Alexandra J. Roberts *

Download a PDF version of this article here.

I. Dupe Culture

Dupe culture is having a moment. From major players like Walmart and Glade using the term to describe their products in online ads, to “dupe influencers” posting viral videos on TikTok, to savvy shoppers building dupe-focused communities on Reddit, dupes dominate sales and searches.1 Seventy-one percent of Gen Z and sixty-seven percent of Millennials report that they sometimes or always buy dupes.2 Where older generations clandestinely purchased dupes hoping to pass them off as the real thing, young bargain-hunters eschew gatekeeping and proudly share their finds with friends and followers. But even as many advertisers and influencers embrace the term, Amazon has banned its use,3 TikTok has blocked the hashtag #designerdupe,4 and Target’s legal team forbids the company from saying the word.5 This Article interrogates the multiple meanings of “dupe” and sets out to answer the question, is dupe advertising ever false advertising?

“Dupe” has no single definition because it’s used differently by different contingents.6 As a shortened form of “duplicate,” meaning “a copy,” the noun has been in circulation since the early 1900s.7 “Dupe” also has another denotation, one not irrelevant to this discussion—it refers to a person who has been misled, a “victim of deception.”8 Use of the term has increased dramatically in the past five years:9 Google searches for “dupe” rose 40% from 2021 to 2022;10 the hashtag #dupe racked up 6.3 billion views on TikTok in 2023 alone.11 Keyword searches for “dupe” combined with a brand or product name have skyrocketed across social media platforms12 and retail sites like Amazon,13 eBay,14 and Temu.15 The Oxford English Dictionary,16 Google Ngram,17 Google Trends,18 and Law36019 all confirm the word’s speedy ascension.

In some circles of the Internet, a dupe is a more affordable version of an unattainably expensive product.20 I’ll call those “pure dupes.” A dupe in the beauty industry might be a lipstick in the same shade as that of a luxury label, a serum that uses the same ingredients as a high-end one, an affordable version of an expensive haircare tool, or a discount-brand shampoo that positions itself as equivalent to a fancier one. “Dupe” is also used widely to describe a perfume that mimics the scent, but not the packaging, of a more expensive perfume.21 In fashion, a dupe might be a shoe, dress, or handbag that fits the same description as the one from a prestige brand worn by celebrities or featured in magazines—and could even pass for the real deal if you squint—but the dupe only recreates the item’s look, not its logo or insignia.22 Fast fashion retailers like Asos, Zara, and Shein diligently feed consumers’ appetite for dupes, churning out lower-priced copies of high-end brands’ products at remarkable speed.23 Some discount chain stores, such as Walmart and Aldi, engage in similar practices.24

But dupes aren’t limited to makeup and beauty, though those categories receive the most attention. “Dupe” is versatile. Over-the-counter drugs have been characterized as dupes, as have generic or compounded versions of prescription drugs and devices.25 In electronics and home goods, shoppers seek out dupes for brand-name speakers, blenders, and couches. Dupes regularly go viral; demand for specific dupes can even overtake demand for the original.26 And while some decry dupes’ existence even when they’re perfectly legal, others argue that copying spurs competition27 and that interest in a dupe increases the allure of the real thing, benefiting the “duped” brand by leading consumers to perceive it as even more elite and desirable.28

A dupe isn’t always a legitimate, lower-priced substitute. For another set of users, a dupe is quite simply a counterfeit.29 Counterfeits replicate well-known brands’ registered trademarks or logos, as when someone other than Chanel sells a handbag featuring the brand’s famous interlocking “C’s.”30 Reports have noted a rise in the use of the term, related hashtags, and assorted intentional misspellings to help shoppers find counterfeits and work around filters; on some sites, “dupe” picked up where similar code words like “knockoff,” “AAA,” “mirror quality,” and “reps” left off.31 Some consider this use of “dupe” a co-opting of the term:32 a well-known fashion law blog explains that “dupe” was “traditionally used to refer to legally above-board products that take inspiration from other, existing (and often much more expensive) products,” but “the new use of ‘dupe’ refers to products that make unauthorized use of brands’ names and other legally-protected trademarks, meaning that they are not [true dupes] but trademark infringing and/or counterfeit goods.”33 The American Apparel and Footwear Association has taken an emphatic stand against dupe influencers, accusing them of “facilitating the sale of unauthorized and counterfeit goods…partak[ing] in illicit activity and potentially becom[ing] accessories in the trafficking of illegal counterfeits.”34 And two recent law review articles treat “dupe” as synonymous with “counterfeit.”35 Dupe influencers who sell counterfeits have become increasingly creative, shipping out lookalikes with separate logo stickers or patches for buyers to attach at home or using hidden links to advertise products on one platform and route followers to another to purchase them.36 “Infringing dupes,” dupes that knowingly infringe design patents, utility patents, copyright, trademark, trade dress, or trade secret protection, fall into an adjacent and overlapping category.37

Of course, there is plenty of gray area between “dupes” as counterfeit or infringing goods and “dupes” as affordable alternatives to high-end products. Some dupe producers aspire to get as close as they can not only to the product, but also to its name, appearance, and packaging, without actually infringing. I’ll call those “risky dupes.” Australian cosmetics company MCoBeauty, for example, is known for “openly pushing legal boundaries to duplicate trending, higher-end cosmetics, selling them at major retail outlets for a much lower price.”38 The company publicly embraces duping as a “pillar” of its marketing strategy.39 While its stated goal is to stay on the non-infringing side of the line, MCoBeauty has been sued several times for infringement and opted to settle those suits.40 Arguably, though, its strategy is similar to the less risky “store brand” approach with which American consumers are already quite familiar.41 A grocery chain might offer shampoo in a bottle designed to mimic that of Herbal Essences, position the shampoo next to Herbal Essences on its shelves, and include text like “compare to ingredients in Herbal Essences”; they might even name their version something similar yet distinguishable, like “Organic Essence.” United States courts have typically treated such comparative marketing—positioning a product as a house brand alternative to another and using packaging cues to make the reference obvious—as acceptable if it doesn’t create a likelihood of consumer confusion.42

Risky dupes are risky, therefore, precisely because it’s difficult to predict with certainty that they will not be found infringing. While counterfeits that copy the brand name and logo of luxury goods tend to be recognizable as counterfeits to sellers and buyers alike, infringing products may be less readily identifiable as infringing.43 In the fashion industry in particular, some forms of intellectual property protection can be hard to come by or take too long to obtain to be practically useful,44 so copyists may assume brands lack enforceable rights in the products they dupe. Where a fabric print is protected under copyright, the shape of a sneaker under design patent, the formula for a face serum under utility patent or trade secret, or the overall appearance of a hairspray bottle under trade dress, the duper may be unaware of that protection. Whether or not protection exists can be difficult for dupe producers and dupe advertisers to ascertain, especially when it comes to trade dress, which is less likely to be registered than word marks or logos—meaning competitors are not on notice of trade dress owners’ real or perceived rights. And whether a court would find infringement of any form of intellectual property is notoriously difficult to predict.45 Intent may play a role in assessing infringement in some jurisdictions,46 but it’s not the only element that matters, and courts differ on how they interpret the role of intent when a brand tried to copy a product but was not trying to pass their copy off as authorized or confuse consumers. (Meanwhile, when it comes to false advertising—discussed further below—several circuits have rejected the idea of intent to deceive having any role to play at all.)47

Lastly, in this continuum of dupes, we have “scam dupes.” According to one study, nearly half of consumers consider themselves to have been “scammed” when they purchased a viral dupe product on social media.48 Of those, 38% said the item wasn’t of the quality shown or described; 26% reported that the item arrived damaged; 24% said it never arrived at all; 14% reported an allergic reaction to it; and 9% said they had to seek medical treatment after they used it.49 Some accounts report sellers using photos or videos of someone else’s product to market their own.50 Whether or not a dupe is infringing or counterfeit, it may simply be so low quality as to constitute a scam; in some cases, it may not even exist.

So “dupe” contradicts itself; it is large, it contains multitudes.51 The spectrum of dupes includes a) “pure” dupes: lower-priced, distinctively-branded and non-infringing alternatives to luxury or high-priced goods; b) “risky” dupes: lower-priced alternatives that aren’t as clearly non-infringing; c) “infringing” dupes: products that infringe another producer’s intellectual property; d) “counterfeit” dupes, products that use other producers’ registered trademarks or logos; and e) “scam” dupes: egregiously poor-quality goods, goods that don’t come close to matching their advertised description, or goods that never actually ship to purchasers. The categories overlap, of course, and a dupe can fall into more than one category at the same time—a dupe might be counterfeit and a scam, for example, or counterfeit and infringing. An apparently pure dupe might also be risky.

The consequences of advertising and selling counterfeit, infringing, and risky dupes are fairly straightforward: producers and in some cases advertisers should be aware that IP owners may enforce their rights against those sellers by suing, sending cease and desist letters, or availing themselves of platform-specific takedown procedures. Law enforcement might pursue criminal counterfeiting charges;52 FTC or state attorneys general might attempt to shut down a business for defrauding consumers.53 For scam dupes, the appropriate cause of action might be breach of contract, breach of express or implied warranty, or false advertising independent of the use of the term “dupe.”

This Article mostly sets aside issues of infringement and counterfeiting to focus on one specific question: is the simple fact that something is marketed as a “dupe” ever, in itself, enough to constitute false or deceptive advertising? While it may be uncontroversial to claim that marketing counterfeit, infringing, risky, and scam dupes as “dupes” for well-known products can be deceptive, I argue that even sellers of pure dupes might be vulnerable to false advertising claims if the products are simply too different to merit the label “dupe.”

II. Dupe Users

Who actually uses the term “dupe”? It isn’t just influencers, though their use of the term has surged in recent years, especially on platforms like TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube.54 Consumers use the term and hashtag to seek out alternatives for products they can’t afford or for which they simply prefer to pay less, building entire communities around various categories of dupes. Reddit, which saw a 50% rise in the creation of dupe-focused communities on its site from 2022 to 2023,55 is rife with examples, but so are specialty sites like What to Expect (a platform for expecting parents)56 and dupe.com (a search engine for furniture dupes).57 Google search data from the trend forecaster Spate found online searches for “dupe + skin care” increased 123.5 percent in a single year.58 Traffic on Dupeshop, a platform that compares beauty dupes against their more expensive counterparts, has increased more than 100 percent year over year and boasts more than a million users.59 Journalists and bloggers write reviews, rankings, and recommendations for dupes, with headlines like “35 Cheap Product Dupes That Are Just As Good As The Real Thing,”60 “The Best Designer Dupes of 2023 and Where to Buy Them: Gucci, Cartier,”61 and “Splurge or Save? Sephora Collection Dupes for High-End Favorites.”62 Fashion and entertainment magazines like Us Weekly63 and InStyle64 also recommend products as “dupes” for others, as they have long done by other names before the term “dupe” came into vogue. And speaking of vogue, Teen Vogue uses the tag “dupes” to collect its copious dupe coverage in one place.65

In addition to all those third-party uses, major companies have turned to “purposeful duping,” making dupe claims in their marketing materials.66 Whole Foods67 and Walmart68 have used “dupe” in advertisements, whether sincerely or tongue in cheek.69 Some companies are not shy about plastering their websites with the word—like perfume brand Aromapassions, whose second-level domain names include “dupe” and whose homepage proclaims in large font that visitors to the site can “buy perfume dupes online.”70 Makeup brand Lottie London seeks out and reposts influencers’ dupe videos that feature its products and use hashtags like #dupe and #fentydupe.71 And air freshener brand Glade launched its own “dupe detector,” where users are invited to upload a photo of a candle they like so the app can recommend a Glade product with a similar scent as a substitute.72

Some companies, though, eschew the term even when they’ve built their business model around the concept. Dossier, which sells dupes of designer perfumes and boasted 10,342% growth in just three years, avoids saying “dupe” altogether, instead relying heavily on the term “impressions” to describe their smell-alike fragrances. A spokesperson explains that it’s “[n]ot because we’re embarrassed about what we’re doing. Not at all. We’re very proud of it…It’s more that we were fearing that it might have a negative connotation and more importantly, we wanted to be known for high quality.”73

But most of all, it is influencers who are consistently credited with, or alternately blamed for, the meteoric rise of dupe culture. Some have built their personal brand as dupe experts and accrued hundreds of thousands of followers by shilling dupe recommendations across product categories. Influencers are “social media personalities paid to leverage their popularity to market products and shape consumer preferences.”74 Anyone who promotes a product online in exchange for something—whether that thing is money, commission, free stuff, or any other benefit that might affect the weight consumers give their endorsement—is engaged in influencer marketing.75 Researchers have found that influencers have a “profound impact” on consumers’ purchasing intentions and stimulate demand for the products they endorse.76 In the more traditional version of this model, a brand might connect with an established social media influencer and negotiate a deal in which the influencer promotes the brand’s products on one or more social media platforms, such as a flat payment for a set of posts or a pay scale that rewards posts on different platforms at different rates. Some brands might send a product to a group of influencers and ask them all to post about it in the same week. Many brands supply the influencer with guidance, such as keywords to use and product attributes to highlight.77

But influencer marketing takes many forms. Influencers, especially dupe influencers, increasingly engage in affiliate marketing rather than contracting directly with brands. In affiliate marketing, an influencer receives a cut of the profit when the content they post results in a sale,78 with sales typically tracked through affiliate links that consumers click to purchase the product or codes that shoppers enter at checkout. In some cases, the influencer is posting at the behest of the brand and may have negotiated their rate. But platforms like LIKEtoKNOW.it (often abbreviated LTKit) and programs like TikTok Shop, Instagram Shopping, and Amazon Storefront have cut out the middleman, making it possible for influencers to endorse products and earn income without being specifically selected by brands as ambassadors.79 While traditional fashion and beauty influencers may occasionally post about dupes, dupe influencers are likely to design their entire persona around informing followers about dupe products—whatever that term means to them—with account names like @thedupesyouneed_80 and @dupethat.81 Given the range of referents for “dupe,” that means some dupe influencers are operating entirely above-board in recommending alternative, lower-cost products in a niche like fashion or beauty, while others deal primarily in counterfeits.

It also means some influencers are unknowingly endorsing infringing products or making deceptive claims, which may be riskier than they realize given that it’s possible—if unlikely—for them to be liable for false or misleading advertising82 as well as direct or contributory infringement.83 Whether an influencer is hired directly by a brand, uses affiliate links independently, or does not earn money at all when they post about dupes has implications for liability, as does any guidance they receive from the brand they’re endorsing. An influencer who posts about dupes for fun, not profit, or monetizes their account with an embedded advertising model like the one YouTube uses for successful channels rather than tying profits to specific endorsements or sales, is less likely to be liable for deceptive claims or infringement. An influencer who uses an affiliate model or sells their own goods or services is engaging in advertising and may be liable under state or federal law;84 the nature of their posts may also bring them under a separate set of platform-specific rules for advertisers that don’t apply to users sharing finds for free.

And when an influencer contracts with a brand to endorse their products, both the influencer and the brand may be liable if the influencer violates the law. For example, haircare brand L’Oréal hired twin influencers Makenzie and Malia to post on TikTok about the brand’s Olaplex dupe,85 a relationship the twins disclosed in compliance with FTC guidance using the hashtag #LorealParisPartner. If aspects of their message, which includes “Dupe alert” and “I’m talkin’ $33 versus $90,”86 were deemed deceptive, both L’Oréal and the twins could be held accountable.87

III. Dupe Advertising Law

False advertising is prohibited by a number of different laws, including the federal Lanham Act, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Act, and state consumer protection or deceptive practices statutes and common law prohibitions.88 False advertising also violates the terms of service of most social media platforms.89 Section 43(a)(1)(B) of the Lanham Act prohibits false or misleading statements about a company’s own goods or services or those of another party that are likely to deceive consumers, affect their purchasing decision, and harm the complaining party in some way, such as through reduced sales or reputational damage.90 Companies have standing to sue under the Lanham Act; consumers do not.91 The FTC Act, meanwhile, prohibits unfair or deceptive acts or practices in commerce as part of FTC’s consumer protection mandate.92 The Commission can bring administrative complaints or federal lawsuits, issue cease and desist orders, enjoin deceptive practices, mandate corrective advertising or disclosures, and impose penalties such as disgorgement and restitution.93 And consumer protection laws in every state prohibit deceptive commercial practices; in most states both consumers and attorneys general or other state agencies are empowered to sue violators to enforce those prohibitions.94

FTC also issues additional guidance construing the FTC Act, including guidance specific to individuals and brands engaging in influencer marketing, a form of endorsement.95 According to its “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials,” endorsements must be truthful and nonmisleading and reflect the honest opinions of the endorser,96 and an endorser must have been a bona fide user of the product advertised when an ad represents them to be.97 Endorsers’ claims also require substantiation, just as an advertiser’s own claims do.98 And individuals who receive a material benefit for endorsing a product or brand that might affect the weight or credibility of their endorsement must clearly disclose that fact.99 A material benefit can include getting paid to post about a product, receiving a percentage of sales through an affiliate agreement, owning a stake in the business whose products the influencer endorses, or receiving free products or services.100 Both advertisers and endorsers are liable for false or unsubstantiated statements made by endorsers, as well as for endorsers’ failure to disclose that content is sponsored.101 So while some advertisers seem to view influencer marketing as a loophole that enables them to disseminate false claims or disguise advertisements as organic content, FTC guidance and other advertising regulations belie that view. While dupe influencers are more likely to engage in affiliate marketing directly through a platform like LTK.it or Amazon storefront, as discussed above, they are still included as endorsers under FTC’s definitions and bound by the same guidance.102 Influencer marketing can be particularly insidious because it filters advertising claims through individuals whose followers feel they know and trust them, and whose recommendations those followers view as authentic and sincere.103 Those features make application of false advertising laws in the influencer marketing context crucial to avoid deception.

Comparative advertising—comparing one’s products or services to those of another—is legal as long as it isn’t false or deceptive.104 In fact, according to one practical guide, about a third of all advertising in the US is comparative, and studies show that comparative ad claims “produce[] greater attention and message recall” than noncomparative claims.”105 FTC has defined comparative advertising as “advertising that compares alternative brands on objectively measurable attributes or price, and identifies the alternative brand by name, illustration or other distinctive information.”106 Comparative claims can include superiority claims, which assert a product is better than those of competitors, and parity claims, which assert that a product is at least equal to those of competitors.107 And advertisers are entitled to use competitors’ trademarks in advertising, calling the products or brands out by name, as long as they satisfy the principles of nominative fair use.108 Under nominative fair use doctrine, advertisers are free to compare their products to those of competitors—including calling out those competitors by name—and explain why consumers should choose theirs, with slogans like “produce as fresh as Whole Foods, at half the price” or “if you like Ray-Ban, you’ll LOVE Rayex.”

Those references to others’ products do not just benefit the advertisers—they benefit consumers too, providing information and benchmarks that shoppers often find useful in making a purchasing decision. Comparative advertising may be particularly crucial to sellers of products like eyeshadow, perfume, and food; as one treatise author points out, “colors, scents, and flavors…cannot be described verbally; they can only be compared to something the consumer already knows.”109 FTC has officially come out in support of comparative advertising, which it deems “a source of important information to consumers [that] assists them in making rational purchase decisions,…encourages product improvement and innovation, and can lead to lower prices in the marketplace.”110 The Commission is therefore committed to “scrutinize carefully” attempts to restrain the use of comparative advertising given its benefits.111

But that commitment comes with caveats.112 FTC supports brand comparisons where the advertiser identifies the basis of comparison, such as price or performance. Comparative claims, like all advertising claims, must be truthful and non-deceptive, and comparative advertising in particular “requires clarity.”113 The McCarthy treatise reminds, “[e]ven if a seller uses a competitor’s mark in comparative advertising so as not to cause a likelihood of confusion of affiliation, but the claims of comparison with other goods are not true, there can be liability for false advertising or trade disparagement.”114 Professors Tushnet and Goldman, in their advertising law casebook, note that parity claims can only be proven false by showing that the comparator is superior,”115 i.e. that the advertised product is not as good as, as effective as, or as liked as the product to which the ad compares it. “Nonetheless,” they continue, “products need not be identical to be compared. If the basis of comparison is sensible in light of consumer uses of a product or service, then comparison is legitimate even though other types of comparisons are also possible.”116

When assessing whether an advertising claim is false or misleading, factfinders place claims into one of several categories. A claim can only be a statement of fact if it’s capable of being proven true or false.117 Claims that are too general, vague, subjective, or exaggerated to be understood as factual are known as “puffery.” A slogan like “Better ingredients. Better pizza” for a restaurant chain falls into this category: whether one set of ingredients or brand of pizza is better or worse is a subjective assertion, and different consumers are likely to reach different conclusions.118 Likewise, a claim that a brand of pasta is “America’s Favorite Pasta” constitutes mere opinion, rather than a statement of fact that could be adjudged true or false.119 And when a cable company ran ads showing pixelated images to represent the clarity of a competitor’s picture, the court ruled those images puffery rather than false visual claims because they were so exaggerated that no reasonable consumer would take them seriously.120 Advertising law is centered on consumer perception. So if we surveyed consumers, we might find that any reasonable shopper who saw a post touting a $12 Shein boot as a dupe for a $2,000.00 Chanel boot would consider the comparison mere puffery, too exaggerated and unlikely a proposition to convey any real or measurable equivalence between the shoes besides the basic fact that both are, well, shoes. But if every claim calling something a dupe is mere puffery, how do we end up with nearly half of the consumers surveyed reporting they felt scammed or disappointed by a dupe?121

If an advertising claim is not puffery, it might be deemed literally false, false by necessary implication, or misleading. Claims communicated through visual representations, including photographs, images, and videos, can qualify as false or misleading claims.122 Most jurisdictions and FTC divide literally false claims into two categories: efficacy claims, which are general claims that a product is effective or does what it’s supposed to do, and establishment claims, which reference data or studies in support of their veracity. Courts typically interpret a prima facie Section 43(a)(1)(B) case to require that an actionable claim be 1) false or misleading; 2) affecting interstate commerce; 3) in advertising or promotion; 4) deceptive; 5) material, i.e. affecting the purchasing decision; and 6) injurious.123 Most courts presume deceptiveness when a claim is literally false, and some also presume materiality; otherwise, or when a claim is deemed merely misleading, deceptiveness and materiality can be proved using consumer surveys. FTC takes a similar approach; it also considers not only what the claim affirmatively communicates but also whether it fails by omission to reveal any material facts.124 State laws vary, with some defining false advertising explicitly and others incorporating FTC’s definitions.125

Of course, heterogeneity in meaning will always exist—the same claim in the same advertisement will be interpreted differently by different consumers based on their experience, expectations, trust in the source, and other factors. For survey evidence to be useful, courts need to establish some benchmarks to determine how many deceived consumers is enough to enjoin a claim. Courts have grappled with the same question in trademark law: how many consumers must find a mark famous, generic, inherently distinctive, or confusingly similar to another mark for an owner to earn or lose protection or succeed in enforcing their rights against another party? While there are no concrete answers to that question, courts considering survey evidence in a likelihood of confusion analysis generally agree that “a competent survey showing that the number of deceived consumers is ‘not insignificant’ will be sufficient proof of confusion.”126 Some consider 15% the key threshold for a survey to weigh toward infringement. 127

In Section 43(a)(1)(B) cases, when courts presume a literally false claim is deceptive and material, actual consumer perception is less likely to influence the outcome. Where a claim is impliedly false or merely misleading, though, courts rely heavily on surveys, and tend to apply a similar “not insignificant” or “not insubstantial” standard to the one they use in infringement cases.128 Survey evidence is usually not necessary in FTC and Better Business Bureau’s National Advertising Division (NAD) cases—both agencies consider themselves sufficiently expert to judge how a claim will be perceived—but it may still be helpful.129 Courts construing both the FTC Act and the Lanham Act have held that where the false claim is likely to cause very serious harm or involve human safety, smaller percentages of deceived consumers may suffice to support the claim.130

As an alternative to courts, some companies take their false advertising complaints to NAD. NAD applies federal false advertising law as well as some principles derived from FTC guidance131 in its non-binding dispute resolution process. Companies with gripes against competitors’ advertising find the NAD appealing because its process is streamlined, efficient, and far less expensive than federal litigation, and most companies whose ad claims are challenged voluntarily comply with NAD’s recommendations—perhaps because if they decline, NAD refers the dispute to FTC. NAD also conducts its own monitoring of advertising claims and independently initiates about a quarter of the cases it hears.132

In determining whether an advertising claim is false, factfinders must first construe the meaning of the claim.133 Few courts have taken up the question of how to interpret a claim that one product is a dupe of another.134 But dupe advertising is a form of comparative advertising, which is a genre courts have certainly seen before. Claims like “compare [product being advertised] to [other leading product]” or “if you like [competitor brand], you’ll love [advertiser’s brand]” are far from new.135 The Eighth Circuit in one such like/love case held that an advertiser “does not commit unfair competition merely because it refers to another’s product by name in order to win over customers interested in a lower cost copy of that product if the reference is truthful” and non-confusing.136 A federal court applying state law reached the same conclusion where an advertiser used the phrase “If You Like Estee Lauder…You’ll Love Beauty USA.”137 Likewise, the Second Circuit had no problem with hang tags that described the garments they hung from as copies of Dior originals, holding that the law “does not prohibit a commercial rival’s truthfully denominating his goods a copy of a design in the public domain, though he uses the name of the designer to do so.”138

But the details matter. Courts have held that while comparative claims communicate a mere invitation to compare in some cases, in others they may convey, “depending on their wording and context,…a specific assertion of measurable fact, such as the same ingredients or efficacy.”139 Factfinders in some cases have therefore deemed “like/love,”140 “alternative to,”141 “compare to,” or “our version of” advertising claims to communicate a factual representation of equivalence or a claim requiring substantiation. In one case, perfume brand Shalimar contended that another brand’s claims that its product was “like” or “similar to” Shalimar and that “if you like [Shalimar] then you’ll love [Fragrance S]” were false. The district court had granted summary judgment to the advertiser, relying only on the court’s own sniff test in determining that the fragrances were indeed similar, but made clear that if they had not been, it would be possible to find the comparison “false, misleading, or fraudulent.”142 The Ninth Circuit, pointing to expert affidavits concluding that the products differed in chemical composition, fragrance, and longevity,143 reversed the district court, finding a genuine issue of material fact remained on the similarity question and therefore on whether the advertiser’s comparative claims constituted false representations.144 In a different perfume case, the court deemed packaging that called copycat perfumes “our version of” better-known scents deceptive because that language “impl[ied] that the products are similar, if not equivalent,” when they were actually neither.145

Meanwhile, in a district court case, a manufacturer of dietary and nutritional supplements called Body Solutions sued a competitor, alleging that its use of the phrase “Compare to Body Solutions” on labels constituted a false or misleading claim because it suggested that the two products were identical, substantially similar, or equally effective.146 While the advertiser tried to paint its comparative claim as puffery, the court disagreed, stating that the “invitation to ‘compare’ does not qualify as a vague claim of superiority. Unlike more subjective terms often used in advertising, ‘compare’ suggests that a product’s performance has in fact been tested and verified.”147 And in another case, a district court considered sunglasses sold with a label inviting consumers to compare its prices to another brand and concluded that the label was misleading in that it either suggested that the products were similar in quality or that they were affiliated.148 Because the lens quality was totally dissimilar and the companies were not affiliated, the court deemed the comparison misleading.149 In other words, the court held that an invitation to compare a low-end copycat with the high-end product it copied communicated more than simply “both brands sell sunglasses, and Deziner’s sunglasses cost less.” Instead, it conveyed some equivalence between the products—one the court found did not exist.150 In the Dior hangtag case mentioned above, the court only declined to enjoin the comparison to the luxury brand because it was “apparently truthful,” clarifying “[w]e do not understand plaintiffs to claim that the garments were so poorly made or executed as not to constitute copies.” Some dupes, as we know, are so poorly made as not to constitute copies151—so to the extent that the line of cases allowing comparative claims rests on truthful comparison, it will not always apply if dupe claims are challenged.

It bears noting, though, that many of the Lanham Act cases that have explored the possible deceptiveness of comparative advertising claims are at heart trademark or trade dress infringement cases that also allege unfair competition, free-riding, or false advertising; their likelihood of confusion and false advertising analyses can be difficult to disentangle completely.152 The NAD considers only advertising claims, so its assessments are not intertwined with trademark ones. According to NAD, “the determination as to whether a ‘compare to’ claim is a comparative performance claim or merely an ‘invitation’ to compare the products in question depends on the context in which the ‘compare to’ claim appears in the challenged advertising.”153 That context can include factors like the product’s positioning as a house brand offering154 or the proximity of the “compare to” claim to more objective efficacy claims like, in the case of shoe inserts billed as similar to Dr. Scholl’s, “Superior Comfort” and “Helps Reduce Impact Forces.” In several cases, NAD has deemed “compare to” claims simply invitations to compare two products without making parity or comparative performance claims that require substantiation.155 But in one of those cases, NAD rested its conclusion in part on the fact that a real basis for comparison did exist, “unlike an advertiser that seeks to deceptively ‘upgrade’ its product by comparing it to a completely dissimilar and superior product.”156 And in a handful of other decisions, NAD recommended that advertisers discontinue use of “compare to” claims, finding they could leave reasonable consumers under the impression that the brands being compared “are similar in type, composition and efficacy”157 when no substantiation for those claims had been provided.

FTC does not appear thus far to have taken specific action against dupe influencers or issued guidance about the use of the term “dupe.” But it seems inevitable that some dupe influencers violate its Guides. First, a study found that most influencers engaged in affiliate marketing on YouTube and Pinterest fail to disclose that they derive a material benefit from those posts.158 That failure may be even more deceptive than it is when traditional influencers do it, because it’s more difficult for followers to spot that an influencer’s posts are advertisements when they are not shilling for a well-known brand. Second, influencers can be liable under the FTC Act for false or misleading claims, just like traditional advertisers can; if comparative claims can be construed as making representations about quality, materials, or product features, which Lanham Act and NAD precedent indicates they can, then claims that one product is a dupe for another may well be deemed false. And finally, an endorser must be a bona fide user sharing their true opinion. Some dupe influencers have explained that they use features like reverse image searching to locate dupes to share with their followers.159 Whether the dupe is a couch or a lipstick, an influencer who doesn’t own and use it or hasn’t at least tried it out violates this aspect of FTC guidance.

While this discussion focuses primarily on US advertising law and US cases, dupe advertising takes place—and reaches consumers—worldwide. As in other aspects of advertising regulation, some countries have more restrictive laws about comparative advertising than does the US.160 A number of civil law regimes prohibit or previously prohibited comparative advertising completely, some on the view that even non-confusing comparative advertising necessarily involves one brand free-riding on the goodwill of another.161 In the European Union, the Misleading and Comparative Advertising Directive lists the conditions under which comparative advertising is permitted, including where “it does not present goods or services as imitations or replicas of goods or services bearing a protected trade mark or trade name.”162 That means that even in the absence of confusion or deception, an advertiser can face liability for advertising something as an imitation or replica of a branded good. In one case applying that provision, a company advertised smell-alike perfumes, using similar packaging to the branded version and providing retailers with a comparison list matching the branded perfumes with the advertiser’s own version.163 The UK court that initially heard the case concluded that the advertiser’s use of the other perfume trademarks violated the law by taking unfair advantage of the reputation of the brands it copied, even though neither retailers nor consumers were deceived.164 The Court of Appeal of England and Wales referred several questions to the European Court of Justice (ECJ).165 The ECJ agreed with the lower court and further construed the Directive to say that goods or services fall within the meaning of the provision whether presented as imitations or replicas explicitly or implicitly.166 The ECJ’s decision suggests that a term like “dupe” that indicates a product is a duplicate of or substitute for another likely also exceeds the bounds of acceptable comparative advertising in the EU. Nonetheless, the case has its critics;167 several scholars read the “imitations or replicas” directive as essentially banning comparative advertising.168

While a few brands are engaging directly in dupe culture, as discussed above, many are watching from the sidelines, scrutinizing references to their brands to determine whether the term signals an infringing product or deceptive claim or merely acceptable comparative advertising or puffery. A number of lawsuits have mentioned or included evidence of use of the term “dupe.” Some cite a defendant’s products being described as a dupe as evidence of actual confusion, as when American Eagle sued Walmart over jeans that it claimed infringed its distinctive trade dress.169 Others cite the “dupe” label as proof of intentional copying, as when handbag brand Cult Gaia sought to enjoin Steve Madden’s production and sale of a bag it deemed an unauthorized copy of its Ark Bag.170 One company included the detail in its utility patent infringement complaint, noting “Beauty writers, influencers, and customers refer to KISS’s copycat Falscara as a ‘dupe’ of Lashify’s system.”171 Another included use of the label in its copyright infringement complaint, suggesting that “consumers and commentators” calling Old Navy items “dupes” of Lilly Pulitzer items was proof of their “striking” similarity.172 And others, perhaps unsurprisingly, cite the use of “dupe” in reference to products that resemble theirs in general support of their trade dress or trademark infringement claims.173

Finally, and most relevant to this discussion, several brands have included evidence of the use of “dupe” or “duplicate” in connection with false advertising claims. Vans, in its suit against Primark alleging trademark infringement and federal false advertising, notes that “Primark’s influencers compare the Infringing Products to Vans authentic products and refer to and promote the Infringing Products as…‘duplicate’ Vans.”174 Haircare brand It’s a 10, in a suit against a manufacturer of lookalike products alleging trade dress infringement, federal false advertising, and violation of Florida’s Deceptive Practices Act, highlights consumer reviews on Amazon calling defendant’s product a “drugstore dupe for It’s a 10 Miracle Leave-In” and “a total dupe” for its product.175 Amazon accused two popular influencer accounts of federal false advertising and violation of Washington’s consumer protection law when they promoted their products as “dupes” as part of a “sophisticated campaign of false advertising for the purpose of evading Amazon’s counterfeit detection tools.”176 And while Lashify has sued one competitor for allegedly marketing dupes, a second competitor, Urban Dollz, has sued Lashify for false advertising based on claims by the company and its agents that Urban Dollz’ DIY lash system “is a ‘dupe’ of [Lashify’s] system.”177 In the suit, Urban Dollz seeks an order prohibiting Lashify from “engaging in false advertising under the Lanham Act, including by making false statements…accusing [Urban Dollz] of being a…dupe.”178

Most recently, Williams-Sonoma Inc. (WSI), whose portfolio includes furniture brands Pottery Barn and West Elm as well as Williams-Sonoma, sued dupe.com, a website and browser extension that enables consumers to use reverse image searching to find alternatives to high-end furniture, which the defendant labels “dupes.”179 WSI alleges numerous kinds of false claims by the defendant, including accusing West Elm of “scam[ming]” consumers by selling for “over $2,000.00” a chair when the defendant claims “the same chair” is available for 80–90% less from other sellers. In reality, according to the complaint, the West Elm chair costs significantly less; most importantly, “the same chair” cannot be available from other retailers because it is exclusively designed and manufactured for WSI.180 According to the complaint, while the website purports to help consumers find dupes, i.e. it “claims that its search tool returns [products] that are ‘the same’ or very similar to the products that users query, Dupe.com searches routinely return results that are materially different from the original product in appearance, material, size, dimensions, and/or quality.”181 By owning and operating a website named for dupes, with which it claims users can locate dupes for their desired furniture items and through which it advertises, showcases, and receives commissions on the sale of those so-called dupes, defendant allegedly engages in false advertising and unfair competition under the Lanham Act and state law.182

IV. Duped by Dupes

A recent study found 49% of consumers surveyed considered themselves to have been “scammed” when they purchased a viral dupe product on social media.183 Is that simply the consequence that purchasers risk when they choose to buy a dupe to save money, rather than splurge on the desired item from the well-known brand—play stupid games, win stupid prizes? In fact, doesn’t this consumer experience demonstrate exactly why big brands invest so heavily in their trademarks and reputations: so consumers know a product is high quality and its producer stands behind it? And if a product arrives damaged, doesn’t arrive at all, or harms the buyer, isn’t that simply a breach of warranty, and perhaps deceptive advertising by the seller unrelated to their use of the term “dupe”? Maybe. But maybe there’s more to explore here. With as many as half of consumers feeling swindled, it’s worth asking what the use of the term “dupe” actually conveys in an advertisement and whether and when it might constitute false advertising.

Take, for example, the $600 Dyson Airwrap, a hair multistyler that comes with six attachments and promises to dry, curl, straighten, smooth, volumize, and more—reportedly one of the products consumers most frequently search for in combination with the term “dupe.”184 Websites from Business Insider to TechRadar have reviewed and ranked Airwrap dupes.185 If a competitor or paid influencer advertises a “Dyson Airwrap dupe” that’s only equipped with half as many features as the real thing, is billing the product as a dupe a false claim? What if the dupe is known to cause burns because it reaches a much higher temperature than the Airwrap does? What if the dupe is simply poor quality—not fit to replace anyone’s standard hair dryer, curler, or flatiron, so not worth even its meager price? Does the comparison to the Airwrap inherent in calling it a “dupe” convey some equivalence, or is it just a way to grab attention without making any factual claims?

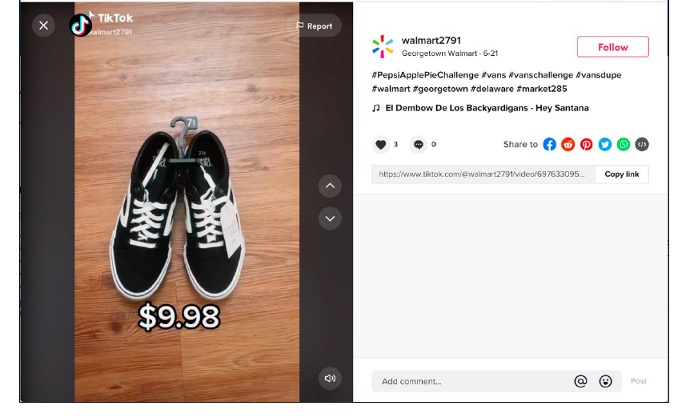

Or consider a pair of Vans, sought after as skate shoes due in part to a thick and sticky rubber sole that provides maximum grip on a skateboard and makes the shoes more durable. Now imagine Walmart’s “Van dupes” have a plastic sole that makes them ill-equipped for skateboarding. The image below shows a post on TikTok from a Walmart store advertising Vans lookalike sneakers with the hashtag #vansdupe. Has Walmart misled consumers by characterizing their shoes as dupes for the skate shoes if they don’t share those basic features with real Vans?

Now think of a beauty product like Eve Hansen Hydrating Hyaluronic Acid Serum, which sells for one-seventeenth the price of a $220 cult favorite from SkinMedica. If the Eve Hansen product is advertised as a dupe, but turns out to contain different ingredients than the SkinMedica product and as a result irritates users with sensitive skin, should the advertiser bear some responsibility for positioning the products as equivalents? Dupes have also taken off in the perfume market, as the advent of gas chromatography analysis enables producers to reverse-engineer a fragrance by identifying and quantifying its ingredients.186 Does that ability increase the likelihood that a consumer will assume they can trust a product marketed as a dupe for their desired perfume? If a seller uses the term “dupe” for a fragrance with different ingredients in different quantities, does that context render their characterization deceptive?

Answering these questions requires drilling down on not only what kinds of representations courts have construed to constitute false or deceptive comparative advertising, but also what “dupe” means to consumers. And as discussed in Section I, “dupe” doesn’t mean just one thing—from counterfeit dupes to risky dupes to pure dupes, it can mean different things to different people, sometimes at the same time. Just as with other categories of comparative advertising, such as “like/love” claims, “compare to __” claims, and the use of similar trade dress to convey equivalence, context is crucial. Consumer surveys will be needed to ascertain what consumers take away from a dupe claim, and perception will be shaped by how the claim is framed, what products are being compared, and who the relevant purchasers are.187

Conclusion

The public has a compelling interest in the information function of advertising and in producers communicating to consumers the existence of alternatives to dominant brands. This principle underlies both nominative fair use doctrine and FTC’s policy in favor of comparative advertising. As the Ninth Circuit articulated in Smith v. Chanel back in 1968, “[t]he presence of irrational consumer allegiances may constitute an effective barrier to entry. Consumer allegiances built over the years with intensive advertising…extend substantial protection to firms already in the market.”188 Comparative advertising is the best way to challenge those firmly entrenched allegiances.

What’s more, copying existing products in ways that do not infringe intellectual property rights is in the public interest;189 muzzling producers from advertising with reference to the brands they copied would undermine the ability to communicate those options to consumers, “bar[ring] effective communication of claims of equivalence”190 and inhibiting the free flow of commerce.191 Comparative marketing, and in particular dupe marketing, offers brands that are newer, smaller, or simply less famous the ability to cut through the noise and reach consumers (directly or through intermediaries) with their messages about affordable alternatives.192 Seeking out dupes using search features on social media and shopping sites and following dupe influencers grants savvy shoppers access to products and services that better fit their budget and serve their goals and that they might not otherwise discover. And dupe influencers have incentive to avoid deceiving their followers, given their value derives from their reputation, reliability, and recommendations.

Maybe all’s fair in love, war, and dupe marketing. How can someone be surprised when their $11 dupe Airpods from Temu lack many of the features of their $250 Apple ones,193 or their $12 Gucci loafer dupes from an Amazon shop with an unpronounceable name aren’t made of real leather?194 Calling something a dupe is a form of comparative advertising. Comparative advertising, as the case law illustrates, is all fine and good—until it’s not. Amazon has outlawed dupe marketing for a reason, and consumers’ widespread disappointment indicates that in some cases, characterizing something as a dupe is over-promising. While many ads calling a product a dupe of another are non-deceptive and noninfringing, there are likely some that don’t bear scrutiny. When a product infringes, use of the term “dupe” can exacerbate the confusion and qualify as unfair competition or false advertising. And even when a product itself does not violate any laws, promoting it as a dupe might be false or misleading if consumers understand the term as a representation that the item possesses certain qualities or features or is comparable in quality to the original.

Litigation citing use of the term “dupe” is already pending195 and more will likely follow. Courts should seek to understand what consumers perceive the term to mean in the specific context of the ad in question. Brands, influencers, and consumers should also proceed with caution and awareness of the risks of dupe marketing and dupe purchasing. Given the desirability and utility of characterizing products as dupes, the European approach—holding that explicitly advertising something as an imitation is inherently unfair—goes too far. But expecting consumers to sort through dupe advertising claims to parse what “dupe” conveys in every new situation may be unduly burdensome. Future litigation will have to reckon with the question of what consumers perceive the term to convey in a particular context from a particular speaker. For now, even sophisticated consumers may be made dupes by dupes.