Download a PDF version of this article here.

‘The American people have given you something really valuable, the airways, for free,’ he said, talking about the broadcasters, his eyes popping at the word ‘free.’ Slowing down for emphasis, he added: ‘So shouldn’t we get something back for free? Which is great television. That’s the social contract, right?’1

-David Goodfriend (January 31, 2019)

Introduction

David Goodfriend is the founder of the broadcast television retransmission service “Locast.” The industry’s latest creative destructor that has made itself available to a majority of the United States in less than three years.2 Using antennas placed atop high altitudes, Locast seizes and retransmits over-the-air live broadcast signals to “almost any digital device, at any time, in pristine quality” using a digital stream.3 Its mobile app and website operate much like a TV on-demand service; in some areas, users can scroll through approximately 50 live feeds. Locast does so, however, without the consent of any of the content’s owners or broadcasters.4 Nonetheless, Goodfriend challenged the likes of ABC, NBC, CBS, and FOX to sue him in an interview with the New York Times in early 2019.5 Goodfriend’s dare has since been answered. Ten of the largest media companies in the world have filed a joint complaint against Goodfriend in the Southern District of New York.6 They argue that Locast’s unconsented retransmissions infringe their exclusive public performance rights under the Copyright Act of 1976.7 Given relevant precedent, they have every right to be confident. After all, in 2014 a widely publicized company named Aereo offered an identical service lacking the same consent from these same plaintiffs.8 And Aereo failed in dramatic fashion. Five months after a 6-3 Supreme Court concluded that its internet-based retransmissions were “public performances” within the meaning of section 106(4),9 Aereo declared bankruptcy.10 Therefore, the broadcasters argue that§ 111. Limitations on exclusive rights: Secondary transmissions.

(a) Certain Secondary Transmission Exempted. –The secondary transmission of a performance or display of a work embodied in a primary transmission is not an infringement of copyright if – (5) the secondary transmission is not made by a cable system but is made by a governmental body, or other nonprofit organization, without any purpose of direct or indirect commercial advantage, and without charge to the recipients of the secondary transmission other than assessments necessary to defray the actual and reasonable costs maintaining and operating the secondary transmission service.20[The clause] would exempt the activities of secondary transmitters that operate on a completely nonprofit basis. The operations of nonprofit “translators” or “boosters,” which do nothing more than amplify broadcast signals and retransmit them to everyone in an area for free reception, would be exempt if there is no “purpose of direct or indirect commercial advantage,” and if there is no charge to the recipients “other than assessments necessary to defray the actual and reasonable costs of maintaining and operating the secondary transmission service.” This exemption does not apply to a cable television system.42

I. Textual Analysis of § 111(a)(5)

For convenience I reiterate the language of Section 111(a)(5) below:§ 111. Limitations on exclusive rights: Secondary transmissions.

(a) Certain Secondary Transmission Exempted. –The secondary transmission of a performance or display of a work embodied in a primary transmission is not an infringement of copyright if – (5) the secondary transmission is not made by a cable system but is made by a governmental body, or other nonprofit organization, without any purpose of direct or indirect commercial advantage, and without charge to the recipients of the secondary transmission other than assessments necessary to defray the actual and reasonable costs maintaining and operating the secondary transmission service.45II. Pre-History: The Rise of Broadcast and Retransmission Technologies

A. 1887-1927: Development of a National Broadcasting Vision and Policy

Heinrich Hertz’s experiments on the wave structure of electromagnetic radiation in 1887 became the catalyst for electronic communication.58 Engineers and physicists began to understand that information—including the sound of a voice or a picture—could be encoded on sine waves by modulating the wave itself. Innovation was swift. By 1901, the first wireless telegraph signal was successfully transmitted across the Atlantic Ocean.59 However, the creation of a centralized authority responsible for allocating the radio wave spectrum was needed before it could ever be put to mass use. To illustrate, assume that you live in New York City and you want to listen to WOR 710 AM. The station’s corresponding number signifies that it transmits audio signals using an amplitude modulation (i.e. “AM”) of 710,000 herz.60 This means that the DJ’s voice is being modulated to an electronic sine wave by varying the amplitude of the wave itself 710,000 times per second.61 The station takes this modulated wave and distributes it using a transmitter tower.62 As the transmitted modulated wave scours the horizon, your radio is looking to receive it. To instruct your radio set to receive the wave, you turn your tuner knob to the corresponding herz number. Thus, by turning your knob to 710 AM, you instruct your set to only receive sine waves that modulate at 710,000 herz. Once the wave is received, your radio clips off the part of the wave that contains the DJ’s voice and sends it directly to your speakers for your listening pleasure. But what happens if a second radio station transmits using an identical hertz frequency within reach of your set? Unfortunately, receivers are incapable of differentiating between the two.63 Your radio will receive both, resulting in “interference” as the two transmissions battle for reception dominance.64 Making matters worse, there is a limited number of adequate frequencies available for quality modulation.65 Thus, by the 1920s, Congress realized that the spectrum presented a “Tragedy of the Commons”66 scenario:[R]adio policy in the United States was grounded in the conviction that the spectrum belonged to the public. Everyone should have a right to obtain a license and use the spectrum. However . . . policy makers increasingly viewed the radio spectrum as a finite resource. At any one time, only a limited band of frequencies was available for wireless, and interference among stations (often using poorly tuned equipment) limited the number that could transmit at any one time. All citizens might own the ether, but if everyone tried to use it its value would be destroyed. Throughout the early history of radio (at least until 1927), radio policy in the United States had to deal with a potential contradiction. Decision makers wanted everyone to have a right to use the spectrum, but they increasingly came to the conclusion that the government would have to place limits on access to the radio spectrum to avoid overexploitation, or in other words, destructive interference.67

[A] new, wide-open frontier, akin to the American West, where men could pursue individual interests free from repressive authoritarian and hierarchical institutions. [The amateur operators] resented attempts by the navy and private companies to monopolize the spectrum for commercial or military gain.72

B. 1927-1934: Invention of Broadcast Television and Creation of the FCC

On April 7, 1927, Bell Telephone invited Secretary Hoover to its Washington D.C. laboratory.86 Hoover was instructed to sit in front of—what we would now call—a broadcast camera and give a pre-written speech.87 His image and voice were captured and transmitted across 200 miles to an audience of newspaper reporters and dignitaries gathered in a New York City-based auditorium.88 Those in attendance witnessed the first long-distance use of television broadcasting in history.89 And they would hear Hoover utter the following words: “Today we have, in a sense, the transmission of sight for the first time in the world’s history. Human genius has now destroyed the impediment of distance in a new respect, and in a manner hitherto unknown.”90 Within twenty years, the following occurred: The government issued the first commercial television station license,91 President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivered the first live broadcast of a Presidential speech in American history,92 and many of the named plaintiffs in theAlthough the cable, telegraph, telephone, and radio are inextricably intertwined in communication, the Federal regulation of these agencies, in our country, is not centered in one governmental body. The responsibility for regulation is scattered. This scattering of the regulatory power of the Government has not been in the interest of the most economical or efficient service.95

For the purpose of regulating interstate and foreign commerce in communication by wire and radio so as to make available, so far as possible, to all the people of the United States . . . a rapid, efficient, Nation-wide, and world-wide wire and radio communication service with adequate facilities at reasonable charges . . . .97

C. 1934-1955: Invention of Retransmission Technologies and CATV

In 1948, Leroy “Ed” Parsons lived in Astoria, Oregon.109 Astoria was the quintessential rural community shunned by the broadcasting world: It had a population of 10,000 and the nearest television station was located in Seattle—at least 150 miles away.110 Because of this distance, the mountainous terrain between Astoria and Seattle, and the freeze order, no viewable broadcast signal could reach Astoria and its citizens.111 Nonetheless, Parsons found a way. An engineer by trade, Parsons placed an antenna on top of the roof of a local hotel where the distant Seattle-based transmissions were weak but nevertheless receivable.112 He then installed an amplifier that “boosted” the signal and strung a cable from the device to the adjacent building where he lived.113 As the boosted signal travelled through the cable and into his television set, the broadcast was rendered watchable. In doing so, Ed Parsons unknowingly invented cable television.114 When the surrounding citizenry received word of what Parsons accomplished, chaos ensued. Hundreds of strangers visited his home to glimpse the electronic medium they had heard so much about.115 As Parsons retells it:The first problem was too many people coming into our apartment or penthouse. We literally lost our home. People would drive for hundreds of miles to see television. We had gotten considerable publicity . . . when people drove down from Portland or came from The Dalles or from Klamath Falls to see television, you couldn’t tell them no. So I approached the hotel manager and suggested that it would be a simple matter to drop a cable down the elevator shaft and put a set in the lobby of the hotel. He thought that was a wonderful idea. So we did. A short time later, he asked me to remove the set because the lobby was so full people couldn’t get in to register.116

In essence, this threat derives from CATV’s ability to import multiple television signals from many distant stations into cities where local and area television stations are already reaching the viewing public. Because the same television programs are broadcast in many different markets, the importation by CATV into such well-served cities of the signals from stations in other markets means that the exclusivity of the local station as to many—if not most—of its programs will be destroyed. To the extent that a program is viewed on an imported channel, the benefit of exclusivity, for which the local station has bargained, is destroyed—to the damage of the local station, the copyright owner and, ultimately, the public. For, when CATV subscribers watch network programs, feature films, or syndicated film programs imported from distant stations, the local viewing audience is fractionated and the local station is deprived of advertiser support, since it can no longer offer to advertisers as large an audience of local viewers. The resulting decrease in advertising revenue means at least that programing must be curtailed and at worst that the local station will be forced off the air.139

III. Legislative History of Copyright Act § 111(a )(5)

A. Addressing the Complexity of the Act’s Legislative History

The legal community has long used legislative history to interpret statutory language.142 However, this approach to interpretation proves uniquely difficult to apply for the Copyright Act of 1976. After all, the Act’s legislative record spans more than 30 studies, three Register reports, four committee prints, six series of subcommittee hearings, 18 committee reports, and the introduction of at least 19 general revision bills (the history of section 111 alone spans 22 congressional sessions143). 144 Yet, “one can read this history in its entirety and find no evidence that any member of Congress intended anything in particular to follow from many provisions of the statute.” 145 Compounding this difficulty, “[m]ost of the [Copyright Act] was not drafted by members of Congress . . . [i]nstead, the language evolved through a process of negotiation among authors, publishers, and other parties with economic interests in the property rights the statute defines.”146 Therefore, Professor Jessica Litman of Michigan Law characterizes the Act’s development as “reflect[ing] an anomalous legislative process designed to force special interest groups to negotiate with one another.”147 And as will be discussed below, section 111(a)(5)’s development was more than consistent with Litman’s characterization; involved were some of the largest media entities in the world, including: NBC, ABC, CBS, Disney, Universal Pictures, Twentieth Century Fox, the NFL, MLB, the Motion Picture Association, and the Screen Actors Guild.148 Nevertheless, these complexities should not be treated as an excuse to disregard the informational richness that this history provides for the present inquiry. As Professor Litman further states:[I]t would be a mistake to conclude that simply because the statutory language and legislative history are difficult to interpret, they convey nothing about what the 1976 Act intended to accomplish. The statute was a complicated and delicate compromise, but the nature of most aspects to that compromise is possible to unearth.149

B. 1955-1965: Birth of the Nonprofit Booster/Translator Exception

By 1955, Congress had been quarreling over whether public performance copyright liability should extend to radio and television broadcast retransmissions for nearly 30 years. 152 After decades of dead bills and failed initiatives, Congress sought the help of the Copyright Office. Funds were appropriated for the creation of a special committee of copyright experts, entitled the Subcommittee on the Judiciary Subcommittee on Patents, Trademarks, and Copyrights.153 Arthur Fisher, then-Register of Copyrights for the Library of Congress, assumed its lead.154 However, Fisher feared that the subcommittee—occupied by multiple representatives of the various special interest groups– would endlessly quarrel and thus, stall the amendment efforts.155 He responded to these fears by insisting that the Copyright Office be solely responsible for putting forward any future statutory recommendations; rendering the members of the newly created subcommittee as mere advisors.156 Therefore, the ultimate proposal put forward by Fisher’s Office in 1961 lacked sufficient industry compromise.157 This proved to be catastrophic, and allowed the special interests to capitalize and force their influence on the Office’s revisionary efforts. Therefore (and rather, ironically), Fisher’s avoidance of the special interests incidentally provided them with a larger platform for section 111(a)(5)’s eventual development. Fisher’s 1961 report proposed: “The statute should exempt the mere reception of broadcasts from public performance right, except where the receiver makes a charge to the public for reception.”158 Interpreted broadly, it would cast liability on all unauthorized forms of broadcast retransmissions containing copyrighted material. In other words, all retransmission technologies (including boosters, translators, and CATV) would be infringing regardless of their profit motive. Interpreted narrowly (i.e., that broadcast reception is the only form of broadcast interaction that copyright law is concerned with), the proposal would immunize every form of retransmission. Multiple public comments were filed in opposition.159 Herman Finkelstein, on behalf of the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (“ASCAP”) and Chairman of the ABA’s Committee on Program for Copyright Revision, went so far as to call the draft “evil.”160 A number of ABA members echoed Finkelstein’s sentiments, and “insisted that they would prefer the current outmoded statute.”161 This vitriol forced the Copyright Office to start from scratch and prolong the revision process. The next tentative draft wouldn’t be circulated until 1963.162 By this time, Fisher would pass away163 and at least 650,000 Americans would be hooked to cable.164 Replacing Fisher as Register of Copyrights was Abraham L. Kaminstein.165 Contrary to Fisher’s approach, Kaminstein insisted that the Copyright Office seek industry input. After analyzing the comments regarding the previous 1961 revision, the Copyright Office proposed—for the first time—that boosters and translators should be exempt from public performance liability.166 However, they refused to extend immunity to CATV operations.167 Barbara A. Ringer, Chief of the Copyright Office’s Examining Division, introduced the language to many of the same parties who opposed the previous draft (and the current plaintiffs in the[The problem] that we see here is the rather interesting question of rebroadcasting or retransmission. And here, of course, there is a vast amount of technology and a vast amount of ignorance, probably on our part as much as anybody else’s. But essentially, as we see it, there are two situations where money is involved: (1) the community antenna or CATV system, where the broadcast is picked up and retransmitted over wires to a special receiving set, and where the subscriber pays for the service; and (2) the booster system, where the signal is merely magnified and where anybody in the vicinity can pick the broadcast up.

. . . With respect to rebroadcasting or rediffusion, we felt it desirable to exempt relays, boosters, master antennas on apartment house roofs, and the like. But, on the basis of the representations that have been made to us, we did not feel that a commercial community antenna system, which installs special equipment on a subscriber’s receiving set and charges him for operating the set, should be exempted, and it is not exempted under this draft provision. On the basis of our knowledge, which is far from perfect, we felt that there is a distinction between a system of this sort—where, from what we have been told, people are really operating for profit—and the situation where somebody puts an antenna up on a hill and lets everybody have the benefit of their largesse, wherever the money comes from. Now we don’t know all we should about this, and we are anxious to be educated.169I wish to make plain that community antennas, boosters, translators and rooftop antennas should all be treated identically and should all be exempted from the operation of the Copyright Act. . . . The paramount interest is the public’s. The public’s interest is to have the greatest amount of television service at the lowest possible cost.

. . . If and so long as the public is to have free television service, [they] must have the correlative right to select the equipment which is most efficient and most adapted to particular needs. . . .Those who manufacture, sell, lease or install reception equipment, whether it be sets, boosters, translators, community antennas, master antennas or rooftop antennas are all in the same business. They do not sell time. They do not sell programs. They do seek to make a profit by dealing in equipment. Without doubt, there would be no market for reception equipment if there were not broadcasts of copyrighted materials. . . . There is simply no “performance,” if that word still has a meaning, in the passing of an electric current through tubes and wires-which is all a community antenna accomplishes. The irrelevancy of “performance” is shown by the draft’s exemption of boosters, which are as much broadcasting devices as any television station.171C. 1965-1966: Debate & Authorship of the Provision in House Subcomm. No. 3

After a decade of hearings and multiple drafts, Abraham Kaminstein introduced a proposal for a new Copyright Act to Congress on February 4, 1965.184 Its version of the nonprofit retransmission exception was as follows:§109. Limitations on exclusive rights: Exemption of certain performances and exhibitions

Notwithstanding the provisions of section 106, the following are not infringements of copyright: (5) the further transmitting to the public of a transmission embodying a performance or exhibition of a work, if the further transmission is made without altering or adding to the content of the original transmission, without any purpose of direct or indirect commercial advantage, and without charge to the recipients of the further transmission;185[T]here is no exemption in this bill for community antenna television operations. . . . . . The number of the systems, which in early January of this year totaled around 1,600, has been growing very rapidly at the rate of approximately 40 systems per month. They now bring the broadcast of more than 400 television stations to well over a million and a half subscribers. The industry is reported to have garnered income last year in excess of $100 million and the anticipation for the future is even rosier.

. . . In our view, there may be valid arguments on both sides of this entire question. . . . On balance, however, it is our view that the CATV operators are making a performance to the public of a copyright owner’s work. This performance results in a profit which in all fairness the copyright owner should share. Unless he is compensated, the performance can have damaging effects upon the value of the particular copyright. For these reasons, therefore, we have not included an exemption for commercial community antenna systems in the bill.199The entire fabric of our free system of television programming depends on the exclusivity of television program rights. The ability of a television network to persuade an advertiser to include a particular station on the network lineup and the revenues which the network and the station will receive depend upon whether [sic] that station is the exclusive outlet for the network in the particular city, since a network advertiser will usually not pay twice for the same coverage.

. . . Exclusivity, that is, the ability of the program owner to control its exposure to the public, is thus essential to a continuing supply of television programs which, in turn, is essential to the survival of television itself. . . . As an inducement, to the production and broadcast of television programs, there is no realistic substitute for exclusivity. . . . CATV originally did and still does operate in areas of poor television reception . . . [i]n its historic role, CATV has fulfilled an important function as a supplement to our system of free television . . . More recently, [however], an entirely different type of CATV has been emerging. . . . There are no geographical bounds for ‘CATV unlimited.’ Increasingly, multi-hop microwave relays are being sought or planned to import stations from metropolitan centers across many hundreds of miles and several States. These multi-channel systems, importing distant stations both off the air and by microwave, are trying to mushroom into cities and towns of all sizes where reception of local and area broadcasting stations is excellent. . . . In short, ‘CATV unlimited’ is a new type of CATV with capabilities and operations only faintly resembling historic CATV. As CATV’s purpose and operations expand beyond providing an auxiliary service, CATV becomes a threat to the public interest in free, diverse, and competitive, local and area television broadcast services. In essence, this threat derives from CATV’s ability to import multiple television signals from many distant stations into cities where local and area television stations are already reaching the viewing public. Because the same television programs are broadcast in many different markets, the importation by CATV into such well-served “cities of the signals from stations in other markets means that the exclusivity of the local station as to many—if not most—of its programs will be destroyed.206§111. Limitations on exclusive rights: Secondary transmissions.

(a) Certain Secondary Transmission Exempted. – (2) Notwithstanding the provisions of subsection (c), but subject to the provisions of subsection (b), the secondary transmission to the public of a primary transmission embodying a performance or display of a work is not an infringement of copyright if the secondary transmission is made by a governmental body, or other nonprofit organization, without any purpose of direct or indirect commercial advantage, and without any charge to the recipients of the secondary transmission other than assessments necessary to defray the actual and reasonable costs of maintaining and operating the secondary transmission service. (b) Certain Secondary Transmission Fully Actionable. –Notwithstanding the provisions of . . . clause[] (2) . . . of subsection (a), the secondary transmission to the public of a primary transmission embodying a performance or display of. a work is actionable . . . if: (2) the secondary transmitter, within one month before or after the particular secondary transmission, originates any transmission to those members of the public to whom it also makes the secondary transmission, except for no more than two transmission programs at any one time unaccompanied by any commercial or political advertising and consisting solely of: weather, time, and news reports free from editorial comments; agricultural reports; religious services; and local proceedings of governmental bodies; or (3) the secondary transmitter, within one month before or after the particular secondary transmission, makes any separate direct charge for any particular transmission it makes to those members of the public to whom it also makes the secondary transmission; or (4) the primary transmission is not made for reception by the public at large but is controlled and limited to reception by particular members of the public; or (5) the secondary transmission is made for reception wholly or partly outside the limits of the area normally encompassed by the primary transmission . . . (6) the secondary transmission is made for reception wholly or partly within the limits of an area normally encompassed by one or more transmitting facilities, other than the primary transmitter if – (A) a transmitting facility other than the primary transmitter has the exclusive right within that area, under an exclusive licenses or other transfer of copyright, to transmit the same performance or display of the work, and (B) the transmitter having the exclusive right or any other copyright owner has given written notice of such exclusive right to the secondary transmitter at least ten days before the primary transmission, in accordance with requirements that the Register of Copyright shall prescribe by regulation.226D. 1966-1967: Fortnightly, the FCC, Debate of the Whole, and Removal of § 111

At this point, it is essential to discuss what was happening outside of Congress. First, in the Southern District of New York, United Artists Television, Inc. —producer of The Fugitive and Gilligan’s Island231—filed suit against Fortnightly, Inc., a West Virginia CATV operator.232 United Artists argued that CATV retransmissions infringed their public performance right (an unresolved legal question at the time).233 And on May 23, 1966, the Southern District agreed.234 Judge William Herlands held that commercial CATV retransmissions constituted a “public performance for profit.”235 He acknowledged that exempting some categories of retransmission technologies might be desirable “purely on policy grounds.” Nonetheless, those distinctions were an issue to be resolved by Congress.236 Second, the FCC buckled to years of pressure and asserted regulatory power over CATV.237 The FCC’s “First Order” required CATV using microwave relay to seek permission from local stations to retransmit their content, and were prohibited from carrying their programs into markets already served.238 However, because most urban CATV didn’t rely on microwave relay, they found themselves otherwise exempt from the FCC’s scrutiny.239 Therefore, when the Whole House reconvened on April 6, 1967,240 CATV was desperate. Other than those operations based in urban markets, the FCC’s Order shut the door to CATV’s expansion to much of the country already accessible to local station signals. Further, regardless of whether or not the law was adopted, CATV was going to be forced to pay for copyright unless the Act contained an explicit exception. Enter: Rep. Arch A. Moore, House Republican for West Virginia.241 On April 5, 1967, Rep. Moore sought to destroy Section 111 and exempt all CATV from copyright liability. He actively circulated letters and comments to his colleagues urging them to accept an amendment doing the same.242 The author has been unable to find evidence explaining Moore’s motives. But one can speculate: In West Virginia, Moore served the cities of Clarksburg and Fairmont—the exact two cities where Fortnightly was headquartered and Operated.243 Rather than attack its merits, Moore criticized section 111’s development. Specifically, Moore grounded his opposition on a technical issue: He claimed that the House Judiciary, by assuming sole authority over the CATV issue and the new copyright law, interfered with the exclusive jurisdiction of the House’s Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce:“[W]hat we seek to do in this legislation is control CATV by copyright. I say that is wrong. I feel if there is to be supervision of this fast-growing area of news media and communications media, it should legitimately come to this body from the legislative committee that has direct jurisdiction over the same, [the Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee]. . . . I believe the ramifications of controlling CATV through the copyright mechanism is highly technical, is in error, and is a grievous mistake. Should not the recommendations in this matter, I say to this Committee, come from the legislative committee that has the direct responsibility and that which has the primary jurisdiction in this matter?”244

[Rep. Moore] has offered an amendment which could not be more mischievous than anything I could think of. . . . This subject is complicated . . . [i]t has been up before our committee on several occasions. The bill now before the House attempts to modify that decision in order to give CATV some rights they do not already have, and it would partially overcome the decision of the New York court.

. . . I take it that down in the gentleman’s territory there is a lot of CATV. At least one other gentleman on my side who is in the same area has indicated the same thing. [But] [s]omewhere along the line we have to be fair. We have to balance off the originating station with the CATV. I believe this bill does about as good a job in trying to balance those interests as we could find. . . . [I]f the substitute is defeated, an amendment will be offered by the gentleman from New York [Mr. Ottinger], which would strike all of section 111 and put the subject matter back in our committee. Reluctantly, I personally did not want to see all of this happen, but in view of the contentions that have arisen on this floor, rather than accept the amendment now and go ahead and do what the gentleman from North Carolina has in mind at this point, it would be much better to accept the Ottinger amendment . . . . At first I did not think this ought to be done. I had a feeling that we ought to go along with section 111. But the way this thing is developing, the worst type of legislation you could have at this point would be the substitute. It would ruin the whole purpose of the copyright law with reference to the division, in fairness, between the originating station and CATV itself.255E. 1967-1973: Fortnightly and Clay J. Whitehead

After the Second Circuit affirmed the Southern District’s decision in Fortnightly,266 the Supreme Court granted certiorari in 1968.267 As previously discussed, the government saw this as an opportunity to end the CATV debate. The Solicitor General implored SCOTUS to administer a judicial compromise accommodating the relevant interests.268 However, the Supreme Court refused.269 Justice Stewart, writing for a 5-1 majority,270 acknowledged that the 1909 Act needed revision given the modern nature of retransmission technologies.271 But in a shocking turn-of-face, Stewart reversed the lower courts and held that CATV was immune from copyright public performance liability under the existing Act.272 He acknowledged the government’s pleas for help.273 but “decline[d] the invitation. That job is for Congress.”274 By the time this opinion was announced, approximately 2,000 cable systems were in operation around the country—serving 2.8 million homes.275 All of which would be free to compete against the local stations without needing to pay copyright clearance fees thanks to the Stewart majority. By this time, the FCC became convinced to enter the fray.276 Two years before the Supreme Court’s decision in Fortnightly, the agency issued a freeze on the importation of all cable signals into the top 100 markets.277 A protectionist policy aimed at preserving the exclusivity of the major local stations.278 Next, Senator John L. McClellan (D-AK)—Chairman of the Senate Subcommittee of the Patents, Trademarks, and Copyrights—reintroduced the Copyright Revision Bill for consideration by his subcommittee in 1969.279 Although there is little recorded evidence of their negotiations, we do know the result: A compromise. Representatives of commercial CATV agreed to make reasonable payments for the use of copyrighted material under a compulsory licensing scheme.280 In exchange, the FCC would remove their freeze order and allow CATV to grow. The bill went through significant edits to reflect these understandings.281 As enumerated, the Subcommittee’s draft provided that CATV would have to comply with a licensing fee schedule based on a percentage of the CATV’s operator’s gross receipts.282 Existing CATV would be grandfathered in.283 Most importantly, McClellan’s draft re-adopted the nonprofit retransmission exception in its entirety.284 By December 10, 1969, the Senate Subcommittee on Patents, Trademarks, and Copyrights recommended the below text to the Judiciary Committee:285§ 111. Limitations on exclusive rights: Secondary transmissions.

(a) Certain Secondary Transmission Exempted. – (4) the secondary transmission is made by a governmental body, or other nonprofit organization, without any purpose of direct or indirect commercial advantage, and without any charge to the recipients of the secondary transmission other than assessments necessary to defray the actual and reasonable costs of maintaining and operating the secondary transmission service.286 (b) Secondary Transmission of Primary Transmission to Controlled Group. – Notwithstanding the provisions of subsection (a) and (c), the secondary transmission to the public of a primary transmission embodying a performance or display of a work is actionable as an act of infringement under sections 501, and is fully subject to the remedies provided by sections 502 through 506, if the primary transmission is not made for reception by the public at large but is controlled and limited to reception by particular members of the public.287 (c) Secondary Transmission by Cable Systems. – (2) Subject to the provisions of subsections (a) and (b), but notwithstanding the provisions of clauses (2) and (4) of this subsection, the secondary transmission to the public by a cable system of a primary transmission made by a broadcast station licensed by the Federal Communications Commission and embodying a performance or display of a work is subject to compulsory licensing under the conditions specified by subsection (d) in the following cases.288 (B) Where the reference point of the cable system is within the local service area of the primary transmitter;(1) The FCC’s absolute freeze on distant signal carriage into well-served markets would be abolished.308 Signal importation was allowed under certain limitations depending on the size of the imported market.309 However, duplicative signal importation was prohibited.310 Upon acceptance, these regulatory changes would be put into effect promptly.311

(2) All parties pledged to support separate copyright legislation.312 This would provide for a compulsory license scheme for CATV retransmissions.313 The fee obligation would cover all local signals and a certain number of distant signals.314 The existing nonprofit exception would remain in the bill.315F. 1973-1976: Scrutiny of Nonprofit Cable and Adoption of the Copyright Act

Despite pledging themselves to support speedy passage of the copyright legislation,320 the major copyright owners voiced multiple gripes with section 111’s existing language on August 1, 1973.321 Most notably, Jack Valenti, President of the Motion Picture Association of America, Inc. (also speaking on behalf of the Association of Motion Picture and Television Producers Inc.), argued that the nonprofit retransmission exception was “overly-broad.”322 He emphasized that this grant of immunity should only cover passive retransmission devices—nonprofit translators, boosters, and “similar secondary transmitters.”323 Specifically, Valenti testified:There are a large number of nonprofit organizations in the United States. Many of them operate big enterprises. Moreover, there are already in existence at least 15 municipally-owned CATV systems and there is an increasing drive across the country for municipal ownership of cable systems. . . . The copyright owners are concerned that increasing governmental or non-profit ownership of cable systems may deprive them of license fees for the use of their product.

A free ride for these entities cannot be squared with the achievement of the public purpose which underlies the copyright system. . . . A legal requirement that copyrighted film programs be available to nonprofit and governmental users for free is no less repugnant to the purpose of the copyright system because the user does not intend to make a profit. No matter how well governmentally and nonprofit enterprises function, no one would suggest that the law require that their suppliers of equipment, products, and services furnish them free of charge.324By the same token, Section 111(a)(4) exempts non-profit and government owned CATV systems from the requirement to pay fees. Here again, it would seem more prudent public policy, in light of our national policy encouraging private enterprise, to leave these two reception and distribution facilities on an even competitive basis by striking Section 111(a)(4).330

NCTA also suggests that . . . Section 111(a)(4) should be eliminated . . . . We agree that the exemption for governmental and nonprofit systems is overly broad, but we do not agree that the provision should be deleted.

In our initial statement filed with the Committee on August 1, 1973, we pointed out that this provision is concerned with the operation of nonprofit “translators” or “boosters” which do nothing more than amplify broadcast signals and retransmit them to everyone in an area for free reception. These translators and boosters have always been subject to FCC regulation and require retransmission consent of the originating station under Section 325(a) of the Communications Act. However, the language of the exemption contained in Section 111 (a)(4) would be equally applicable to cable systems which are operated by governmental bodies or nonprofit organizations. Thus, in order to limit the exemption to nonprofit translators and boosters and similar secondary transmitters, we proposed to insert into the text of Section 111(a)(4) the words “… is not made by a cable system …”. Since we continue to believe that the exemption should be maintained for the benefit of the translator and booster systems described, we submit that complete elimination of this exemption would be improper and that the appropriate solution is adoption of the amendment we have submitted . . . .331§ 111. Limitations on exclusive rights: Secondary transmissions.

(a) Certain Secondary Transmission Exempted. – (4) the secondary transmission is not made by a cable system but is made by a governmental body, or other nonprofit organization, without any purpose of direct or indirect commercial advantage, and without any charge to the recipients of the secondary transmission other than assessments necessary to defray the actual and reasonable costs of maintaining and operating the secondary transmission service.332Clause (4) would exempt the activities of secondary transmitters that operate on a completely nonprofit basis. The operations of non-profit ‘translators’ or ‘boosters,’ which do nothing more than amplify broadcast signals and retransmit them to everyone in an area for free reception, would be exempt if there is no charge to the recipients ‘other than assessment necessary to defray the actual and reasonable costs of maintaining and operating the secondary transmission service.’ This exemption does not apply to a [CATV].334

IV. Analysis

Goodfriend’s claim that “[e]very American has the right to access broadcast for free”335 is hyperbolic. Although access has long been a national priority,336 Congress has consistently balanced this pursuit against the business needs of copyright owners, networks, and local stations.337 No better example of this is found than in the legislative history of section 111(a)(5). At the time, CATV provided the best opportunity for achieving limitless television access. Nevertheless, Congress refused to grant it immunity—regardless of whether it operated as a nonprofit. Why? Because the section’s authors felt it was unfair that CATV continued to split viewership by impeding upon the market exclusivity of local stations without paying for copyright fees.338 In other words, CATV’s lack of “passivity” made it unworthy of immunization under section 111(a)(5).339 And this understanding is encapsulated in the House Report discussing its language:[The clause] would exempt the activities of secondary transmitters that operate on a completely nonprofit basis. The operations of nonprofit “translators” or “boosters,” which do nothing more than amplify broadcast signals and retransmit them to everyone in an area for free reception, would be exempt if there is no “purpose of direct or indirect commercial advantage,” and if there is no charge to the recipients “other than assessments necessary to defray the actual and reasonable costs of maintaining and operating the secondary transmission service.” This exemption does not apply to a cable television system.340

Congress balanced competing concerns. It recognized the public

interest in expanding access to free broadcast television. At the same time, it

believed that for-profit retransmission services should, in

fairness, share their profits with the programs’ creators. Non-profit retransmission

services, by contrast, generate no such profits to share, so Congress exempted

them from copyright liability altogether. The distinction the statute draws

thus is not between Internet-based systems and over-the-air boosters and

translators. It is between for-profit and non-profit systems.

Conclusion

After analyzing whether the nature of* Editor-in-Chief, Tenth Volume of the New York University Journal of Intellectual Property & Entertainment Law and J.D. Candidate, Class of 2021, New York University School of Law. The author offers gratitude to Professor Jeanne Fromer for her guidance, mentorship, and editing throughout this process, along with Professor Amy Adler, Professor Barton Beebe, and Professor Scott Hemphill for their early encouragement. The piece is dedicated to the Tenth Volume.

- Edmund Lee, Locast, a Free App Streaming Network TV, Would Love to Get Sued, N.Y. Times, Feb. 3, 2019, at BU1 (emphasis added).

- Locast, https://www.locast.org/ (last visited Apr. 26, 2021) (advertising that Locast retransmission signals were available to 51.7% of the U.S. population as of the date visited).

- Lee, supra note 1; Live TV Guide, Locast, https://www.locast.org/cities/501 (last visited Feb. 21, 2021) (in the New York market alone, approximately 50 live fees are available, including: CBS, NBC, FOX, ABC, and PBS).

- Lee, supra note 1.

- See id. (“Mr. Goodfriend said he would welcome a legal challenge from the networks.”).

- Amended Complaint, ABC, Inc. v. Goodfriend, No. 19-cv-7136 (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 30, 2020) (named plaintiffs include: ABC, Disney, Twentieth Century Fox Film, CBS Broadcasting, CBS Studios, FOX Television Stations, FOX Broadcasting Company, NBCUniversal Media, Universal Television, and Open 4 Business Productions).

- Id.at 7; see also 17 U.S.C. § 106(5) (2012).

- Aereo, like Locast, used antenna technology capable of seizing over-the-air broadcasting signals and translating these signals into “streamable” data for digital devices. ABC, Inc. v. Aereo, Inc., 573 U.S. 431, 436 (2014). However, unlike Locast, Aereo’s system was made up of “thousands of dime-sized antennas housed in a central warehouse.”Id.ABC, CBS, NBC, FOX, and other major broadcast companies filed suit in response. Warren Richey, Aereo Internet Service v. TV Broadcasters: US Supreme Court to Decide, The Christian Science Monitor, Apr. 20, 2014, https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Justice/2014/0420/Aereo-Internet-service-vs.-TV-broadcasters-US-Supreme-Court-to-decide .

- See Aereo, Inc., 573 U.S. at 451.

- Emily Steel, Aereo Concedes Defeat and Files for Bankruptcy, N.Y. Times, Nov. 22, 2014, at B2, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/22/business/aereo-files-for-bankruptcy.html .

- Janko Roettgers, Major Broadcasters Sue TV Streaming Nonprofit Locast, Variety, July 31, 2019, https://variety.com/2019/digital/news/major-broadcasters-sue-tv-streaming-nonprofit-locast-1203286487/ .

- Locast, supra note 2.

- See id.

- See Answer to Amended Complaint at 2, ABC, Inc. (No. 19-cv-07136); see also 17 U.S.C. § 111(a)(5) (2012).

- See 17 U.S.C. § 111 (enumerating the retransmission compulsory licensing fee scheme).

- Aereo, Inc. , 573 U.S. at 462 (Scalia, J., dissenting) (citing to the network-petitioners’ brief).

- Ben Munson, Donating to Locast is the ‘Single Smartest Move’ Any MVPD/vMVPD Can Make – Analyst, Fierce Video, July 9, 2019, https://www.fiercevideo.com/video/donating-to-locast-single-smartest-move-any-mvpd-vmvpd-can-make-analyst.

- Ben Munson, Sling TV Guide Now Integrates Locast on the AirTV Mini, Fierce Video, Feb. 10, 2021, https://www.fiercevideo.com/video/sling-tv-guide-now-integrates-locast-airtv-mini.

- To the extent that Section 111(a)(5) has been cited, the author has found it briefly mentioned in a single footnote of a published article. Lydia Pallas Loren, The Evolving Role of “For Profit” Use in Copyright Law: Lessons from the 1909 Act, 26 Santa Clara Comput. & High Tech. L.J.255, 279 n.138 (2010).

- 17 U.S.C. § 111(a)(5) (2012).

- See Aereo, Inc. , 573 U.S. at 442 (discussing Section 111 and Congress’s aims for addressing the rise of cable television and its relationship to copyright law).

- See discussion infra Section II.C .

- See Thorin Klosowski, Set Up Your Rabbit Ears for Maximum Reception, Life Hacker (Jan. 16, 2012, 9:00AM), https://lifehacker.com/set-up-your-rabbit-ears-for-maximum-reception-5876388 ( discussing how standard, television antenna works (a.k.a. “rabbit ears”)).

- Copyright Law Revision: Hearings on H.R. 4347, H.R. 5680, H.R. 6831, and H.R. 6835 Before Subcomm. No. 3 of the H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 89th Cong. 1225 (1965), reprinted in Melville B. Nimmer & David Nimmer, Nimmer on Copyright Law: Copyright Law Revision (rev. ed. 2020) [hereinafter 1965 House Hearings] (statement of Ernest W. Jennes. Counsel, Maximum Service Telecaster, Inc.) (“ CATV originally did and still does operate in areas of poor television reception where it provides only the signals of local and area television broadcast stations which CATV subscribers within the service areas of these stations would not otherwise be able to receive adequately because of terrain or other factors. Such CATV systems, for example, place a receiving antenna on a mountain and bring the nearby local and area television signals down the mountainside by cable to communities shielded from direct signals.”). These modest beginnings are exemplified by Leroy “Ed” Parsons and his early work on the technology. See discussion infra Section II.C .

- See id. (“ Early systems had one to three channels. Even in 1964, 70 percent of the CATV systems carried five or fewer channels.”).

- Id.

- See id. (“But new systems already carry up to 12 stations, and systems with 20, 30 or 40 channels are planned.”).

- See id. (“ There are no geographical bounds for ‘CATV unlimited.’ Increasingly, multi-hop microwave relays are being sought or planned to import stations from metropolitan centers across many hundreds of miles and several States.”).

- See id.at 1226 (“ As CATV’s purpose and operations expand beyond providing an auxiliary service, CATV becomes a threat to the public interest in free, diverse, and competitive, local and area television broadcast services. In essence, this threat derives from CATV’s ability to import multiple television signals from many distant stations into cities where local and area television stations are already reaching the viewing public. Because the same television programs are broadcast in many different markets, the importation by CATV into such well-served “cities of the signals from stations in other markets means that the exclusivity of the local station as to many—if not most—of its programs will be destroyed. To the extent that a program is viewed on an imported channel, the benefit of exclusivity, for which the local station has bargained, is destroyed—to the damage of the local station, the copyright owner and, ultimately, the public. For, when CATV subscribers watch network programs, feature films, or syndicated film programs imported from distant stations, the local viewing audience is fractionated and the local station is deprived of advertiser support, since it can no longer offer to advertisers as large an audience of local viewers. The resulting decrease in advertising revenue means at least that programing must be curtailed and at worst that the local station will be forced off the air. With either result, those persons unable or unwilling to pay to hook onto the CATV transmission cable or living in rural or other thinly populated areas which CATV cannot afford to serve will receive off the air a degraded service or none at all.”).

- 1950s TV Shows: What Did People Watch? , Retrowaste , https://www.retrowaste.com/1950s/tv-shows-in-the-1950s/ (last visited Mar. 23, 2021).

- Id.

- Id.

- Many of which, ironically, included the plaintiffs suing Locast. See discussion infra Section III .

- See, e.g. ,House Comm. on the Judiciary, 88th Cong., 1st Sess., Copyright Law Revision Part 3: Preliminary Draft for Revised U.S. Copyright Law and Discussion and Comments on the Draft 424 (Comm. Print 1964), reprinted in 15 Melville B. Nimmer & David Nimmer, Nimmer on Copyright Law: Copyright Law Revision (rev. ed. 2020) [hereinafter CLR Part 3] (comment of George Schiffer) (“I wish to make plain that community antennas, boosters, translators and rooftop antennas should all be treated identically and should all be exempted from the operation of the Copyright Act. . . . The paramount interest is the public’s. The public’s interest is to have the greatest amount of television service at the lowest possible cost.”).

- This included the Copyright Office, which—in their 1963 preliminary draft of the Copyright Act—first assumed the stance that boosters and CATV deserved different treatment under the Act. See Id.at 239 (“The second of the four problems that we see here is the rather interesting question of rebroadcasting or retransmission. And here, of course, there is a vast amount of technology and a vast amount of ignorance, probably on our part as much as anybody else’s. But essentially, as we see it, there are two situations where money is involved: (1) the community antenna or CATV system, where the broadcast is picked up and retransmitted over wires to a special receiving set, and where the subscriber pays for the service; and (2) the booster system, where the signal is merely magnified and where anybody in the vicinity can pick the broadcast up. That’s the second problem: rebroadcasting or rediffusion. . . . With respect to rebroadcasting . . . we felt it desirable to exempt relay boosters . . . [but] we did not feel that a commercial [CATV] . . . should be exempted . . . .”).

- A representative of the National Association of Broadcasters (“NAB”) proclaimed it “illogical” to distinguish between CATV and other retransmission services. Id. at 254.

- See 17 U.S.C. § 111 (2012) (subjecting cable system retransmissions to copyright liability, while immunizing nonprofit retransmission services).

- See id.

- See 17 U.S.C. § 111(a)(5).

- This concern is confirmed by many statements made by the various stakeholders who testified on the matter through the section’s development. 1965 House Hearings, supra note 24, At 1226 (statement of Ernest W. Jennes, General Counsel, Maximum Service Telecaster, Inc.) (“Because the same television programs are broadcast in many different markets, the importation by CATV into such well-served cities of the signals from stations in other markets means that the exclusivity of the local stations to many—if not most—of its programs, will be destroyed. To the extent that a program is viewed on imported channel, the benefit of exclusivity, for which the local station has bargained, is destroyed—to the damage of the local station, the copyright owner and, ultimately, the public.”); Copyright Law Revision: Hearing on S. 1006Before the Subcomm. on Patents, Trademarks, and Copyrights of the S. Comm. on the Judiciary, 89th Cong. 171 (1966), reprinted in Melville B. Nimmer & David Nimmer, Nimmer on Copyright Law: Copyright Law Revision (rev. ed. 2020) [hereinafter 1966 Senate Hearings] (statement of Arthur B. Krim, President, United Artists Group) (“The usual [network] license contract in syndication does not grant the right to authorize the telecast of our programs over additional stations and prevent the licensee station or sponsor from authorizing a community antenna to perform the program. These restrictions are in keeping with the underlying principle of geographical limitation that is central to all television release. . . . [I]t can readily be seen [then] that when a CATV system brings programs from a distant city, it plays havoc with every existing licensing system and either seriously downgrades or utterly destroys the property of the copyright owner.”). It should also be noted that members of the Motion Picture Association, Inc. (“MPA”) additionally expressed reservations about their work being shown in geographies not originally approved. 1965 House Hearings, supra note 24, at 1008(statement of Adolph Schimel, Chairman of Law Committee, Motion Picture Association of America, Inc.) (“Our TV performance license fees depend on the coverage of potential viewers, the timing of the broadcast, the priority and exclusivity of performing rights which we can grant for the area, and other factors in the licensee’s area. . . . We feel strongly that our copyrights should not be freely transmitted, and thereby publicly performed, without our prior license, in this CATV manner. Our license for the original TV broadcast in other cities which the CATV operator captures and re-transmits from the air, does not expressly or impliedly license any further transmission by the CATV operator.”).

- Copyright Law Revision: Hearings on S. 1361 Before the Subcomm. on Patents, Trademarks, and Copyrights of the S. Comm. on the Judiciary, 93d Cong. 303 (1973),reprinted in Melville B. Nimmer & David Nimmer, Nimmer on Copyright Law: Copyright Law Revision (rev. ed. 2020) [hereinafter 1973 Senate Hearings] (statement of Jack Valenti, President, Motion Picture Association of America, Inc.) (emphasis added). See also 1965 House Hearings at 1226 (statement of Ernest W. Jennes, General Counsel, Maximum Service Telecaster, Inc.) (“Besides the destruction of program exclusivity, [CATV] is unfair and inequitable. These multiple-channel CATV systems carry vast quantities of program material. If these systems went out into the marketplace to purchase rights to program material, the cost to the CATV’s—and the corresponding return to the copyright owners—would be substantial.”); see also James J. Popham, The 1971 Consensus Agreement: The Perils of Unkept Promises, 24 Cath. U. L. Rev. 813 (1975) (“[B]ecause the cable television industry’s promise to support specific copyright legislation has not been fulfilled, cable television systems still pay nothing for the broadcast programming for which broadcast stations and networks pay millions of dollars each year.”).

Section 111 would exempt completely from any copyright law provisions secondary transmissions when made at cost by either governmental bodies or nonprofit organizations. . . . [T]his provision was concerned with the operations of “nonprofit ‘translators’ or ‘boosters’ which do nothing more than amplify broadcast signals and retransmit them to everyone in an area for free reception… .” These translators and boosters have always been subject to FCC regulation and require retransmission consent of the originating station under § 325(a) of the Federal Communications Act.

However, the language of the exemption as formulated in § 111 would be equally applicable to cable systems which are operated by governmental bodies or nonprofit organizations. . . . There are a large number of nonprofit organizations in the United States. Many of them operate big enterprises. Moreover, there are already in existence at least 15 municipally-owned CATV systems and there is an increasing drive across the country for municipal ownership of cable systems. . . . The copyright owners are concerned that increasing governmental or non-profit ownership of cable systems may deprive them of license fees for the use of their product. A free ride for these entities cannot be squared with the achievement of the public purpose which underlies the copyright system. That purpose is to promote the useful arts by granting compensation adequate to foster creativity. A legal requirement that copyrighted film programs be available to nonprofit and governmental users for free is no less repugnant to the purpose of the copyright system because the user does not intend to make a profit. - H.R. Rep. No. 94-1476, at 92 (emphasis added).

- Amended Complaint, supra note 6, at ¶ 12.i-iii (“ Locast departs from the activities of a mere booster of broadcast signals in a variety of ways. Among other things, Locast . . . strips from the over-the-air broadcast signals the Nielsen watermarks that measure viewing for local and national advertisers, thereby endangering broadcasters’ advertising revenue.”).

- Jessica D. Litman, Copyright Compromise and Legislative History, 72 Cornell L. Rev. 857, 865 (1987).

- 17 U.S.C. § 111(a)(5) (2012).

- Answer to Amended Complaint, supra note 14 , at 2.

- The Copyright Act defines “secondary transmission” as follows:

17 U.S.C. § 111(f)(2) (2012). Because Locast further transmits primary transmissions simultaneously with their original transmission (via their originating station), it meets the first clause. The second clause is inapplicable because Locast is not a cable system (addressed below).

[T]he further transmitting of a primary transmission simultaneously with the primary transmission, or nonsimultaneously with the primary transmission if by a cable system not located in whole or in part within the boundary of the forty-eight contiguous States, Hawaii, or Puerto Rico: Provided, however, That a nonsimultaneous further transmission by a cable system located in Hawaii of a primary transmission shall be deemed to be a secondary transmission if the carriage of the television broadcast signal comprising such further transmission is permissible under the rules, regulations, or authorizations of the Federal Communications Commission.

- The Copyright Act defines “cable system” as follows:

17 U.S.C. § 111(f)(3) (2012). Because Locast is neither a subscription-based service nor a serve that requires payment, it does not meet this definition. See also Dimitry Dymarsky, FilmOn and the Copyright Act Section 111 Compulsory Licensing, A.B.A., https://www.americanbar.org/groups/litigation/committees/intellectual-property/practice/2015/filmon-copyright-act-section-111-compulsory-licensing/ (last visited Feb. 22, 2021) (discussing the recent case of Fox Television Stations, Inc. v. FilmOn X LLC and the federal court’s conclusion that internet streaming technologies are not “cable television systems” within the meaning of Section 111. See Fox Television Stations, Inc. v. FilmON X LLC, No. 13-758-RMC (D.D.C. Nov. 12, 2015) (opinion under seal)).

[A] facility, located in any State, territory, trust territory, or possession of the United States, that in whole or in part receives signals transmitted or programs broadcast by one or more television broadcast stations licensed by the Federal Communications Commission, and makes secondary transmissions of such signals or programs by wires, cables, microwave, or other communications channels to subscribing members of the public who pay for such service. For purposes of determining the royalty fee under subsection (d)(1), two or more cable systems in contiguous communities under common ownership or control or operating from one headend shall be considered as one system.

- Answer to Amended Complaint, supra note 14, at ¶ 137 (“As a threshold matter, the broadcasters do not challenge [Locast’s] status as a non-profit . . . .”); Amended Complaint, supra note 6 (failing to challenge Locast’s status as a registered nonprofit; rather, challenging its specific operations as not being consistent with a nonprofit).

- See Answer to Amended Complaint, supra note 14.

- Notably, David Goodfriend remains a consultant for DISH. See id. at ¶ 9.

- Id.at ¶ 8; see also Amended Complaint, supra note 6, at ¶ 8.

- See, e.g., John F. Manning, Textualism and the Equity of the Statute, 101 Colum. L. Rev. 1, 4 n.5 (2001) (discussing the philosophy of textualism and the Court’s then-leading proponents of the philosophy, Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas).

- United States v. Ron Pair Enters., 449 U.S. 235, 241 (1989) (quoting Caminetti v. United States, 242 U.S. 470, 485 (1917)).

- Manning, supra note 53 at 4.

- An excellent analysis of both may be found in Jonathan T. Molot’s “The Rise and Fall of Textualism.” 106 Colum. L. Rev. 1 (2006).

- See id.

- Hugh R. Slotten, Radio and Television Regulation – Broadcast Technology in the United States: 1920-1960 3 (2000).

- Id.(discussing Italian inventor Marchese Guglielmo Marconi’s cross-Atlantic wireless telegraph transmission in 1901).

- See How Radio Works, Ga. St. Univ. Libr., https://exhibits.library.gsu.edu/current/exhibits/show/georgiaradio/radio1920s/howradioworks (last visited Feb. 24, 2021).

- See id.

- See id.

- See AM, FM and Sound, Cyber Coll. Internet Campus (May 28, 2013), https://www.cybercollege.com/frtv/frtv017.htm (“First, you can’t put stations on the same frequency that are too close together in a geographic area. They will interfere with each other. And for the same reason you can’t have two stations close together in frequency . . . in the same area.”).

- See Interference with Radio, TV, and Cordless Telephone Signals, Federal Communications Commission, https://www.fcc.gov/consumers/guides/interference-radio-tv-and-telephone-signals (last visited Feb. 24, 2021) (“Interference occurs when unwanted radio frequency signals disrupt the use of your television, radio or cordless telephone. Interference may prevent reception altogether, may cause only a temporary loss of a signal, or may affect the quality of the sound or picture produced by your equipment. The two most common causes of interference are transmitters and electrical equipment.”).

- For AM radio, this range is limited to 540 kHz to 1,600 kHz. The Electromagnetic Spectrum, Lumen, http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/ems2.html (last visited Feb. 24, 2021). For television, however, because “the waves must carry a great deal of visual as well as audio information, each channel requires a larger range of frequencies than simple radio transmission. TV channels utilize frequencies in the range of 45 to 88 MHz and 174 to MHz.”Id.In all, the FCC has only allocated frequency bands between 9 kHz and 275 GHz. Interference with Radio, TV, and Cordless Telephone Signals, FCC , https://www.fcc.gov/consumers/guides/interference-radio-tv-and-telephone-signals(last visited Feb. 24, 2021).

- “[T]ragedy of the commons is an analogy that shows how individuals driven by self-interest can end up destroying the resource upon which they all depend.”. Daniel J. Rankin et al., The Tragedy of the Commons in Evolutionary Biology, 22 Trends in Ecology & Evolution 643 (2007).

- Slotten , supra note 58 , at 6 (emphasis added).

- See id.

- See id. at 6–7.

- Id.at 7.

- A common escapade for young amateur radio operators was to send out fake distress calls to the United States Navy. See id. at 7. This prank was so abundant that military personnel lobbied Congress to transfer control over the spectrum from lay users to the military. See Susan J. Douglas, Inventing Broadcasting 1899-1922, 207–210 (1987) (discussing the navy’s qualms with early, amateur radio operators and their lobbying efforts to take away the spectrum from such operators).

- Slotten, supra note 58 , at 7.

- Titanic Sinks, History, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/titanic-sinks (last updated Apr. 13, 2020).

- See Slotten, supra note 58 , at 7; Erin Blakemore, Why Titanic’s First Call for Help Wasn’t an SOS Signal, Nat’l Geographic (May 28, 2020), https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/why-titanic-first-call-help-not-sos-signal.

- See Radio Act of 1912, 44 Stat. 1162 (1912), amended by Radio Act of 1927, 44 Stat. 1162 (1927).

- See Slotten, supra note 58 , at 8.

- Id. at15.

- See David Moss et. al., Regulating Radio in the Age of Broadcasting, Harv. Bus. Sch. Case 716-043 (2017) (“By 1927, more than 700 stations were battling over 96 available frequencies. This crowding of the broadcast spectrum substantially diminished the quality of radio listening. In fact, the airwaves were so full of interference that many citizens complained that it was often impossible to tune into any station clearly.”).

- Hoover v. Intercity Radio Co ., 286 F. 1003 (1923), appeal dismissed per stipulation, 266 U.S. 636 (1924) (holding that the Secretary of Commerce had no discretion over the issuance of radio licenses); United States v. Zenith Radio Corp. , 12 F.2d 614 (N.D. Ill. 1926) (denying the Secretary of Commerce’s power to file claims against illegal operators).

- See Radio Act of 1927, 44 Stat. 1162 (1927).

- See Slotten, supra note 58 , at 43; see also Radio Act of 1927, 44 Stat. 1162 (1927).

- See Slotten, supra note 58 , at 43.

- 68 Cong. Rec. 2580 (1927) (statement of Sen. Wallace H. White, Jr.) (“We have recognized in that compromise provision that it is not the right of a community to demand a station, not a right of a particular State to demand a station, but it was the right of the entire people to service that should determine the distribution of those stations; and it is written here in express language that it shall be the duty of this commission, this regulatory authority, to make such a distribution of stations, licenses, and power as will give all the communities and States fair and equitable service, and that is the sound basis on which legislation of this character should be founded.”).

- Hoover’s remarks were distributed to Congress during debate. In it, Hoover outlined a national plan for broadcast access. See id. at 2576 (statement of Sen. Edwin L. Davis) (“I am advised, Secretary Hoover, that the best broadcasting service can be rendered to the whole country by a few large stations. However, such a view utterly ignores the rights of the different sections and the desire of the citizens of different sections to have information and other programs of a sectional, State, or local character broadcast.” (emphasis added)).

- Radio Act of 1927, 44 Stat. 1162, 1167 (1927) (emphasis added).

- Amy Norcross, Hoover Joins 1st American Demo of Long-Distance TV, April 7, 1927, EDN (Apr. 7, 2019), https://www.edn.com/hoover-joins-1st-american-demo-of-long-distance-tv-april-7-1927/ .

- Id.

- See id.

- See id.

- Id.

- Suzanne Deffree, 1st American TV Station Begins Broadcasting, July 2, 1928, EDN (July 2, 2019), https://www.edn.com/1st-american-tv-station-begins-broadcasting-july-2-1928/ .

- Roosevelt’s speech was delivered at the New York World’s Fair in 1939. In contrast to his famous “fireside chats” on national radio and President Truman’s first televised address from the White House in 1947, this early broadcast only reached receivers at the Fair and in Manhattan. Harry Truman Delivers First-Ever Presidential Speech on TV, History, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/first-presidential-speech-on-tv (last updated Oct. 2, 2021).

- See Our History, NBCUniversal, https://www.nbcuniversal.com/history (last visited Feb. 24, 2021) (discussing NBC’s television beginnings in the early 1930s); Ed Reitan, CBS Color Television System Chronology, Novia, (2006), https://web.archive.org/web/20130922013759/http://www.novia.net/~ereitan/CBS_Chronology_rev_h_edit.htm (discussing CBS’ early experimentations with television in 1940); Keith Gluck, The Genesis of Disney Television, Walt Disney Family Museum (July 23, 2013, 2:00PM), https://www.waltdisney.org/blog/genesis-disney-television (discussing Walt Disney’s early investment in television in late 1935).

- See S. Comm. on Interstate Com., 73d Cong., Study of Communications by an Interdepartmental Committee: Letter from the President of the United States to the Chairman of the Committee on Interstate Commerce (Comm. Print 1934).

- Id.at 6 (emphasis added).

- Communications Act of 1934, 47 U.S.C. § 151 (1934).

- Id.(emphasis added).

- See id. (discussing the consolidation of communications policy authority to the FCC).

- Staff of the Fed. Comm. Comm’n, BC Docket No. 78-253, Report and Recommendation in the Low Power Television Inquiry, 5 (1980).

- See id.

- Adam Lefky, Number of Televisions in the US, Physics Factbook (2007), https://hypertextbook.com/facts/2007/TamaraTamazashvili.shtml (citing figures from The World Book Encyclopedia).

- Id. (citing figures from The Encyclopedia Americana).

- Id. (citing figures from The World Book Encyclopedia).

- Staff of the Fed. Comm. Comm’n, supra note 99, at 5.

- See I Love Lucy: An American Legend, Libr. of Cong., https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/i-love-lucy/legacy.html (last visited Feb. 24, 2021) (providing a timeline for “I Love Lucy,” beginning in the early 1950s); David B. Wilkerson, The Hunt for TV’s Lost Baseball Treasures, MarketWatch (Oct. 27, 3:36PM), https://www.marketwatch.com/story/the-hunt-for-tvs-lost-baseball-treasures-2010-10-27 .

- Staff of the Fed. Comm. Comm’n, supra note 99, at 5.

- Id. at 107.

- Id. at 107-08.

- Richard Burton, Interview with Leroy “Ed” Parsons, The Cable Ctr.: The Hauser Oral Hist. Project (June 19, 1986), https://www.cablecenter.org/programs/the-hauser-oral-history-project/p-q-listings/leroy-ed-parsons.html .

- See id.

- See id.

- Id.

- See id.

- Cablefax Staff, Ed Parsons Brings Cable to Astoria, Cablefax (2015), https://www.cablefax.com/cablefax_viewpoint/ed-parsons-brings-cable-astoria .

- See id.

- Id.

- Id.(“Ed said he never really made any money in cable television because it did not occur to him that he could turn it into a steady income. . . . Ed charged an installation fee based on his expenses, typically $125, but it did not occur to him to charge a monthly fee for his service.”).

- Loran Rasmussen, Interview with Robert Tarlton , The Cable Ctr.: The Hauser Oral Hist. Project (June 27, 1986), https://www.cablecenter.org/programs/the-hauser-oral-history-project/t-v-listings/robert-tarlton-penn-state-collection.html.

- See id. (“I designed so that we’d figure, well, about 200 people can afford to buy service and that’s what I designed the thing for. Little did I know within a month’s time the 200 people would be compounded. People clamoring for service.”). Tartlon charged a $100 installation fee with a $3/month maintenance fee.Id.

- The Cable History Timeline, The Cable Ctr. 1, https://www.cablecenter.org/images/files/pdf/CableHistory/CableTimelineFall2015.pdf (last visited Feb. 24, 2021).

- Staff of the Fed. Comm. Comm’n, supra note 99, at 6 (“According to E.B. Craney, a pioneer in the field of low-power television, the first booster probably was established in 1948, by Ed Parsons to reach homes beyond the range of his cable TV system in Astoria.”).

- Id. at 4.

- Id.at 30 (“The earliest translators often were financed by individuals who wanted television service for themselves and found that other members of the community would provide contributions to help cover the operating costs.”).

- 18 Fed. Comm. Comm’n Ann. Rep. 107 (1952).

- K.M. Richards, Translators: The Complete

Story, UHF Television, http://www.uhftelevision.com/articles/translators.html [ https://web.archive.org/web/20190911011955/http://www.uhftelevision.com/articles/translators.html ].

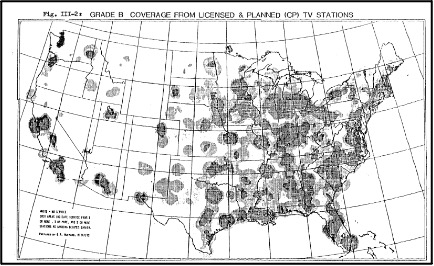

The below is the proposed channel allotment strategy in the Sixth Report and

Order:

Staff of the Fed. Comm. Comm’n, supra note 99, at 56.Population of Central City Number of Channels 1,000,000 and above 6 to 10 250,000 – 1,000,000 4 to 6 50,000 – 250,000 2 to 4 Under 50,000 1 to 2 - Richards, supra note 125.

- Radio Waves, Sci. Encyc. , https://science.jrank.org/pages/5675/Radio-Waves-Propagation-radio-waves.html (last visited Feb. 25, 2021).

- See Mark D. Casciato,Radio Wave Diffraction and Scattering Models for Wireless Channel Simulation 1(2001) (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan), http://www.eecs.umich.edu/radlab/html/NEWDISS/Casciato.pdf (“The propagation of a radio wave through some physical environment is effected by various mechanisms which affect the fidelity of the received signal. . . . These effects can include shadowing and diffraction caused by obstacles along the propagation path, such as hills or mountains in a rural area, or buildings in more urban environment.”).

- Staff of the Fed. Comm. Comm’n, supra note 99, at 38.

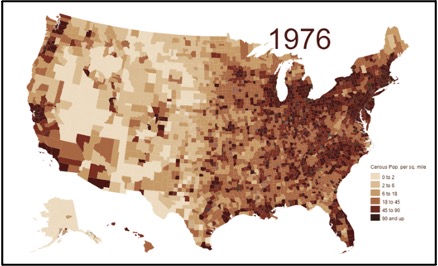

- Jeff Desjardins, Visualizing 200 Years of U.S. Population Density, Visual Capitalist (Feb. 28, 2019), https://www.visualcapitalist.com/visualizing-200-years-of-u-s-population-density/ (displaying an animated map created by Vivid Maps, based on U.S. census data and Jonathan Schroeder’s county-level decadal estimates for population).

- Hundreds of operations were erected as the decade passed. Cable Television, History of, Encyclopedia.com, https://www.encyclopedia.com/media/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/cable-television-history (last visited Mar. 31, 2021).

- See Burton, supra note 109 (Leroy “Ed” Parsons discussing the Jerrold amplifier in the 1950s, designed for retransmitting four channels simultaneously).

- During the 1950s, AT&T Long Lines built a transcontinental system of microwave relay links across the United States that grew to carry the majority of American television network signal traffic. “Sugar Scoop” Antenna Catches Microwaves, Popular Mechs., Feb. 1955, at 87. See also 1965 House Hearings, supra note 24 (statement of Ernest W. Jennes. Counsel, Maximum Service Telecaster, Inc.) (“There are no geographical bounds for ‘CATV unlimited.’ Increasingly, multi-hop microwave relays are being sought or planned to import stations from metropolitan centers across many hundreds of miles and several States.”).

- Staff of the Fed. Comm. Comm’n , supra note 99, at 7–8.

- One particular incident involved Governor Ed Johnson of Colorado—former Chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee—who issued an open challenge to the FCC to sue the state as he granted licenses to all persons seeking a booster license.Id.at 7. A similar incident involved an Oregon Senator who resisted the shutting down of a local booster operation in the Okanogan Valley. Id. at 6–7.

- See id. at 8.

- Robert Kastenmeier, Register of Copyright.

Ernest W.Jennes.

Actually, don’t the stations commercially benefit by this, in the sense that translator stations, booster stations, add to viewership? I would think that the stations involved whose signals were being thus picked up and translated would stand to benefit and be able to commercially improve their rate structure as far as advertising is concerned.”

1965 House Hearings, supra note 24, at 8.Well, if you take the situation—and we are talking apparently about translators now and not CATV systems—where the service is being provided by a translator, the extension of the service is being provided free. Where the stations is able to increase the number of people it serves by virtue of a translator, it is to that extent benefiting its own circulation. This is in sharp contrast to the CATV situation where you have outside signals being brought in by CATV into the areas served by the station and fractionating the audience of the station.