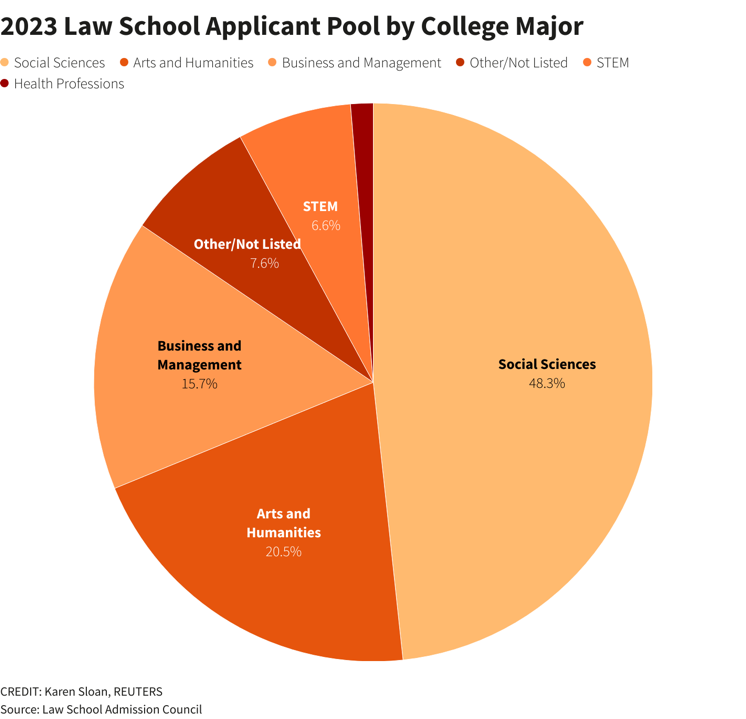

It’s no secret that lawyers are not scientists. The data is clear. An incredibly small portion of law school applicants, and later lawyers, have backgrounds in STEM. What follows is a judiciary unfamiliar with technical fields increasing in importance each day. The data is clear here as well. As science advances the technical judicial competency falls behind the prevailing methods, and courts will inevitably become less equipped to deal with scientific evidence. This article presents varying proposed solutions to the emerging issue of judicial technical ignorance.

The first solution, perhaps the one with the most potential, is to apply the concept of scientific peer-review to evaluate expert witness testimony. This solution, while not new, is promising. Peer review in the expert witness context would consist of a group of “peers” in the related field reviewing expert reports for scientific accuracy. Expert witness testimony and reports are the most prominent way to communicate scientific information to triers of fact. It is incredibly important to ensure expert witnesses are reliable. Peer review reduces the chance of mistakenly permitting unreliable expert witnesses. Dueling expert witnesses are a consistent evidentiary experience for lawyers and law students alike. Permitting peer review would confine dueling expert witnesses to technical areas of contested substance because peer review will filter out expert witnesses whose testimony supports misleading technical arguments. Removing improper expert testimony will lead to better outcomes when scientific evidence plays a significant role.

While the potential is significant, the downsides are debatably as impactful. The largest issue is a hampering of judicial efficiency. Peer review is a slow process with a paper requiring approximately three months to review. Even if we assume that time as one month per peer review of expert witness testimony, this adds a theoretical two months onto every case involving dueling expert witnesses. The overall strain of adding a significant amount of time to answer one factual question may simply not be worth the benefits conveyed. Further, concerns of bias and incentives within peer review are relevant. Scientists may have conflicts of interest or, more invidiously, a technical agenda they wish to impose. In terms of incentives, scientists peer reviewing experts have little to none. Scientific peer review is essentially crowd sourced with no payments to reviewing colleagues. Payment, theoretically, comes later via “speedy” review of the papers one publishes. In peer reviewing an expert witness, scientists receive no sort of reciprocal benefit to motivate efficient interaction. However, David Faigman suggests paying peer reviewers may address this issue.

Another interesting suggestion is the implementation of The Science Court. The proposal was looked into but was ultimately rejected. The focus of the institution was to resolve contested scientific issues, mainly for policy purposes. Although initially rejected, the idea of a science-focused court still holds a lot of promise. An important idea offered involved creating an appeals court with exclusive subject matter jurisdiction for technical issues within appellate litigation. When an issue arises that requires some sort of technical determination, the court steps in as an intermediary to solve the issue before kicking the case back to the regular circuit court. Alternatively, the court can retain appellate subject matter jurisdiction over the whole case. This conception would lessen the need to train judges in technical subjects.

The beauty of this solution lies not in the exclusive jurisdiction but in the fact that a court exists that can already step into this role, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. The Federal Circuit, of course, retains jurisdiction over all patent appeals. This exclusive subject matter jurisdiction certainly contributes to the makeup of the court, with 80% of the Federal Circuit judges having a STEM background. The Federal Circuit is formatted delicately to decide technical matters arising within litigation.

The last idea, what I call the “hotline” solution, involves forming an office serving a permanent and readily available technical advisory role to trial court judges throughout litigation. It all starts with a judge calling the “hotline.” Once called upon, the office has many possible roles. One is simply to provide technical summation and guidance, or at worst neutral experts who can provide these, to judges. Judges will then use their discretion to determine if they think further guidance is needed. However, the range of services to the judiciary does not need to be so laissez faire. Another potential function is to include the office in pre-trial correspondence and have them serve an advisory role throughout litigation. Effectiveness of the hotline could increase if judges individually solicit the types of scientific evidence litigators plan on presenting in pretrial conferences. The office can then tailor any technical advice or teachings to the specific needs of the litigation.

These proposed solutions cover only a few of those discussed in current literature but they all show promise. Instituting peer-review of expert witnesses produces methodological symmetry with technical subject matter. A technically focused appellate court creates a dependable backup to ensure questions will be answered correctly. An office to aid judges allows for better training and higher likelihood of successfully addressing technical issues at trial.