Sarah Sue Landau*

Download a PDF version of this article here.

Introduction

Mickey Mouse, the iconic mascot of the Walt Disney Company, is one of the most recognizable and beloved characters in the world.[1] Ever since his first appearance in 1928 in the cartoon Steamboat Willie,[2] Mickey Mouse has made his mark on popular culture appearing in cartoons,[3] movies,[4] video games, [5] “in person” at Disney theme parks,[6] and on almost every type of merchandise imaginable.[7] In fact, just recently, Mickey Mouse celebrated his 90th birthday in an extravagant televised prime time special.[8] However, from a copyright law standpoint, Mickey Mouse’s venerated old age has not been a cause of celebration for the Walt Disney Company. For years, intellectual property lawyers at Disney have approached the subject of Mickey Mouse’s aging with trepidation because the older Mickey Mouse gets, the closer the date gets to December 31, 2023—the date on which the copyright on Steamboat Willie expires. After that point, starting on January 1, 2024, Disney will begin to lose its exclusive right to Mickey Mouse as the Steamboat Willie version of Mickey Mouse will have fallen into the public domain.[9]

Some have suggested that the loss of this copyright would not make much of a practical difference because Mickey Mouse is also protected by trademark.[10] Unlike copyright, trademark protection does not expire and can continue indefinitely as long as a mark maintains its association with a source. Today, Mickey Mouse is undeniably associated with the Disney brand, and there is no indication that this will change any time in the future. As such, it would seem that the Mickey Mouse mark would maintain its trademark protection indefinitely.

However, a statement from a 2003 United States Supreme Court case, Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., suggests that using trademarks as a workaround for protecting expired copyrights is prohibited.[11] Specifically, the opinion reasoned that the Lanham Act was not meant to be used to extend expired copyrights since doing so “would create a species of mutant copyright law” that limits the public’s right to use expired copyrighted materials that have entered the public domain (emphasis added).[12]

Yet, while the Dastar court cautioned against the use of “mutant copyright[s],” it did not provide any practical guidance regarding how to address issues of overlapping copyright and trademark protection.[13] As such, lower courts have had little direction on how to implement Dastar when these issues arise. The Supreme Court has yet to clarify its decision, and Congress has not amended the Copyright Act to address the matter. Therefore, between now and 2024, the fate of Mickey Mouse remains uncertain.

This paper will analyze this Mickey Mouse dilemma in more depth. In particular, Part 1 of this paper will provide a brief overview of copyright protection in the U.S. and will explain the significance of new works entering the public domain in the modern era. Part 2 will provide an overview of trademark protection. Part 3 will touch upon the problem of overlapping protection as illustrated through the example of Mickey Mouse. Finally, Part 4 will propose and examine possible solutions.

I. The History of Copyright and “the Copyright Bargain”

Moments before midnight on December 31, 2018, over a million people stood shivering in the cold in Times Square as they counted down the seconds until the ball dropped, thus officially ringing in the New Year.[14] As in years past, the emergence of a New Year elicited excitement, fireworks, displays of affection, and New Year’s resolutions. However, 2019 would be different. The arrival of January 1, 2019 was of particular significance to American copyright law because, on that historic day, all copyrighted works from the year 1923 officially entered the public domain—a phenomenon, the likes of which had not occurred in 20 years.[15] To understand the significance and implications of this occasion, it is necessary to review the history of and rationales behind U.S. copyright law.

The traditional rationale given for U.S. copyright law is utilitarian[16] and is reflected in the U.S. Constitution, which grants Congress the power “to promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.”[17] Congress’s power to administer copyrights can be thought of as a “copyright bargain” since it enables Congress to simultaneously incentivize innovation while avoiding the granting of unlimited monopolies.[18] Additionally, the copyright system provides a mechanism for weighing the interests of rewarding artists for their work while also providing society at large with raw materials for future creative works.[19] Congress uses copyright law to protect authors (artists, producers, etc.) for a limited time period from having others copy or use their work without permission.[20] Once that designated period has passed, the works enter the public domain where they may be used, copied, changed, or adapted by anyone for free without any compensation to the original author or copyright holder.

Over time, the subject matter of what can be protected by copyright has expanded.[21] While the original Copyright Act of 1790 only applied to maps, charts, and books,[22] the current copyright statute applies broadly to “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression,” including literary works; musical works; dramatic works; pantomimes and choreographic works; pictorial, graphic and sculptural works; motion pictures and other audiovisual works; sound recordings; and architectural works.[23] Case law that interpreted these listed categories expanded upon them. For example, some courts have concluded that some cartoon characters[24] and corporate logos[25] may be copyrightable as “pictorial, graphic and sculptural works.”

Under the 1976 Copyright Act, protection begins as soon as the artist “fixes” an “original work,” rather than at the time of publication.[26] Registration is not required,[27] and protection lasts 70 years after the author’s death. However, this was not always the case.[28]

The initial 1790 Copyright Act protection lasted 14 years from publication and was renewable for another 14 years, for a maximum of 28 years.[29] Congress increased the length of copyright protection with each subsequent iteration of the Copyright Act in 1831, 1870, and 1909.[30] The 1976 Copyright Act greatly extended it to the length of the life of the author plus an additional 50 years or a total of 75 years for corporate authorship.[31] In the 1998 Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA), Congress gave into the pressure of lobbyists (primarily Disney lobbyists who were hoping to extend the protection of Mickey Mouse)[32] and once again extended this term an additional 20 years, totaling the life of the author plus 70 years (or for a work made for hire—120 years after creation or 95 years after publication, whichever is earlier).[33] As a result of the CTEA, works that were set to go into the public domain in 1999 were “frozen” for another 20 years. No works entered the public domain between 1999 and 2018. While there was speculation that lobbyists might try to further delay and convince Congress to pass an additional Extension Act, this did not occur.[34] Therefore, as of January 1, 2019, works of famous authors, filmmakers, and musicians from the year 1923, such as Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments,[35] Charlie Chaplin’s The Pilgrim,[36] and Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan and the Golden Lion,[37] finally entered the public domain just as creative works used to do every year prior to 1998.[38] Barring a change in the laws, works will continue to enter the public domain in each successive year.[39] Therefore, in under four years from now, on January 1, 2024, Mickey Mouse, too, will enter the public domain.[40] It will be followed in subsequent years by many of Disney’s other classic films including Snow White and the Seven Dwarves[41] (in 2027), Pinocchio[42] (in 2030), Fantasia[43] (in 2030), Dumbo[44] (in 2031), Bambi[45] (in 2032), and Cinderella[46] (in 2040).[47]

In his article The New Public Domain, Professor Joseph Liu, argues that things might not proceed so simply.[48] He contends that the “new public domain,” works that will enter the public domain after 2019, is different from the simplicity of the public domain of the past, which contained works that entered the public domain prior to 1998, and is therefore likely to be treated differently by copyright holders. This is because the types of works entering the public domain today are different.[49] Because of the CTEA, the works entering the public domain in 2019 were created in 1923 and thus largely consisted of literature, music (in the form of public performance or sheet music), and early black and white silent films.[50] However, shortly after 1923, creative works began to take on new and more sophisticated forms, due to technological developments in the music and film industries that were made possible by the invention of radio and introduction of colored full-length movies with sounds.[51]

Additionally, since 1998, technologies of dissemination have greatly improved.[52] With the rise of the Internet, the availability of streaming services, and the ability to instantly download almost anything digital, a work entering the public domain today means something very different than it did in 1998. Today, as soon as a work is made public, it can immediately be uploaded to the Internet and added to any website, including Google books, Amazon, Facebook, YouTube, Hulu, Netflix, etc. and be instantly accessible to the public at little to no cost. Moreover, if one wanted a physical printed copy of a literary work, there are many online publishing services and an abundance of copy shops that one has easier access to than one might have had in 1998.

Furthermore, the average person in 2020 has more technical prowess than one probably thought possible in 1998. Most people today have smart phones and/or personal computers. Through user-friendly applications, such as Photoshop,[53] Garageband,[54] Final Cut Pro,[55] and even Instagram filters, every-day individuals, rather than only experts, are easily able to use raw public domain materials to manipulate and create new works.

Liu argues that these observations lead to the conclusion that the public domain will become increasingly important in upcoming years and will likely shift the balance of the copyright bargain towards the public and away from the copyright holders.[56] While this shift might be exciting for the public and lead to more creativity overall, Liu argues that it may cause concern for copyright holders, likely leading them to turn to other overlapping intellectual property areas—such as trademarks—for protection instead.[57]

II. Trademark Protection

Unlike copyright protection, which expires after a limited period of time, trademark protection can be indefinite. As such, it would seem to be a reasonable strategy for copyright holders to try to claim trademark protection for their works as well. However, while there is certainly overlap, trademark is a separate area of law from copyright, with different objectives and requirements. This discussion will focus on statutory trademark protection, although state common law trademark protection is also available in some circumstances.[58]

For instance, although it may inadvertently do so, trademark law, unlike patent and copyright law, is not meant to foster innovation. As usually described, the goal of trademark protection is to constrain unfair competition[59] and to limit search costs for consumers seeking to identify products with their sources.[60] By marking a product in a uniquely identifiable way (in a “distinctive” way), it signals to consumers that the product was made by a specific brand and therefore embodies certain qualities or will deliver a certain experience associated with that brand. For instance, when a consumer purchases a laptop with the Apple logo on it, the logo serves as an indicator that the laptop will be of the quality and functionality associated with other Apple devices. If the laptop were to have a Windows logo on it instead, a different set of assumptions would be warranted. Being able to make these assumptions allows consumers to make quicker and more efficient purchasing decisions.

Based on this rationale, there is no reason to limit the duration of trademark protection since marks serve this “minimizing search costs” function as long as they are being used. Thus, trademark protection under the Lanham Act can be indefinite so long as a mark holder can continue to show that his or her marks meet the requirements of a trademark—that the mark has acquired or inherent distinctiveness,[61] is non-functional,[62] and continues to be used in commerce.[63]

However, exactly what is considered a trademark under the law is quite broad and continues to expand as courts interpret the Lanham Act. The most common types of trademarks are logos and brand names, but U.S. trademark protection also covers colors, smells, sounds, product design, and product configuration.[64] For example, some trademarks include the name Apple for computers,[65] the color red for the bottom of Christian Louboutin shoes,[66] the smell of Play-Doh,[67] the sound of Tarzan’s yell,[68] the interior of the Apple store,[69] and even the shape of the Coca-Cola bottle.[70]

Under American trademark law, the use of a mark in commerce entitles a mark holder to protection. Therefore, as with copyright law, registration of a trademark is not required to gain protection. Despite this, many choose to register anyway because registration provides additional benefits, such as nationwide priority even if the mark has not yet been used throughout the nation,[71] a prima facie presumption of validity,[72] and the possibility of reaching incontestable status after five years of continuous use.[73] Additionally, one has the option of registering a trademark on an “intent to use” basis[74] so one can benefit from registration prior to actual use.

Because the goal of trademark law is to reduce consumer search costs and make it easy for consumers to associate products with their sources, the Lanham Act does not prohibit infringers who copy or make unauthorized uses of a mark simply because it is the property of someone else. Instead, the Lanham Act protects against infringing marks that cause confusion with or dilution of the mark holder’s mark and in doing so reduce the ease with which consumers can make the proper product-source association. The mark holder of a registered or unregistered mark can bring a claim under the Lanham Act if he or she can prove that an infringing mark will cause a likelihood of consumer confusion or dilution.[75]

Each circuit has its own slightly different test, but generally speaking, to prove that an infringing mark will cause a likelihood of confusion, the plaintiff may try to prove the following factors: 1) that the mark is strong; 2) that there is a high degree of similarity between the two marks; 3) that the two products being compared are proximate and that the plaintiff might try to bridge the gap; 4) actual confusion by consumers; 5) that the defendant acted in bad faith; and 6) that the defendant’s product is of differing quality and that the buyers are unsophisticated.[76] These factors are non-exhaustive, and courts may take other variables into account as well.[77]

To make a claim for dilution, that is, to show that the infringing mark causes “damage to the positive associations or connotations of [the mark holder’s] trademark,”[78] a plaintiff must show, “1) that the plaintiff owns a famous mark that is distinctive; 2) that the defendant has commenced using a mark in commerce that allegedly is diluting the famous mark; 3) that a similarity between the defendant’s mark and the famous mark gives rise to an association between the marks; and 4) that the association is likely to impair the distinctiveness of the famous mark or likely to harm the reputation of the famous mark.”[79]

With this background in mind, Mickey Mouse is undeniably trademarked and thus merits indefinite protection. Both the Mickey Mouse name and image are highly distinctive, and it is nearly impossible for consumers to hear Mickey’s name or see his image without making the association with the Disney brand. While trademark registration is not required to get protection, Disney has chosen to register many different versions of the Mickey Mouse mark with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). For instance, Disney owns the word mark for the stylized words “Mickey Mouse,”[80] various marks featuring the more “classic” version of Mickey Mouse,[81] marks featuring the modern image of Mickey Mouse,[82] and even a mark featuring the evolution of Mickey Mouse over time.[83] As long as Disney does not abandon these marks and its other unregistered marks, and continues to use them in commerce, they will have indefinite trademark protection. Furthermore, Disney’s claims to its various Mickey Mouse trademarks are bolstered by the fact that Disney has sued infringers over the Mickey Mouse mark several times and has been successful in court, providing a body of case law precedent for the strength of the Mickey Mouse mark as well.[84]

III. The Problem

Professor Viva R. Moffat suggests that Mickey Mouse (and other characters)[85] have been afforded both copyright and trademark protection as a result of the expanding nature of copyright and trademark laws.[86] In her article Overlapping Copyright and Trademark Protection: A Call for Concern and Action, Professor Irene Calboli explains that dual protection is unsurprising given both trademark’s and copyright’s inherent emphasis on creativity.[87] To be granted copyright protection, the Copyright Act requires works to be “original.” Courts have interpreted originality to mean that works must be independently created and contain a modicum of creativity.[88] A work lacking in creativity cannot receive copyright protection. Similarly, trademark law also subtly favors marks that are more creative in a different way. Under trademarks doctrine, marks that are “arbitrary,”[89] “fanciful,”[90] or “suggestive”[91] are considered inherently distinctive and do not require a showing of secondary meaning to be protected.[92] Such marks embody a creative element since they require the consumer to make an association between the mark and source that is not immediately obvious. Conversely, marks that are “descriptive”[93] (and less creative) do require a showing of secondary meaning in order to acquire distinctiveness. Moreover, marks that are “generic” (and by extension, completely uncreative) are ineligible for trademark protection.[94] In this sense, “even though copyright and trademark protection are different in scope and follow different rules, their normative foundations conceptually overlap in their aspects of originality (the sine qua non for copyright protection) and of distinctiveness (the sine qua non for trademark protection . . .)”[95] Further, trademark law’s goals do not relate directly to innovation, simply from a business standpoint. Still, marketing professionals today must invest creativity in the process of creating a brand’s image and designing a company’s trademarks in order to find new ideas that have not already been used[96] so they can stand out from competitors and avoid the risk of being considered confusingly similar to other marks. Calboli argues that, due to this emphasis on creativity, the lines between copyright and trademark have blurred, “precisely with respect to creative elements that can be defined as both creative and distinctive—such as characters, graphical elements, pictures, video clips and songs.”[97]

At first glance, overlapping protection is not inherently problematic. Some might argue that the greater coverage afforded to works by overlapping protection has led to more innovation on the copyright side and fewer search costs on the trademark side, leaving everyone better off overall. Furthermore, being protected by both the Copyright Act and the Lanham Act provides plaintiffs with additional possibilities of remedies in the event of infringement. As such, it is unsurprising that plaintiffs in infringement cases frequently advance both theories.[98]

But the counter to this argument is that allowing for dual protection and the possibility of a wide menu of remedies in the event of breach may be unfair to defendants. Additionally, it would seem that overlapping protection could be particularly problematic and create uncertainty in the situation where copyright protection expires but trademark protection persists.

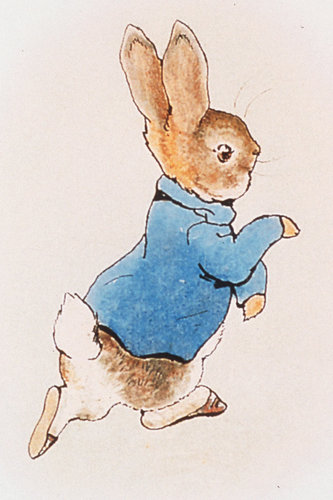

Courts have gone back and forth on this issue over time. In 1979, the Second Circuit suggested that overlapping copyright and trademark protection was no cause for concern. In Frederick Warne & Co. v. Book Sales, Inc., the court addressed the question of overlapping protection regarding an image of the famous children’s story character, Peter Rabbit.[99] The plaintiff, the publisher for Beatrix Potter’s Peter Rabbit books, argued that the defendant’s newly published book, a collection of Peter Rabbit stories, which featured an image of Peter Rabbit found in Beatrix Potter’s illustrations, infringed on its trademark. The defendant argued that he had done nothing wrong since the Peter Rabbit books and illustrations had fallen into the public domain before he had used them.[100] The court sided with the plaintiff, finding that, “[t]he fact that a copyrightable character or design has fallen into the public domain should not preclude protection under the trademark laws so long as it is shown to have acquired independent trademark significance, identifying in some way the source or sponsorship of the goods. . . . Because the nature of the property right conferred by copyright is significantly different from that of trademark, trademark protection should be able to co-exist, and possibly to overlap, with copyright protection without posing preemption difficulties.”[101]

However, years later, in 2003, the Supreme Court seemed to reject this reasoning in Dastar and argued that granting trademark protection after a copyright has expired should not be allowed since it undermines the rationales behind copyright and disrupts the copyright bargain.[102] In Dastar, the plaintiff, 20th Century Fox, owned the copyright to a TV series based on a book written by President Eisenhower about Europe during World War II.[103] Fox inadvertently failed to renew its copyright in the TV series and, as such, the TV series copyright fell into the public domain. At that point, Dastar, the defendant, decided to slightly edit and use the public domain footage. Dastar sold it and presented its version as its own without any mention of Fox. Fox then sued Dastar for “reverse passing off”— the misrepresentation of another’s goods as one’s own—in violation of § 43(a) of the Lanham Act.[104] Lanham Act § 43(a) allows a mark holder to bring a civil action against one who uses an infringing mark in a way that “is likely to cause confusion, or to cause mistake, or to deceive as to the affiliation, connection, or association of such person with another person, or as to the origin, sponsorship, or approval of his or her goods, services, or commercial activities by another person” (emphasis added).[105] The court held that the “origin” of the goods in question was actually Dastar rather than Fox or even Eisenhower, since Dastar produced the product actually being sold to consumers.[106] By holding this way, the court was able to find that Dastar did not infringe on any trademark and also expressed its opposition towards considering an expired copyright holder to be an “origin” of the good at all. The court explained that, “allowing a cause of action under § 43(a) . . . would create a species of mutant copyright law that limits the public’s federal right to copy and to use expired copyrights.”[107] In other words, using trademark law to extend protection once a copyright has expired unfairly limits the public’s right to use materials that should be considered part of the public domain.[108]

A prime example of this concern is Mickey Mouse. As previously mentioned, the original copyright for Mickey Mouse dates back to 1928 with the release of Steamboat Willie. Since then, Mickey Mouse has become trademarked, since it has acquired distinctiveness and has come to be a strong source indicator for Disney. When Mickey Mouse’s copyright expires in 2023, this will put the Steamboat Willie version of Mickey Mouse into the public domain. At that point, everyone may use the version of Steamboat Willie Mickey Mouse in their artwork, stories, videos, social media profile pictures, etc. and Disney will have no recourse under copyright law.

However, mainstream public use of Mickey Mouse’s image will certainly conflict with Disney’s Mickey Mouse trademark. Perhaps because of this issue, Disney has preemptively done its best to incorporate the Steamboat Willie version of Mickey Mouse into the modern-day brand. They continue to show Steamboat Willie on their website,[109] sell Steamboat Willie merchandise through their store,[110] make references to Steamboat Willie in other works,[111] and even use the iconic Steamboat Willie image as part of their logo for Disney Animation Studios.[112]

Due to these efforts, consumers are likely to assume that Disney endorsed any product featuring Steamboat Willie and will most certainly continue to associate such paraphernalia with the Disney brand for years to come. For this reason, it would seem that Disney has every right to sue users of the Steamboat Willie Mickey Mouse image under a trademark infringement theory.

Yet under the Dastar precedent, it seems that Disney would fail in this endeavor. The purpose of the copyright bargain is to allow works to eventually enter the public domain, and if trademark law were to persist here, it would inhibit the copyright bargain. Yet, it is also unclear as to why the rationale for copyright should prevail over the rationale for trademark protection. Surely, Disney has invested a large sum in using Mickey Mouse to build its brand and help consumers minimize search costs. This is precisely the kind of behavior that trademark law is usually meant to incentivize, and for which there is no protection end date. Dastar does not specifically address or comment on this reasoning.

As the Supreme Court did not provide any practical guidance on how to implement Dastar, overlapping protection is still quite an open and undecided area of law. Since many popular works, including Mickey Mouse, will enter the public domain within the next few years, it is clear that the Supreme Court or Congress needs to address the issue.

IV. Solutions

The remainder of this paper will explore some proposals of ways that Congress and/or the Supreme Court might address the issue, including: 1) amending the duration of protection in the Copyright Act or the Lanham Act, 2) allowing the works to fall into the public domain, 3) using false advertising law, and 4) creating stronger channeling doctrines.

A. Proposal #1: Amend the Lanham Act in order to impose a time limit on marks whose copyrights have expired

Until recently, Congress arguably chose to address the issue of overlapping protection through avoidance. Congress never set out clear instructions on how to handle expired copyrights that receive trademark protection, and the CTEA’s 20 year delay of many characters’ entry into the public domain effectively deferred the issue.[113] However, Professor Moffat argues that the CTEA did more than just delay a resolution of the issue and that it actually exacerbated the problem because it gave companies like Disney time for their trademarks to acquire secondary meaning, and thereby to become more powerful.[114] Certainly, during the past 20 year copyright freeze, Disney took advantage of Mickey Mouse’s continued protection and undertook countless marketing,[115] branding, and legal initiatives to strengthen the Mickey Mouse trademark.[116]

For this reason, an additional extension of the copyright term would not be advisable, and perhaps Congress realized this since it chose not to extend the copyright term in 2019 when the CTEA protection expired for works from 1923. However, the issue of overlapping protection must still be addressed.

Instead of amending the Copyright Act and dealing with the issue through copyright law, Congress could address the issue through trademark law. One possible solution to the problem of overlapping protection would be to amend the Lanham Act by adding a section specifically addressing marks whose copyrights have expired. For example, a rule which places a time limit on such marks and allows a trademark to be enforced for an additional, fixed number of years past the expiration of its copyright, after which the trademark would expire as well, would allow characters like Mickey Mouse a period of time in which they could benefit from both copyright and trademark law individually without running into the risk of becoming a “mutant” eternal copyright.[117] This solution could be compatible with the copyright bargain, since the works would eventually enter the public domain. Additionally, it would also help to achieve some of the goals of trademark because it would give the company a period of time where the marks would be protected, and consumers could rely on the association of the mark with a particular source.

Yet, this compromise is not perfect, as it does not directly address the fact that under trademark theory, protection should be indefinite. In her article, The Methuselah Factor: When Characters Outlive Their Copyrights, Professor Leslie Kurtz argues that part of the difficulty with characters is that they do not fit neatly into trademark doctrine to begin with.[118] While one goal of trademarks is to identify the source of a good, in the case of characters, Kurtz argues that, “a character’s ability to identify a single source may be no more than a convenient fiction.”[119] Unlike logos, such as the Starbucks logo, which signifies that drinks bearing the logo come from the Starbucks Company, characters do not provide as clear of a source. Kurtz explains,

What is the source of a fictional character? Is it the author or publisher of a book; the director or producer of a film? What if a character appears in a book and a film? Is the source the book’s author, the book’s publisher, the film’s director, or the film’s producer? . . . There is a tendency to focus on the character itself, rather than on any information it provides about source or identification.[120]

Additionally, Kurtz argues that characters do not meet trademark’s goal of minimizing search costs through signifying that goods bearing the mark are of consistent quality.[121] She explains, “[c]onsumers buy Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles clothing or ‘E.T. Phone Home’ mugs not because the symbol indicates that the shirt is of a certain quality or the mug won’t break, but because they want that picture or that phrase on their merchandise.”[122]

Yet this critique could extend to trademarks generally. Consumers may buy a Nike t-shirt simply to display the Nike swoosh logo across their chest, with little thought to the quality of the shirt itself. In fact, some have criticized trademarks as creating “artificial product differentiation” since consumers are likely to pay more for a shirt with a popular logo than for a shirt of identical quality without one.[123]

Regardless, it is clear that characters do have some unique characteristics that other trademarks do not. Therefore, rather than broadly limiting the Lanham Act to restrict any mark whose copyright has expired, perhaps it makes sense to narrow the parameters and only place a time limit upon characters being used in logos or as part of the brand, whose copyright has expired. If, as Kurtz says, it is a stretch for characters to receive trademark protection in the first place, then placing a time limit just on characters might be less problematic under the Lanham Act.

B. Proposal #2: Allow the Characters to Fall Into the Public Domain

While Disney would certainly be upset, an additional plausible option to address the issue is simply to do nothing and to let copyrighted works fall into the public domain.

Kurtz argues that “[f]ictional characters help form the modern myths out of which we operate and are an important part of the cultural heritage on which an author can draw to create something new. They can encapsulate an idea, evoke an emotion, or conjure up an image. When a fictional character has entered the public domain, there are strong policy reasons for keeping it there, thus allowing others to make use of it.”[124] Keeping works in the public domain is the best way to adhere to the copyright bargain and to protect against monopolies. Additionally, as Professor Jessica Litman points out, “Mickey Mouse has enjoyed a long, and very lucrative, run. If it is time to close the show, it has more than paid back its investment.”[125] Therefore, despite the outcry from Disney, it would not be horrific if Mickey Mouse were available for all to use.

In fact, Mickey Mouse would not be the first major character to fall into the public domain. Sherlock Holmes provides an illustrative example of an iconic fictional character that has fallen into the public domain without catastrophic consequences. Today, Sherlock Holmes books, movies, and TV shows continue to be written, borrowing the character from Arthur Conan Doyle’s iconic series, and the consent of the Arthur Conan Doyle estate is not required.[126] However, it was not always clear that it would be this way.

The use of Sherlock Holmes was initially met with resistance. In Klinger v. Conan Doyle Estate, Ltd., the Conan Doyle estate argued that Sherlock Holmes should not be in the public domain until the totality of the series had fallen into the public domain.[127] The Court disagreed and held that since most of the books were written prior to 1923, they were in the public domain.[128] However, they found that certain plot elements included in Sherlock Holmes short stories written after 1923, such as the existence of Dr. Watson’s second wife, Dr. Watson’s background as an athlete, and Sherlock Holmes’ retirement from his detective agency, had not yet fallen into the public domain.[129] Therefore, these elements may not be used in modern adaptations until they, too, expire and enter the public domain.

Similar reasoning can be applied to Mickey Mouse. When the copyright expires for the Steamboat Willie version of Mickey Mouse, it will fall into the public domain. However, later versions of Mickey Mouse will be protected until their copyrights expire.

Yet, the analogy between Sherlock Holmes and Mickey Mouse is not perfect. While Doyle could only write so many books before he passed away, Disney, as a company, can (and has) continuously updated Mickey Mouse over time, slightly changing his appearance thus maintaining his relevance for new generations (and generating new copyrights in the process).[130] This also has interesting ramifications for trademarks.

In trademark law, there is a concept called tacking, whereby trademarks, which are slightly updated over time, but are still recognized as creating “the same, continuing commercial impression,” can be considered the same mark and refer back to the initial registration when determining the registration date.[131] Although tacking is mainly used to determine the date of registration, which is important when a trademark is contested, the idea that trademarks can develop over time yet essentially remain the same mark is particularly relevant here. If some sort of tacking logic is applied to Mickey Mouse, then even once a copyright expires, Mickey Mouse’s trademark protection could effectively remain indefinite. However, the Supreme Court has noted that tacking only applies in “exceptionally narrow” circumstances.[132] Even without tacking, a company could have multiple trademarks in effect at any given time, as long as the marks remained in use in commerce and continued to be associated with the source.

Yet the question still remains, if a copyright expires, practically speaking, how could we continue to enforce trademark rights without running into conflicts between the goals of the two intellectual property regimes?

The Frederick Warne court argued that the property rights afforded by trademark and copyright were significantly different[133] and therefore implied that the line could be drawn based on the way that a character was being used. For example, if a character were to be used in an artistic way, such as in a painting, movie, or book, that would clearly be a copyright use and would not be considered infringement after the work falls into the public domain. If, however, a mark is being used to identify its source, such as being placed as a logo and being sold on a lunchbox, then it is being used in the trademark sense, and in that situation, infringers could be liable for trademark infringement.

Professor Jane C. Ginsburg uses the example of the Cat in the Hat to describe this distinction.[134] She explains, “[t]he Cat, the character, stars in two eponymous children’s stories,” and “[t]he Cat, the brand . . . adorns the spines and front and back covers of the books in the Beginner Books ‘I Can Read It All By Myself’ series of children’s books.”[135] She continues: “When the Dr. Seuss books fall into the public domain, anyone may republish them, but the subsistence of trademark rights in the Cat as part of the trade dress of the Random House book series means that any unlicensed versions of that image of the Cat may not appear on the spines, back covers, or upper right hand corners of the front covers of those republications.”[136] She analogizes the Cat in the Hat to Mickey Mouse and says that there is no reason why “Steamboat Willie, the brand, should [not] remain distinct from Steamboat Willie, the character.”[137] However, this analogy between the Cat in the Hat and Mickey Mouse is not perfect. The “I Can Read It All By Myself” series uses the Cat in the Hat logo in a very specific way, in predictable places on the spines and backs of books, whereas the Steamboat Willie mark manifests itself in different ways and is used in many different contexts.

While it is unclear if this difference would be material, practically speaking, Ginsburg’s proposal still faces the objection that it can be confusing to draw the line between acceptable copyright uses of a character and unacceptable trademark uses. Surely the public is unlikely to know which versions of Mickey Mouse are in the public domain, and because Mickey Mouse has acquired an enormous amount of secondary meaning, even if an artist tries to use Mickey Mouse in a purely artistic and non-commercial sense, the public will likely still assume that Disney is involved. Furthermore, there are instances where this line will blur. For instance, what if a street artist makes a mural of Mickey Mouse, but then Disney decides to sell postcards of the mural? Would that be considered a copyright use of Mickey Mouse or a trademark use?

Kurtz argues that the best way to handle the confusion between copyright and trademark is through the use of disclaimers.[138] To prevent this confusion at the outset, Kurtz proposes that those who do not have trademark rights be required to visibly indicate “not an authorized use.”[139] Alternatively, the trademark holder might be required to somehow indicate that something is a trademarked use. This solution is interesting and may craft a system, similar to the art world, where authenticity matters more than what is actually displayed in the work itself. An authentic, authorized Mickey Mouse lunch box could be worth much more than an unauthorized lunchbox. However, this system hinges on people reading and understanding disclaimers. If a company has a very discrete small logo, like the tiny polo man on Ralph Lauren polo shirts, for aesthetic reasons, it may not want to have to use space indicating that something is an authorized use. Perhaps these indications could be made through some sort of small symbol, like the ® or ™ signs. However, unlike the ® and ™ signs, the symbol used would have to be broadly understood by the general public, and building up that understanding would require time and money to educate.

While this solution certainly provides some food for thought as to how trademarks could be used in a world when copyrights expire, some might argue that it disregards the Supreme Court’s decree in Dastar that trademarks not be used to extend protection once copyright expires. This is unsurprising since Kurtz’s article was written prior to the Dastar opinion. But at the end of the day, Dastar is Supreme Court precedent, and therefore, it cannot be completely ignored when implementing a solution.

Of course, the courts could limit the holding of Dastar to the very specific facts of the case. For instance, one could say that the holding about avoiding mutant copyrights only applies in the limited situation of reverse passing off when someone accidentally forgets to renew a copyright. Reading Dastar in this way would remove a lot of its power, but that was probably not Justice Scalia’s intention and may not be the wisest approach.[140] Alternatively, as we have seen in many Supreme Court cases, a future Supreme Court may take the line about “mutant copyrights” and say that it was merely dicta and not the holding. Only time will tell, and it will be up to the Supreme Court to maneuver out of past precedent, but until then, we can only guess at how Dastar should best be applied with the text that we have.

C. Proposal #3: Use false advertising law instead of trademark law in order to get around Dastar

Although Dastar does not permit the use of trademarks as a means of extending protection after copyrights expire, the Dastar opinion does leave room for the possibility of using false advertising law as a means of protection instead. At the end of the Dastar decision, the court explains that if a copied worked were used “in advertising or promotion, to give purchasers the impression that [it] was quite different” than the original that it copied “then . . . the respondents might have a cause of action . . . for misrepresentation under the ‘misrepresents the nature, characteristics [or] qualities’ provision of § 43(a)(1)(B).”[141] This refers to Lanham Act § 43(a)(1)(B), often called the false advertising prong,[142] which holds liable in a civil action “any person who, on or in connection with any goods or services, or any container for goods, uses in commerce any . . . false or misleading description of fact, or false or misleading representation of fact, which in commercial advertising or promotion, misrepresents the nature, characteristics, qualities, or geographic origin of his or her or another person’s goods, services, or commercial activities” (emphasis added). [143] As it has been interpreted, “nature, characteristics, and qualities” refers to the nature of the good itself, rather than a question about the authorship or source of the good.[144]

As it applies to Mickey Mouse, this means that a false or misleading promotion made about Mickey Mouse’s “nature, characteristics, or qualities” might qualify for a false advertising claim, but a claim about the author of Mickey Mouse would not. For instance, if a non-Disney entity was selling Mickey Mouse products and was advertising Mickey Mouse’s tendency to be the villain, his superpower of teleportation, his connection to his girlfriend Daisy Duck, or his famous triangular shaped ears, any of these might be false advertising. However, Disney would not have a claim against a seller who simply sold Mickey Mouse paraphernalia without accreditation to Disney or who even took Disney gear and sold it under its own brand, since these are examples of passing off and reverse passing off, which are seemingly barred by Dastar.

To make matters more complicated, the requirements for false advertising are different from regular trademark protection. Rather than just needing to show a likelihood of confusion (necessary for a trademark infringement claim), to have a valid false advertising claim, a plaintiff must demonstrate that: “(1) the defendant’s statements were false or misleading; (2) the statements deceived, or had the capacity to deceive, consumers; (3) the deception had a material effect on consumers’ purchasing decision; (4) the misrepresented service affects interstate commerce; and (5) the plaintiff has been, or likely will be, injured as a result of the false or misleading statement.”[145] These requirements mean that a plaintiff might not have a viable false advertising claim in a situation where they might have been able to sue for trademark infringement.

For example, although in the past Disney might have brought trademark claims against street vendors selling Mickey Mouse t-shirts,[146] under false advertising law, Disney might have difficulty showing that the deception had a material effect on consumers’ purchasing decisions and that Disney was injured as a result of one street vendor selling a few shirts.

Lastly, a false advertising claim requires actual advertising or promotion.[147] Simply selling a Mickey Mouse product without making a promotional claim about it would be insufficient to trigger liability. Consequently, although false advertising law might be a workable tool for Disney in a post-Dastar world, it would actually only be able to be employed in very limited circumstances.

D. Proposal #4: Creating stronger channeling doctrines and implementing election at the outset

Perhaps the best way to prevent overlapping protection is to minimize overlap at the outset. In fact, there are efforts to minimize this overlap built into both trademark and copyright laws called “channeling doctrines.” A channeling doctrine is a rule meant to police the boundaries of intellectual property and keep different works, so to speak, “in their lane.”[148] For example, there is a rule that short phrases and words (like “McDonald’s” or “Starbucks Coffee”) cannot be copyrighted while they may be trademarked. [149] Additionally, copyright has an originality requirement that trademark protection does not require.[150] As such, some logos, which do not contain the requisite amount of originality, cannot claim copyright protection even though they would be able to get trademark protection. For example, Tommy Hilfiger submitted its logo for copyright registration but was rejected for not having enough originality.[151] As such, this logo could be trademarked but not copyrighted.[152] But, that would not apply to a more original logo like Mickey Mouse. It is clear that, despite the existence of these rules, clearly the current channeling doctrines have been insufficient in preventing overlapping protection.

If Congress were to create stronger channeling doctrines, this might help to minimize overlap. For instance, if Congress were to decide that one could not copyright logos or that characters could not be used as part of a trademark, this might minimize overlap going forward.

Alternatively, without reducing the overall number of compositions protected, the U.S. could return to a system of election, where applicants would have to choose at the outset whether to seek trademark or copyright protection on a work but could not pick both. Yet, practically speaking, this has its challenges. According to Professors Jeanne Fromer and Mark McKenna, “[a] number of considerations affect the viability and value of a doctrine of election, particularly the timing and form of election, creator choice, and the subject of election.”[153] One does not actually need to register a copyright prior to enforcement, and trademark registration is not actually necessary at all.[154] Furthermore, trademark rights do not kick in until there is “use in the marketplace and distinctiveness established” which would likely happen at a different time from copyright registration.[155] For these reasons, election would have to be seriously reconsidered and framed in a way that would overcome these difficulties.

Conclusion

Walt Disney was famous for saying, “I only hope that we never lose sight of one thing—that it was all started by a mouse.”[156] Whatever Congress or the Supreme Court decides, it seems like Mickey Mouse will once again be a trailblazer. In the meantime, courts will do their best to implement Dastar while the public benefits from the works entering the “new” public domain.

* J.D. Candidate, N.Y.U. School of Law, 2020. The author would like to thank Professor Barton Beebe and Professor Graeme Dinwoodie for their suggestions and feedback.

[1] Mickey Mouse: From Walt to the World, Walt Disney: The Walt Disney Family Museum, https://www.waltdisney.org/exhibitions/mickey-mouse-walt-world (last visited Jan. 23, 2020).

[2] Steamboat Willie, IMDB, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0019422/ (last visited Jan. 23, 2020).

[3] Mickey Cartoons, Disney Mickey Mouse, https://mickey.disney.com/mickey-cartoons (last visited Jan. 23, 2020).

[4] Movie Series, Disney Mickey Mouse, https://mickey.disney.com/movies-series (last visited Jan. 23, 2020).

[5] Mickey Mouse in Videogames, Fandom, https://disney.fandom.com/wiki/Mickey_Mouse_in_video_games (last visited Jan. 23, 2020).

[6] Heather Thomas, Where to Meet Mickey Mouse at Disney World (no more Talking Mickey), WDW Prep Sch. (Sep. 26, 2016), https://wdwprepschool.com/where-to-meet-mickey-mouse-at-disney-world/.

[7] Mickey Mouse, Shop Disney, https://www.shopdisney.com/characters/mickey-mouse (last visited Jan. 23, 2020).

[8] Brooks Barnes, Disney Turns 90, and the Disney Marketing Machine Celebrates, N.Y. Times (Nov. 2, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/02/business/media/mickey-mouse-anniversary-90th.html.

[9] See Joseph P. Liu, The New Public Domain, 2013 U. Ill. L. Rev. 1395, 1440-41 (2013) (explaining that January 1, 2024 marks the loss of protection of the version of Mickey Mouse presented in Steamboat Willie. Future iterations of Mickey Mouse created since Steamboat Willie, for example, those featuring Mickey Mouse wearing white gloves or Mickey Mouse in color, are considered derivative works and are granted their own copyrights. These future iterations are protected until their copyrights expire.).

[10] Cory Doctorow, We’ll Probably Never Free Mickey, But That’s Beside the Point, Elec. Frontier Found. (Jan. 19, 2016), https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2016/01/well-probably-never-free-mickey-thats-beside-point.

[11] Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., 539 U.S. 23 (2003).

[12] Id. at 34 (“[A]llowing a cause of action under § 43(a) for that representation would create a species of mutant copyright law that limits the public’s federal right to copy and to use, expired copyrights.” (internal quotations omitted)).

[13] See Viva R. Moffat, Mutant Copyrights and Backdoor Patents: The Problem of Overlapping Intellectual Property Protection, 19 Berkeley Tech. L.J. 1474, 1476 (2004).

[14] Dianne Pham, New Year’s Eve in Numbers: Fun Facts About the Times Square Ball Drop, 6sqft (Dec. 27, 2018), https://www.6sqft.com/new-years-eve-in-numbers-fun-facts-about-the-times-square-ball-drop/.

[15] See generally Timothy B. Lee, Sorry Disney —Mickey Mouse Will Be Public Domain Soon—Here’s What That Means, Ars Technica (Jan. 1, 2019, 12:10 PM), https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2019/01/a-whole-years-worth-of-works-just-fell-into-the-public-domain/.

[16] Moffat, supra note 13, at 1478-82.

[17] U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl 8.

[18] Moffat, supra note 13, at 1478-88.

[19] Leslie A. Kurtz, The Methuselah Factor: When Characters Outlive Their Copyrights, 11 U. Miami Ent. & Sports L. Rev. 437, 439-40 (1994) (“Copyright strikes a balance between providing incentives to create and protecting the public domain from being stripped of the raw materials needed for new creations.”).

[20] See id.

[21] Moffat, supra note 13, at 1491.

[22] Act of May 31, 1790 ch. 15, 1 Stat. 124 (Copyright Act of 1790, current version at 17 U.S.C. § 102 (2018)).

[23] 17 U.S.C. § 102 (2018).

[24] See Kurtz, supra note 19, at 438-39 (explaining that in determining whether a character merits protection, courts look to whether the character is sufficiently distinctive or well-developed); see also DC Comics v. Towle, 802 F.3d 1012, 1021 (9th Cir. 2015) (setting forth a “three-part test for determining whether a character in a comic book, television program, or motion picture is entitled to copyright protection. First, the character must generally have ‘physical as well as conceptual qualities.’ . . . Second, the character must be ‘sufficiently delineated’ to be recognizable as the same character whenever it appears. . . . Third, the character must be ‘especially distinctive’ and ‘contain some unique elements of expression.’ . . . It cannot be a stock character.”). But see Kurtz, supra note 19, at 438-39 (“Courts have found less difficulty in protecting characters with a visual component, such as cartoons, than in protecting literary characters, which exist as more abstract mental images.”). See generally Warner Bros. Pictures v. Columbia Broad. Sys., 216 F.2d 945, 950 (9th Cir. 1954) cert. denied, 348 U.S. 971 (1955) (finding that a character is protected if it “constitutes the story being told”).

[25] See Moffat, supra note 13, at 1491.

[26] 17 U.S.C. § 102 (2018).

[27] Moffat, supra note 13, at 1491; see 17 U.S.C. § 302 (2018). But see 17 U.S.C. §§ 410-12 (2018) (explaining that while registration is not required, there are some benefits to registration such as: creating a presumption of ownership, allowing the copyright holder to file an infringement lawsuit and enabling the copyright holder to be eligible for certain damages and remedies in a copyright lawsuit).

[28] 17 U.S.C. § 302 (2018) (in the case of a work made for hire, including many corporate creative works, protection lasts “95 years from the year of its first publication, or a term of 120 years from the year of its creation, whichever expires first”).

[29] Act of May 31, 1790, ch. 15, 1 Stat. 124 (Copyright Act of 1790, current version at 17 U.S.C. § 102 (2018)).

[30] 17 U.S.C. § 24 (1909) (current version at 17 U.S.C. § 302 (2018)) (setting the term of protection at 28 years, renewable for another 28 years, resulting in a maximum of 56 years).

[31] 17 U.S.C. § 302 (2018).

[32] See generally Lawrence Lessig, Copyright’s First Amendment, 48 UCLA L. Rev. 1057, 1065 (2001) (referring to the CTEA as the Mickey Mouse Protection Act).

[33] 17 U.S.C. § 302 (2018); see also Eldred v. Ashcroft, 537 U.S. 186 (2003) (upholding the constitutionality of the CTEA).

[34] See Timothy B. Lee, Free Mickey—Why Mickey Mouse’s 1998 Copyright Extension Probably Won’t Happen Again, Ars Technica (Jan. 1, 2018, 8:00 AM), https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2018/01/hollywood-says-its-not-planning-another-copyright-extension-push/ (discussing some of the changes in politics, lobbying efforts, and the rise of internet companies which oppose strong copyright over the past 20 years).

[35] The Ten Commandments (Paramount Pictures 1923).

[36] The Pilgrim (Associated First National Pictures 1923).

[37] Edgar Rice Burroughs, Tarzan and the Golden Lion (A. C. McClurg, 1923).

[38] See January 1, 2019 Is (Finally) Public Domain Day: Works From 1923 Are Open To All!, Duke L. Sch. Ctr. for the Study of the Pub. Domain, https://law.duke.edu/cspd/publicdomainday/2019/ (last visited Jan. 23, 2020) (featuring a list of works entering the public domain in 2019 and a comparison of works that would have entered the public domain in 2019 if not for the CTEA).

[39] See Lee, supra note 15 (discussing other works that will fall into the public domain in the next few years, including George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, and Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises. Additionally, the copyrights to Superman, Batman, Disney’s Snow White, and early Looney Tunes characters will all fall into the public domain between 2031 and 2035.).

[40] Steamboat Willie was published in 1928 and granted a 28-year term copyright under the 1909 Copyright Act (renewable for an additional 28 years). Disney renewed, and therefore the copyright would have expired in 1984 (1928+28+28). However, when the Copyright Act of 1976 was passed, it tacked on 19 additional years of protection for works published before 1978, to bring duration for pre-1976 Act works into line with those under the 1976 Act. 17 U.S.C. § 304 (2012). Then, under the CTEA, an additional 20 years were added, bringing Steamboat Willie Mickey Mouse’s expiration date to December 31, 2023 (1984+19+20). Thus, Mickey Mouse will enter the public domain on January 1, 2024. But see Douglas A. Hedenkamp, Free Mickey Mouse: Copyright Notice, Derivative Works and the Copyright Act of 1909, 2 Va. Sports & Ent. L.J. 254, 255 (2003) (arguing that, technically, Mickey Mouse should already be in the public domain because Disney did not follow the proper formalities in registering Mickey Mouse under the 1909 Copyright Act).

[41] Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (Walt Disney Animation Studios 1937).

[42] Pinocchio (Walt Disney Animation Studios 1940).

[43] Fantasia (Walt Disney Animation Studios 1940).

[44] Dumbo (Walt Disney Animation Studios 1941).

[45] Bambi (Walt Disney Animation Studios 1942).

[46] Cinderella (Walt Disney Animation Studios 1950).

[47] Doctorow, supra note 10.

[48] Liu, supra note 9, at 1397.

[49] Id.

[50] Id. at 1397-98.

[51] Id.

[52] Id.

[53] A photo editing program.

[54] A music editing program.

[55] A movie editing program.

[56] Liu, supra note 9, at 1398.

[57] Id.

[58] See generally, Rebecca Tushnet, Registering Disagreement: Registration in Modern America Trademark Law, 130 Harv. L. Rev. 867 (2017) (discussing the importance of Federal registration in the trademark system and its status in the context of the common law protection of trademarks at both the Federal and state levels).

[59]See Barton Beebe, Trademark Law An Open Source Casebook 13 (2018) (ebook).

[60] Id. at 23.

[61] See 15 U.S.C. §§ 1052(e)(1), 1052(f) (2018).

[62] See 15 U.S.C. § 1052(e)(5) (2018).

[63] 15 U.S.C. § 1127 (2018); see also Beebe, supra note 59, at 30.

[64] See Beebe, supra note 59, at 30-33.

[65] APPLE, Registration No. 1,078,312; Beebe, supra note 59, at 30.

[66] The color(s) red is/are claimed as a feature of the mark. The mark consists of a red lacquered outsole on footwear that contrasts with the color of the adjoining (“upper”) portion of the shoe. The dotted lines are not part of the mark but are intended only to show placement of the mark, Registration No. 3,361,597; see also Christian Louboutin S.A. v. Yves Saint Laurent Am. Holding, Inc., 696 F.3d 206, 225 (2d Cir. 2012).

[67] The mark is a scent of a sweet, slightly musky, vanilla fragrance, with slight overtones of cherry, combined with the smell of a salted, wheat-based dough, Registration No. 5,467,089; see also Beebe, supra note 59, at 31.

[68] The mark consists of the sound of the famous Tarzan yell. The mark is a yell consisting of a series of approximately ten sounds, alternating between the chest and falsetto registers of the voice, as follow—1) a semi-long sound in the chest register, 2) a short sound up an interval of one octave plus a fifth from the preceding sound, 3) a short sound down a Major 3rd from the preceding sound, 4) a short sound up a Major 3rd from the preceding sound, 5) a long sound down one octave plus a Major 3rd from the preceding sound, 6) a short sound up one octave from the preceding sound, 7) a short sound up a Major 3rd from the preceding sound, 8) a short sound down a Major 3rd from the preceding sound, 9) a short sound up a Major 3rd from the preceding sound, 10) a long sound down an octave plus a fifth from the preceding sound, Registration No. 2,210,506; see also Beebe, supra note 59, at 31.

[69] The mark consists of the design and layout of a retail store. The store features a clear glass storefront surrounded by a paneled facade consisting of large, rectangular horizontal panels over the top of the glass front, and two narrower panels stacked on either side of the storefront. Within the store, rectangular recessed lighting units traverse the length of the store’s ceiling. There are cantilevered shelves below recessed display spaces along the side walls, and rectangular tables arranged in a line in the middle of the store parallel to the walls and extending from the storefront to the back of the store. There is multi-tiered shelving along the side walls, and a [sic] oblong table with stools located at the back of the store, set below video screens flush mounted on the back wall. The walls, floors, lighting, and other fixtures appear in dotted lines and are not claimed as individual features of the mark; however, the placement of the various items are considered to be part of the overall mark. Registration No. 4,277,914; see also Beebe, supra note 59, at 32-33.

[70] The mark consists of a three dimensional configuration of a version of the Coca Cola Contour Bottle, rendered as a two-liter bottle, having a distinctive curved shape with an inward curve or pinch in the bottom portion of the bottle and vertical flutes above and below a central flat panel portion. The matter shown in the mark with dotted lines is not a part of the mark and serves only to show the position or placement of the mark, Registration No. 4,242,307; see also Beebe, supra note 59, at 33.

[71] See 15 U.S.C. § 1057(c) (2018).

[72] Id.

[73] See 15 U.S.C. §§ 1065, 1115 (2018).

[74] See 15 U.S.C. § 1051(b) (2018).

[75] See 15 U.S.C. §§1125 (a), (c) (2018).

[76] Polaroid Corp. v. Polarad Elecs. Corp., 287 F.2d 492, 495 (2d Cir. 1961).

[77] Id.

[78] See Beebe, supra note 59, at 474.

[79] Louis Vuitton Malletier S.A. v. Haute Diggity Dog, LLC, 507 F.3d 252, 264-65 (4th Cir. 2007).

[80] MICKEY MOUSE, Registration No. 0,247,156.

[81] See Registration No. 5,027,809. Color is not claimed as a feature of the mark. The mark consists of a fanciful mouse.

[82] Registration No. 2,704,887.

[83] Color is not claimed as a feature of the mark, Registration No. 5,464,657.

[84] See Disney Enters. v. Away Disc., No. 07-1493 (DRD), 2010 WL 3372704, at *5 (D.P.R. Aug. 20, 2010).

[85] See Irene Calboli, Overlapping Copyright and Trademark Protection: A Call for Concern and Action, 2014 Ill. L. Rev. Slip Opinions 25, 29 (2014) (explaining that other characters such as the Simpsons, Angry Birds, Star Wars, the Lord of the Rings, the Hobbit, and other Disney characters are also protected simultaneously by both trademark and copyright).

[86] See Moffat, supra note 13, at 1496 (“This Article posits that overlapping protection has arisen mostly by accretion, as a result of the expansion of intellectual property rights, rather than by design.”).

[87] See Calboli, supra note 85, at 27-28.

[88] Feist Publ’ns, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340, 346 (1991).

[89] Beebe, supra note 59, at 38. (stating that “the term ‘fanciful,’ as a classifying concept, is usually applied to words invented solely for their use as trademarks”). Examples of fanciful marks include “Google” and “Acela.”

[90] Id. (“When the same legal consequences attach to a common word, i.e., when it is applied in an unfamiliar way, the use is called ‘arbitrary.’”). Examples of arbitrary marks include “Apple” for technology and “Camel” for cigarettes.

[91] Abercrombie & Fitch Co. v. Hunting World, Inc., 537 F.2d 4, 11 (2d Cir. 1976) (“A term is suggestive if it requires imagination, thought and perception to reach a conclusion as to the nature of goods.”). An example of a suggestive mark is “Lyft” for a ride sharing app.

[92] Abercrombie, 537 F.2d at 9.

[93] Id. at 11 (“A term is descriptive if it forthwith conveys an immediate idea of the ingredients, qualities or characteristics of the goods.”); for example, the mark “American Airlines” describes an airline that is American.

[94] Id. at 9 (“A generic term is one that refers, or has come to be understood as referring, to the genus of which the particular product is a species.”); see e.g., Beebe, supra note 59, at 36 (stating that the word “escalator” had become generic (citing Haughton Elevator Co. v. Seeberger, 85 U.S.P.Q. 80 (1950)).

[95] Calboli, supra note 85, at 27.

[96] See generally Barton Beebe & Jeanne C. Fromer, Are We Running Out of Trademarks? An Empirical Study of Trademark Depletion and Congestion, 131 Harv. L. Rev. 945, 947 (2018) (finding that evidence suggests that we are running out of trademarks which causes marketers to settle for second-best, less competitively effective marks).

[97] Calboli, supra note 85, at 27-28.

[98] See Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros., 529 U.S. 205, 208 (2000) (plaintiffs brought claims under copyright and trademark law for knock-off outfits sold by Wal-Mart).

[99] Frederick Warne & Co. v. Book Sales, Inc., 481 F. Supp. 1191, 1196 (S.D.N.Y. 1979).

[100] Id. at 1193-96.

[101] Id. at 1196.

[102] Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., 539 U.S. 23, 34 (2003).

[103] Id. at 25-27.

[104] Id. at 27.

[105] 15 U.S.C. § 1125 (2018).

[106] Dastar, 539 U.S. at 31-38.

[107] Id. at 34 (internal quotation marks omitted).

[108] Id.

[109] Steamboat Willie, Disney Video, https://video.disney.com/watch/steamboat-willie-4ea9de5180b375f7476ada2c (last visited Jan. 23, 2019).

[110] See, e.g., Mickey Mouse Knit Plush—Steamboat Willie, Shop Disney, https://www.shopdisney.com/mickey-mouse-knit-plush-steamboat-willie-15-400021021501.html (last visited Jan. 23, 2019) (featuring a plush Steamboat Willie doll that consumers can buy from the Disney online shop).

[111] See Steamboat Willie, Fandom, https://disney.fandom.com/wiki/Steamboat_Willie (last visited Jan. 23, 2019); see also Tormagainst, Aladdin and the King of Thieves—Mickey Mouse scene, Youtube.com, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KUoUsPkjie0 (last visited June 14, 2019).

[112] Steamboat Willie, supra note 109.

[113] Moffat, supra note 13, at 1507 n. 173.

[114] Id. at 1508 (“Disney used its copyright as leverage for getting trademark protection that it may not have been able to obtain without the benefits of copyright law.”).

[115] See, e.g., About the Quest for Hidden Mickeys, Find Mickeys, http://findmickeys.com/ (last visited Jan. 23, 2020) (explaining how Disney has hidden a number of hidden Mickey Mouse related images all around its theme parks and as Easter Eggs in its movies).

[116] See generally Joseph Greener, If You Give a Mouse a Trademark: Disney’s Monopoly on Trademarks in the Entertainment Industry, 15 Wake Forest J. of Bus. & Intell. Prop. L. 598 (2015) (providing examples of Disney’s efforts to protect its Mickey Mouse copyright and trademark including suing or threatening to sue daycares with drawings of Mickey Mouse on the walls, street vendors selling unauthorized t-shirts with images of Mickey and Minnie Mouse, a New York bar called “Mickey’s Mousetrap,” and deadmau5 (pronounced “dead mouse”), a Canadian DJ who is famous for wearing a mouse-shaped helmet during concerts).

[117] Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., 539 U.S. 23, 34 (2003).

[118] See Kurtz, supra note 19, at 443.

[119] Id. at 443.

[120] Id. at 443-44.

[121] Id. at 444.

[122] Id. at 445.

[123] Beebe, supra note 59, at 25.

[124] See Kurtz, supra note 19, at 441.

[125] Jessica Litman, Mickey Mouse Emeritus: Character Protection and the Public Domain, 11 U. Miami Ent. & Sports L. Rev. 429, 431 (1994).

[126] Mike Masnick, Sherlock Holmes and the Case of the Never Ending Copyright Dispute, Techdirt (May 26, 2015, 8:12 AM), https://www.techdirt.com/articles/20150524/17521431095/sherlock-holmes-case-never-ending-copyright-dispute.shtml.

[127] Klinger v. Conan Doyle Estate, Ltd., 988 F. Supp. 2d 879, 888 (N.D. Ill. 2013).

[128] Id. at 890.

[129] Id.

[130] See accompanying figure showing the progression of Mickey Mouse over time.

[131] Van Dyne-Crotty, Inc. v. Wear-Guard Corp., 926 F.2d 1156, 1159 (Fed. Cir. 1991) (citing Ilco Corp. v. Ideal Security Hardware Corp., 527 F.2d 1221, 1224 (C.C.P.A. 1976)); see generally Gideon Mark & Jacob Jacoby, Continuing Commercial Impression: Applications and Measurement, 10 Intell. Prop. L. Rev. 433 (2006).

[132] Hana Fin., Inc. v. Hana Bank, 135 S. Ct. 907, 910 (2015).

[133] Frederick Warne & Co. v. Book Sales, Inc., 481 F. Supp. 1191, 1196 (S.D.N.Y. 1979).

[134] See Jane C. Ginsburg, Intellectual Property as Seen by Barbie and Mickey: The Reciprocal Relationship of Copyright and Trademark Law, 65 J. of the Copyright Soc’y of the USA 1, 15-16 (2017).

[135] Id. at 15.

[136] Id. at 16.

[137] Id.

[138] See Kurtz, supra note 19, at 446.

[139] See id.

[140] See generally Mark McKenna, Dastar’s Next Stand, 19 J. Intell. Prop. L. 357 (2012) (discussing how best to interpret the Dastar opinion).

[141] Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., 539 U.S. 23, 38 (2003).

[142] See ZS Assocs. v. Synygy, Inc., No. 10-4274, 2011 WL 2038513, at *28 (E.D. Pa. May 23, 2011).

[143] 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a)(1)(B) (2018).

[144] ZS Assocs., 2011 WL 2038513, at *26.

[145] 44 Am. Jur. Proof of Facts 3d 1, § 1 (1997); see also Skil Corp. v. Rockwell Int’l Corp., 375 F. Supp. 777, 783 (N.D. Ill. 1974).

[146] See Greener, supra note 116, at 607.

[147] 44 Am. Jur. Proof of Facts 3d 1, § 1 (1997) (“The contested representations must be: (1) commercial speech, (2) made for the purpose of influencing consumers to buy defendant’s goods or services, and (3) disseminated sufficiently to the relevant purchasing public.”).

[148] See generally Mark P. McKenna, An Alternate Approach to Channeling? 51 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 873, 873-75 (2009).

[149] See Moffat, supra note 13, at 1505.

[150] See id. at 1505-06.

[151] See Review Board Letters Online, Tommy Hilfiger Flag, U.S. Copyright Off., https://www.copyright.gov/rulings-filings/review-board/docs/tommy-hilfiger-flag.pdf.

[152] See Moffat, supra note 13, at 1505-06.

[153] Jeanne C. Fromer & Mark P. McKenna, Claiming Design, 167 U. Pa. L. Rev. 123, 204-05 (2018).

[154] Id.

[155] Id.

[156] Kevin Fallon, Mickey Mouse is 90 and this Disney Exhibit Celebrates Him Perfectly, Daily Beast (Nov. 9, 2018, 4:38 AM), https://www.thedailybeast.com/mickey-mouse-is-90-and-this-disney-exhibit-celebrates-him-perfectly.