With the rise of AI image generators, even an artistically untalented law student like myself can depict nearly anything imaginable within minutes. By typing “Mario eating a slice of pizza in Washington Square Park, watercolor” into Dall-E, I can quickly conjure an image of Nintendo’s iconic character reenacting my post-class lunch from last Tuesday.

This seemingly new image exists at the convergence of my imagination, a vast database of billions of existing images, and a complex algorithm that, after being trained on these images, assembles new art by recognizing patterns and blending elements of the database. But as you look at Mario enjoying his slice, several copyright law questions should naturally come to mind. Is this truly a new image? Or is it a copy, pieced together from other images? And does this image violate the copyright rights of the artists whose works contributed to the dataset? These very issues are at the heart of Andersen v. Stability AI, a landmark lawsuit from the Northern District of California concerning the copyright implications of AI-generated art.

Background

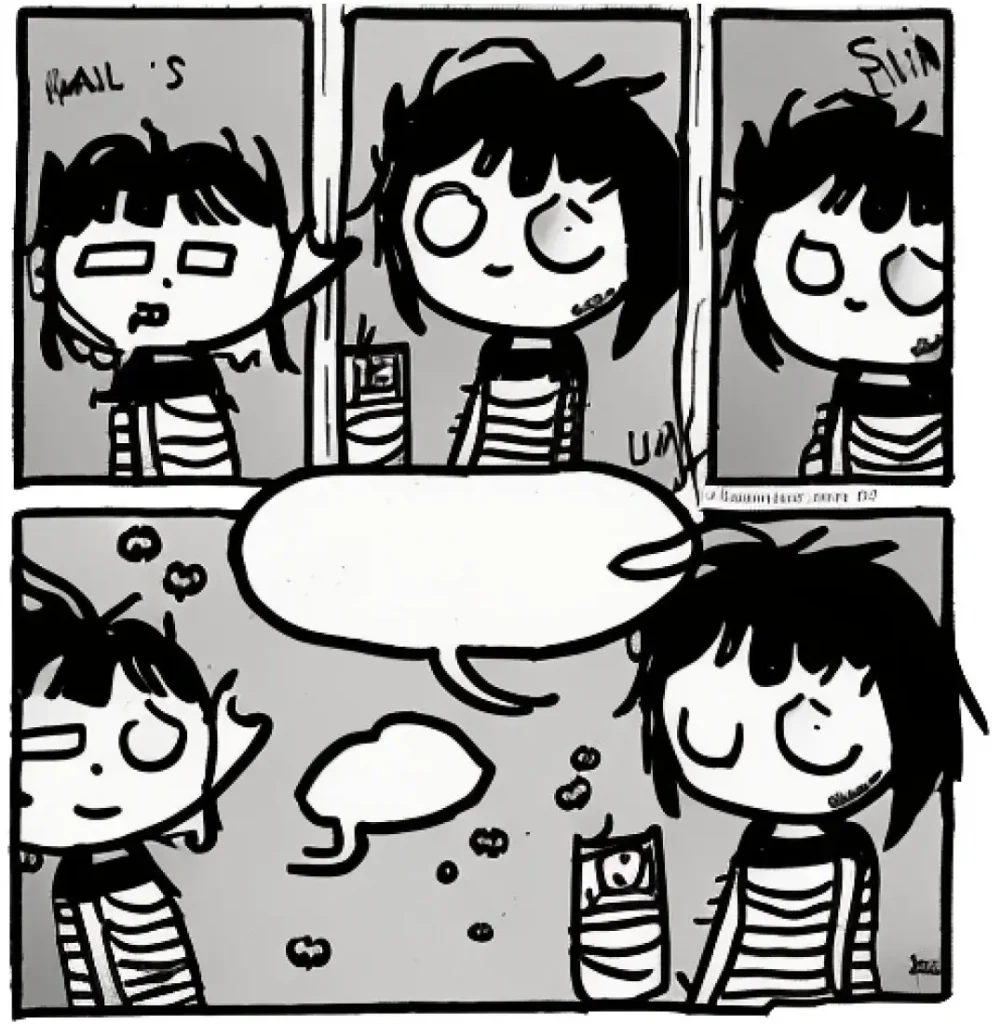

In late 2022, popular internet cartoonist Sarah Andersen penned a New York Times guest essay titled “The Alt-Right Manipulated My Comic. Then A.I. Claimed It,” where she shared her experience of having her art misappropriated, first by far-right online groups and later by AI tools trained on her art. In the essay, she recounted that simply using her name as a prompt on AI image generator “Stable Diffusion” generated new images in her distinct artistic style. While the recreations of her comics weren’t perfect, they had the signature elements of her comics, leading her to write, “I see a monster forming,” regarding the potential threat of image generators to the livelihoods of artists like herself.

On January 12, 2023, Andersen, along with several other artists, acted on these concerns and filed a class-action copyright infringement lawsuit against several AI companies (Stability AI, Midjourney, DeviantArt) in federal court. While there had been prior lawsuits by copyright owners against AI developers, this case was among the first where creatives united to challenge the use of their works for AI training, with many similar cases following shortly after. The lawsuit focuses on the LAION data set, which consists of 5 billion images that were scraped from the internet and used by Stability AI and other companies to develop their AI image generators. Among other legal claims, the complaint accuses said companies of copyright infringement for including the plaintiffs’ work in the dataset to train AI systems, allowing the case to serve as a precedent-setting moment in the ongoing legal battle between artists and AI companies.

Artists Recently Scored a Major Win

While several of the plaintiffs’ many claims, such as unjust enrichment and breach of contract, have been dismissed by the Northern District of California Court, the artists recently secured a significant win with an August 12th ruling. Here, U.S. District Judge William Orrick denied Stability AI and MidJourney’s motion to dismiss the artists’ copyright infringement claims, allowing the case to move towards discovery.

In reaching this decision, the judge found both direct and induced copyright infringement claims to be plausible. The induced infringement claim against Stability AI argued that by distributing their model “Stable Diffusion” to other AI providers, the company facilitated the copying of copyrighted material. In allowing this claim to proceed, the judge noted a statement by Stability’s CEO, who claimed that Stability compressed 100,000 gigabytes of images into a two gigabyte file that could “recreate” any of those images. The judge also pointed to the plaintiffs’ presentation of academic papers demonstrating that training images could be reproduced as outputs from AI products by using precise prompts.

As for direct infringement claims against Stability AI and others, Judge Orrick found the plaintiffs’ model theory, which argues that the AI product itself constitutes an infringing copy because it embodies the transformations of the plaintiffs’ works, and distribution theory, which asserted that distributing the AI product is equivalent to distributing their copyrighted works, to both be plausible. When moving these claims forward, Judge Orrick noted that these theories depended on whether the plaintiffs’ protected works were found within the AI systems in some form and would be addressed again at the summary judgment stage.

Going Forward

With Judge Orrick’s August 12th decision, Andersen v. Stability AI will move into the discovery stage with the trial set to begin on September 8, 2026. This ruling opens the door to a deeper examination of how AI companies use copyrighted works to train their systems and whether these practices violate existing copyright laws. If the plaintiffs ultimately succeed in proving their claims, this case could set a transformative legal precedent that will reshape the way AI-art is regulated in the United States. As the legal battle unfolds, this case will undoubtedly set a guiding tone for how courts interpret the relationship between AI innovation and intellectual property rights.