fact that the orders issued by the Trade Marks Registrar are summaries in nature and do not provide any explanations as to the merit or content of the marks.

This ambiguity is most clearly exemplified in the prosecution record for the mark KISS MARY, which was applied for registration in the cosmetics and toiletry preparations category (Class 3) in March 2021.143 The Registrar of Trade Marks objected to its registration, citing the presence of scandalous and obscene material.144 However, in the applicant’s response, they failed to address this specific objection. The only objection highlighted in the Examination Report pertained to Section 9(2)(c). The Registrar did not make any references to Section 11, and no confusingly similar marks were cited in the Examination Report. Despite the only objection relating to absolute grounds, the reply mischaracterized the objection and defended the mark against the cited marks in the examination report, even though no such marks were cited by the Registrar. The applicant failed to defend against any objections related to Section 9, let alone Section 9(2)(c) specifically. Despite the erroneous Reply, the Registrar accepted the application on January 24, 2024, and it was advertised in the Trade Marks Journal on February 5, 2024.145

Within the cohort of 47 applications, a recurring theme emerges concerning objections under Section 9(2)(c). Applicants frequently resort to invoking the distinctiveness of their mark. However, this strategy does not consistently sway the Registrar’s decision, leading to inconsistencies in the application process.

For example, in March 2019, an applicant applied for the mark NUDES for providing services as an Architectural Firm (Class 42).146 The Registrar cited Section 9(2)(c) and objected to the mark for containing scandalous or obscene content.147 The applicant defended the mark by claiming that the mark was a coined and invented term, which had no reference to the services offered under the mark. These submissions should have no bearing on whether the mark contains scandalous or obscene matter. Regardless, the mark was accepted by the Registrar and was published in the Trade Marks Journal.148 Similar ambiguity is apparent in the cases of various other marks, such as HORNI, which was applied for registration concerning medicinal and pharmaceutical preparations (Class 5),149 CEX,150 BOOBS & BUDS,151 and RIBALD THE NEECH,152 all of which were applied for registration relating to clothing and apparel (Class 25).

Conversely, appeals to distinctiveness have remained unsuccessful in many cases. For example, in March 2021, an applicant applied for the registration of the mark NUDE ROMANCE, to be used in reference to non-medicated cosmetics and toiletry preparations (Class 3).153 When the application was objected to for containing scandalous or obscene content, the applicant invoked the inherent distinctiveness of the mark, claiming that the mark was a coined term and did not bear any inherent connection to or meaning for the goods in reference to which it was adopted.154 However, the Registrar was not convinced by the applicant’s submissions and the application was refused.155

Identical treatment has been afforded to various other marks. In April 2019, an applicant applied for the registration of three marks, FUCK CHARDONNAY,156 FUCK MERLOT157 and FUCK CABERNET,158 in reference to alcoholic preparations. All three applications were objected to for containing scandalous or obscene content. In their reply, the applicant appealed to the inherent and applied distinctiveness of the marks. The Registrar refused to waive the objections and held that:

[T]he content of the mark being “FUCK” means have sexual intercourse with (someone). I found this content of mark scandalous. The applicant failed to overcome the objections under section 9(2) (c) raised in the examination report, hence, refused.159

Similarly, when the registration for the mark SANSKARI SEX was objected to for containing scandalous or obscene content, the applicant appealed to the inherently distinctive nature of the mark.160 However, the Registrar refused the application and held that “[t]he applicant submitted that the applied mark is coined, innovative, unique combination and distinctive. It does not designate any characteristics of the applied services. Therefore, prayed for acceptance of the mark. However, the applied mark consists of obscene or scandalous matters which is prohibited u/s 9(2)(c) of the Trade Marks Act,1999. Hence, refused.”161

The analysis of the dataset reveals that appeals to the distinctiveness of a mark represent just one approach among many that applicants employ in responding to objections under Section 9(2)(c). The outcomes are inconsistent—for some marks, such appeals to distinctiveness were sufficient for the Trademark Registrar to overcome the morality-based objection, while in other cases, they were not successful. This suggests that the standards and decision-making criteria used by the Registrar to evaluate responses to Section 9(2)(c) objections remain unclear and unpredictable. The lack of a consistent, reasoned approach undermines the transparency and fairness of the trademark registration process.

C. Applications for potentially Scandalous and Obscene marks that never received an objection under Section 9(2)(c)

The inconsistency in the conduct of the Trade Marks Registry is not limited to waiver of objections, it also extends to the issuance of objections. For applications filed between June 2018 and July 2022, the Trade Marks Registry did not issue objections under Section 9(2)(c) to significant number of applications that, based on the Registry’s own standards, should have been considered immoral and scandalous. In order to identify such applications, the authors studied the Trade Marks Journal to identify applications which were similar to the marks intercepted by the Registry for containing scandalous and obscene content.

For example, in November 2018, an applicant applied for registration of the mark NAKED AND RAW COFFEE FACE WASH in reference to cosmetics and toiletries (Class 3).162 The Mumbai Trade Marks Office opposed the registration of the mark under Section 9(2)(c).163 However, when the same applicant applied for the marks NAKED & RAW COFFEE FACE SCRUB164 and NAKED & RAW COFFEE BODY SCRUB165 in the same class before the same office, no objections under Section 9(2)(c) were raised. There was only a difference of seven days between the publication of the examination report for the first mark and the remaining two. In fact, the same applicant also applied for the mark NAKED AND RAW in Class 3 before the Mumbai Trade Marks Office, and the mark proceeded to registration without any objection under Section 9(2)(c).166 Furthermore, there are many other marks with the constituent word NAKED already registered in Class 3, including NAKED TRUTH BY MYGLAMM,167 NAKED URBAN DECAY,168 and NAKED SKIN.169 None of these marks received any objections for containing scandalous or obscene content.

A similar case can be highlighted in reference to Tobacco Products in Class 34. An applicant applied for two device marks, the essential textual elements of which were HASH170 and HASH LIGHTS.171 Both marks were filed before the Delhi Office and were examined within a 16-month interval. Yet while the second mark was objected for containing scandalous and obscene content,172 the first mark received no such objection.173 This was also noted by the applicant in his Reply to the Examination Report for the second mark.174

Such a treatment can also be witnessed when the applied-for marks contain non-English words. In March 2019, the mark CHOR BAZAR, was applied in reference to providing services related to hotels, resorts, etc. (Class 43).175 The Chennai Trade Marks Office objected the mark under Section 9(2)(c).176 Interestingly, not only did the Registrar suggest that the mark was confusingly similar to a previously existing mark, CHOR BIZAREE,177 they also omitted to consider the fact that there were various other marks registered in the same class which did not receive an objection for containing scandalous and obscene content. Some of these marks are MAAKHAN CHOR,178 BIRYANI CHOR179 and KAAMCHOR.180

One of the clearest enunciations of the inconsistency in administration of Section 9(2)(c) can be witnessed by studying marks where a composite component is the word SEXY. For example, between June 2018 and July 2022, the Registrar of Trade Marks objected four marks with the constituent word SEXY: I’MSEXY,181 JUSTSXY,182 FEEL SEXY WITH POP CULTURE,183 and SEXY BRA.184 Within this time period, there were five other applications which passed the examination stage without being objected under Section 9(2)(c): SEXYBEAST,185 SEXYBUST,186 SEXYFISH,187 PLAY SEXY,188 and LA SENZA 24 SEXY.189

Another trend that can be witnessed relates to moral paternalism and how it affects the decisions made by Trade Marks Examiners. In January 2021, an application for registration of the mark ONE DOLLAR SEX CLUB was filed before the Delhi Trade Marks Office in reference to dating and matchmaking services under Class 9 and 45.190 The concerned examiner issued an objection under Section 9(2)(c), suggesting that the mark contained scandalous and obscene matter.191 The decision of the Registrar is difficult to reconcile with the fact that there are many marks in Class 45 which include the constituent word SEX. Some examples include, SSS STOP SEX SLAVERY, applied in reference to “providing social services in relation to prevention of human slavery and exploitation,”192 PROJECT SAMVAAD: CREATING A SAFE SPACE FOR SEXUAL AND SOCIO-EMOTIONAL WELLBEING,193 and SAFE SEX WEEK194 applied for providing legal, personal and social services.

The varying treatment of marks within the same class suggests that Trade Marks Examiners base their moral standards on the specific goods and services associated with the mark. Such a nuanced approach is important for determining morality-based proscriptions in trademark law.195 However, it is important that any discretion awarded to the Trade Marks Examiners is constrained by broad guidelines and principles for its determination. As highlighted in the previous study, such guidelines are completely absent as is evidenced by the conduct of the Trade Marks Registry. Such discretion can lead to inconsistent results. As the present dataset reveals, only 25% of the applications that received an objection under Section 9(2)(c) successfully navigated the objections. The remaining 36% remain stuck in the objection process, while 32% were refused. Therefore, an office objection under Section 9(2)(c) poses a significant barrier to registration of a trademark and needs to be administered consistently and methodologically.

V. Discussion and Conclusion

The examination of morality-based proscriptions in trademark law, both internationally and within the Indian context, highlights the complexities and inconsistencies inherent in such regulations. The previous study conducted by the authors revealed the lack of clear definitional and guiding standards to govern the application Section 9(2)(c) of the Indian Trade Marks Act 1999.196 By creating and leveraging a novel dataset, this study provides empirical evidence of the inconsistencies in the administration of the provision. While these complexities are innate to the nature of morality-based provisions, acknowledging their existence is the crucial first step towards mitigating them.

While engaging with this issue, it should be noted that trademark laws assimilate a complex paradox. On the one hand, it regulates commercial expression, and it is aimed at improving market efficiencies and reducing consumer search costs. On the other hand, trademarks can become powerful expressions of political, social, and expressive speech.197 Professor Katyal suggests that this complexity arises because of trademark law’s inherent conflict between two metaphors: the marketplace of goods and the marketplace of ideas.198 While the marketplace of goods is premised on fixed nature of property rights, the marketplace of ideas is premised on dynamism and fluidity.199 Thus, trademarks can have a fixed meaning for use in trade but also an expressive meaning which is fluid, and can take on different meanings.

This dynamism is best explained by reference to one of the trademark applications intercepted by the authors’ dataset. In February 2022, Isha Yadav, a doctoral student from a public university in India, applied for the trademark MUSEUM OF RAPE THREATS AND SEXISM.200 She applied the mark in reference to training, education, entertainment and cultural services. Possibly because the word “rape” forms part of the trademark, the Registry cited an objection under Section 9(2)(c).201 However, a basic search of the context in which the mark is applied reveals that Ms. Yadav has been engaged in memorializing and documenting instances of violence against women in digital formats.202 In one of her social media posts, she explains her project and says:

I’m looking for women who’ve received sexist comments, misogynist slurs, rape threats or unsolicited genitalia, or have been violated and harassed on any social media platforms, either in comment sections or inboxes.

I’m collecting these screenshots and curating a digital installation, where I’m creating a digital collage of *all the shit womxn go through*, online, only for being themselves.

I hope to memorialise the verbal violence, visualize the effect of this violence, and explore the sense of solidarities among women and this part of our lives. The exhibitions serves as a space of intervention into the ideas of consent, coercion, harassment, and assault. I invite views to engage with the act of violation, power politics, and the inflicted trauma of verbal violence, and tethered sense of agency, through the medium of screenshots in the installation.203

Ms. Yadav’s case serves as the prototypical example of the inherent conflict in trademark law. The remit of her mark is not limited to its commercial function, it embodies a powerful social and political comment. Despite its potentiality, the mark is now stuck in an administrative tussle, and, as the present study would imply, she has only a 27% chance of navigating this tussle successfully.